Chapter 5. Immigration and the Immigrant Experience

5.4. The Clifford Sifton Years, 1896–1905

Among the most able and imaginative of Laurier’s cabinet ministers was Clifford Sifton (1861-1929). Born in southern Ontario, Sifton entered adulthood in Manitoba where he established himself as a lawyer, entrepreneur, and politician. Under Laurier he was Minister of the Interior, which put him at the helm of Canada’s evolving immigration policy.

In the 30 years after the BNA Act was proclaimed the population of the West increased at a rate that was unmatched in the history of British North America. From a few thousand around Red River and similar numbers across what would become Alberta and Saskatchewan in 1905, the North-West Territories (that is, the Prairies beyond little Manitoba) surpassed 56,000 by 1881. Ten years later, this had nearly doubled to 99,000. In 1896, therefore, Sifton inherited a portfolio that was already doing well, though not as well as it might.

The Victorian Food Revolution

Mechanized farming, new crops, new transportation technologies that cut the time and distance between harvest and market, and the need to feed burgeoning urban populations were together revolutionizing farming on a global level. Over the course of the 18th and 19th centuries central Europe had become a complex patchwork quilt of ethnic, farming enclaves. Germanic settlers moved into the Ukraine, and minority religious sects — often associated with pacifism — established farming communities with strong cooperative sensibilities. Some had reasonably deep roots but much of the lands between the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea were farming frontiers in their own right. Similarly, agricultural lands were opening in Argentina on the Pampas, in Australia, and across southern Africa. In the United States three million families were drawn into the American West by the promise of homesteads. This was a global phenomenon and — as the Indigenous populations were being removed by the colonial regimes — settlers were being recruited into various farming colonies with an assortment of promises and assurances. In short, the business of finding farmers was competitive.

Sifton’s timing was good. The American frontier — as the United States historian Frederick Jackson Turner announced in the 1890s — was “closed”: free land in the United States was all but gone. Sifton replied with a campaign to bill the Canadian Prairies, famously, as “The Last Best West.” Employing a variety of sales and advertising strategies and gimmicks that were startlingly innovative, Sifton and his department changed the face of Canada in the space of one decade.

Selecting Prairie Society

Sifton established a list of preferred sources for immigrants. This is interesting for a few reasons, which are worth enumerating. First, the outcome of his preferential list can be seen even now in the ethno-linguistic and cultural make-up of the Prairie West. Second, it reveals contemporary thinking about the nature of race and ethnicity. Sifton, like most of his peers, believed that ethnicity signalled essentialized qualities: that is, all Italians were, in their essence or fabric, the same. Stereotyping, then, was something he regarded as part of informed decision-making, not a case of narrow-mindedness or bigotry. Third, the composition of the immigrant pool included people whose ethnic differentness from Anglo-Protestants and Franco-Catholics (not to mention Aboriginal peoples) were in some instances profound, and that very differentness created a perceived need to build institutions and policies that would foster their assimilation. As Prairie settlers they might reasonably have been assimilated into the bilingual and bi- or multicultural heritage of the Métis; they might have been assimilated into a new, bicultural French and English Canada. Steps were taken, however, to transform these new arrivals into anglophones. And this would prove profoundly divisive among Central Canadians who were, predictably, not in agreement on the privileging of Anglo-Protestantism over Franco-Catholicism.

So who did Sifton prefer? White Americans, mostly. People who had had experience homesteading and who spoke English (and who were likely Protestants) were the principal group he hoped to recruit. Of course, Americans brought with them the possibility of disloyalty, something which made Canadian politicians generally wary. But even the Macdonald regime (more than a little America-phobic) had circulated recruitment materials in the United States, mostly in the hope of finding Canadian emigrants who could be lured back “home” to the West. Almost one million people arrived in Canada from the United States in the 14 years leading to the Great War, and many of those immigrants were, in fact, returning Canadians. Many more were German and Scandinavian immigrants to the United States who simply kept moving until they landed in the Canadian West.

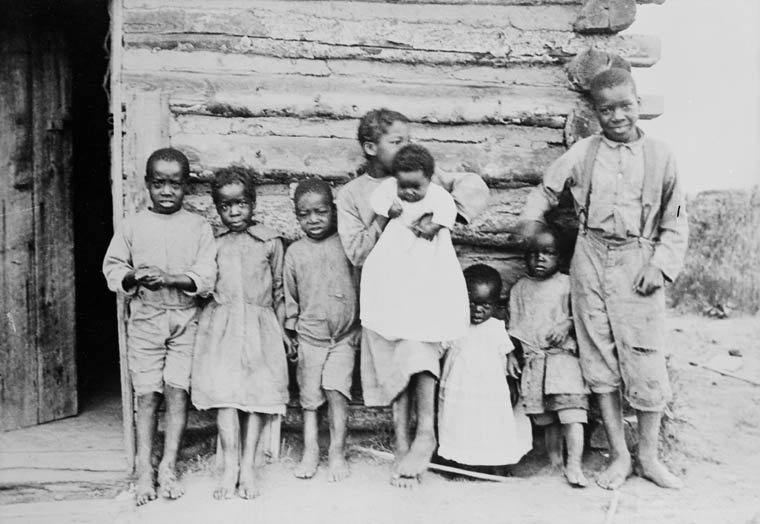

African-Americans, among whose numbers there were many with homesteading experience, were desirous of coming to Canada but Sifton regarded Africans and people of African descent dimly. He was inclined at first to recruit from the British Isles but recognized quickly that mixed-farming on small-holdings in the United Kingdom was a far cry from producing wheat on a quarter-section of land on the Prairies, and Sifton knew, too, that British recruiters would trawl the under-employed urban populations first. He turned his attention to continental options.

German farmers had proven their skill in various settlement projects that had occurred since the 18th century. For 100 years and more, the German states had been sending out farmers to populate borderlands in places across the Austro-Hungarian Empire and as far east as Imperial Russia. Sifton thought highly of the Germans and the Scandinavians. But the further south in Europe he turned, the less impressed he became. Italians and Greeks, in particular, he thought of as worthless to the settlement process. Jews were also to be avoided, as were Arabs.

Eastern Europeans — Ukrainians, Poles, and Russians fared better in Sifton’s eyes. In an oft-quoted statement, the western booster described what he saw as the ideal immigrant:

When I speak of quality I have in mind something that is quite different from what is in the mind of the average writer or speaker upon the question of immigration. I think that a stalwart peasant in a sheepskin coat, born to the soil, whose forefathers have been farmers for ten generations, with a stout wife and a half-dozen children, is good quality.[1]

Sifton made this statement in 1922, 17 years after resigning his cabinet post and looking back on his works in retrospect. From 1896-1905, however, immigrants from Eastern Europe were something of an unknown commodity. And, for a cabinet minister in a narrow-minded Protestant community, they were a bit of a gamble. The Eastern Europeans’ arrival in bulk numbers, their enthusiasm for mutually-supportive block settlements, and their overall record of success, however, converted Sifton to their value.

Sifton was likewise convinced that religious sects that had strong internal cohesion and familiarity with the kind of farming that would be conducted in the West were highly desirable. These included Mormons from the United States, Mennonites from Central and Eastern Europe, and pacifist Hutterites and Doukhobors from Russia. Ethnicity, experience, and the likelihood of community success thus became key principles of the recruitment process.

Against this list of preferences, Sifton was highly suspicious of urban and industrial workers. In an era where “modern” was acquiring a cachet all its own and in which civic growth — even that of Sifton’s beloved Winnipeg — was a principal measure of success, there is something very 18th century about Sifton’s 20th century vision.

Sifton the Salesman

Sifton recognized early on that simply putting up posters at shipping offices in Hamburg and Liverpool would not draw the numbers he required. So in 1899 he established a network of recruiting agents in Europe under the auspices of a shadow corporation called the North Atlantic Trading Company. Shipping agents in European ports were paid to direct farm emigrants toward Canadian ports. This was a clandestine operation in part because the European countries targeted were all trying to stop the bleeding off of their population to new settlement societies like Canada, the United States, Argentina, and Australia. Sifton’s strategy paid off: in the space of a decade, the Prairie population more than doubled to 211,649 by 1901 — the greatest part of that growth taking place after the Laurier government arrived in Ottawa in 1896.

Diversity was, as a consequence of these recruitment efforts, growing rapidly in the West and in some Atlantic port towns. It was politically imperative that English Canadians be reassured that their culture was not at risk. To that end, Sifton stepped up efforts to recruit from Britain in 1903. The results were significant: 1,200 arrived in Canada in 1900 and 65,000 in 1905. This was not, however, a typically agrarian population. This Edwardian-era wave was made up of professionals, merchants, urban labourers, mineworkers, and others whose conditions in a rapidly growing and changing country were in some jeopardy. Canada was presented to them as Brit-friendly, “just like home,” and an opportunity to enjoy real social mobility — something that the entrenched class system in Britain stifled at best and prevented at worst. It was this generation that repopulated the Okanagan Valley and southwestern Alberta, with visions of becoming “gentleman orchardists” and ranchers. It was also this generation that supplied many of the early trade union leaders and members whose experience with Britain’s new-born Labour Party would produce echoes across Canada and especially in British Columbia. On Vancouver Island, British immigrants would cultivate two contrary myths of British-ness characterized by both an ersatz upper-class Britophilia in Victoria and British-style labour militance in the coal mining towns of Nanaimo, Wellington, Ladysmith, and Cumberland. Both of these movements overlay existing Island political and social traditions so deeply that they effectively eclipsed them to the point that Britishness became part of the Vancouver Island brand.

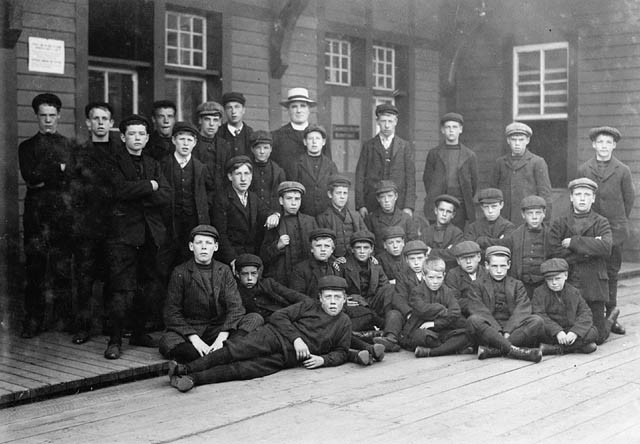

However much the British immigrants of the pre-Great War years played a role in reaffirming imperial connections and the primacy of Anglo-Protestantism, they were not always welcomed by the locals. Canadians were often irritated by British sensibilities and signs appeared in shop windows across the country, “No English Need Apply.” There was a sense, too, that many of the British immigrants were simply impoverished social detritus, incapable of functioning in their own society let alone in Canada. Tens of thousands of children — part of a migration referred to as the Home Children — were plucked from British slums and orphanages and placed into apprentice-like situations on Canadian farms. Scandals and outrages plagued the Home Children project as news leaked out from time to time of horrible physical abuse and neglect of the 8 to 10 year old immigrants. It was, however, the failure of the Barr Colony project, an attempt to settle British farmers in a Prairie block, that drew the greatest criticism of Sifton’s office and further confirmed the Canadian belief that British immigrants made for poor farmers.[2]

Post-1905

Sifton resigned from the Laurier government early in 1905, seemingly at the top of his game. The recurrent issue of sectarian, French-language schooling and the cultural agenda in the West was his last round-up. The North-West Territories had enjoyed non-denominational schools under the territorial regulations of 1901. This was slated to come to an end with the arrival of provincial status for Alberta and Saskatchewan and the extension of guarantees of separate and state-funded schools for Catholics. Laurier, who cautiously promoted the ideal of dualism in the West, would not give way and Sifton — who preferred the vision of an Anglo-Protestant West — resigned. Later, Laurier found himself obliged to change course, but Sifton did not re-enter the cabinet.

In many respects, Sifton was not only an architect of Western Canada: he was an example of what it was becoming. A relentless booster of Winnipeg and Brandon, he was an advocate of social reforms (his wife, Elizabeth Burrows, led the Brandon Women’s Christian Temperance Union), and a champion of non-denominational schools in the West (often used as coded-language for anti-French or anti-Catholic education). The society he envisioned in 1896 was not one that all Canadians at the time embraced: drawn from different and diverse locales, peoples of many languages and cultures would open the economic potential of the West and, thus, Canada. In return, they would be Anglo-Canadianized and offered what Dominion officials immodestly regarded as a superior and more humane cultural alternative to that of the United States. Although many factors independent of Sifton contributed to what was to follow, the fact remains that many aspects of his vision were realized.

Key Points

- The late 19th century saw a rapid expansion in global food production to feed industrializing communities and nations. Canada’s expansion into the West was part of this process.

- Canada had to compete for immigrants and did so through strategies that targeted specific groups and whole communities.

- Clifford Sifton’s term as Minister of the Interior coincides with the largest waves of immigrants to the West and thus gave shape to the population that arrived around the turn of the century.

- Sifton’s preferences as regards immigrant groups were explicitly in favour of northern Europeans over southern Europeans, Whites over non-Whites, and people with experience farming in prairie-like conditions.

- Concerns among British-Canadians that their culture might be under threat was met by new recruitment of British immigrants in the early 20th century.

Media Attributions

- Doukhobor women are shown breaking the prairie sod by pulling a plough themselves © Library and Archives Canada (C-000681) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Black Colony, Athabasca Landing, Alberta © Canada Dept. of Interior, Library and Archives Canada (PA-040745) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Galician immigrants © William James Topley, Library and Archives Canada (PA-010401) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Pear blossoms in Mr. Stirling’s orchard, Kelowna, British Columbia © G.H.E. Hudson is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Immigrant Boys for the St. George’s Home, Hintonburg © Library and Archives Canada (PA-020907) is licensed under a Public Domain license

An initiative in settling the West with groups drawn from the same ethnicity or creed allocated contiguous lands so as to take advantage of cultures of mutual support.

An immigrant group comprised of pacifists belonging to a Russian dissident religious movement. Settled first on the Prairies then mostly relocated to British Columbia. Persecuted in the 20th century for their pacifism and their rejection of material culture.

Over 100,000 children who were exported from Britain to Canada between 1869 and the late 1930s. Organized by charitable church organizations to alleviate overcrowding and to provide improved and more healthy alternatives. Stories of abuse abound, although many of the children who were distributed to farms across Canada did enjoy improved circumstances.

Located west of Saskatoon covering a massive area that extended to and across what would become the Saskatchewan-Alberta border, the colony was populated by some 2,000 immigrants recruited directly from Britain.