Chapter 1. Confederation and the Peoples of Canada

1.4 Contributory Factors of Confederation

Confederation answered constitutional questions about Canada’s organization and governance, but it was also an economic strategy, and it had a military and diplomatic face as well. British North Americans bought into the new federal structure in part because it promised a more certain future. Its success, to some extent, has to be measured against these concerns.

Civil War America

The American Civil War in the 1860s, coming to a close in 1866, consumed the United States. It entailed carnage on a massive scale and national productive capacity was severely damaged. It did, however, leave the United States with the largest standing army on the planet, and it was a battle-hardened army at that. The Aboriginal peoples of the western half of North America would see this massive military machinery deployed in their territories. British North Americans had cause to be concerned that they would confront this military machinery as well.

British diplomatic missteps during the Civil War hardened American opinion against both Britain and British North America. The Reciprocity Treaty of 1854—which enabled freer trade between the colonies and the United States—was cancelled by the Americans at the end of the war. Fear grew of further retributive moves by the Americans. Indeed, a series of largely ineffectual invasions of British North America (BNA) by Irish-Americans, bound together as an anti-British Fenian Army, catalyzed colonial will to build a united regime that would offer greater mutual protection. Invasions took place across the borders of the three contiguous BNA colonies (Canada East, Canada West, and New Brunswick), and of those that were spared, Nova Scotia, PEI, and British Columbia shared in the sense of pending attacks. American acquisition of Alaska, in 1867, reminded British Columbians and other Westerners that the Americans held on to their belief in a manifest destiny to rule the whole of the continent.

Was a Canadian federation any more able to defend itself against an American invasion than the separate colonies? Probably not. The population discrepancy between BNA and the re-United States as well as the enormity of the experienced American forces, not to mention the superiority of American arms, makes the question absurd. Confederation reduced British military obligations and did little to increase the size and preparedness of Canadian militias. It did, however, create the impression of unity and an emergent nation state, rather than low-hanging colonial fruit that might be picked at the convenience of the United States. The emergence of a Canadian military culture after 1867 was slow in coming, and the almost calamitous performance of militia units in the North West Rebellion in 1885 only underlines the extent to which fear of America did not result in any palpable steps to improve Canadian defense.

A Post-Mercantilist World

In the mid-19th century Britain moved inexorably toward freer trade. Laissez-faire capitalism became the order of the day. For the BNA colonies, this meant an end to preferred access to markets in the British Isles. Reciprocity with the United States was a step designed to offset market losses across the Atlantic. The end of Reciprocity raised serious questions about whether the British North American economy could survive. Confederation, in this context, was represented as a commercial as well as a political union. Clearly, the colonies could have achieved commercial union without putting political union on the table as well; the former did not necessitate the latter. After all, the point of reciprocity with the United States was to prevent political annexation, not pave its way. Nevertheless, federal union held out the prospect of improved inter-colonial trade.

There are problems with the inter-colonial trade scenario, the foremost of which is the absence of complementary products. All of the BNA colonies from Canada West (Ontario) to the Atlantic Coast produced lumber, shipping, mostly the same cereal crops, and fish. What was left to trade? Increasingly coal and iron ore were considerations, but these would benefit few Canadians directly. For Canada East (Quebec) and Canada West (Ontario) in particular, the two Maritime provinces were hardly a substitute for the millions of customers south of the border. Nevertheless, the prospect of new infrastructure connecting the colonies, access to ice-free ports in Halifax and Saint John, and accelerated trade was yet another reason presented for pulling the colonies together into some kind of union.

The Railway

Commercial success was predicated on the idea of a railway. The Intercolonial Railway had been touted for years before Confederation, and it was so central to the whole project that it is enshrined in Section 145 of the BNA Act (1867). It took another decade to complete, and its round-about route far from the American border — via Chaleur Bay and the Miramichi Valley — reflected the contemporary fears of an attack from the United States, but this was meant nevertheless to be a key element in the economic union. Obviously the colonies might have built a railway regardless of Confederation. Less obviously, the railway itself was an engine for economic growth: Railways require miles of steel rails, thousands upon thousands of wooden ties, and significant rolling stock as well. The Intercolonial and the railways that followed its construction were thus meant to do more than connect economies: they were meant to generate industrial activity.

Key Points

- British North Americans saw in Confederation a solution to several pressing issues.

- The American Civil War and the Fenian Invasions compelled border colonies to consider unification as a step toward improved defence.

- The loss of Reciprocity and the introduction of Free Trade encouraged colonial elites to find ways to increase intercolonial commerce.

- Railway technology held out the promise of greater security, increased intercolonial trade, and an industrialized economy.

Media Attributions

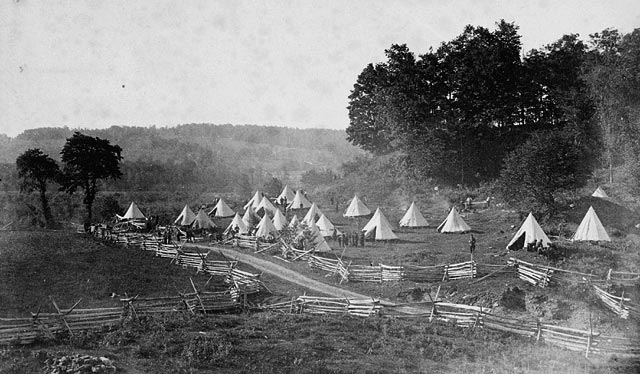

- Pigeon Hill Camp of the 60th Battalion © William Sawyer, 1820–1889, Library and Archives Canada (C-033036) is licensed under a Public Domain license

1854 agreement between the British North American colonies and the United States; enabled freer trade; was cancelled by the Americans at the end of the Civil War.

Irish-Americans, bound together as an anti-British army; mounted and/or threatened invasions of British North America in the 1860s and ’70s.

American notion that it could control, and was destined to control, the whole of North America; literally, it was the will of God (destined) and it was apparent (manifest) in the incremental territorial expansions of the United States.