Chapter 3. Urban, Industrial, and Divided: Socio-Economic Change, 1867-1920

3.5 Urbanization and Industry

Industrialization took place in existing cities and it called into existence new — industrial — cities. There was, therefore, a changing urban landscape in some cases, but also a kind of urban template was developed for emergent cities, onto which industrial relations were imposed. Cities were sites of class struggle and the negotiation of new social relations, regardless of whether they were Canadian metropolises or small mining towns like Greenwood, BC or Frank, AB. The common denominator was the role that capital played in creating landscapes and cityscapes that gave priority to productive processes, sometimes with a brief horizon in mind.

The Dominion of Cities

Between 1871-1911, the population of Canada nearly doubled, from 3,689,000 to 7,207,000.[1] Most of that growth was in urban areas as the share of the workforce engaged in non-agricultural pursuits rose from 51.9% to over 60% in the same period. [2] Even in Nova Scotia, where the benefits of industrialization were not long lasting nor very deep, the impact on the scale of urban settlements was very dramatic: in the decade after Confederation, Halifax grew by 22%, New Glasgow by 55%, Sydney Mines by 57%, and Truro by 64%. From 1891-1901, a decade of immigration strongly associated with the growth of population and farm settlement in the West, Sydney tripled in size, emerging as the second largest city in the province.[3]

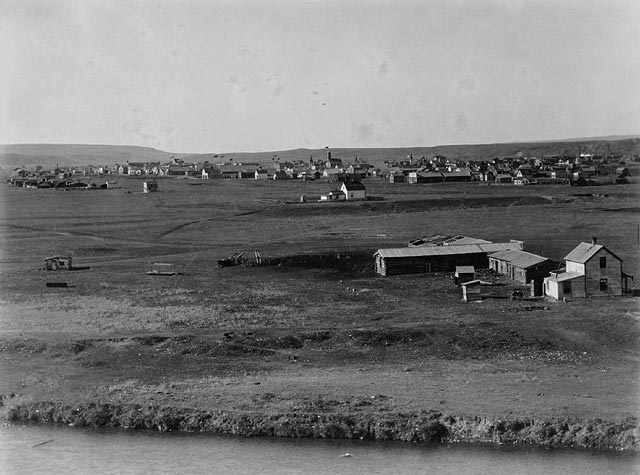

These figures, respectable though they were, are totally eclipsed by the growth of Western towns and cities. Calgary held fewer than 4,000 people in 1891, and added only 500 over the next 10 years. Then its population leapt to 43,704 in 1911 and 63,305 in 1921 with an economy built mainly around distribution, food processing (e.g., meat packing), and housing materials.[4] In 1891, Winnipeg became the first western city to join the ranks of the 10 largest centres in Canada, arriving in ninth spot with a population of 25,642. The very next census saw it pull ahead of all the Maritime cities (including Halifax), and in 1911, it was the third largest city in the country, with 136,035 people. Likewise, Vancouver joined the top-10 in 1901, with only 26,133 people, and moved into fourth place in 1911 with 120,847. By 1921, four of the 10 largest cities in Canada were in the West, but the older eastern members of this club of leading cities were not going to be easily overtaken. Ottawa, after all, doubled every 20 years from 21,545 in 1871 to 44,156 in 1891, and 87,082 in 1911; the Dominion capital passed the 100,000 mark by 1921, but by that time its population had dropped from its best ranking of fourth (in 1901) to sixth.

None of these cities was without an important industrial component. Vancouver, Calgary, Regina, and Winnipeg each had important rail yards and repair shops associated with the CPR (as did, to a lesser degree, Kamloops, Medicine Hat, and Brandon). Industrializing the production of food was another shared feature, whether in the form of canning salmon or packing meat or shipping enormous quantities of grain. Housing materials was also important to the regional booming population. Door and sash factories and lumber mills appeared in all of the biggest cities, in addition to other expressions of industrialism such as printers, cigar makers, and newspapers. Each of the western cities, too, had a role to play in goods distribution. This involved the handling of foodstuffs and construction materials needed by an increasing population, but also the manufactured goods produced in central Canada. An example of this is the distribution system developed in the 1890s by Toronto department store owner Timothy Eaton (1834-1907). Warehouses for Eaton’s goods were built in the major centres but actual stores only appeared in the West in 1905. In the meantime, one could order from catalogues and have delivered a huge variety of manufactured products — including houses as buildable kits.

What is conspicuous by its absence from the western cities at the turn of the century is heavy industry. Textiles did well for a while in Winnipeg, but steel manufacturing and the production of machinery both remained an effective monopoly of central Canada. When the automobile industry arrived in Canada, it was in Walkerville and Montreal, not Edmonton or New Westminster (let alone Halifax or Charlottetown). Processing primary products with very little value added was the norm in the West. It is partly for this reason that workers in the emergent service industries — streetcar drivers, milk deliverymen, fire fighters — were important players in the trade union landscape of the West.

While urbanism was spreading alongside industrialism and capitalism, the power of Montreal and Toronto was growing greater with each passing generation. In 1871, there were slightly more than 100,000 people in Montreal; Toronto — at 56,092 — was slightly smaller than Quebec City. By 1891, Montreal had a population of nearly 220,000 and Toronto was three-times the size of Quebec City at 181,000. These two economic and industrial centres were rapidly emerging as a first-rung category of cities, the country’s two metropolises. In 1911, the census found nearly half a million people in Montreal and 380,000 in Toronto. By the end of the Great War, both had passed the half million mark and the next nearest city, Winnipeg, was less than half as large with fewer than 200,000. Toronto’s rate of growth and transformation was more sudden and spectacular than Montreal’s but both were, even in 1900, nothing like what they had been in 1867. Both cities hosted large manufacturing operations, as did second- and third-tier cities in Ontario and in Quebec’s Eastern Townships. In the immediate catchment of each of the two major cities, a metropolitan influence was obvious as the local economies became more closely knit. The foremost example of this is the so-called “golden horseshoe” at the western end of Lake Ontario: Toronto was the unchallenged heart of this conurbation that grew (and became an almost continuous urban sprawl) through the 20th century.

The links between the second industrial revolution and urbanization are described by historian Craig Heron (York University).

Urban Conditions to 1920

City growth is a companion process of industrialization and, as we have seen, industrialization was enabled by Confederation. Maritime historian, Larry McCann, captured this when he wrote, “The transformation of Nova Scotia’s economic structure and the growth of its towns and cities in the post-Confederation period occurred simultaneously with the province’s integration into the continental economy.”[5] Larger factories replaced smaller shops and these factories, of course, were located in towns. Opportunities to earn cash wages attracted young people off the land, especially those who were unlikely to inherit the family farm. Newcomers from abroad, naturally, came ashore in large port cities and those port cities were the outlets for manufactured goods. The ability to consolidate dumps of fuel, whether wood or fossil fuels, was greater in cities that had port and rail, or even canal facilities. The cities, too, were centres of finance, and industrialism was nothing without capital.

Sean Kheraj (York University), a historian of environmental questions, considers the function and meaning of parks – specifically Vancouver’s Stanley Park – in the context of modern cities.

The effect was a self-reinforcing pattern. Factories moved to towns that had financial credibility (that is, either wealth or the ability to borrow wealth), infrastructure (docks, railyards, etc.) and an established workforce. This was the case in 1879 when Hart Massey closed the last of his agricultural implements business in Newcastle, ON (where it had moved in 1849 from the tiny inland village of Bond Head) and relocated everything to Toronto where it merged with its chief competitor. By 1891, Massey-Harris employed nearly 600 people.[6]

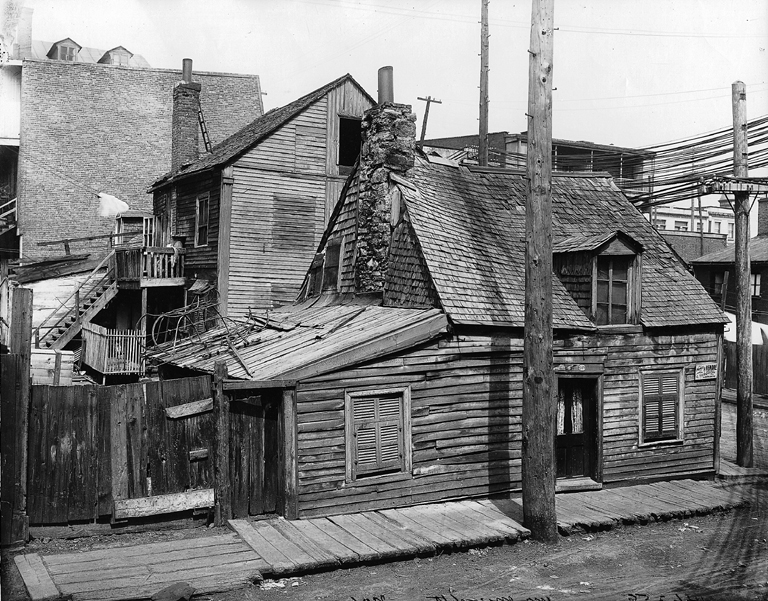

While the competition was visibly fierce for investment, giving rise to a generation of civic self-promoters called boosters, it was no less pitched when it came to attracting and retaining a population of wage-earners. It was the ability of Canadians and immigrants to move from town to town in search of work that made industrialization possible. Free labour (untied to the land or to a feudal relationship) was fundamental to the transition to industrialism. This worked well enough when the economy was surging and opportunities beckoned. But when the economy troughed, workers found themselves effectively trapped in the cities where they last hoped to find work. The 1870s, for example, were marked by dramatic protests and hardship in Ottawa, Montreal, and other centres as families complained that they were starving for want of work. In Toronto, the local House of Industry received 2,000 applications for refuge between 1879-1882.[7] Cities might create circumstances in which building rental housing for an emergent working class was both necessary and remunerative. In becoming a tenant, however, workers exposed themselves to impermanence and the possibility of eviction. If they lived in tied housing and carried debt at the truck shop or company store, their vulnerabilities could be greater still.

Overcrowding was widespread. Health conditions were often poor. Sewage systems were deplorable and only began to improve in the 1890s in most Canadian cities and towns. Water supplies were regularly tainted. Immigrant, Aboriginal, and African-Canadian neighbourhoods generally endured worse conditions than those occupied by Anglo- and Franco-Canadians. Housing in some industrial areas was more like dormitories than apartments because of the extensive occupancy of single men and single women. These conditions prevailed at the very time when wealthy and leafy suburbs were being created for the owners of industry. Generally located upwind from the smoke and noise of factories and mills, these wealthy “Nob Hills” paid obeisance to the capitalist hub of Canada — Montreal — and the power of the CPR’s elite in their names. A Mount Royal neighbourhood occurs in cities all along the main CPR line. Vancouver’s upper-class Shaughnessy neighbourhood was named in 1907 for the then-president of the CPR, and there are Van Horne streets in cities across the country. The hundreds who worked in the switching and freight yards thus lived downwind and often downhill from their economic superiors and employers. Cities had always had elements of spatial segregation based on class and role, but this was being imposed on Canadian cities in a very purposeful way. Awareness of these differences in quality of life and experiences was not unusual.

Single Industry Towns

Nanaimo, on Vancouver Island, and Sydney, NS are good examples of industrial-era towns with effectively no prior market-town existence.[8] Instant cities of this kind quickly boasted of having the urban amenities found in other 19th century cities: libraries, schools, concert halls, breweries, hotels, restaurants, and newspapers.

The small and new industrial towns generated urban problems as well. The shocking infant mortality rates of industrial Montreal in the last quarter of the 19th century — running to 285 deaths out of every 1,000 births — barely surpassed Nanaimo in 1881 with 250 per 1,000 births. Kamloops, a booming railway and lumber mill town built atop a cattle and fur trade settlement (not to mention ancient Aboriginal villages), had an infant mortality rate of 380 of 1,000 births in 1891.[9]

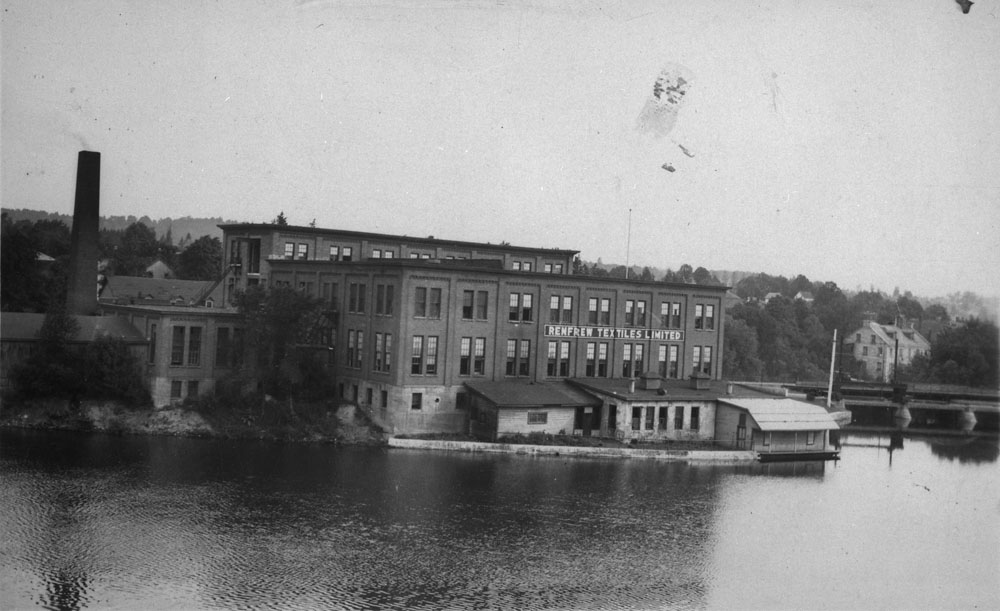

What Nanaimo and most the Cape Breton mining towns had in common was the fact that they were essentially single industry communities. The same was true of Drumheller (from 1911), the Crowsnest Pass colliery towns, the Kootenay hardrock mining towns, and a great number of lumber mill towns across the Maritimes and much of the rest of the country. In British Columbia, there was a cohort of 25 towns with population of between 500 to about 2,000 people that sprang into existence around 1891. These were primarily mining towns and the largest share of them were in the Kootenays. Only a handful existed a decade earlier and some would become ghost towns by 1911.

In some instances, these communities were not just limited by a lack of variety of employment opportunities: they were in essence (or formally) company towns in which the chief employer was also the landlord, and possibly responsible for civic authority as well. Communities like these were many and they proved to be highly vulnerable to changes in the economic weather. As one historian of a New Brunswick cotton textile town observes, “by 1890 there were over one hundred villages comparable to Milltown. These small towns contained over 4,500 industrial establishments representing over $2.5 million of invested capital and almost 25,000 jobs.”[10] The same historian adds that these small industrial nodes constituted “only one-fourteenth of the industrial capacity of the 46 major Canadian cities,” and yet the pattern was cast widely and echoed many of the developments witnessed in larger centres. There were representatives of this tier of industrial centres in every province and they were an important part of the Dominion’s web of industrial activity.

Exercise: History Around You

Street by Street

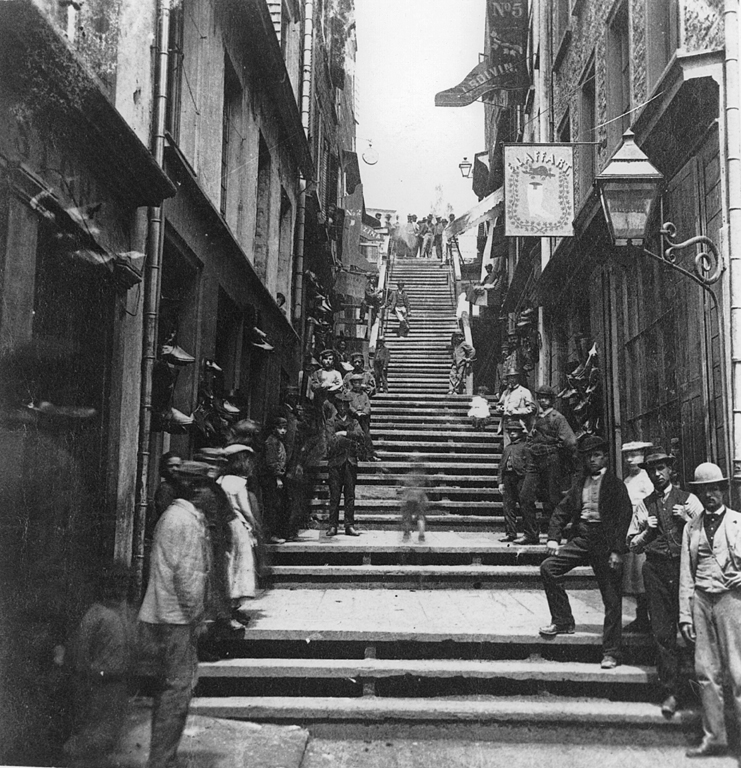

The transportation systems of the past leave indelible fingerprints on the dimensions of our cities. Take a look at the oldest part(s) of your city or town. How wide are the streets? If you live in Lillooet, BC, for example, they’re extremely wide. That’s also the case on the main streets of downtown Winnipeg. In Vancouver’s Gastown, Water Street is perhaps a quarter as wide. In the Old Town of Quebec or around Montreal’s Ville-Marie they are narrower still, as they are in the heart of St. John’s.

Can one conclude from this that people in the past were much thinner than they are now or that Winnipeggers need wider roads to negotiate a turn?

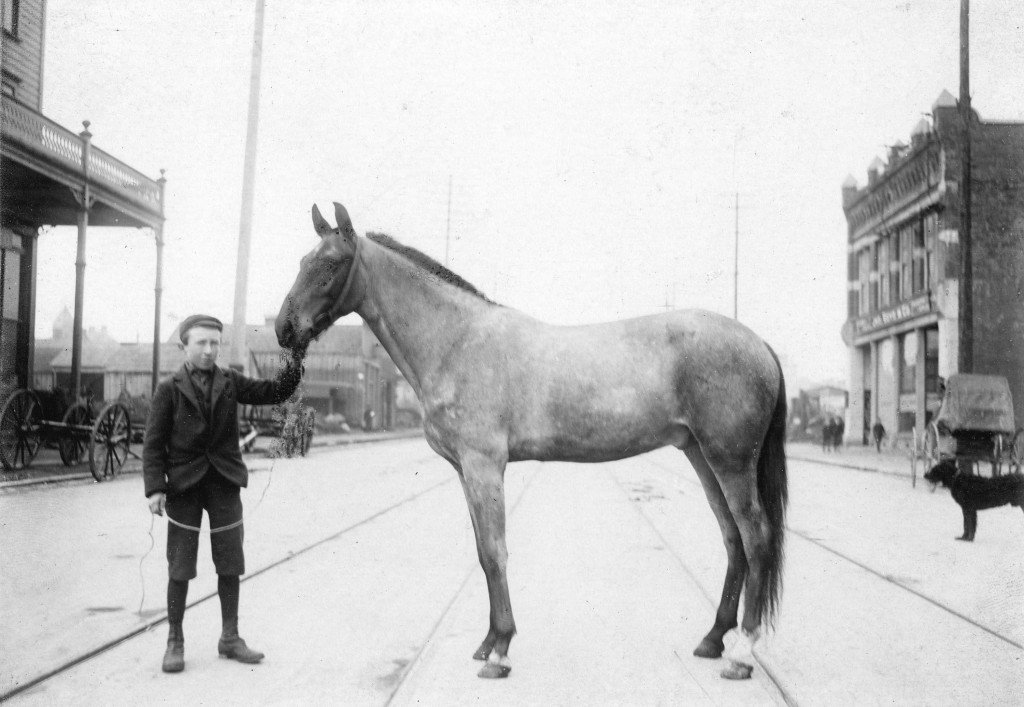

The answer can be found in the dominant transportation technology of the day. St. John’s, Montreal, and Quebec were built with military concerns in mind and some of the topography was (and is) challenging, but what distinguishes them most from later cities is that horses were rare. Most of the carting that was done was powered by human legs. And the turning radius of a handcart is very narrow. Merchants shipping goods into the Cariboo gold towns via Lillooet had something in common with Métis freighters in Winnipeg: they made use of ox teams. The turning radius of a team of oxen pulling a wagon is necessarily very large. In between are the cities where horse traffic dominated. The warehouses of Gastown, in Vancouver, depended on fleets of carters whose moderate-sized horses had to be able to make a U-turn with a small wagon in tow. Multiple horse teams pulling larger wagons required more space — though not as much as a team of oxen — and that transition can be seen in slightly later street layouts.

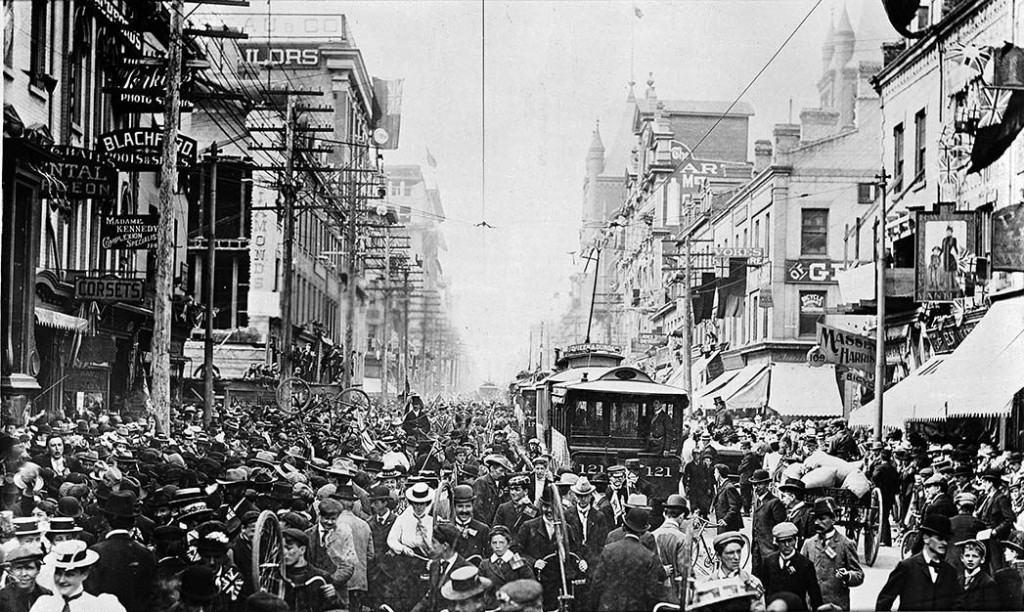

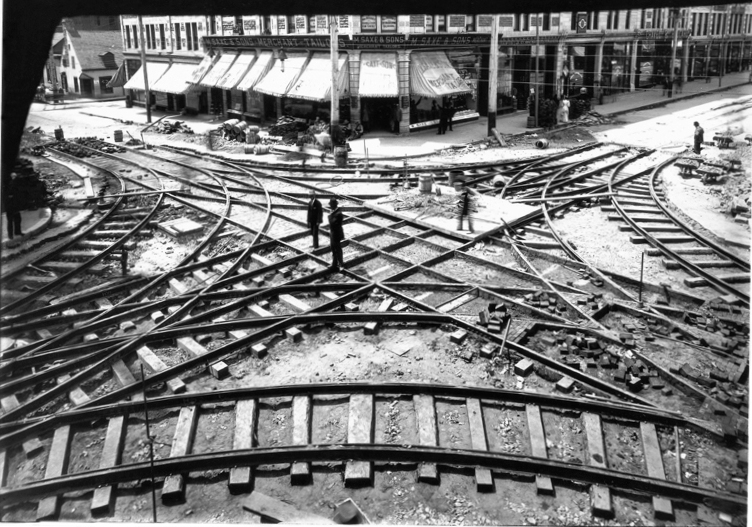

Late 19th and early 20th century cities were typically horse towns. The introduction of streetcars added a new wrinkle, as can be seen across Vancouver where the streetcar system rapidly outstripped the building of neighbourhoods. Streetcar tracks plunged into the forests and through the stumps of South Vancouver and Point Grey, anticipating the arrival of new housing. Before the arrival of the automobile, these various forms of transportation — foot, hoof, electricity-powered streetcar, and bicycles, too — shared the streets in a way that blends the orderly and the chaotic, as can be seen in this 1907 film taken from the front of a streetcar in Vancouver, filmed by United States filmmaker (and victim of the Titanic sinking) William Harbeck.

Where you live and where you work is shaped by the dominant infrastructure of the day. Consider how your town’s transportation history can be seen in the size and shape of its streets and how the physical space in which you move is, itself, a historic document.

Key Points

- Urbanization in the period before the 1920s was a diverse and uneven process.

- Two major cities — Montreal and Toronto — emerged that would dwarf all others; the growth and economic health of both was based on industrial economies.

- New cities in the West were challenging the lead held by Central and Eastern Canadian cities.

- Cities increasingly developed sections exclusively occupied by higher or lower social classes, in which conditions were very different.

Media Attributions

- Pretoria Day 1901 Celebrations © James Salmon is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Hogenson House © Cocopie on Wikipedia is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Renfrew Textiles Limited Factory © Harry Hinchley, Library and Archives Canada (PA-100649) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Houses for Mr. Meredith, Montreal, QC, 1903 © William Notman & Son, McCord Museum (II-146359) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- City Market, Saint John, New Brunswick adapted by McCord Museum (X13436) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Britannia Mining and Smelting Co.’s Mine © Dr. A.W. Wilson, Canada Dept. of Mines and Technical Surveys, Library and Archives Canada (PA-013798) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Montreal from Street Railway Power House chimney, QC, 1896 © William Notman & Son, McCord Museum (VIEW-2942) is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Calgary from the Elbow River on the Canadian Pacific Railway © William Notman & Son, Library and Archives Canada (C-017804) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Tramway crossing under construction, Ste. Catherine and St. Lawrence St., Montreal, QC, 1893 © William Notman & Son, McCord Museum (II-102021) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Breakneck Steps, Quebec City, QC, c. 1870 © James George Parks, McCord Museum (MP-0000.307.2) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- A boy and horse on Hastings Street near Carrall Street © Major James Skitt Matthews, City of Vancouver Archives (Str P175) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Statistics Canada, Historical Statistics of Canada, 2nd ed., ed. F. H. Leacy (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 1983): A78-93. ↵

- ibid., D1-7 ↵

- Statistics Canada, Census of Canada, 1931, vol.1, Table 13 (Ottawa: 1932). ↵

- Max Foran with Edward Cavell, Calgary: An Illustrated History (Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, 1978), 70. ↵

- L.D. McCann, “The Mercantile-Industrial Transition in the Metals Towns of Pictou Country, 1857-1931,” in Cities and Urbanization: Canadian Historical Perspectives, ed. Gilbert A. Stelter (Toronto: Copp Clark Pitman, 1990): 88-9. ↵

- Peter G. Goheen, “Currents of Change in Toronto, 1850-1900,” in The Canadian City: Essays in Urban History, eds. Gilbert A. Stelter and Alan F.J. Artibise (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1979): 63. ↵

- Bryan D. Palmer, Working-Class Experience: Rethinking the History of Canadian Labour, 1800-1991, 2nd ed. (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1992), 115. ↵

- This is not to say that they had no prior history as human settlements. Both were sites of permanent and semi-permanent Aboriginal communities before, during, and after industrialization. ↵

- John Douglas Belshaw, Becoming British Columbia: A Population History (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2009), 180. ↵

- Peter DeLottinville, “Trouble in the Hives of Industry: The Cotton Industry comes to Milltown, New Brunswick, 1879-1892,” in Labour and Working-Class History in Canada: A Reader, eds. David Frank and Gregory S. Kealey (St. John’s: Institute of Social and Economic Research, 1995): 131. ↵

Civic promoters.

Workers who are not tied to a feudal relationship, slavery, or indentured servitude and are able to move from one employer (or location) to another based on the size of pay and the character of the work.

A facility typically funded out of philanthropic/charitable donations that provides housing and food for impoverished citizens with the expectation that they will do work in return. In the 19th century, associated with workhouses for the poor.

In company towns, housing that is owned by the employer and provided to employees. In some cases, residence in tied housing is a condition of employment, which enables the employer to evict strikers during labour disputes.

An outlet owned by an employer, one that sells goods to employees of the same firm. Commonplace in company towns. See also company store.

An outlet owned by an employer, one that sells goods to employees of the same firm. Commonplace in company towns.

Abandoned communities; associated principally with resource extraction — often mining — towns that have a very short lifespan and which close up once the resource is removed or the market disappears.

A community with one major employer and few other employers; one in which most or all services — in some instances including housing and the supply of food — are controlled by the employer. Associated with remote resource extraction communities.