2.6 Point-of-Care Risk Assessment (PCRA)

Point-of-care risk assessment (PCRA) is performed by all health care workers to determine the appropriate infection prevention and control measures for safe client care and to protect the worker from exposure to microorganisms. Remember how infections are spread, as this can help you perform a better PCRA and break the chain of infection.

Prior to every client interaction, you, as an HCA, have a responsibility to evaluate the infectious risk posed to yourself and other clients, visitors and workers by a client, situation, or procedure. The PCRA is an evaluation of the risk factors related to the interaction between you, the client, and the client’s environment to evaluate their potential for exposure to infectious agents and identify risks for transmission.

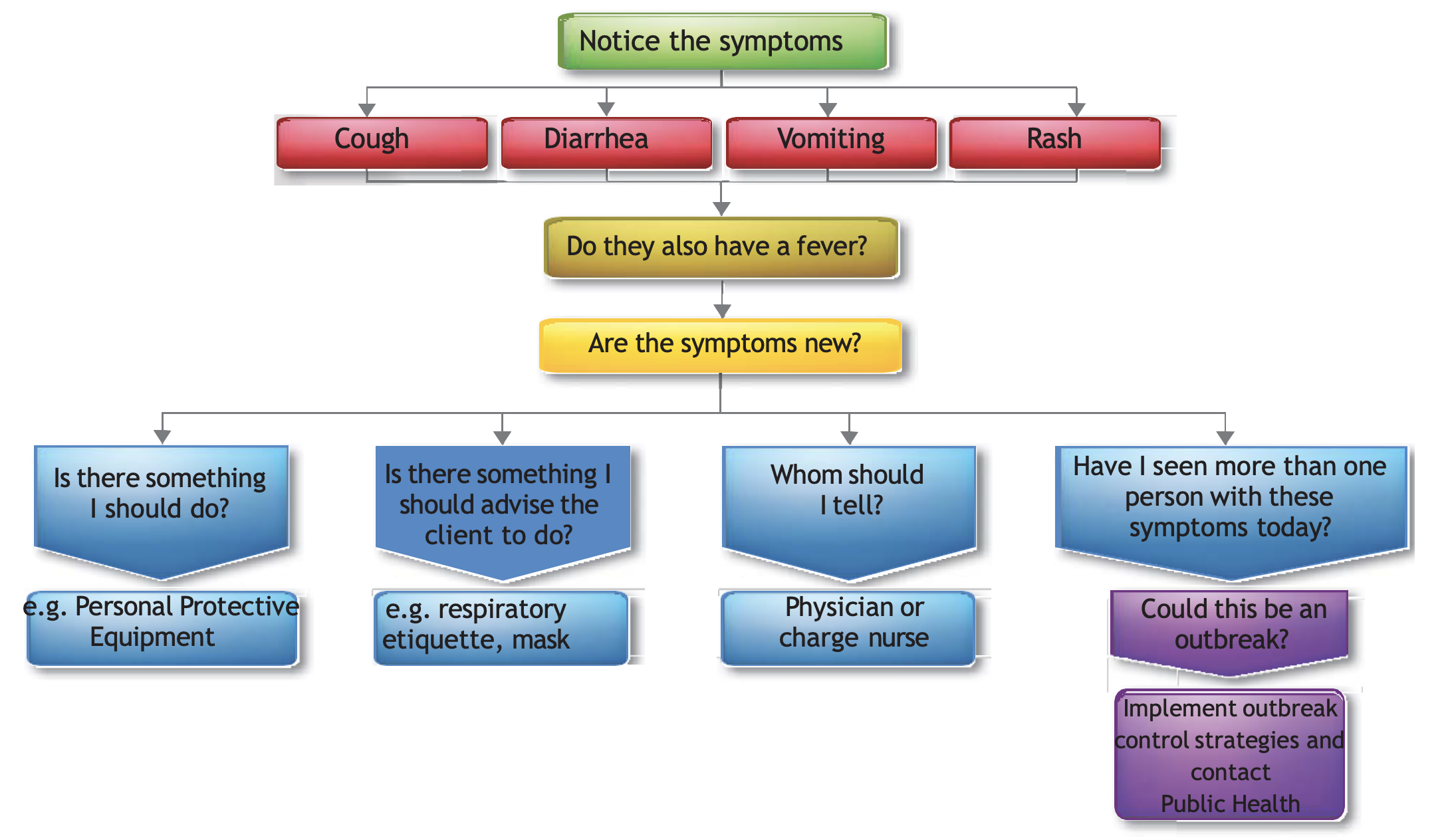

PCRA is when you evaluate the risk involved in providing care to a client who appears sick, or letting them interact with other clients. It may sound complicated, but in reality, health care workers conduct point-of-care risk assessments and observations of the client’s health status many times a day, often without thinking about it. For example, when you approach a client, you automatically note their mental status, ease of breathing, skin colour, etc. An infection control PCRA is simply an extension of this. The following section offers some questions to consider and Figure 2.6.1 shows the steps for deciding on the precautions you would take.

PCRA Questions to Ask Yourself

Ask yourself the following questions before and during a PCRA:

- What contact will I have with the client? (direct hands-on care vs. no hands-on care; contact with mucus membranes or non-intact skin)

- What care activities am I going to perform? Is there a risk of splashes/sprays? Likely to stimulate a cough? Or gagging?

- If the client has diarrhea, are they continent? If incontinent, can stool be contained in an adult incontinence product?

- Is the client able and willing to perform hand hygiene? Or respiratory hygiene (covering their cough/sneeze)?

- Is the client able to follow instructions?

- Is the client in a shared room? Is there a better room/space that I should use to provide this care?

- Is there personal protective equipment that I should put on prior to this care activity?

Who Should Do PCRAs?

Everyone that interacts with clients should be doing PCRAs. It can be as simple as noting if they’re coughing today when they weren’t yesterday. Health care workers should routinely perform PCRAs throughout the day to apply control measures for their safety and the safety of clients and others in the health care environment.

For example, a PCRA is performed when a health care worker evaluates a client’s situation to:

- Determine the priority for single rooms, or for roommate selection, if rooms are to be shared by clients.

- Determine the possibility of exposure to blood, body fluids, secretions and excretions and non-intact skin, and select appropriate control measures (e.g., PPE) to prevent exposure.

- Determine the need for additional precautions when routine practices are inadequate to prevent exposure.

Have a look at Table 2.6.1 that uses Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) as an example of infection with contact spread to better understand the PCRA you might use in your work. It provides you with greater understanding of what would be higher risk, and helps you make better choices for the need of additional precautions to go along with your routine practices.

| Source | Higher transmission risk | Lower transmission risk |

|---|---|---|

| Infectious agent/infected source | Frequent diarrhea | Formed stools |

| Incontinence | Continence | |

| Poor hygiene | Good hygiene | |

| Not capable of self-care due to physical condition, age, or cognitive impairment | Capable of self-care | |

| Environment | High patient/client nurse ratio | Low patient/client nurse ratio |

| Shared bathroom, shared sink | Single room, private in-room toilet, designated patient/client handwashing sink | |

| Shared commode without cleaning between patients/clients | Dedicated commode | |

| No hand hygiene at point-of-care | Hand hygiene at point-of-care | |

| No designated staff handwashing sink or sink is used for other purposes or sink is dirty | Accessible, designated, clean staff handwashing sink | |

| Inadequate housekeeping | Appropriate housekeeping | |

| Susceptible host (patient/client) | Receiving direct patient/client care | Capable of self-care |

| Poor personal hygiene | Good personal hygiene |

Additional Precautions Practices

Another practice used in health care is the use of additional precautions. Additional precautions are usually determined by the infection control team (Perry et al., 2014). When a client is suspected of having or is confirmed to have certain pathogens or clinical presentations, additional precautions are implemented by the health care worker in addition to routine practices (PIDAC, 2012).

The type of additional precautions to use along with the routine precautions will depend on how the particular pathogen is spread and this will determine the type of additional precautions to be used. There are generally three types of infection spread that require consideration for additional precautions: Contact, Droplet, and airborne. For example, Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) requires contact precautions as the bacteria is spread by both direct and indirect contact. The infection control team will advise which additional precautions staff will use. Table 2.6.2 provides you with some examples you will likely see in your practice and to understand when additional precautions are used.

Some infections may need a combination of additional precautions (contact, droplet, airborne) since some microorganisms can be transferred by more than one route. Regardless of the additional precautions, you still need to use the routine practices even with the additional precautions.

| Contact Transmission | Droplet Transmission | Airborne Transmission | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precautions |

|

|

|

| Common infections |

|

|

|

| Examples of symptoms |

|

|

|

Summary

- Following infection preventative and control practices and guidelines prevents or stops the spread of infections to health care workers, clients, and visitors.

- Infection prevention and control starts with good hand hygiene!

- Infection prevention and control practices guide health care workers to practise safely. Using routine practices and conducting point-of-care risk assessments can eliminated the transmission of microorganisms and knowing how and where to use additional precautions can help you as an HCA to stop the spread of infection.

Image descriptions

Figure 2.6.1 PCRA Decision Algorithm

The following is a flowchart PiCNET (2014, p. 15) describes the decision-making process around PCRA:

- Notice the Symptoms

- Cough

- Diarrhea

- Vomiting

- Rash

- Do they also have a fever?

- If yes, are the symptoms new?

- If yes:

- Is there something I should do? E.g., personal protective equipment.

- Is there something I should advise the client to do? E.g. respiratory etiquette, or mask.

- Who should I tell? E.g., physician or charge nurse.

- Have I seen more than one person with these symptoms today?

- Could this be an outbreak?

- Implement outbreak control strategies and contact Public Health

[Back to Figure 2.6.1]

Chapter 2 Attributions and References

Unit 2.2 Image Attributions

- Figure 2.2.1 Infections Spread Quickly! from PxHere, is used under a CC0 Public Domain licence.

- Figure 2.2.2 School Sores, or Impetigo, is Highly Contagious from PxHere, is used under a CC0 Public Domain licence.

-

Figure 2.2.3 Bacteria Infection from PxHere, is used under a CC0 Public Domain licence.

- Figure 2.2.4 Antibiotics Can Disrupt the Balance of Normal Pathogens from PxHere, is used under a CC0 Public Domain licence.

- Figure 2.2.5 The Chain of Infection by the Public Health Agency of Canada (2016), for non-commercial reproduction. Original created by Dr. Donna Moralejo, Associate Professor, Memorial University.

Unit 2.4 Image Attributions

- Figure 2.4.1 Left 4 Germs : One about scrubbing your hands… by tbSMITH, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence.

- Figure 2.4.2 Female hands with lunar black manicure by FineShine, via depositphotos.com , is used under an Attributed Free License.

- Figure 2.4.3 My boo-boo 3 by Thom Watson, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 license.

- Figure 2.4.4 Person Washing Hands by Anna Shvets, via Pexels, is used under the Pexels license.

- Figure 2.4.5 Wash Your Hands Thoroughly from PxHere, is used under a CC0 Public Domain licence.

- Figure 2.4.6 Dispenser Photo by Amanda Mills, USCDCP, via Pixnio, is used under a CC0 Public Domain licence.

- Figure 2.4.7 Question Mark Question Answer Search Engine Icon by Peggy_Marco, via Pixabay, is used under the Pixabay License.

- Figure 2.4.8 Five Moments of Hand Hygiene from WHO IPC Training tools, is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO license.

- Figure 2.4.9 Hand hygiene with ABHR by Doyle & McCutcheon (2015), via BCcampus, is used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- Figure 2.4.10 Remove gloves from box by Doyle & McCutcheon (2015), via BCcampus, is used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- Figure 2.4.11 Apply first glove by Doyle & McCutcheon (2015), via BCcampus, is used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- Figure 2.4.12 Apply second glove by Doyle & McCutcheon (2015), via BCcampus, is used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- Figure 2.4.13 Non-sterile gloved hands by Doyle & McCutcheon (2015), via BCcampus, is used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- Figure 2.4.14 Grasp glove on the outside 1/2 inch below the cuff by Doyle & McCutcheon (2015), via BCcampus, is used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- Figure 2.4.15 Pull glove off … by Doyle & McCutcheon (2015), via BCcampus, is used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- Figure 2.4.16 … inside out by Doyle & McCutcheon (2015), via BCcampus, is used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- Figure 2.4.17 Gather inside-out glove in remaining gloved hand by Doyle & McCutcheon (2015), via BCcampus, is used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- Figure 2.4.18 Insert finger under cuff of gloved hand by Doyle & McCutcheon (2015), via BCcampus, is used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- Figure 2.4.19 Remove second glove by Doyle & McCutcheon (2015), via BCcampus, is used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- Figure 2.4.20 Discard used non-sterile gloves by Doyle & McCutcheon (2015), via BCcampus, is used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- Figure 2.4.21 Hand hygiene with ABHR by Doyle & McCutcheon (2015), via BCcampus, is used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

Unit 2.5 Image Attributions

- Figure 2.5.1 personal protective equipment (PPE) from PxHere, is used under a CC0 Public Domain licence.

- Figure 2.5.2 Putting on (Donning) Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) by Alberta Health Services is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA license.

- Figure 2.5.3 Taking off (Doffing) Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) by Alberta Health Services is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA license.

Unit 2.6 Image Attributions

- Figure 2.6.1 PCRA Decision Algorithm from the Provincial Infection Control Network of BC (PICNet, 2014, p. 15), is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 licence.

- Table 2.6.1 PCRA Example Using C. Difficile is from Table 2 in the Public Health Agency of Canada (2016), via Government of Canada website, for non-commercial reproduction.

- Table 2.6.2 Additional Precautions PPE from the Provincial Infection Control Network of BC (PICNet, 2014, p. 18), is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 licence.

Videos

- Soap and Water by LearningHub (2022) is licensed under a Standard YouTube License.

- Alcohol Based Hand Rub by LearningHub (2022) is licensed under a Standard YouTube License.

- PPE Donning for Medical Mask by LearningHub (2022) is licensed under a Standard YouTube License.

- PPE Doffing for Medical Mask by LearningHub (2022) is licensed under a Standard YouTube License.

References

BC Centre for Disease Control (BCCDC). (2014). Hand hygiene. Retrieved from http://www.bccdc.ca/prevention/HandHygiene/default.htm.

Braswell, M. L., & Spruce, L. (2012). Implementing AORN recommended practices for surgical attire. AORN Journal, 95(1), 122-140. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2011.10.017.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2007). Part III: Precautions to prevent the transmission of infectious agents. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/2007IP/2007ip_part3.html.

Centers for Disease Control (CDC). (2012). Frequently asked questions about Clostridium difficile for health care providers. https://www.cdc.gov/HAI/organisms/cdiff/Cdiff_infect.html

Doyle, G. R., & McCutcheon, J. A. (2015, November 23 ). Clinical procedures for safer patient care. British Columbia Institute of Technology (BCIT)/ BCcampus. https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/

LearningHub. (2022, February 28). Alcohol based hand rub [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_WCzsSC18Io

LearningHub. (2022, February 28). PPE doffing for medical mask [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pL8blsiZfF8

LearningHub. (2022, February 28). PPE donning for medical mask [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FcCbvnxT0vI

LearningHub. (2022, February 28). Soap and water [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=19Rpe5wmqYE

Longtin, Y., Sax, H., Allegranzi, B., Schneider, F., & Pittet, D. (2011). Hand hygiene. New England Journal of Medicine, 34(13) 24–28. http://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMvcm0903599.

Patrick, M., & Van Wicklin, S. A. (2012). Implementing AORN recommended practices for hand hygiene. AORN Journal, 9(4), 492–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aorn.2012.01.019

Poutanen, S. M., Vearncombe, M., McGeer, A. J., Gardam, M., Large, G., & Simor, A. E. (2005). Nosocomial acquisition of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus during an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Infection control and hospital epidemiology, 26(2), 134–137. https://doi.org/10.1086/502516

Provincial Infection Control Network of British Columbia [PICNet]. (n.d.). Guidelines & toolkits. Provincial Health Services Authority (PHSA). https://www.picnet.ca/practice-guidelines

Provincial Infection Control Network of British Columbia [PICNet]. (2014). Infection control quick-reference guide for residential care facilities (Volume 2) [PDF]. PHSA. https://www.picnet.ca/resources/rescarebooklet/ www.picnet.ca/practice-guidelines

Perry, A. G., Potter, P. A., & Ostendorf, W. R. (2014). Clinical skills and nursing techniques (8th ed.). Elsevier-Mosby.

Provincial Infectious Diseases Advisory Committee (PIDAC). (2012). Routine practices and additional precautions in all health care settings (3rd ed.). Public Health Ontario. http://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/eRepository/RPAP_All_HealthCare_Settings_Eng2012.pdf.

Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). (2012a). Hand hygiene practices in health care settings. Government of Canada. http://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/430135/publication.html.

Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). (2012b). Routine practices and additional precautions for preventing the transmission of infection in health care settings. Government of Canada. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/nois-sinp/guide/ summary-sommaire/tihs-tims-eng.php

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2012). Routine practices and additional precautions assessment and educational tools: Protecting Canadians from illness [PDF]. File HP40-65-2012). Government of Canada. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2013/aspc-phac/HP40-65-2012-eng.pdf

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2016). Routine practices and additional precautions for preventing the transmission of infection in health care settings. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/routine-practices-precautions-health care-associated-infections/part-a.html [Date modified: 2017-09-05]

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2016). Appendix X: Technique for putting on and taking off personal protective equipment [images]. In Routine practices and additional precautions for preventing the transmission of infection in health care settings. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/routine-practices-precautions-health care-associated-infections/part-a.html [Date modified: 2017-09-05] [Images Reproduced with permission from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.]

Rees, J. (2017, October 2). Putting on sterile gloves VIMEO (2017 remake) [Video]. The University of Edinburgh. Media Hopper Create. https://media.ed.ac.uk/media/Putting+on+sterile+gloves+VIMEO+%282017+remake%29/1_wjlyrirj

Sorrentino, S., Remmert, L., & Wilks, M. (2019). Mosby’s Canadian textbook for the support worker (4th ed.). Elsevier Canada.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2009a). WHO guidelines for hand hygiene in health care: First global patient safety challenge. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241597906_eng.pdf?ua=1.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2009b, May 5). Figure 2. My five moments for hand hygiene [Image]. In Hand hygiene technical reference manual: to be used by health-care workers, trainers and observers of hand hygiene practices [PDF]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241598606

Precautions (including contact, droplet, and airborne precautions) that are necessary in addition to routine practices for certain pathogens or clinical presentations.