Chapter 3. Urban, Industrial, and Divided: Socio-Economic Change, 1867-1920

3.9 The Great War and the General Strike

The history of labour is simultaneously the history of industry and capitalism. No event so announces the triumph of industrial capitalism as does the first industrialized war in 1914-1918. The Boer War of 1899-1902 was a testing ground for new technologies like the Maxim machine gun and some refinements in artillery. It was nevertheless, a conflict marked by an old-style dependency on horses for moving troops and cavalry charges. What erupted in 1914 was very different. The most industrialized nations in Europe were now capable of producing arms, motorized land and air vehicles, armed and mobile artillery (tanks), and chemical weapons, and putting them all into the field of battle. A century of Industrial Revolutions across the northern hemisphere brought the world to this: the possibility of killing human beings on an industrial scale. And it had also produced large numbers of humans to kill.

Earlier European conflicts faced limits based on potential army size. There was always a balance to be struck between professional or mercenary regiments and the national armies. The latter became more the norm in the 19th century as the nation-state emerged. Nowhere was this more obvious than during the American Civil War. The standing army was a development that coincided with the rise of the Dominion of Canada (and fear of the American standing army was a factor in Canada’s expansion). There was also a trade-off, even during the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), between recruiting an army and depopulating the countryside. An army, as the saying goes, marches on its stomach. Early industrial nations had no recourse but to recruit from the farming population, but there was always a tipping point where too many soldiers would mean too little food.

Industrialization didn’t resolve that conundrum but it certainly changed the shape of the problem. Between 1750-1900 the population of Europe and Russia grew from about 146 million to 422 million; the population of the United States in 1775 was 2.5 million and in 1914 was nearly 100 million.[1] Canada’s population growth was hardly less incredible: from 90,000 in 1775 it grew to nearly 8 million in 1914. Some of this growth — particularly in North America and Russia — took place on agricultural frontiers, but everywhere across the combatant countries there were now millions upon millions of industrial workers who could be pressed into service without compromising food production. At the same time, essential industries required essential workers. Shipyards, coal mines, smelters, munitions factories, agricultural toolmakers, and the transport sector all had to be kept humming along. Still, strip away the so-called non-essential industries and there was a huge population of workers that might be transformed into soldiers. Canada alone would find 620,000 of them, only the slenderest fraction of whom were trained to be warriors before the war.

In 1914, no one knew with certainty how long the Great War would last (see Sections 6.2, 6.3, 6.4, and 6.5). It was meant to be “Great” in its importance, not its length or body count. It would prove to be transformative in many ways — globally and in Canada — and this is evident in the history of Canadian working people.

Labour at War

The military and political response of working Canadians — and Canadians in general — to the outbreak of hostilities in 1914, is considered elsewhere in this text. How labour (meaning working people and organized labour) met the experience of living in a country engaged for the first time in total war is what matters here. The foremost measure of working Canadians’ encounters with these new conditions is strike action.

The war began two years after a high-water mark in labour unrest. The year 1912 saw a spike in the number of disputes and, although this barely changed in the following year, the number of workers involved plummeted from 43,104 to 4,004. In 1914, there were half as many strikes and half as many days lost. The incidence and length of strikes would continue to fall in 1915 although the number of workers involved now began to rise and would continue to do so, doubling annually from 1914-1917. In 1917 — the year of Vimy Ridge and Ypres — there were 222 strikes with 50,327 strikers involved and over a million workdays lost. This marked a return to the levels of 1912.[2]

What lay behind the plunge in labour disputes and then the meteoric rise in job actions as the war progressed? Canada contributed more than half a million soldiers, sailors, and other participants to the cauldron of war, and most of those individuals came out of industry. This created job shortages and, as a consequence, unemployment levels fell sharply. As the war progressed, there were gaps on the shop floors in critical industries like armaments. These gaps were filled by recruiting women into the workforce. As a result of these developments, working class families experienced a rise in wages and living standards. Less than a year into the war and these changes were being observed (unevenly) across the country. Very soon, labour shortages gave unions an opportunity to negotiate better conditions and wages.

Working people faced several issues at once. While improvements were being noted in wages, prices were also rising. Income gains were quickly being eroded. New industries like munitions were being heavily supervised and routinized. Machinists, in particular, found their work more structured and managed — something to which they objected. Skilled workmen also bridled at the idea of women taking on factory positions that had previously been the preserve of craft union members. Women were, to be sure, a highly visible sign of deskilling and, thus, a lightning rod attracting the criticism of organized labour. Untrained men were also contributing to the deskilling process and were no less a source of unease for the trade unions.

Popular perceptions of the war also changed. Within two years of the declaration of war in August 1914, it was no longer a brief and glorious confrontation between the British Empire and its rivals; the Great War had descended into a relentless and inglorious meat grinder of a conflict. Aggressive army and navy recruitment drives and talk of compulsory service were met with calls for the conscription of capital and not just soldiers. It was becoming clear that throwing more men into the trenches was not a winning strategy, and working class critics began pointing to industrialists — profiteers — who were growing fat off government wartime contracts.

Finally, the role of the state was changing. The War Measures Act, 1914 gave the federal government extensive powers of censorship, arrest, and deportation, and control over the transportation sector (on land and in the harbours). It also allowed Ottawa to engage more directly in the manufacturing sector as a participant with a vested interest. As labour historian Craig Heron points out, the censoring of newspaper accounts of industrial disputes was viewed by socialists and labour leaders as an abuse of the Act; what’s more, the introduction of prohibition in 1917 was deeply resented.[3] As working-class unrest simultaneously spread across Europe and manifested itself in revolutionary socialist movements, the left wing in Canada came under surveillance by the RCMP and under fire from the Dominion government. Radical political organizations were infiltrated by police spies and suppressed; arrests and deportations of socialist leaders followed, which only aggravated labour’s unease. Labour organizations and left-wing political movements began to turn the official wartime propaganda line back on the government: these attacks on rights were, they said, nothing less than Prussianism or Kaiserism at home.[4]

The labour movement rebounded and union membership shot up. By the end of the War, there were no fewer than 378,000 members in craft and industrial unions, as well as in the emerging civic unions that now included police, civil servants, and white-collar workers. Craig Heron points to the exceptional levels of collaboration and cooperation between craft unions and even between craft and industrial unions; these alliances facilitated community-wide bargaining in smaller industrial towns and sectoral bargaining in larger cities. He also notes a greater spirit of inclusivity that extended to women and ethnic minorities in unions.[5]

Two factors contributing to labour’s growth remain to be mentioned. The first is success at the bargaining table. Wartime conditions, labour shortages, and a more muscular movement won concessions during strikes, and nothing succeeds like success when it comes to organizing labour movements. The second echoes the first: the success of revolutionaries in Russia inspired workers’ movements around the world. The possibility of wringing significant systemic reforms from the state and employers was in sight; the prospect of overturning capitalism entirely and establishing a socialist political, economic, and social order was also closer than ever before. These developments provide the material and intellectual context of events in 1919.

The General Strike

No single labour dispute in Canadian history is as well known and as regularly invoked as the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919. Lasting six weeks, from May through June, it constituted an important moment in the workers’ revolt of the period that began in the 1890s and concludes (or at least takes a break) in the mid-1920s. The events in Winnipeg are important in many respects, but it is important to note as well that general strikes sprang up elsewhere: in Amherst, Nova Scotia, Calgary, Vancouver, Victoria, and in many other centres from one end of the country to the other. Some of these strikes were motivated by local conditions and others in sympathy with Winnipeg.[6] Indeed, the rolling tide of disputes related to the Winnipeg General Strike would continue to 1925.

The idea of a work stoppage across industries had been touted for decades by the IWW and others on the more radical and industrial side of the labour movement. In the aftermath of the Great War, there were enough common issues and irritations to arouse the Canadian working class. As historian of labour, Greg Kealey, points out, “World War I, while providing specific sparks to light the flame of working-class struggle in 1919, should not be viewed as its cause.” [7] If not, then what causes lay behind a wave of unrest that brought out more than 149,000 workers in more than 400 strikes and claimed more than 3.4 million workdays lost in 1919?

Rising unemployment was a factor. The end of war meant the closing of munitions plants. Now, too, there were hundreds of thousands of returning soldiers to inflate demand for work. In addition, ex-servicemen expected to return to their old jobs, which meant displacing women and men who had been brought into those positions during the war. All of this created an atmosphere of uncertainty in the workforce while mobilizing, at least part of, a large female workforce in protest. Politically, too, the returned troops were something of a wildcard. Some were outraged at the anti-war and anti-conscription postures struck by many on the labour-left, to say nothing of their hostility toward the Russian Revolution and its supporters. There were also instances where returned British-Canadian soldiers turned their ire against Central and Eastern European, people they described as enemy aliens, who had taken their jobs. Other veterans felt that the radical critiques of profiteering, incompetent generalship in Europe, and international capitalism were entirely on the mark. Ottawa’s disinterest in the fate of returning soldiers pushed many veterans still closer to the labour-left camp.

Divisions between craft unions and industrial unions also played a role in the growing labour militance after the war. The old tensions resurfaced in 1918-1919, following an attack by the Trades and Labour Congress of Canada on radical (and mostly western) elements within the unions. Regional leadership subsequently met in Calgary in March 1919, to form a syndicalist organization with roots in the old IWW: the One Big Union (OBU). International locals in the west were quickly brought into the OBU fold. Workers who were impatient for a confrontation with employers responded favourably to the OBU’s radical language and rejected the AFL-TLC business union line. Precise numbers are impossible to obtain, but historians agree that anywhere from a quarter to a third of union membership in Western Canada — and specifically in Winnipeg — was in the OBU.

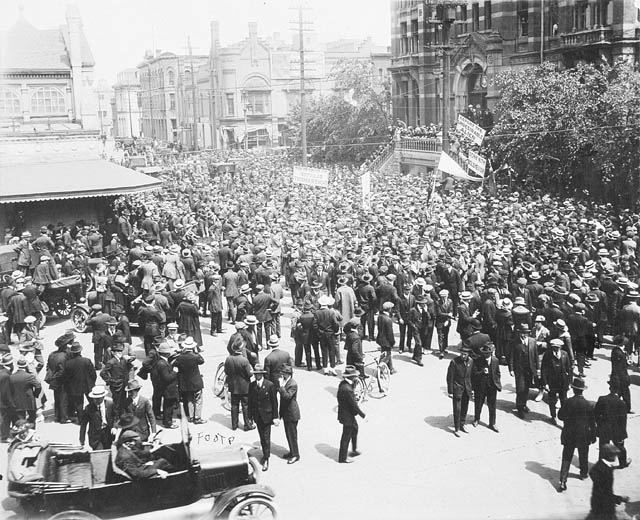

Of course, local conditions played a role. Events in Winnipeg arose initially from a bargaining dispute in the building and metal trades. The right to collectively bargain was one of the chips on the table and when employers would not budge, the Winnipeg Trades and Labour Council (WTLC) called for a general strike. The response was unprecedented. A few days later, approximately 30,000 Winnipeggers were on strike. Public transit, the factories, the police department, fire stations, retail shops, post offices, and several utilities closed down. The Central Strike Committee — established by the WTLC — bargained with the city and employers while authorizing essential services like milk delivery.

The Winnipeg establishment came out united in its opposition to the strike. A Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand was their coordinating body and they had deep pockets, a tight network of connections to the Borden government in Ottawa, and the full support of local and national newspapers. Describing the strike as a Bolshevik uprising (echoing fears of a Russian-style revolution) led by foreigners and traitors, the Citizens’ Committee turned attention away from the issue of collective bargaining and raised the spectre of a revolutionary crisis.

Matters came to a head in mid-June 1919. On the 17th of June, ten OBU leaders were arrested, among them the leading Social Gospel Methodist minister in Winnipeg, James S. Woodsworth (see Chapter 7). The mass arrest launched a demonstration of solidarity and a final buildup of state resources that collided on Bloody Saturday, the 21st of June 1919. The deployment of troops, Mounties, and Specials — volunteer police drawn from the Citizens’ Committee — in the words of one historian, turned Winnipeg into “virtually an occupied city.”[8] The Royal North-West Mounted Police (as the RCMP were called at the time) appeared and charged on horseback into the crowd three times before opening fire: 30 were injured and two killed. The federal government’s clear commitment to defeating the strike was manifest in cavalry charges against protesters, whose numbers included large numbers of Great War veterans. It was also evident in amendments to the Immigration Act and the Criminal Code that allowed Ottawa to deport British citizens and to charge strikers with sedition.

The Legacy of Winnipeg

The Panama Canal was an invisible participant in the General Strike. Opened in 1914, it cut deeply into the cost of shipping grain and lumber from Vancouver to the east coast of North America. The movement of Western products along the CPR through Winnipeg suffered badly. The effect was delayed by the War, but by 1919, it was being felt in falling wage rates and a rising cost of living in Manitoba. Winnipeg’s economy never fully recovered. A decade after the strike, the city slipped out of 3rd place among Canada’s largest centres and continued to become less and less consequential in the 20th century. One study has argued that the local labour unions were so demoralized by the events of 1919 and under such heavy state scrutiny, that they were thereafter incapable of fighting for competitive wages and working conditions.[9]

The strike produced other consequences, at least one of them very long-term. Six of the strike leaders were sentenced to a spell behind bars, some getting terms of two years. Woodsworth was released and almost immediately elected as an MP from the Independent Labour Party (ILP). He would go on to found the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), the precursor of the New Democratic Party (see Section 7.9). Other figures, drawn from the leadership ranks of the strikers, picked up the thread of revolutionism and established a communist political party.

Among historians, Winnipeg occupies a place of contention. Was it an expression of a peculiar kind of Western radicalism or part of a larger Canadian workers’ revolt? Does it constitute — as the Citizens Committee of One Thousand feared — a nascent Bolshevik revolution, or was it a local labour dispute with very limited goals: better wages and collective bargaining rights? These issues have divided labour historians for more than a generation. Recently it has been argued, perhaps unsurprisingly, that it was both a matter of local bargaining and a combination of radical rhetoric coupled to a comprehensive reaction by the authorities and the establishment.[10]

It has also been argued that the chief beneficiary of the Winnipeg Strike was the RNWMP. On the brink of being disbanded because its frontier mandate was no longer relevant, the Mounties found renewed purpose as an agency of state surveillance and subversion of leftist organizations.[11] What can be said with some certainty is that the events of 1919 hardened the federal and provincial state’s attitudes toward labour; collective bargaining rights, welfare, veterans’ support, and many other labour and social initiatives may have been postponed as a reaction to 1919. More pointedly, as one study reveals:

After crushing the Winnipeg strike, the federal government collaborated in the anti-radical Red Scare that businessmen and conservative journalists were promoting across the country. The workers’ revolt had thus pushed the state to create more powerful, centralized mechanisms for combating radicalism than had existed in pre-war Canada.[12]

At the very least, the events of 1919 determined the size of a labour union. The state was to restrict them in such a way that one big union would become an impossibility in the future.

Key Points

- The Great War created conditions that facilitated the growth of militant labour.

- The end of the war saw a sudden reversal for working people, the emergence of divisions between returned soldiers and workers, and a state crackdown on leftist labour organizations.

- The Winnipeg General Strike was the foremost of several similar disputes across Canada that pitted a broad-based alliance of working people against an economic elite combined with imperialist factions and the armed representatives of the government.

Media Attributions

- Street scene during the Winnipeg Strike of 1919 © Library and Archives Canada (PA-202201) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- War production, Canadian Linderman Co. Ltd. © Canada Dept. of National Defence, Library and Archives Canada (MIKAN no. 3371011) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Personnel of the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force with truck © Raymond Gibson, Library and Archives Canada (C-091749) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Street scene during the Winnipeg strike of 1919 © Library and Archives Canada (PA-202200) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Winnipeg General Strike © Library and Archives Canada (PA-163001) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Winnipeg riot © Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Library and Archives Canada (MIKAN no. 3615116) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Royal Northwest Mounted Police on Bloody Saturday © Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Library and Archives Canada (MIKAN no. 3615118) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Massimo Livi-Bacci, A Concise History of World Population, 2nd ed., trans. Carl Ipsen (Oxford: Blackwell, 1997), 31. ↵

- Gregory S. Kealey, Workers and Canadian History (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1995), 295. ↵

- Craig Heron, The Canadian Labour Movement: A Short History, 2nd ed. (Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, 1996), 47. ↵

- Craig Heron and Myer Siemiatycki, “The Great War, the State, and Working-Class Canada,” in The Workers’ Revolt in Canada, 1917-1925, ed. Craig Heron (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998), reprinted in Readings in Canadian History: Post Confederation, 7th ed., eds. R. Douglas Francis and Donald B. Smith (Toronto: Thomson Nelson, 2006): 372. ↵

- Heron, The Canadian Labour Movement, 48-9. ↵

- See, for example, David Bright, The Limits of Labour: Class Formation and the Labour Movement in Calgary, 1883-1929 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1998), 145-61, and Benjamin Isitt, “Searching for Workers’ Solidarity: The One Big Union and the Victoria General Strike of 1919,” Labour/Le Travail, 60 (Fall 2007): 9-42. ↵

- Gregory S. Kealey, Workers and Canadian History, (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1995), 294. ↵

- David Jay Bercuson, Confrontation at Winnipeg: Labour, Industrial Relations, and the General Strike, revised ed. (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1990), 187. ↵

- Kenneth McNaught and David J. Bercuson, The Winnipeg Strike: 1919 (Don Mills: Longman Canada, 1974), 118-20. ↵

- See Reinhold Kramer and Tom Mitchell, When the State Trembled: How A. J. Andrews and the Citizens’ Committee Broke the Winnipeg General Strike (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010). ↵

- See Lorne Browne, “Depression and Repression: Canada Between the Wars,” Canadian Dimension, vol. 49, issue 2 (March/April 2015): 27-37. ↵

- Heron and Siemiatycki, “The Great War”: 386. ↵

A full-time, permanent, usually salaried army, as opposed to a volunteer militia.

Sectors identified in a crisis (such as wartime) as fundamental to the survival of the economy or society or war effort. Workers in those sectors are typically protected against conscription and may also be restricted in their ability to move to other jobs. In some instances, the state takes direct control of the industries for the duration of the crisis or longer.

Describes the engagement of the whole nation in conflict, and not just the military. In the 20th century, applies only to the two World Wars.

Industrialists and others who were able to profit from government contracts in wartime.

Advocate of syndicalism, the belief that industry would be best run by syndicates made up of industrial workers who would own and operate the factories themselves.

During the Winnipeg General Strike, 1919, an organization established by the city’s business and political elites to break the strike and challenge the authority of the Strike Committee.

A workers’ party that led the Russian Revolution in October 1917 under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin.

A social reform movement stimulated by Christian beliefs that linked personal engagement with social salvation.

21 June 1919; during a mass demonstration of solidarity (after ten OBU leaders were arrested, including J. S. Woodsworth) in which a buildup of state resources (troops, Mounties and Specials) were brought in. 30 protesters were injured and two killed.

Volunteer police drawn from a local population; in the case of the Winnipeg General Strike, the Specials were recruited from the Citizen’s Committee.

A complex of political, social, economic, and cultural responses to the rise of pro-communist feeling in Canada and internationally; fear of communist revolution at home or abroad and particularly of pro-communist spies and supporters working clandestinely to advance a communist agenda; manifest in security campaigns against perceived enemies of the state, the creation of blacklists, and other acts of intimidation.