Chapter 7. Reform Movements from the 1870s to the 1980s

7.1 Introduction

There are many ways in which to contextualize reform historically. There are important economic and demographic contexts — such as booms and busts, or a surfeit or dearth of children or workers — and so one might be inclined to study reform as a response to those particular circumstances. While it is true that there are often identifiable catalysts to reform movements, it is also the case that most reform movements outlive their initial context and become much more: they become ways of viewing the world.

If this sounds vaguely religious, it should. Most movement cultures in Canada, over the last century or so, either had roots in denominational Christianity or were a reaction to the influence of organized religion. It seems safe to say that all were sustained over the longer term by a commitment to goals that were redemptive, a little millenarian, and sometimes purifying. All of the great reform movements of the post-Confederation era shared a few common catalysts and structural elements as well, not the least of which were a sense of pending disaster and a support base that was multi-provincial, if not national in its reach. There are exceptions but they are fewer than the commonalities.

These shared characteristics make it both possible and necessary to consider many of the reform movements side-by-side, regardless of their place on the nation’s timeline. There is spillover between them and the same faces show up in a variety of movements; there are also deep schisms between a few and, from time to time, unflinching hostility felt by participants in one movement to the champions of another. Social reform themes arise, in large measure, from a kind of deductive logic. There is poverty and therefore there must be causes of poverty; there is crime and fear and therefore there must be causes of disorder; there is inequity and unhappiness, danger and ugliness and all of these things must arise from some cause. The answers that social reformers offered up became banners — the other kind of cause —and thus rallying points for citizens from many backgrounds. This chapter begins with the 19th century’s great social movements, and concludes with the environmental movements of the 20th century.

Learning Objectives

- Identify the major reform movements of the post-Confederation era.

- Describe the common features, tactics, goals, and beliefs of the reform movements.

- Account for the popularity and longevity of specific reform movements.

- Detail the influence of the social gospel, temperance, and maternal feminist movements.

- Explain the rise of third parties as aspects of the reform movement.

- Assess the apparent distinctions between the first and second waves of feminism.

- Evaluate the extent to which late 20th-century movements like Greenpeace are part of a longer reform tradition.

Media Attributions

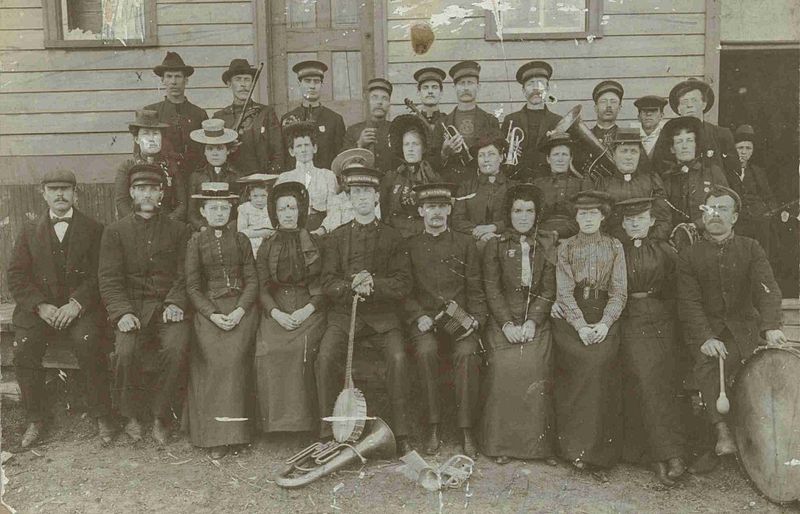

- Rat Portage Salvation Army Band, Ontario, 1898 is licensed under a Public Domain license