Chapter 7. Reform Movements from the 1870s to the 1980s

7.9 Reform Politics: 3rd Parties

The American political system has been demonstrably inhospitable toward third parties for nearly two and a half centuries. The British parliamentary system, however, allows for third parties and more. Admittedly, the first-past-the-post arrangement eats into the likelihood of small party success. (While a party might secure 25% nationally, they might not win enough votes in any one constituency to elect even a single MP.) But the possibility of a breakthrough exists and this has encouraged the rise of several parties with limited prospects. Some of these parties have punched well above their weight in terms of their political importance and/or influence on the political forefront. Although some third parties never even achieve federal Official Opposition status, a few have exercised power and influence in minority governments. Some have held office provincially, and thus won a high profile there, even if nowhere else. All are expressions of Canadian political culture and values; none are unworthy of study.

Since the early 19th century, political organizations that offer a critique of the constitution, the establishment, or government practices have seized the “reform” banner. Some made use of the name while others described their mission as one that had a reforming agenda. This distinguishes them from the mainstream parties (since 1867, the Liberals and the Conservatives) in that they sought more than a crack at power. Beginning in the late 19th century, social reform and financial reform movements generated political expressions. Perhaps because they had the sensibilities of a movement, some of these political parties were able to survive years of disappointment.

First and Second Parties

In order for the Grits and the Tories to become the Liberals and the Conservatives, respectively, they had to create the political machinery necessary to succeed at the polls across the country. This was no small task. In 1867, the Grits were heavily concentrated in southern Ontario and the Tories were part of an urban and landed elite in both Ontario and Quebec: neither showed much natural ability at expanding their reach. Within 30 years, however, the Liberals and the Conservatives held a duopoly on the federal and provincial stages alike. There were a few exceptions. In British Columbia, for example, party lines were not introduced until 1903. Otherwise, the 19th century closed with a political ecology in Canada that was all but identical to that of Britain, consisting almost exclusively of Liberals and Conservatives.

What happened in the 20th century was, in some respects, a return to the politically fractious pre-Confederation days of Grits, Rouges, Tories, Patriotes, Reformers, and Bleus. And while Canada did not follow Britain’s (and Australia’s) lead in forming a Labour Party, neither did it conform to the rather limited vision of political options available to Britons, Antipodeans, and Americans. Canada experimented. Having said that, the multi-party system that emerged by the 1920s did not produce a rash of minority governments comparable to what happened in 20th century France and Italy. At the provincial level, the Maritimes would remain loyal to the binary options of Liberals and Conservatives in federal and provincial politics; the same could not be said of the rest of Canada, not even Ontario.

Factionalists

Within the established parties there have always been small break-away movements. Most instances see a disaffected elected representative or two leave their party caucus and sit as “Independents.” Sometimes Independent candidates will successfully seek election, although to do so they have to overcome the party machinery on which their opponents might call. More commonly in the 19th century, a hyphenated allegiance would be used in order to make the best of two partisan brands. Macdonald tried this himself when he promoted his party as the “Liberal-Conservatives” in the earliest days of Confederation. By 1873, the label had been dehyphenated and the “Liberal” part appropriated by the Grit-Rouge alliance. At about the same time, a “Conservative-Labour” candidate was elected to Parliament from Hamilton — the first working-class MP. Seeking to distance themselves from imperialists within their party, from 1878-1911, several Quebec Conservatives ran as “Nationalist-Conservatives.” By way of contrast, the hard-line, anti-Catholic, anti-French politician Dalton McCarthy (1836-98) eschewed any part of the established parties’ brand when he broke with the Conservatives and established his own slate of candidates in the 1896 election. They were known (modestly) as “McCarthyites.” Only McCarthy himself was ever elected and he died two years later in a traffic accident.

The 20th century saw still more schisms in the main parties, but most remarkable was the ability of the Conservatives and Liberals to reel in their factional elements.

The United Farmers

It is perhaps ironic that farmers’ parties arrived on the scene when they did. After all, the 1921 census showed that Canada had crossed a threshold and was now more urban than rural.

The first third party movement to win a majority of seats in any jurisdiction was the United Farmers of Ontario (UFO) in 1919. Despite its urban centres, Ontario south of the Canadian Shield was still heavily rural. Every constituency had enough farmers’ (and farmers’ allies’) votes to leave the old parties behind. Although the UFO administration was brief — it lasted only one term, from 1919 to 1923 — it was a breakthrough in that it showed the possibility of sectoral appeals across a whole province. The 1919 campaign involved a tactical alliance with the moderate Independent Labour Party of Ontario: the ILP didn’t run candidates in rural areas and the UFO stayed out of urban constituencies. The result was a coalition partnership that accomplished quite a lot in terms of early welfare legislation, prohibition, and the establishment of co-operatives, but failed to deliver one of its more innovative reforms: proportional representation.

The UFO election was followed quickly by similar triumphs in the West. The United Farmers of Alberta (UFA) were elected to govern in 1921 and the United Farmers of Manitoba (UFM) won a significant number of seats in 1920. Ottawa’s wartime refusal to lift tariffs was an important source of UF popularity. Indeed, a common thread in the rise of the United Farmers was their anti-Ottawa posture. Criticism of the tariff component of the National Policy had failed to shift the Conservatives. The Liberals, for their part, blew hot and cold on free trade with the United States, despite farmers’ demands for reciprocity. What’s more, a succession of Liberal and Conservative provincial governments had failed to win concessions from federal governments. Local voters felt there was nothing to lose in voting United Farmer.

The Progressives

In 1919, the federal Union Government’s Minister of Agriculture, Thomas Crerar (1876-1975), split with the Borden administration over its apparent disregard for farmers’ issues. The United Farmers ran candidates successfully in a handful of federal by-elections in 1919 and 1920, which led Crerar to form a national pro-agriculturalist party. The result was the Progressive Party, which ran its first campaign in 1921, stealing 58 seats nationally and forming the second largest caucus in Ottawa. By rights, this should have made Crerar the head of the Official Opposition. The Progressives, however, were heavily influenced by populist and agrarian movements, particularly in the United States. They didn’t like caucus accountability and discipline and they preferred to vote their (individual) conscience. The Progressives turned down the opportunity to enter into a coalition with the Liberals under King and they passed the title of Official Opposition off to the third-place Conservatives under Arthur Meighen (see Section 6.7). While these decisions and tactics arose from the anti-party philosophy of the Progressives, they doomed the organization to insignificance in the House of Commons. It has been suggested by some analysts that the Progressives’ atomistic approach means that they weren’t a party at all, just an expression of the United Farmers movement. This may be true, but it is all too easy to understate their appeal in the Canadian heartland: half of their MPs came from Ontario, where the Progressives won a quarter of the province’s federal seats. (They were unable to make much headway in the Maritimes.)

By 1926, the independently minded Progressives had unraveled. Crerar resigned and the House Leader was now Robert Forke (1860-1934), a veteran of the Liberal Party from Manitoba. When the Conservatives briefly formed a government in 1926, Forke took the Manitoban Progressives into the Liberal Party where they were quickly subsumed into the older organization. Ontarian support dissolved and the more hard-line Albertan members washed their hands of the Progressive label and sat as “UFA” representatives in Parliament. Although “Progressives” were still winning seats in the 1930 election, their numbers were down to single digits. Some of the Albertans were part of a more radical labour-farmer alliance with a strong social gospel pedigree. This group would go on to found the core parliamentary element of the CCF (see below).

What remained of the Progressive Party disintegrated during the 1930s and Crerar was welcomed formally into the Liberal fold. He was rewarded with a cabinet post and a seat in the Senate. The “Progressive” name, however, was appropriated by the Conservative Party, thus the “Progressive Conservatives” from 1942 to 2003.

The Reconstruction Party

H.H. Stevens, a high ranking cabinet minister in the Tory governments of Meighen and Bennett, bailed on the latter on the eve of the 1935 election and formed the Reconstruction Party. Isolationist and inclined towards appeasement of the fascist powers in Europe, the Reconstruction Party finished third in the election with nearly 10% of the popular vote but won only one seat: Stevens’ own in the Kootenays. The party folded and Stevens rejoined the Conservatives, despite the fact that Reconstruction’s campaign split the vote in dozens of constituencies and ended up costing the Tories dearly.

The Left

Among the first political movements to achieve some measure of success were the Socialists. The Canadian Left took many forms, however, and there were more splinters and fragments on this side of the ideological spectrum than on the Right.

The Socialist Party

The Socialist Party of British Columbia (SPBC) was the first of several like-minded organizations to elect a candidate to a provincial legislature. They elected two in 1903: Parker Williams and James Hawthornthwaite. Late in 1904, the SPBC fused with socialist parties from across the Prairies and Ontario to create the Socialist Party of Canada (SPC). The whole array was, from the 1890s through the 1920s, deeply divided over the issue of reform versus revolution. An important and influential faction — dubbed impossibilists — argued against any gradualist or reformist approach to capitalism, maintaining that ameliorating the worst effects of the existing system would only enable it to last longer. This made the business of holding elected office exceedingly difficult for representatives of the SPBC and SPC: if they were able to secure better conditions for workers, they would lose the support of the impossibilist faction — if they didn’t, they would likely lose the support of the electorate. Even as the SPC’s membership and support level was growing during the first decade of the century — by 1910 it was the third largest party in Canada — moderate elements were leaving to form more reform-oriented social democratic parties.

The SPC continued to enjoy success in British Columbia until the Great War. In the 1912 provincial election, the SPC won 11% of the vote, a high water mark for third parties in the furthest West before the end of the war. Nationally, however, the party entered into a difficult phase. Its anti-war stance, which grew out of an internationalist view of the working-class, brought it under the lens of national security monitors. Its members were harassed, its mail was tampered with and seized, and its newspaper (The Western Clarion) closed down. The revolution in Russia in 1917 led to the formation of a Canadian communist movement that was increasingly critical of the SPC. Attacked from the right and the left, the SPC staggered into the 1920s and collapsed in 1925, most of its members having left to join the communists.

Communist Parties

The Russian Revolution of 1917 inspired some Leftists to pursue a new organizational approach. The War Measures Act was still in effect in 1921 when the founding meetings took place and the ban on any “communist party” obliged the use of a different banner: the Workers’ Party of Canada. The ban was lifted in 1926 and the Communist Party of Canada (CPC) appeared. The Party struggled with the principal issue that divided communist parties internationally: whether to pursue a worldwide revolution or to support the goal of a successful revolution in Russia. Factions supporting international revolution (Trotskyites) were expelled from the party by the dominant Stalinist elements representing the will of the Communist International (aka the Third International, the Comintern).

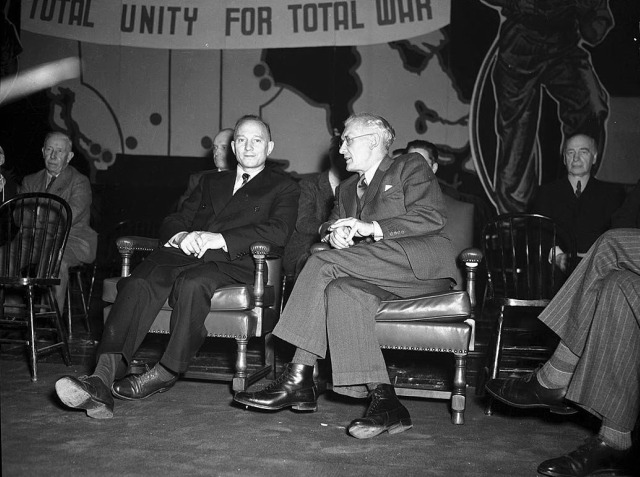

When the 1930s began and the western world entered into a deep and (as it turned out) protracted crisis in capitalism, support for the CPC and similar movements grew. This resulted in an escalation of state surveillance and harassment. The 1931 arrest and imprisonment of Tim Buck (1891-1973), the leader of the CPC from 1929 to 1962, drove much of the CPC machinery underground. When Buck was released in 1934, he was met by a 17,000-person rally at Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens, a further sign that support for the CPC was growing while the economy was sinking. CPC efforts to organize the single transient unemployed were particularly effective and resulted in the establishment of the Relief Camp Workers’ Union and the Workers’ Unity League. The CPC was also able to forge anti-fascist partnerships with more moderate left-wing movements and it played a leading role in founding the 1500-member Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion that was sent to Spain to fight the fascists in the Civil War in 1837-38. Not that this initiative improved their relationship with an increasingly anti-fascist government in Ottawa: when war against Germany and Italy erupted in 1939, the “Mac-Pap” veterans were categorized by the federal government as “premature antifascists” and potential subversives.

At the provincial level the Communists were hounded particularly hard by the government of Quebec. The so-called “Padlock Law” of 1937 (officially, in English, an Act to Protect the Province Against Communistic Propaganda) was used to close down communist presses and to imprison anyone involved in production or distribution of printed materials for up to three years. It would be another 20 years before the law was struck down as unconstitutional.

The Party itself walked a difficult tightrope on international issues. Anti-fascist in 1938, they adhered to the Comintern’s anti-war strictures until 1941. The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 — a mutual non-aggression agreement between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia — was meant to produce a war between capitalist nations. In that context the CPC was viewed by Ottawa as an organization intent on subverting the war effort of the western Allies, not least of which because the Soviet Union was busily annexing the Baltic nations and badgering Finland. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941 and the USSR joined in the battle against the Axis Powers, the status of the CPC and its members improved dramatically.

The party reached a zenith of popularity in 1945, when Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union was Canada’s indispensable ally. In the general election of that year, the CPC’s Labor-Progressive Party (LPP) pulled in over 2% of the national vote and won one seat. The LPP ran candidates until 1959 and the CPC after that. It failed to win a single seat after 1945.

Support for the Communists was progressively gutted from the mid-1950s onward. Soviet President Nikita Khruschev’s damning 1956 speech on Stalin-era purges and atrocities caused some members to leave the party, as did the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian Revolution that same year. Disclosures of anti-Semitism at the highest levels of the Soviet Union further alienated members of the CPC, many of whom were Jewish. The Soviet assault on Czechoslovakia’s 1968 rising was cause for further desertions in the decade that followed.

There was a surge in electoral support for the CPC in 1974 when it secured 12,100 votes in the federal election. But by any standard, this was an abject failure as a partisan endeavour. Things worsened for the party at the polls as the Cold War ground to a close. The collapse of the Soviet Union flushed out divisions within the CPC and its assets became, in 1991, the subject of an acrimonious and very public separation battle. The party re-established itself thereafter as an organization dedicated to Marxist-Leninist ideals and it continues to operate in provincial, civic, and federal elections.

Social Democrats

The branch of the political tree that produced the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) and the New Democratic Party (NDP) had roots in the social reform movements of the 19th and early 20th century: the United Farmers movements, the Progressives (discussed below), labour organizations like the Knights of Labor, trade unionism, the cooperative movement, and a wide range of socialist philosophies. Established as a national political party in 1932, the CCF ran in its first election in 1933 in British Columbia, where it became the Official Opposition. Thereafter, the party enjoyed success principally at the provincial level, particularly in three of the four western provinces, but it also played a key role in federal politics both in its original form and, later, as the NDP.

The core elements of the moderate socialist movement came together in 1924 in Ottawa. The Progressive Party was nursing closer relations with the Liberal Party and were, some of its members believed, abandoning several key values. Five United Farmers MPs from Alberta and one from Ontario formed a faction within the Progressive Party — a party within a party — and they were joined soon after by five other Progressives, along with four Labour MPs, and four Independent Labour Party MPs. Together this was the Ginger Group, a coalition of like-minded men and one woman. What they brought together was a shared belief in the need for greater equality of opportunity and living standards across the social classes, elimination of the worst effects of competitive capitalism, and political reform that included an extension of greater rights to women. In the midst of an economic boom, their voices were largely drowned out. Eight years later, in the midst of the Great Depression, what they had to say appealed to a far greater number of Canadians.

This wasn’t the first attempt to forge a common front on the left of the Canadian political spectrum but it had certain qualities that gave it the possibility of greater longevity. For starters, it was a group made up mostly of men who were in their mid- to late-forties; that is, they were all (but one) born in the late 1870s or early/mid-1880s and were thus mostly too old to have served in the Great War. They constituted a peer group that was neither too young to be dismissed as immature radical cranks, nor so old that they seemed out of touch with any particular demographic. Farming backgrounds were a common denominator, as was Methodism, Presbyterianism, and a commitment to the goals of the cooperative movement. They had some occupational range: their number included a lawyer and an upholsterer. The two outliers in the group were to have, arguably, the greatest impact on the Ginger – CCF project. J.S. Woodsworth (1874-1942) was the oldest and came into the Group with a reputation as a writer, a Methodist minister and teacher, a pacifist, a labour activist, and a leading light in the social gospel movement. He was also an architect of Canada’s first old age pension legislation in 1926 and so demonstrated how the state could play a direct role in alleviating hardship. This was a significant reversal from the old “Poor Law” mentality of the 19th century and opened the door to social welfare legislation across Canada. Woodsworth would become the de facto leader of the Ginger Group and officially, in 1932, of the CCF. The other peerless member of the Group was Agnes Macphail (1890-1954), the youngest of the founders by three years, the only woman, and the only representative of the United Farmers of Ontario. Macphail was a “firster,” first woman elected to Parliament, one of the first women elected to the Ontario legislature, the first woman to represent Canada at the League of Nations (the precursor to the United Nations), and the first president of the Ontario CCF. A Methodist in her youth, she was swept up in the evangelical movement in the early 20th century. Macphail worked as a school teacher before pursuing a career in politics, and the very act of being a female “career politician” constituted another first. She wasn’t directly involved in the Persons Case of 1929 but was almost a beneficiary; she was about to be offered a seat in the Senate when she died in 1954. Macphail’s significant contribution was both symbolic and practical. She demonstrated by her presence that the social democratic movement was a welcoming place for women in politics and, as a pioneer woman in Canadian politics, she set the bar high for accomplishments.

By the 1930s the Ginger Group itself had fractured; some of its members had retired from politics or had been voted out of office. The economic crisis, however, pulled others into the conversation about a political mechanism for achieving social change. These included the League for Social Reconstruction (LSR), a socialist think-tank (before the words “think” and “tank” were ever combined) led by two outstanding Canadian intellectuals. Frank Underhill, a historian at the University of Toronto, and F.R. Scott, a Law professor at McGill University, very informally founded the LSR with an eye to building a national network of intellectuals who could shift the conversation about the causes of and solutions to the Depression along a constructive, socialist path. Both Underhill and Scott were convinced that capitalism was at the root of the Depression, not moral or social issues; that only systemic changes that delivered socialist policies could change things for the better. The LSR lasted barely a decade and was responsible for building support for the idea of social, economic, and political planning across the party spectrum. It was joined early on by two figures who would play important roles in Canadian politics: Eugene Forsey (1904-91), a young political economist from Newfoundland via Oxford University and elite circles in Toronto, and David Lewis (1909-81), a brilliant Rhodes Scholar and political animal, freshly returned from England. Lewis, like A. A. Heaps (1885-1954) — one of the original Gingers — was a Jew and a consistent and strident opponent of the Communist movement.

In 1932, Underhill and Scott met with the Ginger Group in Ottawa and began the process of founding what they initially called the “Commonwealth Party.” A convention was held in 1932 and, influenced by the agrarian socialism of the UFA, “Cooperative” was added to the party’s name, and its many threads recognized in the word “Federation.” For a while the party banner also carried the words “Farmer-Labour-Socialist”. In 1933, at the second convention, the main tenets of the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation were codified into the Regina Manifesto; these included an ambitious program of social welfare legislation, national ownership of key industries, and a program of universal healthcare. The Manifesto also called for an end to capitalism, a resolution that would be a red rag to anti-communists for the next two decades.

Almost immediately the CCF scored important victories that dwarfed the achievements of any other socialist party in Canadian history. Official Opposition status came first in BC, then in Ontario, but it was in Saskatchewan where the party first formed a government, in 1944. The first socialist government in North America, it would serve as an example of social democratic programming for the rest of the country, piloting the universal healthcare program that was embraced by Ottawa in the 1960s.

Outside of Saskatchewan and British Columbia (where it continued as the Opposition), the post-War years were grim for the CCF. The CCF found itself undermined by the Communists and targeted by an increasingly paranoid Cold War media. To be sure, there were CCFers who came to the party via more ideologically Marxist organizations and some espoused a radical position regarding property and capitalism. David Lewis spent years trying to minimize their impact on the party’s policies and profile. In 1956 he finally succeeded, replacing the Regina Manifesto with the much milder Winnipeg Declaration. He was aided in this campaign by another CCF veteran of the 1930s, M. J. Coldwell (1888-1974), who undertook a purge of the party’s red elements and repositioned the CCF as an opponent of the Soviet Union. By the late 1950s, however, campaigns against the Left had reached such a pitch that the CCF was all but irrelevant in most jurisdictions.

At that point, the newly restructured national labour centre — the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) — negotiated a partnership with the CCF. This produced, in the course of nearly seven years, the “New Party,” a CCF-CLC collaboration that changed its name in 1963 to the New Democratic Party (NDP). Tommy Douglas, the former CCF premier of Saskatchewan, took over the leadership and the social democratic party’s fortunes began to improve instantly. There was steady growth through the 1960s and in 1972, the NDP secured enough seats to hold the balance of power in Pierre Trudeau’s minority government. This was an opportunity to push through social democratic legislation in exchange for propping up the Liberals. The next election, in 1974, cost the NDP dearly; its share of the popular vote hardly changed but it lost half its seats in Parliament nevertheless and was reduced to the third party once more.

There were, however, some victories at the provincial level. The first Manitoban NDP government was elected in 1969 under Edward “Ed” Schreyer (b.1935); Allan Blakeney (1925-2011) revived the Saskatchewan NDP in 1971, forming a government that would last until 1982; in BC in 1972, David Barrett ended 20 years of Social Credit government under W.A.C. Bennett but his NDP government would endure a mere three years; the Yukon NDP formed its first government in 1985 under Tony Penikett (b.1945) and held on to power until 1992. In Ontario, the provincial NDP would go from a position of strength in the 1970s to even greater strength in the 1980s. Beginning with David Lewis’ son Stephen (b.1937), then Bob Rae (b.1948), the NDP headed up the Official Opposition in the legislature (Lewis, 1975-77) and held the balance of power (Rae, 1985-87), until forming the government (Rae, 1990-95).

NDP claims of being a national party remained more wishful thinking than empirically verifiable through the late 20th century. The party continued to be marginal in Alberta, Quebec, and the Maritimes. In the rest of the country, however, and especially under the leadership of Edward “Ed” Broadbent (b.1936) from 1975 to 1989, the NDP’s central role in federal politics became increasingly confirmed. By the end of the 1980s, it was clear that Liberal and NDP candidates were fighting over Left-centrist votes, a fact that split their possible combined support and thus contributed to two Conservative governments under Brian Mulroney. The last decade of the century would see the NDP’s fortunes slide. Audrey McLaughlin (b.1936), the first woman (and first Yukoner) to lead a national party, took the NDP through the economic turmoil of the early 1990s and some of their weakest results nationally (and worst years provincially) before handing the mantle on to Alexa McDonough (b.1944). McDonough, a Nova Scotian, kept the party afloat to the end of the century when, in 2000, it narrowly avoided losing official party status.

The CCF-NDP drew on several progressive threads in Canadian society and culture, some of which became severely entangled. The agrarian radicalism of the Progressives and United Farmers, the militant unionism and revolutionism of the Socialist Party of BC, the Fabian democratic socialism of the LSR, and the powerful and persistent influence of the Social Gospel gave it both a broad foundation to build on and the raw materials for continuous infighting. With the addition of the CLC it became a kind of Labour Party, but it did so in a way that would guarantee tensions between the CLC elements and those more associated with CCF values. When, in 1969-71, a faction within the NDP emerged that embraced left-wing nationalism, feminism, social activism and called for an independent socialist Canada, many of the fracture lines within the Party were laid bare. The Waffle, as the splinter group was known, failed to take over the leadership of the national party but the question remained as to whether the NDP was the party of organized labour or the party of social justice and socialism. These debates continue within the party and are unlikely to end anytime soon.

Social Credit and the Ralliement Créditistes

In 1924, a British engineer and former soldier, Major C.H. Douglas (1879-1952), published a densely argued treatise on a flaw within capitalism. The costs of goods produced across a spectrum of industries, he pointed out, were invariably greater than the wages paid out to the people producing them. This meant that there was not enough money in circulation to purchase what was being manufactured. Consumers, he argued, were invariably at a disadvantage and the whole of the economy continually headed toward bottlenecks. To solve this conundrum, he proposed a system of credits that would be applied across society and a radically changed democratic system that, together, would empower the populace as consumers and political actors.

Douglas was one of a great many economic theorists in the Interwar years — offering up ways to overhaul or replace conventional capitalism and address the shortcomings of liberal democracy. His ideas and analyses were complex and roundly criticized by economists. His suggestions, however, found purchase in two places in particular: New Zealand and Canada.

The concept of social credit landed in Alberta in the late 1920s and might have disappeared if not for the conjunction of several elements. Politics in Alberta had taken on a strong evangelical tone thanks, in part, to the social gospel themes and rhetoric employed by the ruling United Farmers party. The idea of preachers in politics was widely accepted and a certain amount of trust and even deference was enjoyed by evangelical clergymen. Not surprisingly, the high-energy, “tub-thumping,” “fire-and-brimstone” preachers were among the most compelling.

The most widely recognized voice of religion in the early 1930s in Alberta was that of “Bible Bill” Aberhart (1878-1943). A school principal and Baptist minister, Aberhart established the Calgary Prophetic Bible Institute and took to the airwaves with a weekly radio evangelical program. He was a pioneer in this respect, what today we would call an “early adopter” of communications technologies. Moreover, Aberhart’s own deep rolling voice was joined behind the microphone by a team of actors who played out moral parables on live radio. His audience was huge, and radio at this time — played in the home on a wireless set that was often the beautifully designed centerpiece of the parlour or front room — was listened to in a manner that involved a kind of quiet engagement by everyone in the household. Aberhart would invite his listeners to consider what they heard and to discuss it, as though they were holding a seminar or a bible-reading group in their own home. Why does this matter? A member of the Prophetic Bible Institute introduced Aberhart to social credit theory and the latter quickly saw it as a solution to the crisis of the Depression. He became so convinced of its potential that he promoted his understanding of Douglas’ theories from the pulpit and, more importantly, through his radio program. (One particularly effective episode involved a recurring character, the “Man from Mars,” who commented on the inexplicably strange things Earthlings do, offering Martian solutions to crime, immorality, and unemployment and the use of social credits.)[1]

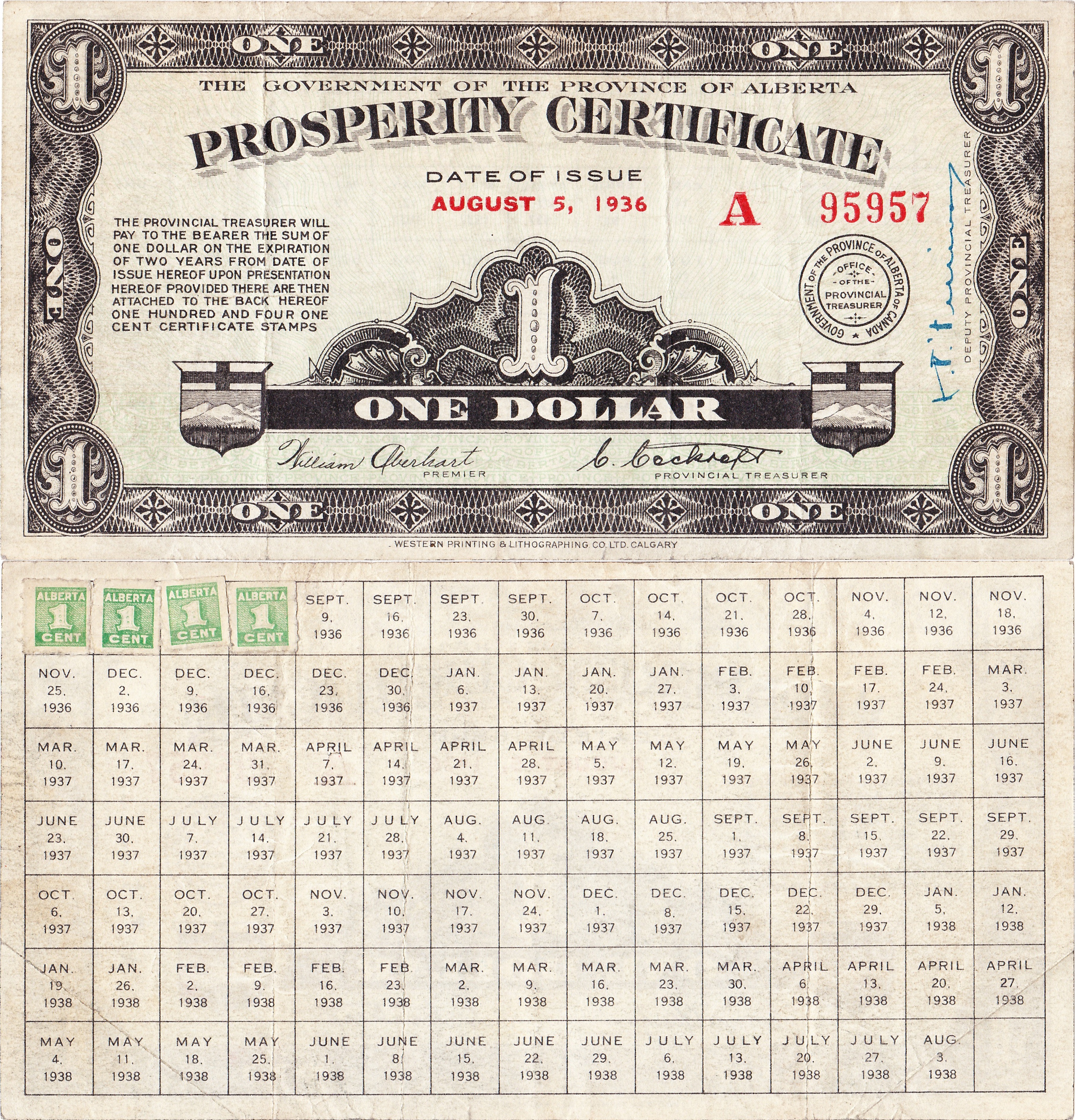

The failure of the United Farmers to take up the social credit idea launched Aberhart into politics. In 1935, the Social Credit Party — helped by scandal in the UFA — won a landslide victory. Success at the polls was not matched by fiscal victories: issuing social credits meant, in essence, producing a currency, something that was exclusively reserved to the federal government. The coupons or “scrip” were fiscally, operationally, and constitutionally problematic, so much so that the lieutenant-governor of Alberta refused to pass into law Aberhart’s experiment, which became derided as “funny money.” This didn’t stop Social Credit from holding onto power in Alberta for the next 36 years, nor did it stop its spread across Canada.[2]

Outside of Alberta, the ideas behind social credit produced three different partisan typologies. Douglas’ beliefs regarding democracy were complex and in some ways idiosyncratic while simultaneously typical of the imaginative hothouse that was the 1920s. He advocated government by experts (he was, after all, an engineer) and believed politicians should act as middlemen between the voters and the planners. Aberhart echoed this perspective, especially if he was cornered on a difficult aspect of economic theory. In a statement that acquired some fame, he said:

You don’t have to know all about Social Credit before you vote for it. You don’t have to understand electricity to make use of it, for you know that experts have put the system in and all you have to do about Social Credit is to cast your ballot for it, and we’ll get experts to put the system in.[3]

But Aberhart was a partisan and Douglas didn’t like parties. This thread of his thought took shape in Quebec in the 1940s with the Union des électeurs and briefly in Ontario by the similarly named Union of Electors.

The second typology was the more conventional party format, like that in Alberta and the Social Credit Party of Canada (SCPC). The national party struggled from 1953 to 1958 when they were wiped out by the Diefenbaker landslide in the West. But the party had a base of support in Quebec as well and it rebounded in 1962, winning 29 seats, all but four of them in Quebec. This gave Social Credit the balance of power in Parliament, which they used a year later to oust the Diefenbaker minority. Shortly thereafter, the national party split and the larger part of the caucus formed the Ralliement des créditistes under the leadership of Réal Caouette (1917-76), the remainder keeping the SCPC brand. As a “third” party they typically finished fourth in Parliamentary seats, behind the NDP. In 1972, Caouette’s Ralliement won 15 seats but began an unbroken slide into the 1980s, after which it was frozen out. Never at risk of forming a national government (nor a provincial one in Ontario or Quebec), the eastern and national parties continued to support the economic theories of Douglas, and to espouse anti-Semitic and occasionally pro-fascist sentiments. Caouette was, too, a Quebec nationalist but also a rabid enemy of radical separatists like the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ).

The third type of Social Credit Party was that of W.A.C. Bennett (1900-79), the charismatic premier of British Columbia from 1952 to 1972. Bennett, a former Conservative Member of the Legislative Assembly, split with his old party and was able to take the reins of a slow-moving Social Credit Party that was largely populated by former Albertans. Once he formed government he never spoke again of “funny money” and the party, for all intents and purposes, pursued the (right-of-centre) politics of populism and pragmatism. After he won a majority in 1953, Bennett disposed of BC’s peculiar preferential-ballot system and restored the conventional first-past-the-post model. Informed by small-town piety, devotion to private (especially small) enterprise, and a Cold War-era loathing for unions and the Left, the party took a breather during the Barrett/NDP administration of 1972-75 and then governed for another 16 years before falling apart in the 1991 general election.

The conservative Christian values of Social Credit’s various incarnations has meant that its support has mostly migrated to parties on the Right. Preston Manning’s Reform Party attracted some based in part on the leader’s long connection with Social Credit (Manning’s father succeeded Aberhart as Premier from 1943-68) as did the electorally insignificant Christian Heritage Party. The pragmatism of the leadership — exemplified by W.A.C. Bennett and his son and successor, William “Bill” Bennett, also enabled its constituency to find a home in the BC Liberal Party. The Ralliement articulated a conservative nationalism consistent with Duplessis’ Union Nationale along with some aspects of both the Parti Québecois and the Bloc Québecois (see Section 9.9 and Section 9.10).

Key Points

- The Canadian parliamentary system enables the establishment of alternative political parties.

- Historically, some reform movements have taken the form of political parties. These have included agrarian parties like the United Farmers and the Progressive Party, socialist parties like the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation/New Democratic Party and the Communist Party of Canada, and the various parties associated with social credit.

Media Attributions

- Tim Buck at Maple Leaf Gardens © City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1257, Series 1057, Item 7099 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Annie Buller addressing a crowd before the Estevan Riot © RCMP is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 1936 Alberta Prosperity Certificate is licensed under a Public Domain license

- David R. Elliott and Iris Miller, Bible Bill: A Biography of William Aberhart (Edmonton: Reidmore Books, 1987), 151. ↵

- Two studies addressing the theoretical elements of Douglas' social credit and the practicality of some of his aims in Alberta are Alvin Finkel, The Social Credit Phenomenon in Alberta (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1989) and Bob Hesketh, Major Douglas and Alberta Social Credit (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997). ↵

- Aberhart to John Hargrave, and Albertans, during a 1935 election campaign. Originally from the Edmonton Journal, (14 August 1935), and cited in Harry Hiller, Religion, Populism, and Social Credit in Alberta [PDF], p. 375, (PhD Thesis, November 1972), accessed 13 May 2016, https://macsphere.mcmaster.ca/bitstream/11375/13785/1/fulltext.pdf. ↵

Electoral system in which the candidate receiving the greatest number (though not necessarily a majority) of ballots wins; considered problematic by some when a party wins a majority of seats while winning much less than a majority of votes.

In parliamentary systems, the party with the second largest number of seats in the House of Commons. On occasion, the second largest caucus has refused the title of Official Opposition.

Distinct from the first-past-the-post system; can take several forms but common aspect is that political parties will be elect a number of seats that reflect in some measure the percentage of votes the parties receive. For example, in a first-past-the-post system a party might win 49% of the votes in every constituency but not elect a single candidate if the only other party running wins 51% of the votes; proportional representation (sometimes called PR) would ensure that the second-place party received something closer to 49% of the seats.

The position that political parties constitute an unwelcome constraint on democratic politics.

Coined during the French Revolution to describe opponents of the monarchy; since then, used to describe a spectrum of reform and radical positions and political organizations that includes some Liberals, the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, the New Democratic Party, the Socialist Party of Canada, and — at the far end of the Left — the Communist Party and, in some instances, anarchists. See also Right.

Individuals, groups, and parties espousing a conservative perspective; a broad continuum that includes Red Tories, Blue Tories, neo-liberals/conservatives, the late 20th century Reform Party, and — far to the Right — fascists.

Among left-wing activists, a belief that it is impossible to reform capitalism and that it must be overthrown rather than overhauled. See also gradualist and reformist.

The idea that great change can occur incrementally, in slow, small, and subtle steps, rather than by large uprisings or revolutions. Among left-wing activists, a belief that reforms to capitalism can produce a social and economic order of fairness for working people; sometimes called “Fabianism;” derided by revolutionaries as delusional. In the context of Quebec’s independence movements the equivalent term is étapisme. See also reformist and impossibilist.

Among left-wing activists, a belief that incremental changes to capitalism can produce a social and economic order of fairness for working people; derided by revolutionaries as delusional. See also gradualist and impossibilist.

A political movement that advocates reform that will achieve greater social equality, a degree of socialist governance, and the preservation of democratic institutions. Associated with the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation and New Democratic Party.

In the history of organized labour, the belief that workers of all countries had more in common than they did with co-nationals who belong to other social classes. Views nationalist movements as antithetical to the interests of working people.

Also the Communist International, the Third International; 1919-1943; called for world revolution and the establishment of communist regimes.

A 1,500-strong contingent of Canadian volunteers in the war against the Fascists in Spain during the Civil War, 1937-38; took their name from the two leaders of the Rebellions of 1837-38, Louis-Joseph Papineau and William Lyon Mackenzie (the grandfather of Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King).

A mutual non-aggression treaty signed between Germany and the USSR; allowed Germany to move forward with its attacks on France and the Low Countries while the Soviet Union annexed territories in the Baltic region.

Building on the scientific socialism of Karl Marx, which argued that socialist, worker-led governments would supersede bourgeois capitalism, the Leninist thread — arising in revolutionary and post-revolutionary Russia — introduced the idea of a vanguard of the proletariat, single-party rule, internationalism, and a state-run economy. In Canadian communism, one of several variants on Marxist doctrine.

An alliance of progressive MPs in Ottawa that led to the founding of the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF).

Also spelled co-operative. Established in growing numbers in Britain in the mid-19th century and is associated with the “Rochdale Pioneers”; several typologies; goals include making available goods and/or supplies to members at low costs by taking advantage of economies of scale as a group, also obtaining optimal prices for community products by pooling output for sale. Surpluses and profits are redistributed to members of the cooperative; some have an educational mandate as well. Examples include grocery stores, housing co-ops, and the dairy industry. See also wheat pools.

A socialist think-tank established by Frank Underhill and F.R. Scott in 1932.

1933; the original statement of purpose and beliefs of the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation.

Fully, the 1956 Winnipeg Declaration of Principles of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation; replaced the Regina Manifesto; significant in that it moved the party away from socialism and closer to democratic socialism and a pro-union position; made possible the alignment of the CCF with the CLC very soon after.

Successor to the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation; created out of the union of the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) and the CCF in 1961.

In international relations, refers to a complex of evenly weighted alliances that theoretically prohibit any one participant or side from going to war.

The recognition of a political party’s representatives in an assembly as sufficient to merit certain parliamentary privileges, including the right to ask questions during question period. In Ottawa, the federal House of Commons requires that a party have no fewer than 12 MPs in order to qualify for official status.

A belief that reforms to capitalism can produce a social and economic order of fairness for working people; sometimes called “gradualism.”

A faction within the NDP in 1969-1971 that embraced left-wing nationalism, feminism, and social activism, and called for an independent socialist Canada.

Primarily an economic theory and monetary policy, developed in the 1920s and touted as a solution to the Depression in Canada by Social Credit political parties.