Chapter 5. Immigration and the Immigrant Experience

5.11 Post-War Immigration

When it comes to immigration, the century can be divided in two along the fulcrum of WWII. Prior to the war, immigration was principally understood within the context of building an agricultural colossus and assembling an army of workers to tear down forests and wrest ore from the belly of the Earth. And it took place within the context of a kind of cultural sensitivity that was mostly alert to anything that would challenge the dominance of Anglo-Celtic Protestant and Franco-Catholic “founding nations.” It was for this reason that Buddhist, Shinto, Sikh, Muslim, and Jewish immigrants in particular – alike in that none were Christian – were especially marginalized. The cataclysms of 1939-45 changed both circumstances and minds.

Post-War Refugees

After 1945 Europe opened its floodgates as hundreds of thousands sought refuge from a devastated continent. British emigrants were fleeing cities destroyed by the Blitz and diets stunted by rationing; there were, too, 41,000 war brides and nearly 20,000 children fathered by Canadian soldiers stationed in the UK during the war. Refugees poured out of Germany, especially in the wake of the quartering of the nation (and Berlin) into Soviet and Western zones (see Section 9.4). The same was true of Czecho-Slovaks uncertain of their country’s future and disconsolate about its immediate past. In Italy, Austria, France, the Netherlands, and Belgium refugee camps were established in the late 1940s. Called DP Camps — for Displaced Persons — these were the focal point of efforts to sort the human chaos into emigrant streams. (Immigrants in this wave were casually, sometimes derisively, referred to as DPs regardless of whether they had endured the camps.)

Canadians played an important role in both the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) and the International Refugee Organization that succeeded it in 1947. Ottawa was committed to accepting significant numbers of able-bodied refugees, although Canadian anti-Semitism continued to throw up obstacles to Jewish refugees and survivors of death camps. As the Cold War got underway, anti-Communist applicants were favoured over others: Poles and Ukrainians together represented 39% of the 165,000 in this refugee wave, followed by Germans and Austrians (11%), Jews (10%), and smaller measures of Baltic and Central European emigrants. One historical study of this migration by Franca Iacovetta points to the role of Canadian “gatekeepers” who processed applicants in what she describes as “a worldwide labour relocation program.”[1] There were many ironies and tragedies in this process, possibly the most outstanding being that anti-fascist resistance fighters were often viewed by Canadian authorities as insufficiently anti-Soviet and they were, for that reason, less likely to be allowed into the country. This was notably the case among Jewish refugees whose animosity toward the fascists was understandably greater than their hostility toward communism.

Barely had the immediate post-war exodus tapered off in 1953 when new Cold War migrations got underway. In November 1956, as Soviet tanks rolled across a rebellious Hungary, 30,000 of some 200,000 exiles fled to Canada. There was a humanitarian agenda here, to be sure, but it is also important to note that providing sanctuary and opportunity to Soviet-bloc Europeans during the Cold War had propaganda value as well. And it cut two ways: their successful integration into a prosperous postwar Canadian democratic order taunted those who remained behind and, at the same time, anti-communist refugees spread a message among Canadians of Soviet oppression and terror.

The first waves of Cold War–era immigration from Europe were followed in the 1950s and 1960s by family reunification arrivals. As siblings and other relatives found their way to Canada, the majority made their way to urban Ontario. Diversity existed there before WWII but in the 1960s it became transformative. The established British-Canadianism of Toronto and Hamilton was itself being reduced to enclaves of what former Prime Minister Stephen Harper once described approvingly as “old stock” Canadians.

Ideological turmoil had consequences for Asian immigrants as well. Liberalization of attitudes toward Chinese immigration began in 1947, in large measure because China had been a target of Japan (an enemy of the Allied forces during World War II). Chinese Canadians were quick to volunteer for service in the Canadian Army in wartime and, after official barriers were dropped, they joined the Navy and Air Force as well, all of which contributed to a change in attitude in White society. In 1947, then, the 1923 Immigration Act was repealed and it became possible for Chinese immigrants and their descendants to obtain Canadian citizenship. Four hundred did so that year in a mass ceremony in Vancouver.[2]

The timing of the policy change, however, was poor. In 1949 the Chinese Revolution brought Mao Zedong (aka: Mao Tse-tung) and his Communist Party to power in Beijing. Almost immediately barriers to emigration were erected and once again Chinese (outside of Hong Kong and Taiwan) were unable to join members of the diaspora.[3] Emigration from Hong Kong would continue, however, and it accelerated in the 1980s as Britain reluctantly prepared to hand over control of the colony to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1997. Large numbers of (mostly wealthy) Chinese made their way to Canada at this time, establishing a significant enclave in Richmond, BC, and appearing in most major cities. Changes within the PRC and a growing economy enabled “mainlanders” to emigrate as well, and by the first decade of the new century the Chinese community in Canada had become vastly more complex, consisting of old families – some of which had roots in Canada going back to the 1850s, most of whom had originated in Guangdong, and the majority enjoying modest incomes while still strongly oriented toward community institutions in Chinatowns – contrasting with wealthy and super-wealthy recent arrivals from Hong Kong and the PRC, a great many of whom spoke Mandarin (Putonghua) rather than Cantonese (Guangdong speech) and almost none of whom regarded Chinatown as representative of their history, experience, and aspirations. (For more on this topic, see Section 5.12.)

Post-Centennial Immigration

The centennial year marked a further change in immigration policy. Up to this time, Ottawa preferred settlers from the British Isles, the United States, and Western Europe. In 1967 the government introduced a points system. Under this regime applicants were given preference if they knew either (or both) French or English, were non-dependent adults (that is, not too old to work), had jobs lined up already in Canada, had relatives in the country (to whom they might turn for support), were interested in settling in parts of the country with the greatest need for workers, and were trained or educated in fields that were in demand. The economy was still expanding and in some regions it would continue to do so for many years. Canadians have not always demonstrated sufficient mobility to fill the hiring needs of some regions, nor to fill some economic niches (especially what are often called “entry-level jobs”). Under these circumstances the new legislation was to prove key in attracting large numbers of new Canadians from sources that were considered “non-traditional”.

In the 1970s, Montreal was no longer Canada’s largest metropolis, the increasingly multicultural Toronto having shot past its downriver rival. This was only the most easily observed demographic change. Proportionally greater transformations were seen in cities like Vaughan, ON. Located north of Toronto, Vaughan was a small town until the late 20th century, when it leapt from fewer than 16,000 in 1961 to 182,000 in 2001 (and it has nearly doubled since then). Most of that growth came from Italian and Jewish post-WWII immigration which, combined with immigrants from other sources, made it one of the fastest growing centres in Canada: the English Canadian population in Vaughan is, as a consequence, almost insignificantly small. Similar patterns can be seen in suburban settings like Vancouver’s Richmond and Surrey, where growth rates have outstripped all other centres in Canada in the last decade or more.

Some rural areas enjoyed growth spurts in the post-WWII period. In the 1960s young American men and women fled to Canada to avoid being drafted into the United States Army for duty in the Vietnam War. Especially large nodes were established in British Columbia’s Kootenays, in the Gulf Islands, and along the Sunshine Coast. Others followed, including counter culture, back-to-the-land advocates who were more pulled than pushed into Canada (see Section 9.16). At around the same time, Indo-Canadians coupled suburban living with exurban and rural agriculture, becoming a dominant feature in British Columbia’s farming sector. Hispanic immigrants followed a similar trajectory, particularly in regions that were linked with strong farming settlements immediately south of the border.

African Immigrants

The numbers of Canadians from Africa has been growing rapidly since the 1990s. Urban areas see considerable concentrations drawn from many parts of Africa. One study on the African diaspora in Vancouver indicates that these immigrants consistently experience downward social mobility because their education and skills are often not recognized or valued in Canada. Many are drawn from professional and semi-professional careers in Africa only to find that they must pursue very low status and vulnerable jobs. Access to free farmland is not an option available to this generation of new arrivals nor, because of the diverse sources of African immigration, are social agencies comparable to the Chinese Benevolent Association. Somalians and Nigerians, Sudanese and Mozambicans lack the common set of cultural, political, and economic interests and inclinations to establish what was possible among the more cohesive Guangdonese and Punjabi immigrant communities 100 years ago.[4]

Toward a Cultural Mosaic

Although Canadian society has long been composed of diverse elements, the “two founding nations” narrative prescribed absorption, assimilation, and exclusion as strategies for managing newcomers. The idea of a cultural mosaic — as opposed to the American melting pot — would have been anathema to most English and French Canadians before the 1960s. Several developments produced a more inclusive society.

The first of these was purely demographic. Large numbers of Laurier-era immigrants had large numbers of children; immigrant fertility – especially in rural areas – was high. That meant that by 1960 there were at least two generations of growing numbers of what Conservative Prime Minister John Diefenbaker called “hyphenated Canadians.” Some were finding their way into post-secondary education – pioneers in their families in this respect – and were critical of narratives they encountered that privileged French and English Canadians. Additionally, incompletely assimilated urban and rural communities now represented significant voting blocks and they could not be treated with condescension by hopeful politicians. The Liberal Party, in particular, was well positioned to take advantage of these changes and did so. Diefenbaker (whose career is surveyed in Section 9.6) occupies an ironic position in this story: a German Canadian, he was critical of “hyphenation”, seeing it as a kind of second-class status. So, while he might decry special privileges to any minorities because it served to perpetuate that minority status, a growing chorus of Liberal Party voices called for more pluralism. As the party that was most likely in office when post-WWII immigrant families first arrived, the Liberals reaped some benefits at the polls in gratitude. The first Chinese Canadian candidates were Liberals and the party prominently ran Italian and Portuguese Canadian candidates as well.

The changes to the Immigration Act in 1967 produced waves of arrivals from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. The vast majority of these New Canadians headed to the urban centres, especially the largest five or six cities. After 1971, despite much higher fertility rates in rural Canada, cities continued to grow at a more rapid rate, mostly from new immigration. Typically, newcomers gravitated towards lower-income neighbourhoods where rents were cheap and familiar foods might be obtained. A recent study calls these immigrant nodes within metropolitan areas “arrival cities,” landing pads for migrants who, since the 1960s, have been coming by air and not by sea or rail.[5] These immigrants further reinforced the advantages enjoyed by the Liberal Party.

By the 1960s there had occurred, too, a change in popular attitudes. The Nazi war crime trials in the late 1940 that revealed the extent of the Jewish holocaust under the Hitler regime proved to be a turning point and spurred efforts to develop language around human rights. Full citizenship for many groups, however, only came into reach slowly; Asians, for example, got the vote in the 1960s (as did some Aboriginal people). At about the same time – in the early- to mid-1960s – we see the beginnings of official multiculturalism and inclusivity. The 1963 Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism didn’t issue a report until 1969 but its mandate and early claims for the precedence of English and French in Canada catalyzed a reaction among “Third Force” Canadians – Canadians whose ancestry was neither French nor English.

Espousing a new inclusivity was both a political strategy for election day and a way of breaking with the old “duality” of Confederation. The Liberals under Pierre Trudeau were simultaneously building a bilingual and bicultural society while rolling back assimilative requirements for immigrants. Rather than divide the growing immigrant demographic along ideological lines, they reasoned, it might be held together as a Liberal block if its own (various) values were respected. As early as 1969, Trudeau was quoted saying, “For the past 150 years nationalism has been a retrograde idea. By an historic accident Canada has found itself approximately 75 years ahead of the rest of the world in the formation of a multinational state.” Practices and rhetoric in the 1970s increasingly reflected these values, and was manifest in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms of 1982. This movement culminated in the Multiculturalism Act of 1988.

None of these changes erased the reality of bias and prejudices that confronts immigrants, but they did created a legal framework in which discrimination might be challenged. Two such challenges came from the Asian community in British Columbia in the 1980s. While Eastern European immigrants to the Prairie West experienced xenophobia and disadvantage in the 20th century, they were not taxed on entry in an attempt to both control their numbers and to generate government revenue. This, of course, was the experience of Chinese immigrants under the Head Tax regime.[6] Nor were any European, American, or African immigrants confronted with special legislation to stop the arrival of their family members and to deter further immigration from their ancestral homeland. This, too, was the experience of the Chinese community under the federal Chinese Immigration Act (also called the Chinese Exclusion Act) of 1923. And although it is true that some German, Ukrainian, Bulgarian, Turkish, and Italian Canadians were interned as enemies of the state during the two World Wars, these were predominantly select individuals who were outspoken supporters of enemy regimes and very few of them suffered extensive or permanent loss of personal property; nor did these internments constitute a community-wide, round-up based on ethnicity alone. For the Japanese Canadians in World War II, the situation was starkly different: property was confiscated, auctioned off, and never returned. The entire community, including infants and the elderly, was captured and incarcerated in camps for the duration of the war with Japan; the end of internment brought further barriers to reintegration and the prospect of deportation to Japan (see Section 6.17). Because of these significant, not to say monumental, differences in the experiences of the Japanese and Chinese communities, apologies and compensation were sought from various levels of government from the 1980s on.

Successive Quebec governments dealt with the issue of multiculturalism differently. Fearing that the majority of immigrants would gravitate towards or even demand schooling in English for their children, the provincial government took steps in the 1960s-1980s to close off that avenue. While a disproportionate share of immigrants to Canada from former French colonies chose to settle in Quebec (especially Montreal), there were also large numbers of immigrants who spoke neither English nor French. These newcomers – described as allophones – were a significant demographic and were courted by both the Liberals and the Parti Québécois, especially during the referendums on Quebec sovereignty. (See Sections 9.11 and 12.3 for more on this topic.)

Key Points

- Post-WWII immigration included refugees from war-ravaged Europe and from communist regimes in Eastern Europe.

- New sources of immigrants were being increasingly tapped, and greater numbers were heading to cities than to the countryside.

- After 1967 much of the focus of new immigration was in suburban centres.

- The increased diversity of the Canadian population created political opportunities; politicians seized on ideals like multiculturalism and recognized long-standing ethnic community grievances.

Media Attributions

- Immigration interpreter aids Hungarian refugee © Canada Dept. of Manpower and Immigration, Library and Archives Canada (PA-181009) No restrictions on use.

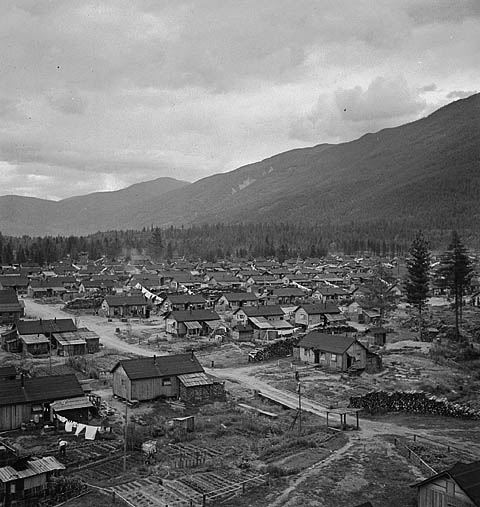

- Internment camp for Japanese Canadians © Jack Long, National Film Board of Canada. Photothèque, Library and Archives Canada (PA-142853) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Franca Iacovetta, Gatekeepers: Reshaping Immigrant Lives in Cold War Canada (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2006), 3-5. ↵

- Timothy J. Stanley, Contesting White Supremacy: School Segregation, Anti-Racism, and the Making of Chinese Canadians (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2011). ↵

- Wing Chung Ng, The Chinese in Vancouver, 1945-80: The Pursuit of Identity and Power (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1999). ↵

- Gillian Crease, The New African Diaspora in Vancouver: Immigration, Exclusion, and Belonging (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011), 17. ↵

- Doug Saunders, Arrival City: The Final Migration and Our Next World (Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2011). ↵

- Lisa Rose Mar, Brokering Belonging: Chinese in Canada’s Exclusion Era, 1885-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010). ↵

At the end of both World Wars, European women — principally British — who married Canadian servicemen and relocated to Canada when their husbands returned home.

Peoples (principally in Europe) dislocated by World War II; refugees.

A challenge to mainstream culture posed by a group’s rejection of dominant values. In the 1960s youth movements and specifically the hippy movement constituted a counter cultural moment.

Refers to residential lands that lay beyond the suburban fringe.

In contrast to the concept of a “melting pot,” refers to a multi-ethnic and multicultural society in which differences are permitted to continue, rather than face assimilation into a single typology.

In contrast to dualism, supports the concept of a community or state made of diverse parts, particularly as regards aspects like ethnicity, creed, and/or language.

Term used since the late 1960s to describe recent immigrants, particularly those arriving from non-traditional sources like South Asia, Latin America, and Africa.

Internationally-convened trials to address allegations of crimes against humanity including (but not limited to) murder of civilian populations and enslavement.

The campaign launched in the 1930s and early 1940s by the German National Socialist government aimed at the eradication of the Jewish population in Europe. Estimates of the number killed run to 6 million or more.

Any right thought to belong to every person. Enshrined in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1947.

A person whose first language is neither French nor English.