Chapter 11. First Nations from Indian Act to Idle No More

11.7 From Agricultural Training to Residential School

Jennifer Pettit, Department of Humanities, Mount Royal University

By the time the numbered treaties and the reserve system were created, Indigenous peoples in what is now Western Canada faced dire conditions. Many communities were ravaged by diseases such as smallpox, and devastated by the whisky trade. The bison, on which they relied, was almost extinct.[1] The Canadian government once again decided that the solution was model farms to accompany a policy of peasant farming through which Indigenous families were to receive “2 acres and a cow” — and through which they were not encouraged to utilize any labour-saving machinery. The government felt this would ensure Indigenous peoples would be converted to sedentary farmers, but would not be so successful that they would compete with the new settlers moving west. Not surprisingly, the plan failed. Government bureaucrats at the time blamed the supposed “lazy” nature of First Nations peoples. Historian Sarah Carter has since proven that Indigenous peoples were interested in farming, but that the government’s policies and practices undermined reserve agriculture.[2] More important to the government was a new system of schools for Indigenous children.

Though they had weak results in the early schools in central Canada, the Federal Government was optimistic that expanding schools into the Prairies made sense, hopeful that the Indigenous peoples there could also be “civilized and Christianized.”[3] Starving and destitute, some Indigenous peoples also hoped the schools would teach their children the skills necessary to adapt to changing conditions and, ideally, to learn a trade that would make them self-supporting. What remained to be determined though was what kind of education system would best serve the Indigenous peoples living in the West. To help answer that question in 1879, the government enlisted Nicholas Flood Davin (1840-1901), a Regina newspaper editor and the M.P. for Assiniboia West, to study the American system of industrial schools for Indigenous peoples. Notably, as was the pattern in government dealings with Indigenous peoples, Davin did not consult First Nations. He concluded that industrial schools in which children learned a trade and which were similar to those in the United States would be appropriate and useful in the West, despite disappointing results in similar schools in Central Canada. Davin also suggested that the Canadian government forge alliances with the churches to manage the schools.[4] These “industrial” schools were costly, however, and as a result, a parallel system of day and boarding schools was also created. Boarding schools were similar to the industrial schools, but were typically smaller with a much reduced focus on trades instruction. The first of the industrial schools — the Qu’Appelle Industrial School and the Battleford Industrial School located in the future province of Saskatchewan, and the St. Joseph’s School (also known as the High River or Dunbow school) southwest of Calgary — opened in the 1880s. These schools would lay the groundwork for a system of schools that would eventually spread across the Prairies and into British Columbia and the North.

By the time the last school closed in 1996, over 130 would have operated and over 150,000 Indigenous children would have been forced to attend what would ultimately be deemed tools of cultural genocide.[5] Indigenous children were taken from their homes, separated from their communities and families, and were forbidden to speak their languages or practice their culture. Students were poorly fed; subjected to medical experiments; forced to undertake manual labour; and were subjected to physical, sexual, and mental or spiritual abuse.[6] The legacy of this appalling treatment is still being felt in Indigenous communities today.[7]

To ensure the schools “succeeded,” the government enacted a number of measures including compulsory attendance in 1894 (and reinforced in further legislation in 1920). However, the parents of Indigenous students were not passive participants in the plans of church and state to “civilize” their children, and many did whatever they could to prevent their children from attending these schools and to demonstrate their displeasure. Parents were angered that their children were being abused and that they were taken so far away from the reserves. Parents were also upset that students were alienated from their culture, were forced to work long hours, were not properly cared for, and could not find employment after graduation. This opposition took place, however, in a power relationship in which Aboriginal peoples were unable to bring about real change. Thus, their opposition had only a limited effect. What did sway the administrators was rising costs.

Originally thought to be a quick and relatively inexpensive way to deal with what administrators deemed the “Indian Problem,” the schools had evolved into a costly and complicated system that was not producing significant results. As a consequence, Duncan Campbell Scott (1862-1947), who was appointed to the position of Superintendent of Indian Education in 1909, changed the professed goal of schools for Indigenous peoples from integration to segregation (in the words of Scott: “for civilized life in his own environment”). In 1923 officials merged the industrial and boarding schools to create a new category of schools known as “residential schools.”[8] Scott, though, still very much believed in a policy in which Indigenous peoples should be obliterated as a distinct community. In 1920 he made this now famous statement: “I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that the country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone.… Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question….”[9]

Key Points

- Setting Aboriginal people down the path to become European-style agriculturalists was underfunded and purposely organized to ensure they did not compete with European newcomers on the Prairies.

- Canadian-organized schools appealed to Aboriginal people because they held out the hope of skills and opportunities that would help their people escape poverty.

- The industrial schools were augmented by boarding schools in which industrial skills were minimized, the clergy were heavily involved, and costs were managed by obliging the children/pupils to do maintenance work.

- Compulsory attendance was legislated in 1894, enabling the abduction of children from their parents by the local Canadian authorities.

- By 1909 the objectives of the schools had changed again from integration to segregation and the combination of industrial and boarding schools to produce residential schools. Superintendant Duncan Campbell Scott believed that Aboriginal peoples could never occupy an equitable position in Canadian society and was satisfied to use the schools to build a marginalized people.

Media Attributions

- Numbered Treaties Map is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

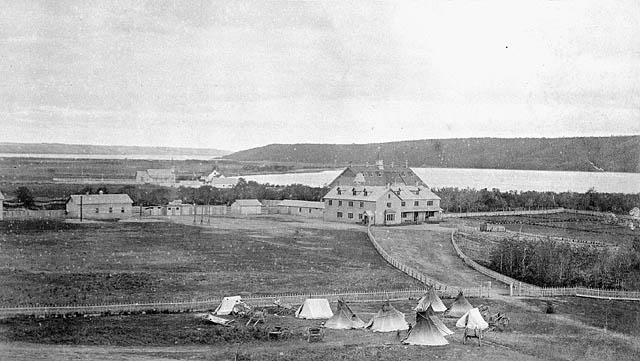

- Distant view of Fort Qu’Appelle Indian Industrial School with tents, [Red River] carts and teepees outside the fence © O.B. Buell, Library and Archives Canada (PA-182246) is licensed under a Public Domain license

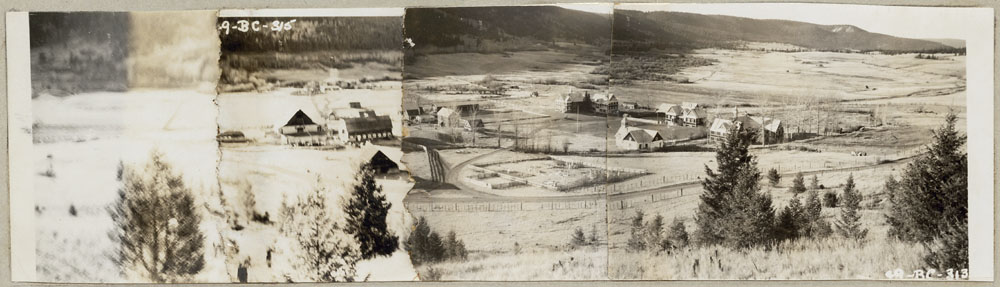

- Panorama of Cariboo Indian Residential School, William’s Lake, British Columbia, 1949 © Canada Dept. of Indian and Northern Affairs, Library and Archives Canada (MIKAN no. 4674075) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- See James Daschuk, Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life (Regina, SK: University of Regina Press, 2013). ↵

- See Sarah Carter, Lost Harvests: Prairie Indian Reserve Farmers and Government Policy (Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1990). ↵

- See J. R. Miller, Shingwauk’s Vision: A History of Native Residential Schools (Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 1996) and John Milloy, A National Crime: The Canadian Government and the Residential School System, 1879 to 1986 (Winnipeg, MB: University of Manitoba Press, 1999). ↵

- Canada, Report on Industrial Schools for Indians and Half-Breeds by Nicholas Flood Davin. 14 March, 1879. Library and Archives Canada, Record Group 10, Vol. 6001, File 1-1-1. ↵

- Canada, Truth and Reconciliation Commission, "Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada" [PDF], last modified July 23, 2015, http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2015/trc/IR4-7-2015-eng.pdf ↵

- Ian Mosby, “Administering Colonial Science: Nutrition Research and Human Biomedical Experimentation in Aboriginal Communities and Residential Schools, 1942-1952,” Histoire sociale/Social History 46, no. 91 (2013): 615-642. ↵

- Canada, Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Vol. 5: Renewal: A Twenty-Year Commitment. In For Seven Generations: An Information Legacy of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples [CD-ROM] (Ottawa: Libraxus, 1997.) ↵

- Brian Titley, A Narrow Vision: Duncan Campbell Scott and the Administration of Indian Affairs in Canada (Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press, 1986). ↵

- Duncan Campbell Scott, Deputy Superintendent General of Indian affairs, testimony before the Special Committee of the House of Commons examining the Indian Act amendments of 1920, Library and Archives Canada, Record Group 10, vol. 6810, file 470-2-3, volume 7, pp. 55 (L-3) and 63 (N-3). ↵