Chapter 6. The War Years, 1914–45

6.15 The Home Front

As was the case in what was now described as the “First World War” or “World War I,” the Second World War called for sweeping civilian resources and involvement. The lessons of 1914-1918 were near enough in people’s memories that the idea of Victory Bonds or women working in munitions factories needed little introduction. It is unlikely that “Rosie the Riveter” did the same job in both wars, but entirely feasible that she was doing the sort of work in the 1940s that her mother, or at least women of her mother’s generation, performed two decades earlier.

The extent of Canadians’ engagement in the war was largely a function of numbers. Out of a population of 11 million, only 8 million were over the age of 18 years. This was not enough to meet both the need for a million-man army and the rapid increase in demand for food exports and munitions headed for Britain. Able-bodied men were forced out of what were now regarded as non-essential jobs (like taxi driving, the production of sporting goods, and the sale of real estate) so that they could tackle war industries or service in the forces.[1] Conscription might be an issue that the government wished to avoid but enlisting workers from non-traditional sources was a task they hurried to manage.

Women in Industry

In March 1942, Ottawa took the unprecedented step of registering every woman born between 1918 and 1922 under an order-in-council called the National Selective Service Regulations. (Similar orders were passed that identified and regulated men from 17 to 70 years of age, and ensured that key industries — including school teaching — would not be abandoned by workers too eager to join up or find better paying work as it came along.) Within a year there were 373,000 women in manufacturing jobs (of which 261,000 worked in munitions) and another 439,000 in the service sector. Nearly one-in-three workers in Canada’s aviation industry — mostly dedicated at this time, of course, to fighter and transport aircraft — were women.[2] Overall it has been reckoned that there were more than a million women in the full-time workforce, and that figure does not include women in the agricultural sector, nor does it include women in part-time paid labour.[3]

One area of spectacular expansion was shipbuilding. The collapsed economy of the 1930s witnessed a running down of capacity along the nation’s waterfronts. It was thought that there were, on the eve of the war, three active shipyards in the whole country and these employed fewer than 4,000 men. This expanded to 90 yards employing over 126,000 women and men.[4] Shipyards in wartime Vancouver alone employed some 17,000 workers — perhaps half of them women — and the several slipways were launching a Victory Ship a week between them. The Canadian fleet was, by the end of the war, probably the 5th largest on earth, a position onto which it would not hold.

The war opened opportunities, too, for women at levels above the shop floor. Probably the best known and most honoured example is Elsie “Queen of the Hurricanes” MacGill (1905-80), the world’s first female aeronautical engineer. She was the daughter of a prominent lawyer father and a feminist/suffragette mother — Helen Gregory MacGill — who was a pioneer woman on the British Columbian bench. Elsie MacGill’s transition into management of the Canadian Car and Foundry company put her in charge of a mainly female workforce that churned out more than 1,400 fighter aircraft (Hawker Hurricanes) before the end of the war.

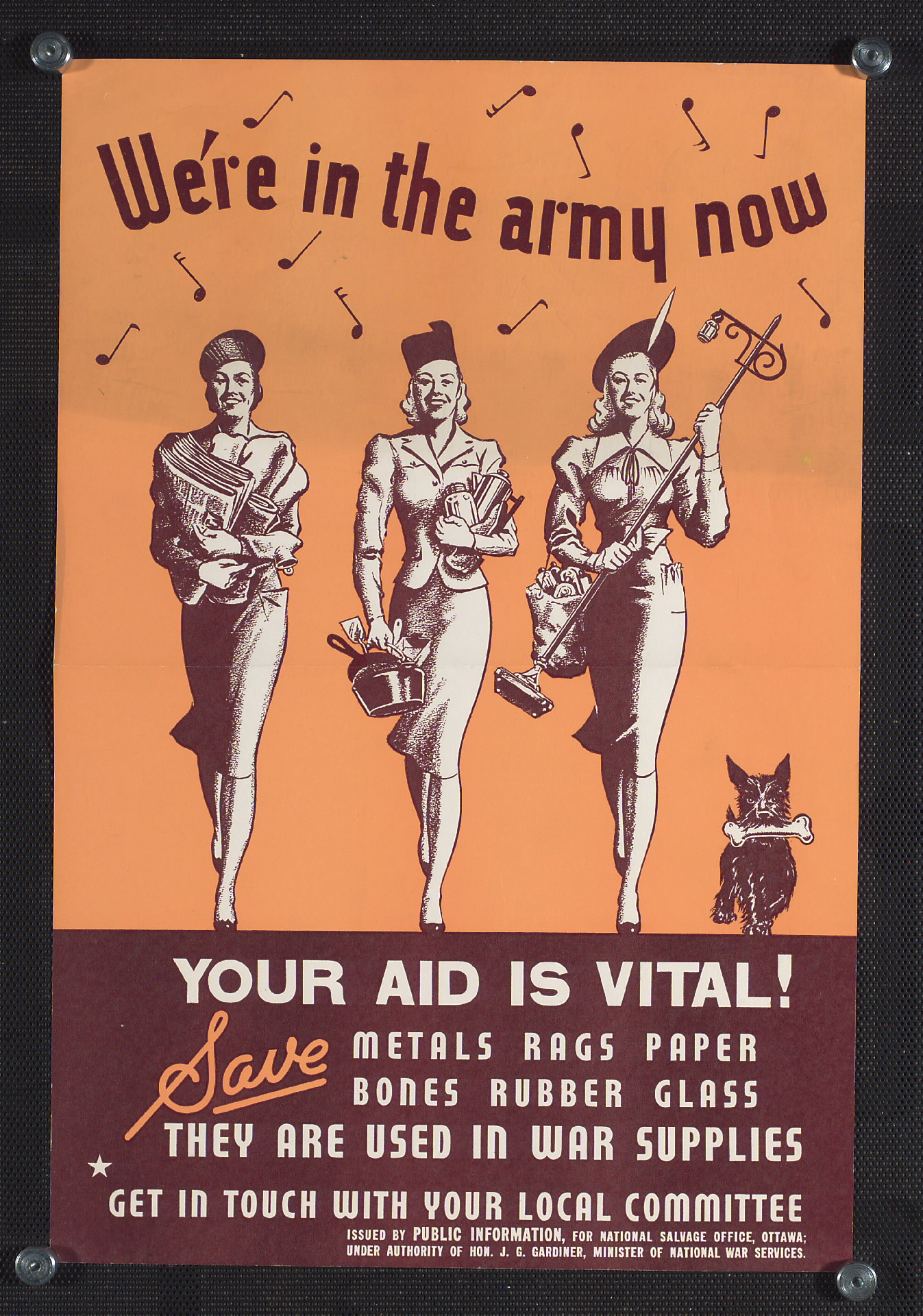

Sea blockades meant that raw materials necessary to war industries were feared to be in jeopardy from 1939 on. Women were tasked with organizing scrap drives, salvaging metals and rubber in particular but also kitchen scraps. Bones and fat — used in the production of ammunition — were a special target; scavenging families in Winnipeg accumulated more than a million pounds of fat and bones over the course of the war.[5] In practice, it was the children of urban areas who took the lead on salvage crusades, rather naturally lending it a competitive flavour.

The careful management of resources extended to the food supply. Britain’s trade corridors were cut off so Canadian food production had to increase (difficult to do in times of labour shortages) and more had to be diverted to exports. As early as 1941, Canada was providing 77% of Britain’s flour and wheat. By the end of the war a quarter of the cheese, two-fifths of the bacon, and 15% of the eggs consumed in Britain came from Canadian farms.[6] While the Wartime Prices and Trade Board (WPTB) established limits on consumption and price-gouging, Ottawa’s various agencies encouraged Canadians to turn their gardens into small farms.

Canadians could feel the war in their stomachs and see it on their plates. They could also wear the war effort because of restrictions on fabric for clothing. Excessive trim was pared back, leading to narrower lapels on men’s suits and a narrower cut on women’s clothes along with shorter hems. One explanation for the so-called zoot suit riots of the closing years of the war was the apparent — and unpatriotic — use of too much cloth on the exaggerated shoulders and thighs of the zoot suiters’ eponymous jackets and trousers. (The fact that Vancouver’s zoot suiters were mainly drawn from the Italian community in the East End may have been another local factor.)[7]

Wartime Cultures

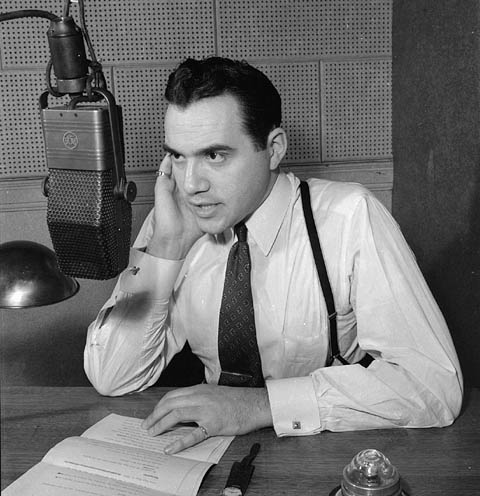

While escapism defined much of the entertainment produced in the 1930s, the war provided subject matter galore. Canadian comic books enjoyed a brief period of popularity as competitive American publications were frozen out of the market. The most successful of these, Johnny Canuck, appeared in 1941 but did not survive the war years. Hollywood movies had all but completely superseded vaudeville by 1939; feature films and short (generally cheaply made) serials were an important means of transmitting anti-German and anti-Japanese sentiment. They sometimes featured Canadian characters (usually played by Americans) so as to give American audiences a sense of the role played by allies. The 1943 war-thriller, Northern Pursuit, featured the great matinee idol and action actor, Errol Flynn, portraying a Mountie who captures German saboteurs determined to disrupt Canadian-American supply lines. What is noteworthy about this film is that Flynn plays a German-Canadian whose ethnicity draws the suspicion of his RCMP colleagues until his loyalty to Canada is made clear. The Canadian film industry, small though it was, produced propaganda-inflected films, including the National Film Board’s Canada Carries On series (many of which were narrated by Lorne Greene). Warclouds over the Pacific, for example, was released on 1 December 1941, days before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, but it made clear Canada’s official perspective on the dangers coming from that direction.

Radio was, in the 1930s and 1940s, at its peak as an electronic media. The presence of the CBC at this time provided another — government-controlled — means of being bombarded with news about the war and further demands for personal sacrifice. Radio waves were not as respectful of borders as print media, so American programming and propaganda was part and parcel of most urban Canadians’ listening diet.

Many of these media traded in fear as a means of whipping up support for the war. Routine precautions — training children on the east and west coast on what to expect in the event of a surprise German or Japanese attack, or the mandatory use of black-out blinds and headlamp covers so as to confuse aerial scouts from Japan — added to the sense that there was real danger nearby and not only on the war front.

In a multitude of ways, then, the Second World War certainly felt more like a total war. It was impossible to avoid news, film, rationing, restrictions, admonitions, salvage drives, calls for volunteers, and requests for more Victory Bonds. Canadians experienced it with a mixture of emotions, though, including grateful relief that the Depression years were finally over (although fearful they might return). Full employment — even at a time of rationing and very little in the way of consumer goods to purchase — was a good thing.

Key Points

- As a total war, WWII made greater demands on Canadians on the home front than was the case in 1914-18.

- Ottawa introduced regulations to manage the supply of labour and to ensure the continuation of essential industries.

- Women entered waged labour in war industries in large numbers, taking jobs that were vacated by servicemen and newly created positions as well.

- Scrap drives were a means of obtaining scarce materials and directly involving women and children in the war effort.

- Film and radio — both mostly interwar innovations — contributed significantly to the propaganda campaign.

Long Descriptions

Figure 6.27 long description: Poster from World War II. It depicts three women in skirts and blouses marching down the street with broad smiles. One holds newspapers; another holds a skillet and a kettle; the third holds a bag on her arm and a broom in her hands instead. A Scottish terrier trots alongside the women with a bone in its mouth.

At the top, the poster says “We’re in the army now,” surrounded by musical notes to indicate that the women are singing these words. At the bottom, it says “Your aid is vital! Save metals, rags, paper, bones, rubber, glass. They are used in war supplies. Get in touch with your local committee. Issued by Public Information, for National Salvage Office, Ottawa; under authority of Hon. J. G. Gardiner, Minister of National War Services.” [Return to Figure 6.27]

Media Attributions

- Attack on all Fronts: war propaganda campaign — World War II © Library and Archives Canada (MIKAN no. 2860024) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Shop Stewards at Burrard Drydock, ca. 1942 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Elsie MacGill, April 1938 is licensed under a Public Domain license

- We’re in the Army Now © Toronto Public Library (1939-45. Salvage. Item 12. L) is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Commentator Lorne Greene broadcasting over the C.B.C. national network, Dec. 1942 © Ronny Jaques, National Film Board of Canada, Library and Archives Canada (PA-116178) is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Desmond Morton, A Military History of Canada, 5th edition (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2007), 184-5. ↵

- Canadian War Museum, “Democracy at War”, accessed 15 November 2015, http://www.warmuseum.ca/cwm/exhibitions/newspapers/canadawar/women_e.shtml. ↵

- Ruth Roach Pierson, "They're Still Women After All," The Second World War and Canadian Womanhood (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1986): 9. ↵

- Canadian War Museum, “Democracy at War”, accessed 16 November 2015, http://www.warmuseum.ca/cwm/exhibitions/newspapers/canadawar/shipping_e.shtml. ↵

- Ian Mosby, “Food on the Home Front during the Second World War”, Wartime Canada, accessed 15 November 2015, http://wartimecanada.ca/essay/eating/food-home-front-during-second-world-war. ↵

- Ian Mosby, Food Will Win the War: The Politics, Culture, and Science of Food on Canada’s Home Front (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2014), 4. ↵

- ”Zoot Suit Riots,” Past Tense: Vancouver History, Lani Russwurm, accessed 17 November 2015, https://pasttensevancouver.wordpress.com/2008/03/03/zoot-suit-riots-2/. ↵