Chapter 4. Politics and Conflict in Victorian and Edwardian Canada

4.6 Canada and Africa

The debate between imperialists and nationalists (surveyed in Section 4.5) came to a head in the late 1890s as Britain lurched into a colonial war in South Africa. This was not Britain’s first conflict in Africa, nor was it Canada’s. The failed Nile Expedition of 1884-85 — often overlooked — set the stage for Canada’s involvement in the turn of the century war, and was one of several crises in Laurier’s tenure.

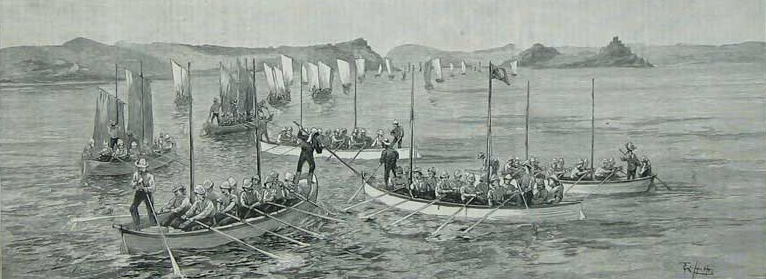

Sudan 1884–85

A botched attempt to evacuate British troops and civilians from the Sudanese city of Khartoum in the winter of 1884 resulted in a year-long siege. Lieutenant-General Garnet Wolseley (1833-1913), an Irish-British career soldier and colonial administrator, was given charge of an expedition to relieve the Britons trapped in Sudan. Wolseley’s connection to Canada was this: He had charge of the Canadian expedition sent to Red River in 1870. In subsequent engagements in West Africa, Wolseley recruited Canadians and other veterans of the Red River invasion to support his efforts. In 1884 — coincidentally, on the eve of the Northwest Rebellion — Wolseley put in another call for Canadian troops, obtaining 390 voyageurs — in actuality, a mix of former fur trade workers, Mohawk from Kahnawà:ke, and loggers from the Ottawa Valley — to assist the movement of more than 5,000 British troops up the Nile. The whole episode was a failure, and Khartoum fell two days before Wolseley’s troops were anywhere near. Moreover, about 200 of the Canadians abandoned their African adventure and hurried home when their six-month contracts expired.[1] Sixteen of their number died on the Nile.

Although this was not a conflict in which Canada declared a direct interest, the Nile Expedition established a post-Confederation precedent: the Dominion’s human resources were available to Britain in wartime. Canada would not be called on again to contribute men to war for another 15 years, but the principle of defending the Empire was in place.

Boer War, 1899–1902

The Second Boer War began in 1899 as the South African Republic and the Orange Free State (colonized by Dutch settlers) resisted British attempts to annex their territories into a larger Cape Colony. Mineral wealth and the goal of a Cape-to-Cairo chain of colonies was what motivated Britain and its agents in South Africa. The origins of the Second Boer War can be traced, also, to the overlap between imperial and capitalist agendas in South Africa. Britain had what it regarded as strategic objectives, and these were funded and driven forward by private plans to exploit mineral, human, and other resources, but specifically diamonds and gold. Two colonies — the South African Republic (aka: Transvaal) and the Orange Free State — stood in the way. These were colonies left over from the days of the Dutch East India Company’s activities at the southern tip of the continent, and they had long been in conflict with British forces. They were, moreover, hardened by their experience of persecution by neighbours and their conflict with the region’s Indigenous peoples in the so-called Zulu Wars. These trials, along with their migration into the interior of South Africa, contributed to a strong sense of Boer Trekker (or Voortrekker) community identity and a sharpened and highly conservative religious culture.[2] The Boers were not wealthy, nor were they particularly close — physically or diplomatically — to the coastal Afrikaners (other descendants of the Dutch colonial experiment). To private British interests in the region they seemed ripe for the picking and efforts were made to stir up a Boer rebellion that would necessitate an official and armed British relief effort and then a conquest. This failed, so the British opted for less subtle means and war was declared in October 1899.

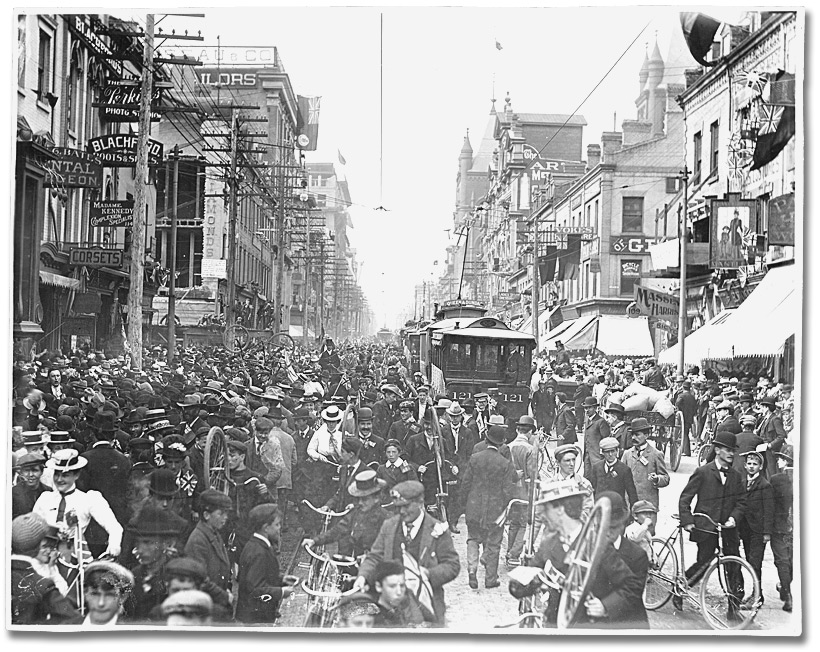

Canadian involvement began with 1,000 volunteers under the command of Lieutenant Colonel William Otter, who had (poorly) led the Canadian Permanent Force against the Métis and the Cree in 1885. Enthusiasm among English-Canadians, however, was so great that a further 6,000 recruits were easily obtained. This was (with the exception of a regiment of Constabulary) a one-year commitment for recruits — time enough to sail across the Atlantic and spend a Canadian winter in sunnier climates while fighting for the honour of the Empire. Recruits were paid, public donations poured in to insure their lives and protect their wives and children from penniless widowhood and orphanhood, and a whole contingent — the Strathcona Horse — was assembled and paid for by Donald Smith (now Lord Strathcona), the former CEO of the Hudson’s Bay Company, Conservative MP, and driving force behind the Canadian Pacific Railway.

The course of the war was nothing glorious, despite initial excitement among imperialists. Britain’s military strategies were transparently ineffective, the Boers were better armed, better prepared, and better motivated than expected and much more so than they had been in the First Boer War. 1899 ended on a low note as the tempo changed to a grinding guerrilla defence running up against a steady, if plodding, march on the capitals, Pretoria and Bloemfontein. It was in this phase that the British began to deploy concentration camps and engaged in a scorched-earth policy that targeted Boer farms. At Paardeberg Drift in February 1900, two Canadian units from the Maritimes wore down a much larger Boer force and secured a badly needed victory for the Empire. The Canadians distinguished themselves individually, but Paardeberg was otherwise their high-water mark in the war. And while medals were handed out (including four Victoria Crosses) and the troops were feted on their return, there was also a crack opening in the Canadian imperialist armour.[3]

This was the Dominion’s first international (as opposed to cross-border) conflict and it was transformative. Imperialist sentiment was such that Canadian troops and officers initially deferred to British commanders, whose performance subsequently proved to be worthy of reproach. Returning soldiers complained about British class snobbery and incompetence in the field. Now, complaining is something that soldiers are wont to do, but in the particular context of Edwardian Canada, this did less to subtract from loyalty to Britain than it did to add to an embryonic English-Canadian national sensibility. It reinforced a growing sense that, as a part of the Empire, Canada ought to be treated less as a subordinate and more as an equal. (In this there are echoes of the contemporaneous Provincial Rights Movement that sought to erase the belief that Ottawa was superior to the provinces.)

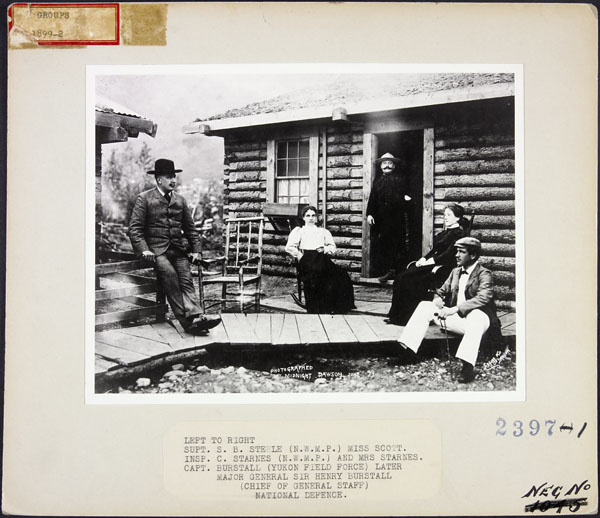

The Boer War left several other legacies. It cemented the already near-mythical reputation of Sam Steele (1848-1919). A militiaman who fought Fenians in 1866, a member of Canada’s first regular army unit, one of the earliest members of the NWMP, a veteran of 1885 (he fought the Cree at Frenchman’s Butte and Loon Lake), a Mountie in the East Kootenays and also in the Yukon during the Klondike gold rush, Steele was placed in charge of the Strathcona’s Horse Regiment at the ripe age of 50. Steele served as a model of masculinity for a generation of Canadians, and as a symbol of Canada’s maturing strength as a nation.

The South African conflict also led Canadians to think that international wars might be relatively short with tolerable casualties. In two and a half years of combat there were only about 250 Canadian casualties from 7,000 troops, and it is reckoned that more than half of these died from disease, not battle wounds. (At worst this mortality rate was a third of what would be recorded in the Great War.) When August 1914 rolled around, then, it was South Africa that Canadians remembered, and not the much more comparable (and vastly more damaging) Napoleonic Wars a century earlier.

Canada’s Century

In the midst of the Boer War, Laurier realized that he needed to be able to galvanize nationalists and imperialists alike and not just keep them from one another’s throats. In 1905 he told the House that “as the 19th century had been the century of the United States, so the 20th century would be the century of Canada.”[4] This was a sentiment both sides could embrace, but only, of course, if Laurier could stop the country from imploding.

South Africa drove deeper the wedge that existed between English-Canadians and French-Canadians. It also served to alienate from the Anglo-Canadian vision of Canada many of the immigrant communities that identified more with the Boers than with the British forces.

Nationalistes were opposed for two main reasons: they argued that Canada ought not to be sucked into Britain’s imperial vortex and that the situation of the Boers was not entirely unlike that of the French-Canadians. Indeed, there were echoes of the Northwest Rebellion: Not only was an agrarian, non-anglophone population caught squarely in the gun sights, but the very same personnel were holding the rifles. The Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry sent to South Africa was under the command once again of William Otter and the mounted regiment was led by the ubiquitous Colonel Steele. By contrast, imperialists viewed Canadian involvement in the Boer War as a matter of duty and also as an opportunity to demonstrate the growing maturity and capacity of the Dominion.

Laurier’s instincts were always to find a compromise, and they were never better illustrated than in 1899. Refusing to support a deployment of regulars, which would have sent French-Canadians into battle against the Boers, he opted to muster a corps of volunteers. At first this was only a force of 1,000, but it grew eventually to 7,000. Anglophone imperialists were offended by the smallness of Canada’s engagement, especially at the start; francophones opposed to the war rioted for three days. Laurier faced several poor options, and his compromise was less divisive than any of the other choices open to him. If elections are the final litmus test, the opportunity for voters to turn on him came in 1904 and he survived.

Key Points

- By 1900 Canada had been involved in two military expeditions at home and two abroad.

- The two campaigns in Africa — Sudan in 1884-85 and the Second Boer War — were in support of British imperial goals.

- Both conflicts were small adventures with few casualties, which may have led to Canadians underestimating the seriousness of the Great War when it began in 1914.

- The Boer War was profoundly divisive in domestic politics.

Long Descriptions

Figure 4.15 long description: Three men and two women sit outside of a log cabin. The caption says “Left to right: Superintendent S. B. Steele (N.W.M.P.); Miss Scott; Inspector C. Starnes (N.W.M.P.); and Mrs. Starnes. Captain Burstall (Yukon Field Force), later Major General Sir Henry Burstall (Chief of General Staff) National Defence.” [Return to Figure 4.15]

Media Attributions

- The Nile Expedition for the Relief of General Gordon © The Graphic magazine is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Midnight in the Yukon, June 1899 © Library and Archives Canada (MIKAN no. 3710400) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Pretoria Day, June 5, 1901 © Archives of Ontario, I0006399 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Sir Wilfrid Laurier speaking from the platform of a railway observation car during the federal election campaign © Library and Archives Canada (C-002616) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- O. A. Cooke, “WOLSELEY, GARNET JOSEPH, 1st Viscount WOLSELEY”, in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed 21 August 2015, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/wolseley_garnet_joseph_14E.html. ↵

- The terminology used to describe the Dutch settlers of South Africa is complicated and often misleading. Some of them were French Huguenots and not Dutch at all. The settlers most closely connected with the Dutch Company’s forts and harbours are historically more likely to be described as Afrikaners, and the rural populations as Boers (Dutch for farmers). The whole of this population is linked by the use of Afrikaans, a dialect comprised largely of Dutch but also Indonesian and African elements. The Boer resistance to the British stemmed in part from their decades-long effort to avoid British rule by migrating north and inland. The Voortrekkers’ self-imposed exile hardened their attitude towards both the British and the coastal Afrikaners, some of whom joined in the War on the side of the British. One can easily find in this story elements of the Métis situation 15 years earlier, insofar as the former Red River Colony was largely abandoned to the Canadians and the Métis forced off into the interior where they were significantly less well off and running out of places to hide from imperial forces. ↵

- The most comprehensive source on this topic is Carman Miller, Painting the Map Red: Canada and the South African War, 1899-1902 (Montreal & Kingston: Canadian War Museum & McGill-Queen's University Press, 1993). ↵

- Canada. House of Commons, Debates, 21 February 1905. ↵