Chapter 2. Confederation in Conflict

2.8 Making Sense of 1885

According to one view, there were fewer than 400 insurgents directly involved in the Rebellion.[1] By any account, that makes it a very small civil war indeed. The impact of the events of 1885, however, was widespread and long lasting.

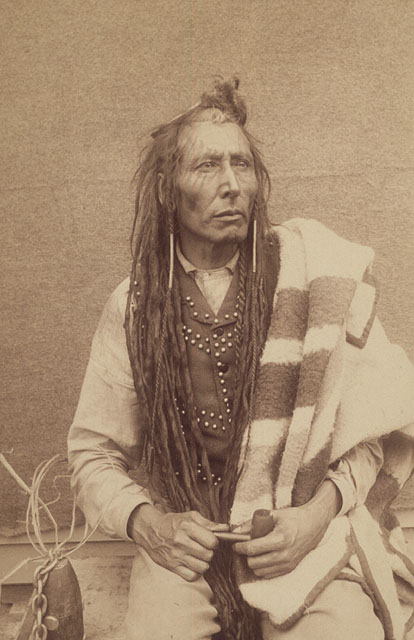

The rising gave Canada an excuse to imprison, punish, and more forcefully dominate members of the Aboriginal community on the Plains. Mistahimaskwa, who had lost credibility as a Cree leader, repeatedly attempted during the protest to rein in the frustrated and angry members of his community (including his own son), counselling peace and negotiation with the Canadians. He mostly failed in those efforts, although at Fort Pitt he was responsible for the safe passage of the Canadian population and the NWMP detachment. What’s more, as a leader, he stepped forward at the end of the unrest and surrendered himself to the Canadian authorities. He was charged with treason and felony, found guilty, but spared the noose. He received a three-year jail sentence which, for a 60 year old, was severe in its own right. Broken by the whole experience, he died shortly after his release two and a half years later.[2] A similar fate befell Pitikwahanapiwiyin (aka: Poundmaker), who served one of three years at Manitoba’s Stony Mountain Penitentiary before being released due to failing health. He died four months later. These events effectively decapitated Aboriginal leadership and resistance for a generation.

Assessing Riel

Notwithstanding his tactical and political errors in 1885, Riel served as a lightning rod for the Métis and their settler neighbours as well. As was the case at Red River, he proved effective at building collaborative and respectful partnerships among the aggrieved. At his trial, however, much hinged on the issue of Riel’s sanity.

Two experts (such as they were) declared that Riel was suffering from a personality disorder that took at least two different forms. The court was not convinced. For the Orange Lodge, still baying for blood after the execution of Thomas Scott in 1870, a successful insanity plea would cheat them of their revenge. For the Métis, it would look as though they had allowed themselves to be misdirected by a lunatic. As far as the government was concerned, a successful insanity plea would spare them the inevitable schism between Ontario and Quebec. Riel’s lawyers, too, had only one endgame in mind: keep their client off the gallows. It was to this end that Riel responded when he said, “while the Crown, with the great talents they have at its service, are trying to show that I am guilty — of course it is their duty — my counselors are trying — my good friends and lawyers who have been sent here by friends I respect, are trying to show that I am insane.”[3] Riel would have none of it. If he was declared insane, Riel argued, the reasonable demands of the Métis would be dismissed as well. The insanity plea collapsed.

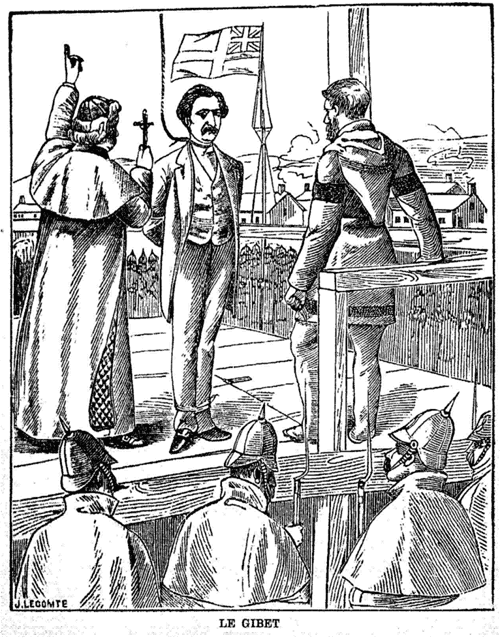

The court found Riel guilty of treason (though many believed he was being tried for the murder of Scott) and, despite a recommendation of mercy from the all Anglo-Protestant jury, the judge assigned the death penalty. Protest in Quebec rose up immediately after sentencing, putting Macdonald in the position of having to consider a second amnesty. In what soon became a famous affront to French Canadians, Macdonald declared himself resigned to the court’s decision and to Riel’s doom, “though every dog in Quebec bark in his favor.”[4] Riel was hanged in Regina on 16 November 1885.

It is safe to say that no figure in Canadian history has so divided Canadians and Canadian historians as Louis Riel. The Métis leader has been portrayed variously as a martyr, a murderer, a madman, and a messiah. The circumstances of his trial and execution divided French from English Canada, as the former embraced him as a representative of francophone and Catholic traditions. Insofar as the hardline Protestants of English Canada were concerned, yes, Riel’s Catholicism was a significant issue. Those Ontarians leading the charge into the West certainly had no appetite for a dualist society collaboratively built by French and English hands together. The Anglo-Protestants were inclined to unravel agreements that promised to respect cultural diversity. One result of the inhospitable climate created by Anglo-Manitobans and by the execution of Riel was a lack of migration from Quebec into the West.

Catholic Quebec’s relationship with Riel was not, however, nearly as straightforward. The Riel who re-emerged from exile in Montana was a changed man. He has been described by one of his many biographers as part of a larger global trend of nativist millenarians who represented Indigenous peoples under imperialism. The 1885 rising coincides, roughly, with the Ghost Dance movement in the the West and the Mahdi of the Sudan, both of which envisioned a world swept clean of the outsiders and newcomers.[5] In the case of Riel, his vision of cultural resurrection and a promised land for the Métis combined ultramontanist Catholicism with elements of numerology, as well as Mormon-style polygamy and a Saturday Sabbath. Some of these features of Riel’s belief system raised eyebrows among the Catholic clergy, and the most critical of them were prepared to have Riel excommunicated. For this constituency, he was not a hero — although his eleventh-hour reconciliation with the Church helped matters significantly.

For the Métis, of course, Riel’s failure of leadership and his apparent retreat into spiritualism raised mixed feelings. His record stands in sharp contrast with representations of Gabriel Dumont as a more hard-nosed and effective general. Riel was meant to be a galvanizing figure but, even among the Métis, he was frequently polarizing. Nevertheless, his execution brought home to the Métis their relative powerlessness in the face of Canadian imperialism in the West.

Anglo-Celtic Protestant Westerners celebrated the failure of the uprising and Riel’s execution for a generation or two. There was, however, a persistent undercurrent of concern that conditions that led to the rising were caused or manipulated by Ottawa. By the mid-20th century, anti-Ottawa feeling in Western Canada resulted in an ideological and symbolic resurrection of Riel. He was increasingly celebrated as a kind of founding father of Manitoba, among other things. Monuments appeared across the three Prairie provinces beginning in the late 1960s, and provincial premiers (even Conservatives) invoked the memory of Riel as a powerful symbol for Western alienation as when they engaged Ottawa in debates over resource revenues and constitutional issues. The radical left also embraced Riel in the 1960s and 1970s. His criticisms of Canadian capitalists and his resistance against the armed might of the state resonated in an era of anti-Vietnam War protests. Among the many streets and centres named for Riel in these years was a dormitory at politically stormy Simon Fraser University: Louis Riel House. Decoding the meaning of Riel requires that we engage with intent and see beyond the outcome. Perhaps the last word on this subject belongs to J.R. Miller, a distinguished historian at the University of Saskatchewan. He observed “It is a painful but real fact of life that the only thing that justifies rebellion is success. The successful revolutionary is a statesman, the unsuccessful a criminal.”[6]

Aboriginal people, for their part, have spent more than a century distancing themselves from Riel, claiming that they had their own very specific agendas (which they did), that they were not followers caught in the slipstream of the Métis nor of their charismatic leader (which they were not), and that no one else paid more dearly for the consequences of Riel’s “guilt.”

Key Points

- Riel’s trial and execution divided opinion in Canada and acted as a wedge between English and French in Ontario and Quebec.

- Riel’s legacy is a complex one in that he was vilified in the English-speaking provinces, lionized in French-Catholic Quebec, regarded with some suspicion by the Catholic establishment, treated with ambivalence by the Métis and First Nations, and subsequently held out as a symbol of Western and popular resistance in the late 20th century.

Media Attributions

- Poundmaker (Pitikwahanapiwiyin) © Oliver Buell, 1844–1910, Library and Archives Canada (C-001875) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Le Gibet © J. Lecomte is licensed under a Public Domain license

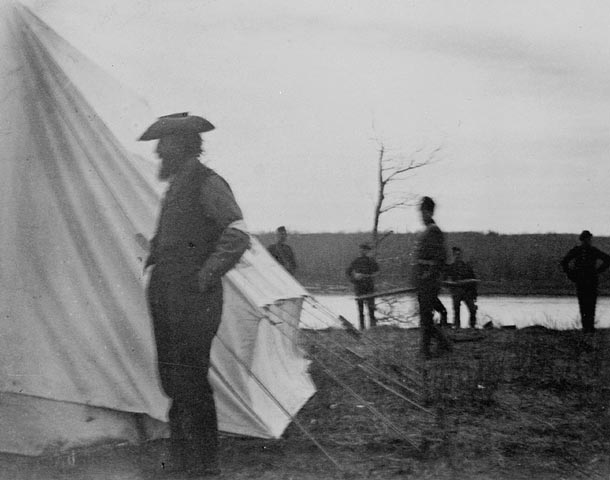

- Riel, a Prisoner © James Peters, 1853–1927, Library and Archives Canada (C-003450) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Jennifer Reid, Louis Riel and the Creation of Modern Canada: Mythic Discourse and the Postcolonial State (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2008), 1. ↵

- Rudy Wiebe, “Mistahimaskwa”, in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11 (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003), accessed 19 May 2015, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mistahimaskwa_11E.html. ↵

- Quoted in Douglas Linder, "The Trial of Louis Riel", (University of Missouri-Kansas City (UMKC), School of Law, 2004), accessed 15 May 2015, https://www.famous-trials.com/louisriel/855-home ↵

- Alan D. McMillan, Native Peoples and Cultures of Canada (Vancouver and Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre, 1988), 285. ↵

- Thomas Flanagan, Louis ‘David’ Riel: ‘Prophet of the New World’, revised edition (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996), 197-8. ↵

- J.R. Miller, Skyscrapers Hide the Heaven: A History of Indian-White Relations in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, rev. ed. 1991), 186. ↵

Movements among mostly Indigenous peoples under imperialism that attempt to throw off their occupiers and return to an idealized past way of living; sometimes imbued with a mystical element that could involve divine intervention.

Elements in Catholicism that emphasize papal authority over secular authority and, after 1870, papal infallibility. Seeks a large, extensive role for the church in daily life and objects to the main features of modernity, especially the growth of the secular state. Although ultramontanism faded in Europe after 1870, it remained a powerful force in Canada to the 1960s.