Gastrointestinal Elimination

7.2 Gastrointestinal Elimination Concepts

Amanda Egert; Kimberly Lee; and Manu Gill

Concepts Related to Gastrointestinal Elimination

This resource provides a basic introduction to the concept of gastrointestinal elimination as it relates to pharmacology. The concept of gastro-intestinal elimination is defined as “the excretion of waste products”[1] specifically through the gastrointestinal system. This chapter also discusses nausea and vomiting, which are also connected to the gastrointestinal system.

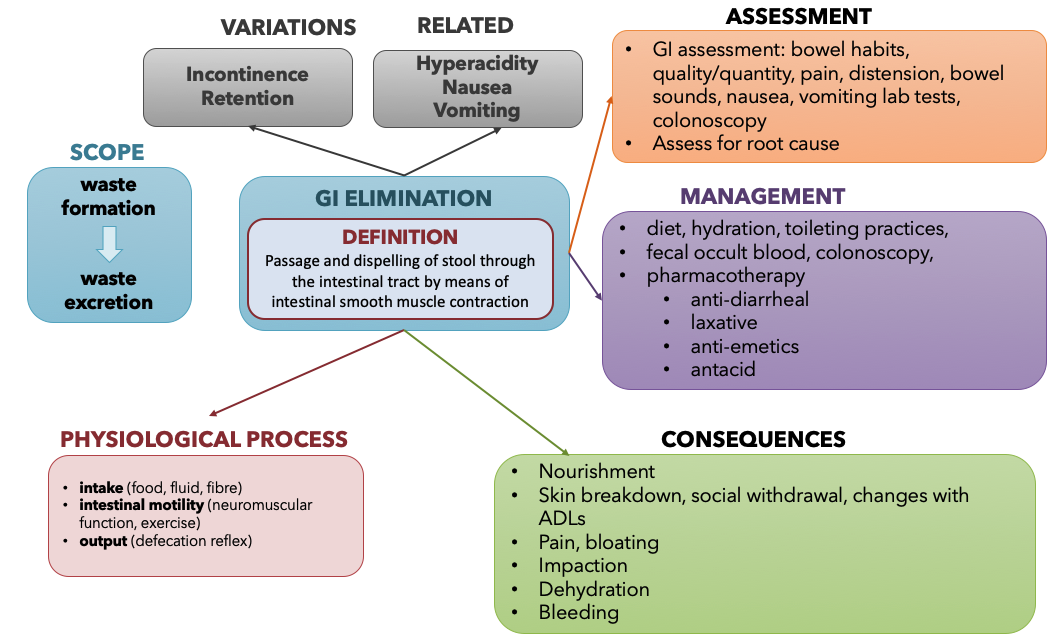

The example concept map below in figure 7.2a provides a summary of the key information necessary to understand gastrointestinal elimination informed by several resources.[2]

You are encouraged to revisit this map after you have completed the chapter.

Overview of Gastrointestinal System and Processes

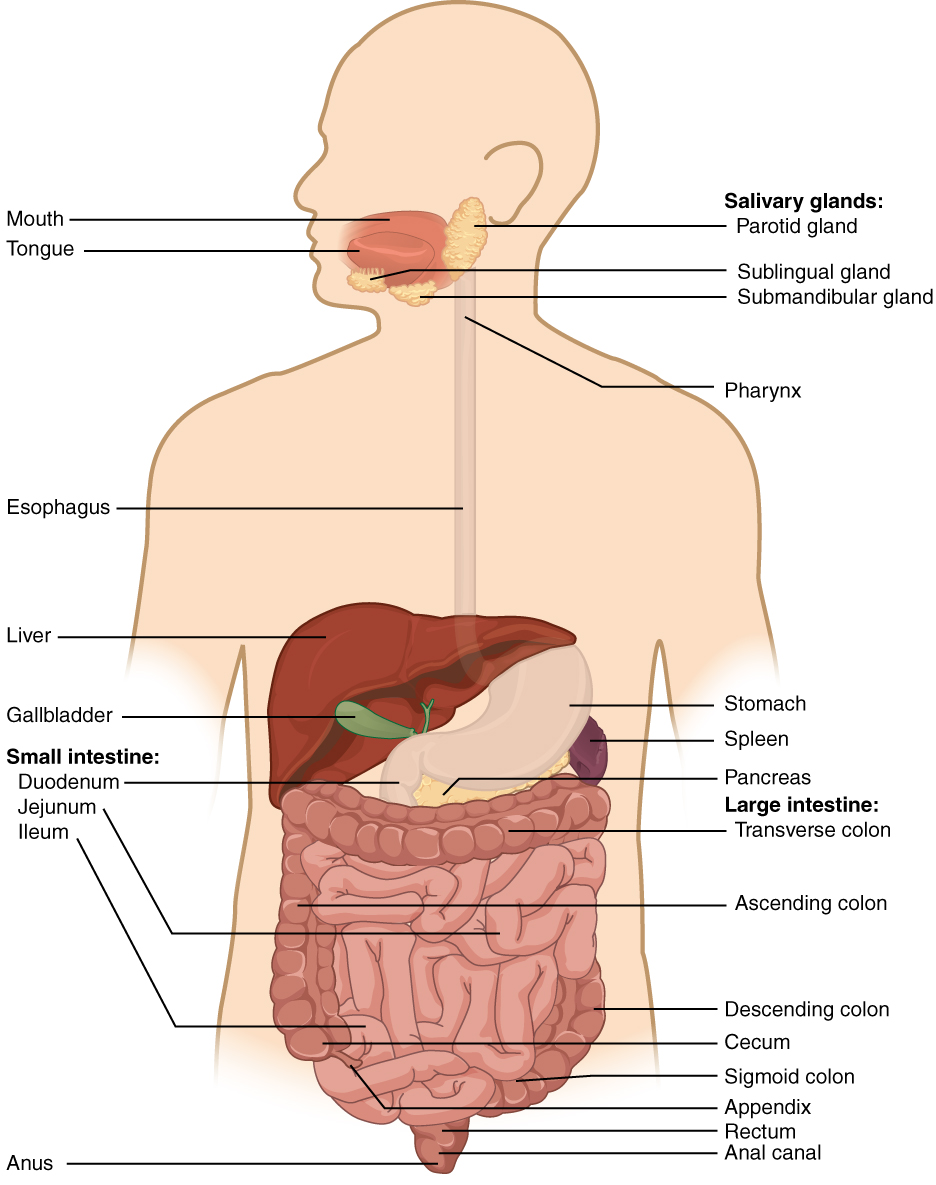

It is important to understand GI anatomy and physiology information in order to understand how GI medications work. Figure 7.2b[3] illustrates the anatomical components of the gastrointestinal system as a whole. The remainder of this section will provide a review of the digestive system, digestive system processes and regulation, the stomach, the small and large intestines, and chemical digestion and absorption. Medications related to hyperacidity, bowel disorders, and nausea and vomiting will be discussed later in the chapter, with reference to how they target pathophysiological concepts related to these organs and processes.

Watch the videos below for a review of the gastrointestinal system and digestive system.

Gastrointestinal System Review[4]

Ted Ed Review of The Digestive System[5]

The Stomach and Digestion

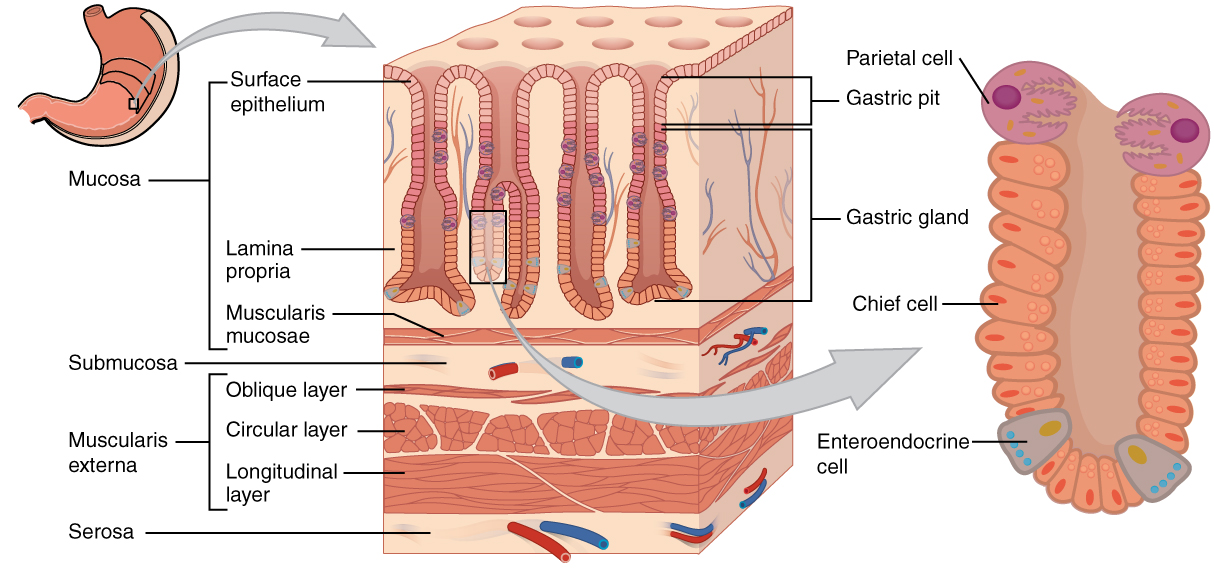

The stomach contains cells that secrete different substances as part of the digestive process: parietal cells, chief cells, and surface epithelium cells. See an image of the stomach and these cells in Figure 7.2c.[7]

Surface epithelium cells are found within the lining of the stomach and secrete mucus as a protective coating. Parietal cells and chief cells are found within the gastric glands. Parietal cells produce and secrete hydrochloric acid (HCl) to maintain the acidity of the environment of a pH of 1 to 4. Parietal cells also secrete a substance called intrinsic factor, which is necessary for the absorption of vitamin B12 in the small intestine. Parietal cells are the primary site of action for many drugs that treat acid-related disorders. Chief cells secrete pepsinogen that becomes pepsin, a digestive enzyme, when exposed to acid. The stomach also contains enteroendocrine cells (ECL or enterochromaffin-like cells) located in the gastric glands that secrete substances including serotonin, histamine, and somatostatin. G cells in the stomach secrete gastrin that promotes secretions of digestive substances. Although these cells play an important role in the digestive system, acid-related diseases can occur when there is an imbalance of secretions.

Elimination and Defecation

The digestive system is continually at work, but unless something goes amiss, you don’t notice your digestive system working. The final step of digestion is called defecation, when undigested materials are removed from the body as feces. During this final step, the large intestine absorbs water and changes the waste from a liquid into stool; then peristalsis helps move the stool into the rectum. Diarrhea and constipation occur when conditions occur that affect this final step of defection.

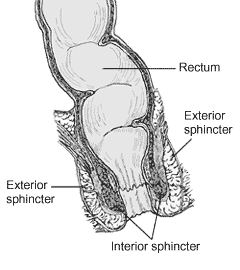

The process of defecation begins when mass movements force feces from the colon into the rectum, stretching the rectal wall and provoking the defecation reflex, which eliminates feces from the rectum. This parasympathetic reflex is mediated by the spinal cord. It contracts the sigmoid colon and rectum, relaxes the internal anal sphincter, and initially contracts the external anal sphincter. Figure 7.2d[8] reviews the anatomy of the rectum and its external and internal sphincters. The presence of feces in the anal canal sends a signal to the brain, which gives the person the choice of voluntarily opening the external anal sphincter (defecating) or keeping it temporarily closed. If defecation is delayed until a more convenient time, it takes a few seconds for the reflex contractions to stop and the rectal walls to relax. The next mass movement will trigger additional defecation reflexes until defecation occurs.[9]

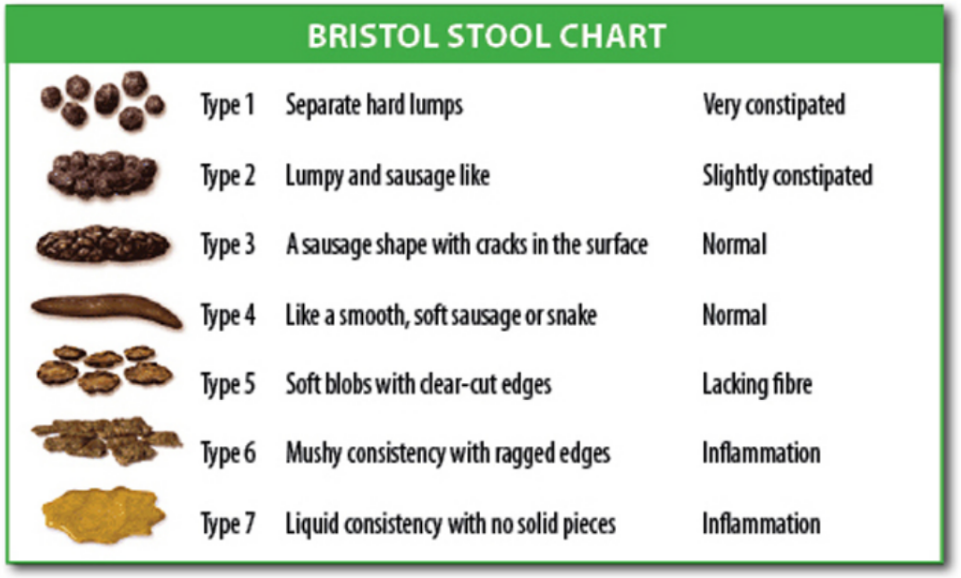

If defecation is delayed for an extended time, additional water is absorbed, making the feces firmer and potentially leading to constipation. Alternatively, if the waste matter moves too quickly through the intestines, not enough water is absorbed and diarrhea can result. Figure 7.2e[10] demonstrates the Bristol Stool Chart that is used to assess stool characteristics ranging from very constipated to diarrhea.

You can further review how the digestive system works at the following links:

- Your Digestive System and How it Works[11]

- Video on Digesting Food [12]

- Overview of the Digestive System [13]

- Digestive System Processes and Regulation[14]

- The Stomach[15]

- The Small and Large Intestines[16]

- Chemical Digestion and Absorption: A Closer Look[17]

Image Description

Figure 7.2a GI Elimination Concept Map image description: This is a concept map that shows the components of the GI elimination. It starts with the definition for GI elimination: the passage and dispelling of stool through the intestinal tract by means of intestinal smooth muscle contraction.

Variations

- Incontinence

- Retention

Related

- Hyperacidity

- Nausea

- Vomiting

Assessment

- GI assessment: bowel habits, quality/quantity, pain, distension, bowel sounds, nausea, vomiting lab tests, colonoscopy

- Assess for root cause

Management

- diet, hydration, toileting practices,

- fecal occult blood, colonoscopy,

- pharmacotherapy

- anti-diarrheal

- laxative

- anti-emetics

- antacid

Consequences

- Nourishment

- Skin breakdown, social withdrawal, changes with ADLs

- Pain, bloating

- Impaction

- Dehydration

- Bleeding

Physiological Process

- intake (food, fluid, fibre)

- intestinal motility (neuromuscular function, exercise)

- output (defecation reflex)

Scope

- Waste formation leads to waste excretion [Return to Figure 7.2a]

Figure 7.2e image description: Bristol Stool Chart is used to assess stool characteristics ranging from very constipated to diarrhea.

| Type | Descriptions | Condition |

|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | Separate hard lumps | Very constipated |

| Type 2 | Lumpy and sausage-like | Slightly constipated |

| Type 3 | A sausage shape with cracks in the surface | Normal |

| Type 4 | Like a smooth, soft sausage or snake | Normal |

| Type 5 | Soft blobs with clear-cut edges | Lacking fibre |

| Type 6 | Mushy consistency with ragged edges | Inflammation |

| Type 7 | Liquid consistency with no solid pieces | Inflammation |

- Jean Giddens, Concepts of Nursing Practice – 2nd edition (Missouri: Elsevier, 2017), page 138 ↵

- Jean Giddens, Concepts of Nursing Practice – 2nd edition (Missouri: Elsevier, 2017) ↵

- "Components of the Digestive System" by CNX OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0 Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/23-1-overview-of-the-digestive-system ↵

- Forciea, B. ( 2015, March 18). Anatomy and Physiology of the Digestive System [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Video used with permission. https://youtu.be/1ssJV-EpfiQ. ↵

- Bryce, E. (2017, December 14). How Your Digestive System Works. [YouTube]. https://youtu.be/Og5xAdC8EUI. ↵

- Meet the Gastrointestinal Tract! by Raja Narayan is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 ↵

- "2415 Histology of StomachN.jpg" by CNX OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 Access for free at https://cnx.org/contents/FPtK1zmh@16.7:O9dvCxUQ@8/23-4-The-Stomach ↵

- "Anorectum.gif" by U.S. Government National Institutes of Health is licensed under CC0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- "BristolStoolChart.png" by Cabot Health, Bristol Stool Chart is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institute of Health. (2018). Treatment for constipation.https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/constipation/treatment. ↵

- Digesting Food by Stanford School of Medicine and Khan Academy is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0. ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

Cells found within the lining of the stomach that secrete mucus as a protective coating.

cells in the gastric glands that produce and secrete hydrochloric acid (HCl) and intrinsic factor

Necessary for the absorption of vitamin B12 in the small intestine.

A digestive enzyme.

The digestive process where undigested materials are removed from the body as feces.