Chapter 3. Urban, Industrial, and Divided: Socio-Economic Change, 1867-1920

3.7 Limits of Democracy

The 1850s and 1860s witnessed the rise of a new class of political leaders and a new style of politics in British North America. The aristocratic airs of the Family Compact in Upper Canada and the HBC squirearchy on Vancouver Island were trademarks of a leadership caste on whom the sun was setting. In their place were men — and they were all men — of business, the law, and journalism. They were very much unlike their predecessors: wheelers, dealers, and professionals practiced at speaking and arguing a point. They weren’t without airs but they were willing to wade into a crowd and take on the mantle of populism. They were also men on the make; corruption, graft, and bribery were mainstays of Canadian politics. The Pacific Scandal was only the most consequential of what would be generations of pay-offs associated with the “railway hucksters” whose avarice and ambition, according to one historian, “plunged Canada into an orgy of railway overproduction.”[1] These conditions were not exclusive to Ottawa and federal politics: the railway binge in British Columbia that began in the 1890s and accelerated under Premier Richard McBride’s Conservatives was no less dubious in its ethics.

The culture of democracy in Victorian and Edwardian Canada was, effectively, an exclusive club. The federal government represented landowning farmers, merchants, and professionals — people who, by dint of their investment in the economy, were seen as stakeholders in the running of the country. And their qualifications were gilded, generally, by a better education. This is what privilege looked like in the late 19th century, and it helps to explain why the thought of overthrowing rather than voting out the government appealed to so many radicals in the labour movement and political activists on the left. It simply wasn’t their government.

The Franchise

The ballot box and Canadian-style parliamentary democracy held out the promise of an empowered public. The principle of responsible government was a premise of membership in the Dominion: it was seized upon by British Columbia when the colony became a province in 1871 and would be part of the package that created Alberta and Saskatchewan in 1905. What remained at issue was how to define that public. Who was the electorate and how (and when) should they be allowed to express their preferences and cast their votes?

For working people these questions were extremely important. An electorate made up of the wealthy would result in governments that were bound to be unsympathetic to workers’ concerns. As workers’ populations increased in urban areas, the disconnect between governments (civic, provincial, and federal) that represented economic elites rather than the majority of city-dwellers became more apparent. As well, urban working people sometimes found themselves at odds with rural Canadians.

In large measure these conditions arose because of property qualifications and other limits on the electorate. During the period from 1867-1920 the provinces decided their own electoral rules and, for many of these years, they determined the federal qualifications as well. These were based first and foremost on race and gender. With few exceptions, Aboriginal people simply did not have the vote. Nor did Asians. Nor, until the Great War, did women of any ethnicity or social class. What most constrained the size of the (male) electorate, however, were qualifications based on property and income.

In 1885 the Macdonald government brought control of the federal franchise back to Ottawa. Adulthood was defined as 21 years and an income qualification was added at this time: $150 annually for rural Canadians; $300 for urban Canadians. At this time $2 a day in factory wages was fairly good for men working a six-day week.[2] Keep in mind that stoppages occurred for many reasons, including weather conditions. To take one example, the relatively well-paid coal miners of Vancouver Island appear to have only worked a 222-day work-year on average, which severely cut into their apparent high wages of $3 a day. In short, while some working men might have made the income target, many others did not. Property-ownership requirements were a further, and longer-standing restriction on working people, the majority of whom rented their homes. Technically the 1885 Electoral Franchise Act made allowances for tenants but this, too, was deceptive. Federally and provincially, what appears to be universal male suffrage was in fact only extended to males who satisfied residence requirements. While this might be an easy bar to reach in rural areas and small towns, it was much more elusive in areas of high labour mobility. Where seasonal labour prevailed, conditions might be worse still. In an environment where winter conditions prohibited work year-round in the forests, on the seas, along canals, and in the fields, the requirement of 12 months residence in the constituency was for many working people the last and highest hurdle.

Whole classes of men were excluded from the franchise for reasons beyond their control. Legal barriers were erected to prevent Aboriginal men from voting in several provinces, and in British Columbia it was illegal for Chinese men to vote, regardless of their wealth. Macdonald’s Electoral Franchise Act, 1885 took on these limitations and extended them to Aboriginal peoples who had earlier been able to vote. What’s more, Macdonald exploited provisions for a federally-managed voters’ list that would be assembled by party loyalists. This had predictable results. Voter fraud and impersonation, arbitrary and purposeful sabotage of voters’ names on the electoral rolls (which could leave them unqualified to vote), and the buying and selling of votes continued to be part and parcel of Canadian elections well into the 1890s.

The Liberal government under Wilfrid Laurier was more favourably disposed to decentralized management of elections and passed the voters’ rolls back to the provinces. This time, however, the ability to discriminate on the basis of local biases was curtailed. Aboriginal voting rights remained entangled in a complex of rules but the direct obstacles to Asians voting were lifted and then re-imposed via literacy requirements. Manitoba similarly restricted Slavic voters by requiring literacy in English, German, French, or a Scandinavian language. Putting the provinces in charge meant inevitable national disparities. Property qualifications remained in place in Quebec and the three Maritime provinces. The overall effect was to create and to entrench rules that ostensibly gave the vote to every male, aged 21 or more, who was a British subject (Canadian citizenship having not yet been invented), but to perpetuate local quirks that could strip a Canadian of his federal vote the moment he crossed a provincial boundary line.

Labour’s Parties

Internationalism was a tenet of the socialist movement in the 19th century. But forging connections with labour organizations in Britain, let alone France or Germany, was an improbable task for Canadian workers. By default international became continental, as Canadian associations partnered up with larger American organizations. As a threat to the Canadian political elite, this was a kind of double-jeopardy: not only did the unions pose an apparent threat to the profit margin of Canadian businesses, they were aligned with organizations based in what many Canadians regarded as a (commercially and politically) hostile neighbour.

Despite the impediments, popular interest in electoral politics grew and by the 1880s the working class was making forays into electoral politics. One way they did so was through an American organization: Knights of Labor candidates began to run in Canadian elections. At the same time, middle-class Liberal and Conservative candidates were cutting their own cloth so as to appeal to workers, adopting policies and taking positions that echoed working-class concerns. The Tories and the Grits even endorsed working men in single-industry towns to run for office under their respective banners. The mainstream parties certainly made efforts to attract worker votes, and they embraced a more inclusive political rhetoric to that end.

For a while something similar happened in Britain and the other White Dominions. The Liberal government of Prime Minister William Gladstone won the loyalty of more than a generation of working-class British voters by significantly broadening the franchise to working men. In response, in the 1880s, British trade unionists and social reform-oriented intellectuals made their way into Gladstone’s Liberal Party and ran for election (with some success) as Liberal-Labour (Lib-Lab) candidates. More definitively, working-class parties also emerged: the Scottish Labour Party was founded in 1888 and the Independent Labour Party in 1893. In 1900, the Trades Union Congress (the British equivalent of the TLC) established the foundation of what later became the Labour Party in 1906. Parallel events occurred in Australia (from 1891) and New Zealand (between 1901 and 1916) but not in Canada. Why did turn-of-the-century Canadian labour move in a different direction?

The TLC’s close ties with the AFL offers an explanation. In the United States, the AFL favoured a strategy of pitting the Democrats against the Republicans on workers’ issues. The AFL’s leader, Samuel Gompers, took the view that labour should “reward its friends and punish its enemies” at the ballot box, and did not offer up an independent partisan alternative. As the AFL’s influence over the TLC grew, the door closed on a labour-left political alliance in Canada. Gompers regarded the socialists with contempt, describing them as “political healers,” akin to faith healers and mystics whose commitment to workers’ conditions was secondary to winning power. He was in favour, instead, of getting trade unionists elected to office who would then change the attitudes of the major North American political parties from the inside. The TLC followed this course and in 1902 voted the Knights out of the Congress’ membership and kept the SPC at bay. Direct involvement in politics by the TLC would have to wait until the 1960s.

The TLC’s strategy in the early 1900s was to run sympathetic candidates in the Liberal Party (generally regarded as more favourably disposed toward unions, at least until about 1906) and this met with some success. Canadian Lib-Lab candidates promoted an agenda of labourism, which consisted mostly of democratic reforms, the eight-hour day, a minimum wage, and educational opportunities for all.[3] The TLC in 1906 considered establishing a Labour Party but the British Columbian delegates saw this as too moderate an approach and established the Socialist Party of BC (SPBC). Other provincial labour centres then began generating parties of their own. In Manitoba, Ontario, and Nova Scotia, Independent Labour Parties appeared. Credible candidates ran successfully in urban and mining districts. A Labour Party competed in elections in Quebec, principally in Montreal.

Ideological differences separated these various tactics and parties. As each organization grew stronger and as factionalism continued to grow, the opportunities for forging a national alliance receded. The first two decades of the 20th century would see the emergence of a distinct strain of revolutionary socialism on the West Coast that was profoundly out of sync with the rest of Canada’s labour movement, particularly those elements most influenced by what was going on in Britain.[4] This left wing of labour’s political arm rejected reformism and was stridently uncompromising when it came to capitalism and even more so when it came to labourist gradualism— and it was popular. Between 1907-1909 the SPBC’s support grew from 10% to 22% of the provincial vote and it elected two members of the legislative assembly. Its career thereafter is considered further in Chapter 8.

One Man, One Vote

If ever there was a golden age of Canadian democracy, it won’t be found in the years before the Great War. Middle-class arguments for inclusion in a democratic order revolved around the idea of being invested in a community: having a home, a residence, a business, and being part of that wealth-generating class that at first drove the market towns and was now building the industrial cities. Giving the vote to working men who lacked wealth, education, and property, not to mention a permanent residence in the community in which they proposed to vote, required a significant readjustment of principles. There were, too, those who expected working men to vote as their employer told them to. This was, in fact, how things worked in the days before the secret ballot, which only arrived in most parts of Canada in 1874.

In short, democratic avenues to social and political change were not especially welcoming to working people. Efforts were made to make it otherwise, but it would take the transformative power of a World War to effect real changes. Organizations like the Knights stand out as an early attempt to lay claim to the politics of identity: they articulated a kind of class consciousness — one based on the dignity of labour — but they were not socialists. Where the impact of the Knights was more lasting was in its role as a movement of reform. It offered a critique of the values of late Victorian capitalism that survived in various forms for generations.

Key Points

- Democracy in early post-Confederation Canada was limited by income, property, residence, race, and gender.

- Provincial restrictions on the franchise influenced federal rules as well.

- Political organizations representing labour and/or working people did not develop in Canada the same way they did in other parts of the British Empire.

- Labour’s political strategies often involved supporting the Liberal or Conservative parties, although the hard left ran socialist candidates.

Long Descriptions

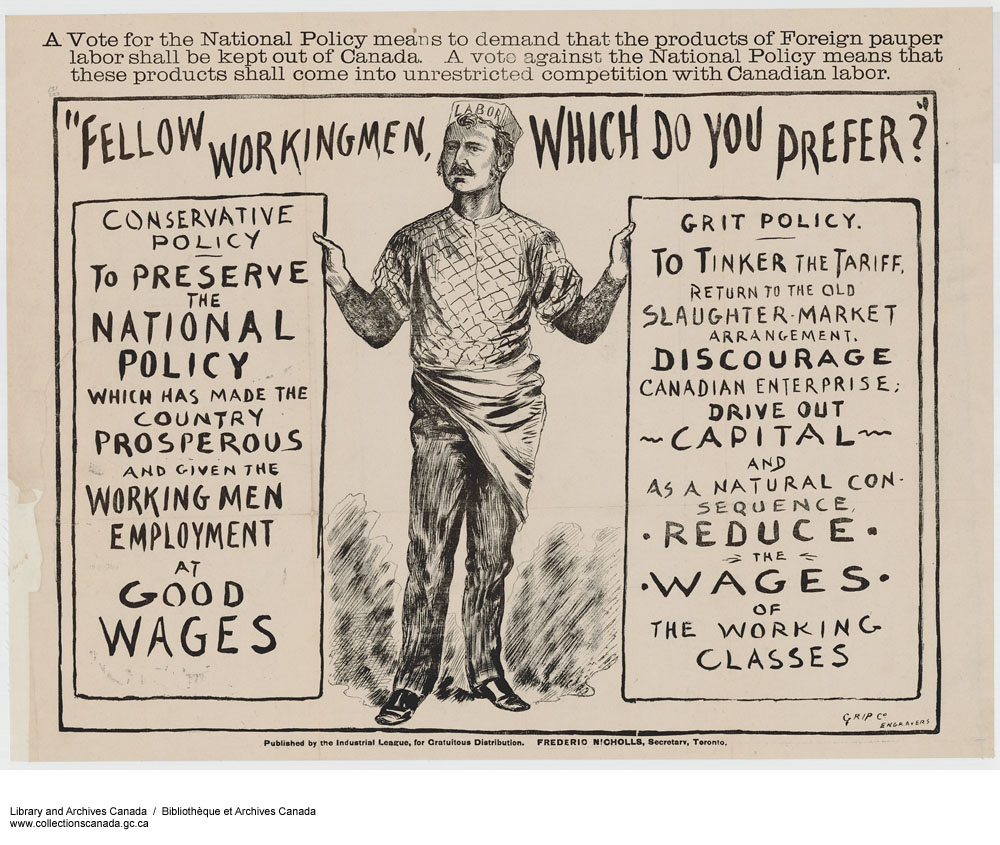

Figure 3.38 long description: Conservative Party advertisement in favour of the National Policy. The top of the notice reads “A Vote for the National Policy means to demand that the products of Foreign pauper labor shall be kept out of Canada. A vote against the National Policy means that these products shall come into unrestricted competition with Canadian labor.”

Below is a cartoon of a man wearing a hat labelled “Labor” holding two signs. He says, “Fellow workingmen, which do you prefer?” The sign on the left says “Conservative Policy: To preserve the National Policy which has made the country prosperous and given the working men employment at good wages.” The sign on the right says “Grit Policy. To tinker the tariff, return to the old slaughter market arrangement. Discourage Canadian enterprise; drive out capital and as a natural consequence, reduce the wages of the working classes.” The cartoon is signed by Grip Co. Engravers.

The notice is published by the Industrial League, “for Gratuitous Distribution,” and signed by Frederic Nicholls, Secretary, Toronto. [Return to Figure 3.38]

Media Attributions

- A Vote for the National Policy, 1891 © Library and Archives Canada (MIKAN no. 3939876) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Bryan D. Palmer, Working-Class Experience: Rethinking the History of Canadian Labour, 1800-1991, 2nd ed. (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1992), 82-3. ↵

- Information on wages in the 19th century is difficult to come by and few studies extant offer comprehensive data. The Royal Commission on the Relations of Labor and Capital of 1889 interviewed workers and supervisors who generally placed men’s wages between $7 and $15 per week. Women’s wages were typically half that of men, and children’s wages sometimes half again. ↵

- Palmer, Working-Class Experience, 177. ↵

- Donald Avery, Reluctant Host: Canada's Response to Immigrant Workers, 1896-1994 (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1995), 64-5. ↵

The elite network in pre-Confederation Canada that dominated colonial politics; in Quebec (aka: Canada East, Lower Canada) it was referred to as the Chateau Clique.

Colloquial term used to describe the elite in colonial British Columbia.

In politics, an appeal to the interests and concerns of the community by political leaders (populists) usually against established elites or minority — or scapegoat — groups. The rhetoric of populists is often characterized as vitriolic, bombastic, and fear-mongering.

Extension of the franchise — the right to vote — to all adult males. In practice in Canada, it excluded non-Euro-Canadians (i.e. Aboriginal and Asian) adult males until the mid-20th century. Also constrained by residency requirements until the mid-20th century.

Typically a pro-labour candidate, sometime running under a Labour or Independent Labour banner, who joined the Liberal caucus on being elected.

In Britain, the political face of the Trades Union Congress; established in 1906. While Labour Parties also appeared in Australia and New Zealand, one never fully materialized in Canada.

Canadian Liberal-Labour (Lib-Lab) candidates promoted an agenda that consisted mostly of democratic reforms, the 8-hour work day, a minimum wage, and educational opportunities for all.

The idea that great change can occur incrementally, in slow, small, and subtle steps, rather than by large uprisings or revolutions. Among left-wing activists, a belief that reforms to capitalism can produce a social and economic order of fairness for working people; sometimes called “Fabianism;” derided by revolutionaries as delusional. In the context of Quebec’s independence movements the equivalent term is étapisme. See also reformist and impossibilist.