Pain and Mobility

10.4 Clinical Reasoning and Decision-Making for Pain and Mobility

Clinical reasoning is a way that nurses think and process our knowledge, including what we have read or learned in the past, and apply it to the current practice context of what we are seeing right now. [1] Nurses make decisions all the time but making decisions requires a complex thinking process. There are many tools that are useful and found online that can support your thinking through to clinical judgments. This book uses the nursing process and clinical judgment language to help you understand the application of medication to your clinical practice.

After reviewing basic concepts related to pain and several disorders requiring analgesic or musculoskeletal medication, it is time to consider how to make decisions about these types of medications.

Assessment

Although there are numerous details to consider when administering medications, it is always important to first think about what you are giving and why.

First, let’s think of why? Recognizing Cues

Prior to administration of any medication, nurses should perform an assessment and gather cues to analyze and prioritize a hypothesis.[2]

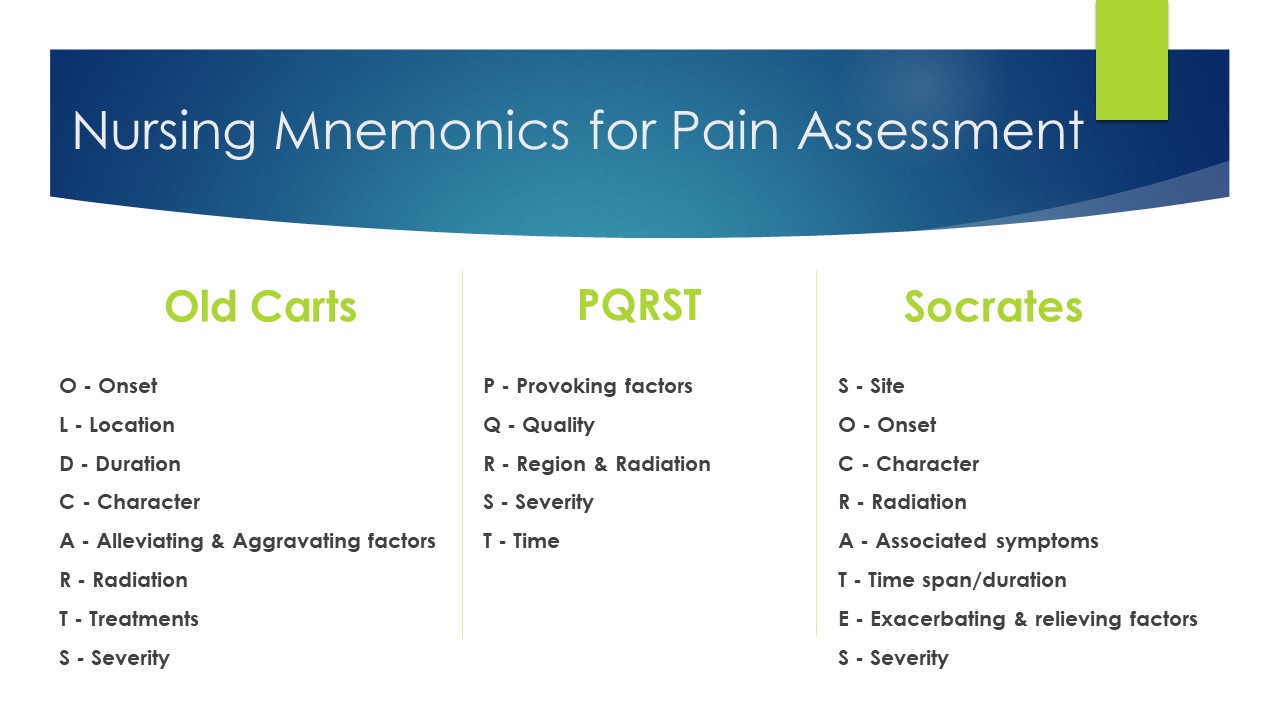

For instance, if considering a pain medication, you will want to complete a full pain assessment such as determining a pain scale and acceptable pain level for your client. See Figure 10.4a[3] for common nursing mnemonics for pain assessment.

If administering a medication related to mobility or the musculoskeletal system, you will first want to collect data such as strength and stability.https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingskills/chapter/13-4-musculoskeletal-assessment/

Additional baseline information to collect prior to administration of any analgesic or musculoskeletal medication includes any history of allergy or a previous adverse response.

Lifespan Considerations

A majority of medications are calculated specifically based on the client’s size, weight, and renal function. Client age and size are especially vital in pediatric clients. A child’s stage of development and the size of their internal organs will greatly impact how the body absorbs, digests, metabolizes and eliminates medications.

Visual pain scales have been developed as a tool of communication about pain with children through clients at end of life. See Figure 10.4b for the FACES Pain Rating Scale.[4] To use this scale, use the following evidence-based instructions.

- Explain to the client that each face represents a person who has no pain (hurt), some, or a lot of pain.

- Explain, “Face 0 doesn’t hurt at all. Face 2 hurts just a little. Face 4 hurts a little more. Face 6 hurts even more. Face 8 hurts a whole lot. Face 10 hurts as much as you can imagine, although you don’t have to be crying to have this worst pain.”

- Ask the client to choose the face that best represents the pain they are feeling.

![Wong-Baker FACES Foundation (2020). Wong-Baker FACES® Pain Rating Scale. Retrieved [Date] with permission from http://www.WongBakerFACES.org A pain scale from 0 to 10 that uses a combination of cartoon faces and words to convey the severity of the pain.](https://opentextbc.ca/accessibilitytoolkit/wp-content/uploads/sites/397/2022/05/image6-4.png)

Determinants of Health and Cultural Safety

There are several considerations for nurses when working with clients who have conditions related to pain and mobility. It is important that you engage in client care that is culturally safe, remember that pain is what the client says it is, and not further marginalize clients.[5]

Interventions

Next, plan (refine your hypothesis), and take action.

Once you have gathered your assessment data and cues, you’ll begin to generate solutions to the concern that your client has. Prior to administration, it is important to consider the best route of administration for this client at this particular time. For example, if the client is nauseated and vomiting, then an oral route may not be effective.

There are also legal and ethical considerations when administering some analgesics such as opioids. When administering opioid medications, it is important to remember that these medications are controlled substances with special regulations regarding storage, auditing counts, and disposal or wasting of medication. Read more information about controlled substances in Chapter 2.2 Ethical and Professional Foundations.

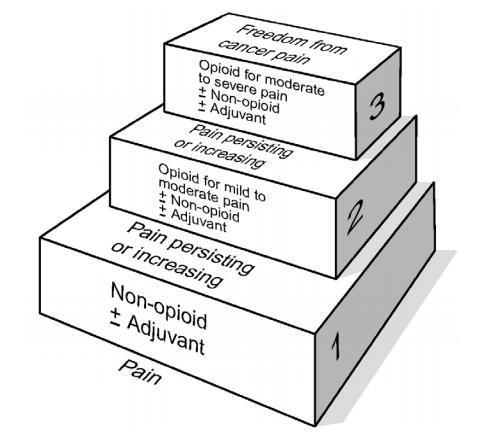

A general rule of thumb when administering analgesics is to use the least invasive medication that is anticipated to treat the level of pain reported by the client. The World Health Organization (WHO) pain ladder was originally developed for the selection of analgesics for clients with cancer but illustrates the concept that pain control should be based on the level indicated by the client. See Figure 10.4c[6] for an image of the WHO ladder. For example, if a client reports a pain level of “2,” then it is appropriate to start at the lowest rung of the ladder and administer a non-opioid. However, it may be clinically indicated to start at “Level 3” on the WHO ladder for clients who present with severe, difficult pain.

It is important to anticipate any common side effects and the expected outcome of the medication, as well as considerations regarding what to teach the client and their family regarding the medications. This information will be dependent upon the medication.

Evaluation

Finally, evaluate the outcomes of your action.

It is important to always evaluate the client’s response to a medication. In most circumstances, the nurse should assess for a decrease in pain 30 minutes after intravenous (IV) administration and 60 minutes after oral medication. If the client’s pain level is not acceptable, the nurse should investigate alternate treatment modalities. These modalities may include, but are not limited to aromatherapy, repositioning the client, hot or cold treatments, and listening to music.

As the nurse is the client’s advocate, the healthcare provider may have to be informed if the client’s pain is not being controlled by analgesics. Nurses should also evaluate for any adverse effects. For instance, one adverse effect of opioid analgesics is respiratory depression. The nurse should evaluate the respiratory rate and pulse oximetry after administration of the medication. The nurse may need to consider administering other medications that treat the side effects of analgesic medication.

Image Descriptions

Figure 10.4a Nursing Mnemonics for Pain Assessment – Image Description

- Old Carts

- O – Onset

- L – Location

- D – Duration

- C – Character

- A – Alleviating & Aggravating factors

- R – Radiation

- T – Treatments

- S – Severity

- PQRST

- P – Provoking factors

- Q – Quality

- R – Region & Radiation

- S – Severity

- T – Time

- Socrates

- S – Site

- O – Onset

- C- Character

- R- Radiation

- A – Associated symptoms

- T – Time span/duration

- E – Exacerbating & relieving factors

- S – Severity

Figure 10.4c The WHO Pain Ladder – Image Description

A diagram of three steps. The horizontal part of the step is labelled with the level of pain and the vertical part of the step is labelled with the options for pain management. The top step is labelled “Freedom from cancer pain”:

- Pain: Non-opiod ± Adjuvant

- Pain persisting or increasing: Opioid for mild to moderate pain. ± Non-opioid, ± Adjuvant.

- Pain persisting or increasing: Opiod for moderate to severe pain. ± Non-opioid, ± Adjuvant.

- NCSBN. (n.d). NCSBN Clinical Judgement Measurement model. https://www.ncsbn.org/14798.htm ↵

- Tanner, C. (2006). Thinking like a nurse: A research-based Model of Clinical Judgement. Journal of Nursing Education 45(6). https://www.mccc.edu/nursing/documents/Thinking_Like_A_Nurse_Tanner.pdf ↵

- "Mnemonics for Pain Assessment" by Julie Teeter is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Used with permission from http://www.WongBakerFACES.org. ↵

- Craig, K., Holmesm, C., Hudspith, M., Moor, G., Moosa-Mitha, M., Varcoe, C. & Wallace, B. (2020). Pain in persons who are marginalized by social conditions. Pain, 161(2). doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001719 ↵

- World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief. 2nd ed. Geneva: WHO; 1996. ↵

A way that we think and process our knowledge including what we have read or learned in the past and apply it to the current practice context of what we are seeing right now.