Chapter 4. Politics and Conflict in Victorian and Edwardian Canada

4.1 Introduction

Governing Canada presents rather distinctive, if not unique, challenges. Even when the Dominion consisted of just four provinces, there were substantial issues of distance and scale. The core of English-Canada’s population and its economic engine was in southwestern Ontario, a long way from Halifax. Railways and telegraphs closed that gap somewhat, but annexing the West and pulling BC into the Dominion just worsened matters exponentially. Distance might be compromised again with more rails and more roads but cultural issues are far less amenable to a technological fix. The idea of a federation — as opposed to a unitary state — stemmed principally from French-Canada’s long-standing, and entirely justified, fear of assimilationist anglophones and anti-Catholic Protestants. One very large part of the new nation, then, had signed on to a political unit that it inherently mistrusted. Could that mistrust be tempered by adopting a national policy of dualism? Would that just prove offensive to the English-Protestant majority? These issues could not be ignored: While the provinces might enjoy primacy in the area of culture and education, the federal government must somehow hold together the whole. These were issues that the countries against which Canadians were likely to measure themselves — the United States, Britain, Australia, and France — never had to deal. Twenty years after Confederation, its architect, John A. Macdonald, was not convinced that it was possible to sustain the federal union: “[I] have watched the cradle of Confederation & shouldn’t like to follow the hearse.”[1]

Which raises the question: What is the role of the federal regime? Constitutionally, its powers are limited but it does, from time to time, play a considerable and active role in many facets of Canadian life. Political history is about much more than constitutional history, but the constitution and the division of powers found therein are the ground rules for the Dominion’s governmental processes. As well, the British North America Act functioned in the first three decades of Confederation as a kind of strategic plan. It is highly unusual for a constitution to include provision for a railway; in the BNA Act it stands out like a contractual obligation, and this was a facet that was reinforced in BC’s Terms of Union in 1871. Likewise the BNA Act, and the debates that brought it together, made it clear that Canada was to be a mutual defence pact between a small group of colonies that were highly anxious about American appetites.

Measuring the performance of 19th century governments in particular thus means that we have to look at the tasks they were given and how they interpreted their responsibilities.

Learning Objectives

- Describe dualism and account for its fluctuating support.

- Explain the political successes of the Conservative Party from 1867 to the 1890s.

- Interpret the role played by the Catholic Church, and religion generally, in Canadian politics.

- Account for the rise to power of Wilfrid Laurier and the Liberal Party.

- Describe the crises faced by Laurier and how they illuminate Canadian political culture and society.

- Outline the principles of Canadian imperialism and nationalism, ca. 1900.

Long Descriptions

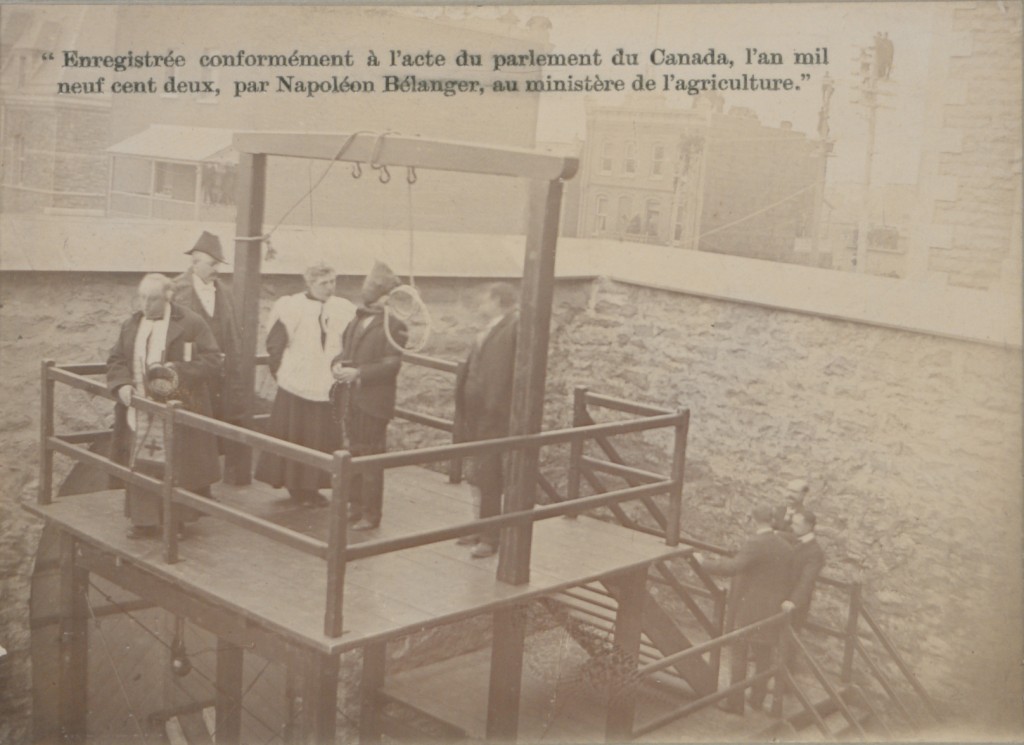

Figure 4.1 long description: A man has a rope around his neck and stands at the gallows, waiting to be hanged. He speaks to a priest. Another man looks over the railing around the gallows, speaking to an unseen audience. A few other men stand around the platform, and three stand on the set of stairs leading to the gallows. The caption reads “Enregistrée conformément à l’acte du parlement du Canada, l’an mil neuf cent deux, par Napoléon Bélanger, au ministère de l’agriculture.” Translated into English, this is “Registered in accordance with the Act of the Parliament of Canada, in the year one thousand nine hundred and two, by Napoléon Bélanger, to the Ministry of Agriculture.” [Return to Figure 4.1]

Media Attributions

- L’execution de Lacroix © Napoléon Bélanger is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Quoted in Ged Martin, John A. Macdonald: Canada's First Prime Minster (Toronto, ON: Dundurn, 2013), p.176. ↵

The idea that Canada could or should construct its culture and institutions around two cultures, French and English. In contrast with unification (which favours one culture) and pluralism or multiculturalism in which French in particular is at risk of becoming a minority culture.