Chapter 5. Immigration and the Immigrant Experience

5.10 Female Immigrants and the Canadian State, 1860s through the 20th century

Lisa Chilton, Department of History, University of Prince Edward Island

In the middle of the 19th century, women who immigrated to Canada became the focus of special attention. Philanthropists and social reformers began to lobby officials of the Canadian state to help support their efforts to manage and protect this special class of newcomers. In part, the impetus behind treating female immigrants differently to men was a growing sense that the Canadian nation would be defined by the quality of the people who were settling it. As mothers – symbolically and literally – of future generations of Canadians, female immigrants were considered by architects of the new nation to be particularly significant additions to the population.

The Canadian government (like its counterparts in the United States, Britain, Australia, and other parts of the British Empire) initially resisted pressure to invest in special programmes and facilities for female migrants. The earliest initiatives were all privately funded. But by the turn of the 20th century various government bodies were supporting programmes designed by organisations such as the British Women’s Emigration Association, the Young Women’s Christian Association, and the Travellers’ Aid Society to treat women as both a particularly vulnerable and a potentially problematic class of immigrants. For example, the earliest women-only hostels and transatlantic chaperone programmes were all fully funded by charitable and philanthropic organisations. By the beginning of World War I women-only immigrant reception homes, established and run by women associated with the British Women’s Emigration Association but financially underwritten by Canada’s federal government, were in place in major urban centres across Canada.[1]

The Canadian government’s consideration of female immigrants as a group requiring particular care came to a head after World War I. In 1920, after much lobbying by Canadian women’s associations, the Canadian federal government established a special branch of the Canadian Department of Immigration and Colonization to recruit women for domestic service and other female-gendered forms of paid employment that Canadian women were unlikely or unavailable to perform, and to manage the movements of all “unaccompanied” women coming into the country. The Women’s Division functioned as a separate unit for just over a decade before the government imposed restrictions to immigration during the Great Depression and the flow of immigrants dried up, making their work essentially unnecessary.[2]

While the Women’s Division disappeared, the gendered assumptions and attitudes behind its establishment continued to play major roles in state programmes associated with newcomers after World War II. Women’s sexual histories were interrogated as a part of the selection process to a far greater extent than were those of men. Local government bodies funded immigrant reception programmes that encouraged female immigrants to embrace mainstream Canadian parenting and homemaking practices. And, as had been the case since at least the beginning of the 20th century, the government barred entry to women and even deported female immigrants for past experiences and behaviours that might have been overlooked in their male counterparts. Thus, for example, in the early 20th century, unmarried women who became pregnant were vulnerable to deportation proceedings on the grounds of their immorality and the likelihood that they would require some sort of charitable assistance if they were allowed to stay in Canada.[3]

The most consistent area of investment relating to female immigrants by the Canadian government concerns recruitment. Because household work and care for the young, the ill, and the elderly typically have been low-paid, exploitative areas of female-gendered employment, Canadian citizens in a position to be more selective have shunned this work. At the same time, prospective employers were quick to assign stereotypes to immigrant women seeking work in these fields: The newly arrived female worker was caricatured as morally suspect because of her race or ethnicity. Public fears and xenophobia in this respect produced extensive scrutiny and regular criticism of government programmes, even as the number of recruitment exercises grew. Perhaps more than any other aspect of the Canadian government’s immigration work, the government’s recruitment programmes associated with domestic and caregiver work represent Canada’s most conservative social politics.

Through domestic servant, caregiver and nurse recruitment schemes, many thousands of women have immigrated to Canada since Confederation. Before World War I, the majority of domestic servants in major urban centres and in the Canadian West were immigrants from the British Isles. They had been recruited by philanthropic organizations heavily subsidized by the Canadian federal government. Throughout the 1920s, the Canadian government continued to invest heavily in the recruitment of British women for this work, though it also struck deals with transportation companies and community groups that wished to support the immigration of European women for domestic employment. In the period after World War II, the government began to openly recruit women for domestic work from a list of preferred European origins. For example, in little over a decade (1951-1963) over 10,000 Greek women became Canadian immigrants through such a scheme.[4] Since the 1970s, the government has moved to a system whereby women recruited to perform domestic or caregiver work in Canada will not necessarily receive immigrant status. Rather, recruitment schemes targeting women in the Philippines or certain Caribbean countries, for example, have been structured around term employment contracts that provide the migrants with limited support and no certain future in Canada.[5]

Key Points

- Female immigrants have been treated by many administrations as a separate category of recruit and applicant.

- The ways in which prospective immigrants were interrogated for eligibility was gendered.

- Class prejudices and ethnic biases combined to create particular niches for immigrant females, specifically in areas of work that did not appeal to Canadian women because of low pay or poor working conditions.

Media Attributions

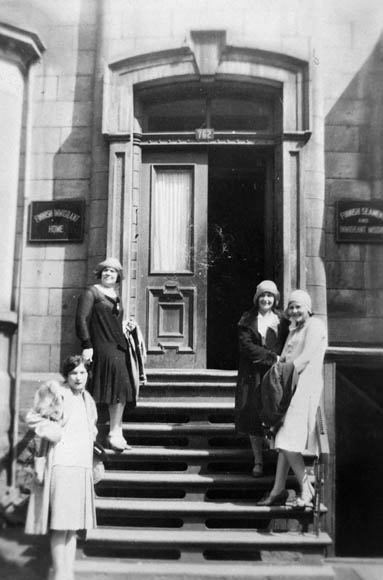

- Four women on steps of Finnish immigrant home, ca. 1929 © Victor Kangas, Library and Archives Canada (PA-127086) is licensed under a Public Domain license

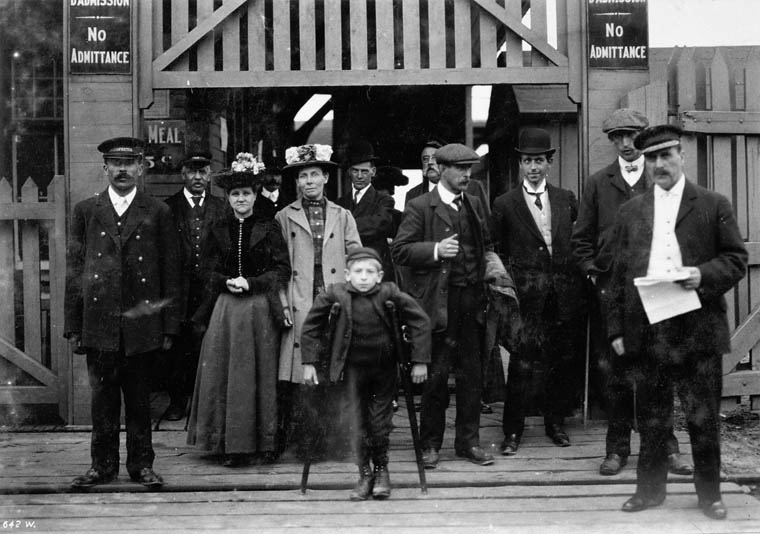

- Immigrants to be deported, 1912 © William James Tople, Library and Archives Canada (PA-020910) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Lisa Chilton, Agents of Empire: British Female Migration to Canada and Australia, 1860s-1930 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007); Marilyn Barber, Immigrant Domestic Servants in Canada (Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association, 1991). ↵

- Rebecca Mancuso, "Work 'Only a Woman Can Do': The Women's Division of the Canadian Department of Immigration and Colonization," The American Review of Canadian Studies (Winter 2005): 593-620. ↵

- For the late 19th and early 20th centuries, see Mariana Valverde, The Age of Light, Soap and Water: Moral Reform in English Canada, 1885-1925 (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1991). For the post-World War Two period, see Franca Iacovetta, Gatekeepers: Reshaping Immigrant Lives in Cold War Canada (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2006). ↵

- Noula Mina, "Taming and Training Greek 'Peasant Girls' and the Gendered Politics of Whiteness in Postwar Canada: Canadian Bureaucrats and Immigrant Domestics, 1950s-1960s," Canadian Historical Review, 94:4 (Dec. 2013): 514-39. ↵

- Abigail Bakan and Daiva Stasiulis, Negotiating Citizenship: Migrant Women in Canada and the Global System (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005). ↵