9.7 Pulse

What Is Pulse?

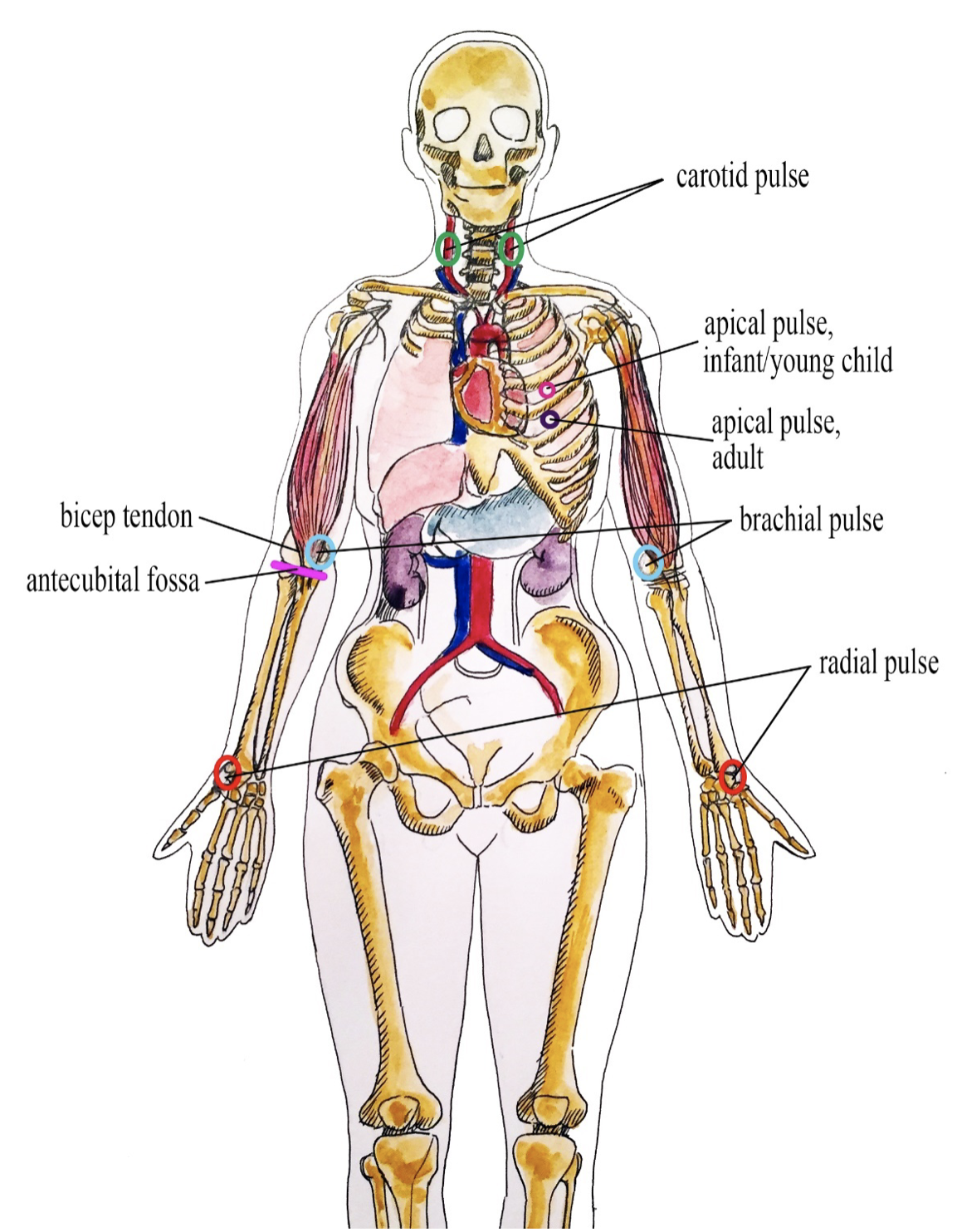

Pulse refers to a pressure wave that expands and recoils the artery when the heart contracts/beats. It is palpated at many points throughout the body. The most common locations to accurately measure pulse as part of vital sign measurement include radial, brachial, carotid, and apical pulse as shown in Figure 9.7.1 The techniques vary according to the location, as detailed later.

The heart pumps a volume of blood per contraction into the aorta. This volume is referred to as stroke volume. Age is one factor that influences stroke volume, which ranges from 5–80 mL from newborns to older adults.

Pulse is measured in beats per minute, and the normal adult pulse rate (heart rate) at rest is 60–100 beats per minute. Newborn resting heart rates range from 100–175 beats per minute (bpm). Heart rate gradually decreases until young adulthood and then gradually increases again with age. A pregnant person’s heart rate is slightly higher than the pre-pregnant value (about 15 beats). See Table 9.7.1 for normal heart rate ranges based on age.

| Age | Heart rate (beats per minute) |

|---|---|

| Newborn to one month | 100–175 |

| One month to two years | 90–160 |

| Age 2–6 years | 70–150 |

| Age 7–11 years | 60–130 |

| Age 12–18 years | 50–110 |

| Adult and older adult | 60–100 |

Points to Consider

The ranges noted in Table 9.7.1 are generous. It is important to remember that the role of the Health Care Assistant is to take the pulse measurement and record and report. The nurse will consider each client and situation to determine whether the heart rate is normal. For example, heart rate is considered in the context of a client’s baseline heart rate. The nurse also considers the client’s health and illness state and determinants such as rest/sleep, awake/active, and presence of pain. You can expect higher pulse values when a client is in a stressed state such as when crying or in pain; this is particularly important in the newborn. It is best to measure the vital signs when the client is in a resting state. If you obtain a pulse when the client is not in a resting state, document the circumstances (e.g., stress, crying, or pain) and retake the measurements as needed.

Why Is Pulse Measured?

Health care providers measure pulse because it provides information about a client’s state of health and influences diagnostic reasoning and clinical decision-making.

Tachycardia

Tachycardia refers to an elevated heart rate, typically above 100 bpm for an adult. Developmental considerations are important to consider, such as higher resting pulse rates in infants and children. For adults, tachycardia is not normal in a resting state but may be detected in pregnant people or individuals experiencing extreme stress. Tachycardia can be benign, such as when the sympathetic nervous system is activated with exercise and stress. Caffeine intake and nicotine can also elevate the heart rate. Tachycardia is also correlated with fever, anemia, hypoxia, hyperthyroidism, hypersecretion of catecholamines, some cardiomyopathies, some disorders of the valves, and acute exposure to radiation.

Bradycardia

Bradycardia is a condition in which the resting heart rate drops below 60 bpm in adults. In newborns, a resting heart rate below 100 bpm is considered bradycardia. However, a sleeping neonate’s pulse may be as low as 90 bpm. People who are physically fit (e.g., trained athletes) typically have lower heart rates. If the client is not exhibiting other symptoms, such as weakness, fatigue, dizziness, fainting, chest discomfort, palpitations, or respiratory distress, bradycardia is generally not considered clinically significant. However, if any of these symptoms are present, this may indicate that the heart is not providing sufficient oxygenated blood to the tissues. Bradycardia can be related to an electrical issue of the heart, ischemia, metabolic disorders, pathologies of the endocrine system, electrolyte imbalances, neurological disorders, prescription medications, and prolonged bedrest, among other conditions. Bradycardia is also related to some medications, such as beta blockers and digoxin.

What Pulse Qualities Are Observed?

The pulse rhythm, rate, force, and equality are observed when palpating pulses.

Pulse Rhythm

The normal pulse rhythm is regular, meaning that the frequency of the pulsation felt by your fingers follows an even tempo with equal intervals between pulsations. If you compare this to music, it involves a constant beat that does not speed up or slow down, but stays at the same tempo. Thus, the interval between pulsations is the same. However, sinus arrhythmia is a common condition in children, adolescents, and young adults. Sinus arrhythmia involves an irregular pulse rhythm in which the pulse rate varies with the respiratory cycle: the heart rate increases at inspiration and decreases back to normal upon expiration. The underlying physiology of sinus arrhythmia is that the heart rate increases to compensate for the decreased stroke volume from the heart’s left side upon inspiration.

Pulse Rate

The pulse rate is counted by starting at one, which correlates with the first beat felt by your fingers. Count for 30 seconds if the rhythm is regular (even tempo) and multiply by two to report in beats per minute. Count for one minute if the rhythm is irregular. In children, pulse is counted for one minute considering that irregularities in rhythm are common.

Pulse Force

The pulse force is the strength of the pulsation felt when palpating the pulse. For example, when you feel a client’s pulse against your fingers, is it gentle? Can you barely feel it? Alternatively, is the pulsation very forceful and bounding into your fingertips? The force is important to observe because it reflects the volume of blood, the heart’s functioning and cardiac output, and the arteries’ elastic properties. Remember, stroke volume refers to the volume of blood pumped with each contraction of the heart (i.e., each heart beat). Thus, pulse force provides an idea of how hard the heart has to work to pump blood out of the heart and through the circulatory system.

Pulse force is recorded using a four-point scale:

- 3+ full, bounding

- 2+ normal/strong

- 1+ weak, diminished, thready

- 0 absent/non-palpable

Practise on many people to become skilled in measuring pulse force. While learning, it is helpful to observe pulse force along with an expert because there is a subjective element to the scale. A 1+ force (weak and thready) may reflect a decreased stroke volume and can be associated with conditions such as heart failure, heat exhaustion, or hemorrhagic shock, among other conditions. A 3+ force (full and bounding) may reflect an increased stroke volume and can be associated with exercise and stress, as well as abnormal health states including fluid overload and high blood pressure.

Pulse Equality

Pulse equality refers to whether the pulse force is comparable on both sides of the body. For example, palpate the radial pulse on the right and left wrist at the same time and compare whether the pulse force is equal. Pulse equality is observed because it provides data about conditions such as arterial obstructions and aortic coarctation. However, the carotid pulses should never be palpated at the same time as this can decrease and/or compromise cerebral blood flow.

These are the upper body pulse points that will be covered in the following sections.

Radial Pulse Technique

Use the pads of your first three fingers to gently palpate the radial pulse. The pads of the fingers are placed along the radius bone, which is on the lateral side of the wrist (the thumb side; the bone on the other side of the wrist is the ulnar bone). Place your fingers on the radius bone close to the flexor aspect of the wrist, where the wrist meets the hand and bends. See Figure 9.7.2 for correct placement of fingers. Press down with your fingers until you can best feel the pulsation. Note the rate, rhythm, force, and equality when measuring the radial pulse.

Technique Tips

Note the first beat felt in your fingers as “1” and then continue to count. Alternatively, start counting at “0” when your watch is at zero and then continue to count.

What Should the Health Care Assistant Consider?

You may need to adjust the pressure of your fingers when palpating the radial pulse if you cannot feel the pulse. For example, sometimes pressing too hard can obliterate the pulse (make it disappear). Alternatively, if you do not press hard enough, you may not feel a pulse. You may also need to move your fingers around slightly. Radial pulses are difficult to palpate on newborns and children under five, so health care providers usually use the apical pulse or brachial pulse of newborns and children.

Watch this YouTube video on how to Take a Radial Pulse and Respirations

Radial Pulse / Respiration – Taken Correctly by Toronto Metropolitan University.

Exercises

Pulse refers to:

- The volume of blood that moves through the artery when the heart contracts/beats

- The volume of blood that moves through the vein when the heart contracts/beats

- The pressure wave that expands and recoils the vein when the heart contracts/beats

- The pressure wave that expands and recoils the artery when the heart contracts/beats

The pulse found in the radial artery between the wrist bone and the tendon on the thumb side of the wrist.

The pulse found on the inner aspect of the upper arm.

Two main arteries that carry blood to the head and neck.

The pulse found on the chest at the bottom tip or apex of the heart.

The main artery that carries oxygenated blood away from the heart.

Blood vessels that bring oxygen-rich blood from the heart to the body cells and tissues.