Chapter 4. Politics and Conflict in Victorian and Edwardian Canada

4.7 Edwardian Crises

Transforming Canada

The Boer War crisis was acute and relatively brief. Other issues offered more ongoing and chronic discomfort, and the need for quite a lot of adjustment. The most dramatic of these is the accelerated rate of immigration under the Laurier regime and, specifically, under the guidance of his Minister of the Interior, Clifford Sifton (see Section 5.4). Between 1896-1911 the demographics of Canada changed spectacularly. There is irony in the fact that Laurier’s first days in office were spent addressing the demographic marginalization of Franco-Catholics in Manitoba: by 1911 the hundreds of thousands of Mennonites, Germans, Doukhobors, Americans, and others who poured into the Prairies would transform the region to such a point that some aspects of the Manitoba schools crisis would seem already remote.

The issue of how best to manage international commerce was another of Laurier’s ongoing concerns. It was largely resolved by introducing a preferential tariff that was meant to encourage other nations to bring down their own barriers. Insofar as it didn’t remove tariffs altogether the policy pleased manufacturers. Because it showed preference to Britain as a trade partner, it pleased imperialists. Without substantially addressing any of the agricultural community’s complaints, it left homesteaders and farmers feeling neglected and wondering if either of the two national parties would ever come around to their way of seeing things.

Timing, however, is everything. The world economy was, in 1896, entering into a recovery phase. As settlers poured into the West, demand for wheat and mineral products grew. Historians disagree as to whether the preferential tariff had a direct effect on the Canadian economy because it was introduced on a rising tide. As grain production and exports climbed rapidly, so too did manufacturing sales. There now emerged for the first time significant bottlenecks in the movement of goods. Perhaps carried away by the booming economy, Laurier in 1903 launched a campaign to build a new transcontinental railway that would serve neglected parts of the Maritimes, northern Ontario, the northern Prairies, and a Pacific outlet in the new port-city of Prince Rupert. This was taking a page from Macdonald’s playbook. The Canadian Northern (later called the Canadian National) Railway and the Grand Trunk Railway increased capacity and penetrated the northern West while a dense network of smaller lines and branch lines cross-hatched the face of the Prairies before 1914. There were at least 15,000 km of track running east and west and north and south in Canada. One government after the next subscribed to the view that railways were good politics: They created jobs and markets, stimulated industrial growth, and tied the whole together tighter and tighter.

Improved conditions after 1896 led to increased Canadian self-confidence. Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee was marked in London by an unprecedented meeting between colonial leaders and the British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain (1836-1914), whose goal it was to build an Imperial Federation. As was his tendency in the past, Laurier publicly espoused an intense loyalty to and affection for Britain, but at the meeting table he was unwilling to relinquish any Canadian sovereignty to a proposed British-led global federal system. Laurier knew, as no other leader around that table could have, the challenges of co-existence within a federal structure and, whatever his disagreements with Henri Bourassa, he was looking toward a day when Canada would be more and not less independent. After winning a second mandate in 1900, Laurier would similarly turn down British offers of an Imperial Council, an Imperial Navy, and an Imperial Commercial Union. As he explained to the House of Commons, the first loyalty of the Canadian government was to the Canadian peoples (however that might be defined), not to London.

The economy that had once been Laurier’s ally began to outrun him at the turn of the century. Urban growth created cities that the small-town lawyer did not understand, and an industrial working class that was still more alien to Laurier’s experiences. He kept one eye on an ultramontane clergy and the other shut tight against the new issues inherent in 20th century modernization. The creation of a new position – Deputy Minister of Labour – was a nod toward industrial issues, but the legislation that arose from it mostly kept the state on the margins of disputes and out of the way of expanding and monopolistic enterprises. These conditions, coupled to immigration and growth in the West, all conspired to change the electorate and to move the goalposts of Canadian politics. A compromise made in 1896 on behalf of 5 million Canadians might not have the same resonance in 1911 when there were 2 million more.

By 1909 Laurier’s health – never good – was increasingly a problem. The Liberals had now been in office for 13 years and had won four consecutive elections. Canada was vastly changed from what it had been when Laurier first came to office and the energy that Laurier and his original cabinet brought to the job was largely spent. One final major issue would finish off the government.

The Naval Crisis

The second great challenge of Laurier’s administrations echoed the first and picked up on a theme that dogged him from the start of his time as prime minister. After 40 years of relative autonomy from Britain, Canada’s military capacity was still seriously underdeveloped. Dependence on Britain to provide the necessary muscle now had to be reassessed. The British would have preferred a cheque from Canada to cover the cost of building additional Royal Navy vessels, but nationalist voices in the Dominion (including Laurier’s own) were more comfortable with the prospect of a Canadian Navy.

There was a need for some urgency on this issue: Germany was building up its navy (as was France and the United States) and Britain was anxious not to lose its advantage at sea. The Conservatives, under Robert Borden’s leadership, called for Ottawa to purchase a pair of Dreadnought-class battleships for the Royal Navy and to defer the issue of a Canadian Navy until the next election. How that scenario might have turned out would be difficult to guess because the naval issue had the potential to split the imperialists down the middle: some were Canadian nationalists in imperialist clothing while others were British imperialists first, last, and always. Laurier decided to press on and introduced the Naval Service Bill early in 1909, proposing to assemble a Canadian Navy that could be available on loan to Britain at the discretion of the Dominion Parliament. Consisting of six destroyers and five cruisers, it was instantly ridiculed as a “tinpot navy.” Caught once again between Anglo-Protestant imperialists on one side, who moaned it was not enough, and Franco-Catholics on the other side, who cried that it was too much, Laurier found there was little appetite in Canadian politics for his variety of compromise.

The last nail in Laurier’s political coffin was that old chestnut, reciprocity. A delegation to Washington, DC had finally managed to get American agreement on a deal that would provide free access to American markets for natural resources and agricultural products along with limited trade in manufactured goods. This should have satisfied farmers in the West and industrialists in the central and eastern provinces. It did not. Manufacturers and investors who had hitherto supported the Liberal Party turned on it, as did Clifford Sifton. Wounded on two fronts, Laurier was exhausted and called an election, which he lost.

Laurier’s Legacy

It is difficult to assess Laurier’s long record of compromise objectively. He kept the worst Canadian divisions under control, it is true, but many of his compromises either irritated underlying fault lines or they proved to be very poor deals indeed. The creation of the provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta in 1905 offers a case in point. The territorial administration under Premier Frederick Haultain had limited, sub-provincial powers, despite an elected assembly at Regina. Local politicians favoured the creation of a single new province that would stretch from (still undersized) Manitoba to the Rockies. Laurier preferred two provinces and sought to restore minority rights in the West in the form of publicly-funded separate schools. He would win on the provinces and their boundaries, but he lost badly on the schools issue. It cost him the support of Sifton, who was an unflinching supporter of the anglicization of the West, and Henri Bourassa, who resigned from the government years beforehand but had hitherto maintained a lukewarm relationship with Laurier. Now the prime minister found two of his nation’s most effective leaders attacking him at the same time for being simultaneously an ally and an enemy of French-Catholicism.

Many of Laurier’s tests ended the same way. Of course it is the business of opposition politicians to puncture the support of the government, so one can hardly blame figures like Charles Tupper and Robert Borden for finding fault with Laurier’s deals. Henri Bourassa’s role and Clifford Sifton’s: those are more complex. When Bourassa left Laurier’s cabinet over the matter of the Boer War, Laurier said to him, “I regret your going. We need a man like you at Ottawa, although I should not want two.”[1] Bourassa was uncompromising and tapped into Québecois fears of liberalism, modernity, and imperialism as he sniped at Laurier. At the same time, his articulation of a nationalist position was as erudite and gifted as anything coming out of the imperialist camp. Sifton’s role is harder to measure. There was none more entrepreneurial in the Laurier cabinet, nor was there anyone whose job (as Minister responsible for immigration) required that he think long and hard about the mixing of cultures. Sifton simply concluded early on that a Canada built on dualist principles was unsustainable and that the future belonged to English-Canadian virtues and habits.

It was “an unholy alliance” of imperialists and nationalists that laid Laurier low in 1911. His career was marked by conflict with the conservative, ultramontane Catholic clergy in Quebec, and he spoke so often about his fear of religious strife in Canada that one cannot but conclude that he genuinely believed it was possible. More than that, he believed that being in office meant doing good. “When I am premier,” he said in 1890, “you won’t have to look up figures [statistics] to find out whether you are prosperous: you will know by feeling in your pockets.”[2] He attacked Macdonald in 1886 for his actions with regard to the Northwest, saying “What is hateful…is not rebellion but the despotism which induces the rebellion; what is hateful are not rebels but the men, who, having the enjoyment of power, do not discharge the duties of power; they are the men who, having the power to redress wrongs, refuse to listen to the petitioners that are sent to them; they are the men who, when asked for a loaf, give a stone.”[3] This was a leader who listened to all sides, perhaps too much.

Key Points

- The 20th century opened with a suite of political and social crises in Canada.

- Continuing immigration from east and central Europe was transforming the population.

- Massive new railway construction projects stimulated the economy and tightened Canada’s grip over the West and BC.

- The Naval Service Bill divided Canadians between those who sought to serve Britain and the Empire first, and those who saw a Dominion fleet as an important step toward independence.

Long Descriptions

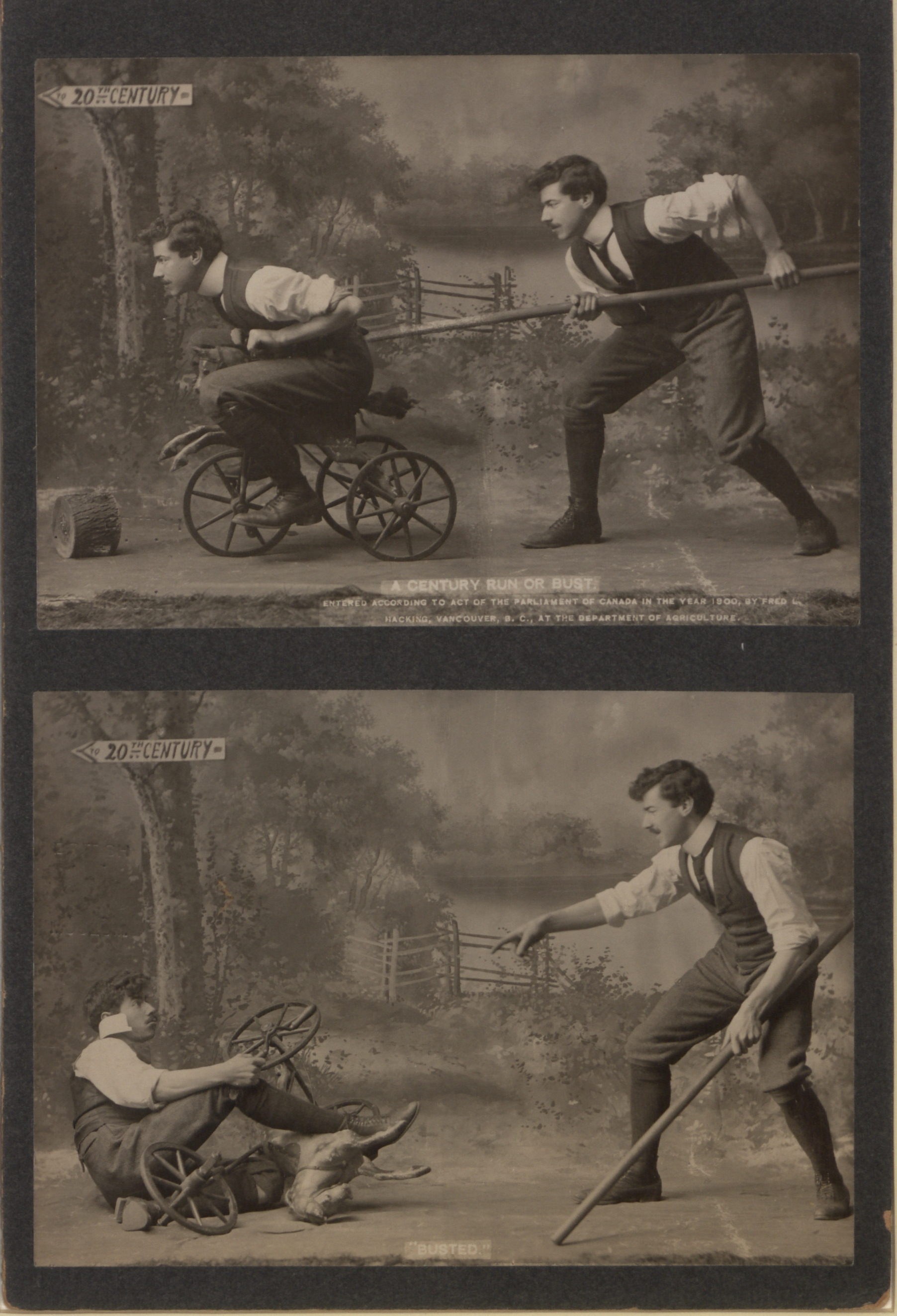

Figure 4.18 long description: A set of two photographs from the year 1900, marking the commencement of the 20th century. The first, entitled “A century run or bust”, shows a man riding a child’s tricyle, being pushed with a stick by another man, towards the direction marked as the “20th Century” by a sign on a nearby tree. The second photograph, entitled “Busted”, shows the man falling off, and destroying, the tricycle, and being mocked by the second man. [Return to Figure 4.18]

Media Attributions

- A century run or bust / Busted © Fred L. Hacking is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Frank Swannell at Takla Lake © Frank Swannell is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Sir Wilfrid Laurier at New Westminster, B.C. © William T. Cooksley is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Quoted in J. Schull, Laurier: The First Canadian (Toronto: MacMillan, 1965) 459. ↵

- Quoted in O.D. Skelton, The Day of Sir Wilfrid Laurier: A Chronicle of Our Own Time (Toronto: Glasgow, Brook & Company, 1916): 327. ↵

- Canada, Official Report of the Debates of the House of Commons of the Dominion of Canada, 1886, vol. XXI (Ottawa: Queen's Printer 1886): 179. ↵

Charges (a tax) added to imported goods so as to make their sale price higher than domestic goods and, thus, make domestic goods more competitive; some trade partners are less discriminated (they are “preferred”) over others.