Chapter 11. Politics to 1860

11.10 Rebellions, 1837-38

Lower Canada

Papineau’s continued attempts to reconcile the interests of Canadiens with those of the empire were doomed to fail. Partly as a mark of the Parti Canadien’s frustration with the Château Clique, the organization changed its name to the Parti Patriote. This was something of a red rag to a bull. To be a “patriot” is to be loyal to the land of one’s birth first and foremost; the American revolutionaries had branded themselves “patriots” knowingly and so too did Papineau’s group. Dropping “Canadien” was also a sign of growing inclusiveness. The Parti became home to Irish and American immigrants, the Canadien peasantry and seigneurs, the liberal professionals, and those smaller anglophone merchants whose interests were not best served by the Clique. It was in this context, too, that Papineau introduced the Emancipation Act of 1834 that extended new rights to the Jewish population in the colony. This broadening of the movement’s reach was also felt at an ideological level.

Radical reformers within the Parti Patriote increasingly called for a more revolutionary approach. After all, Papineau and company had been fighting the same battle against the Clique for 20 or more years, with little to show for it. Despite having a majority in the assembly for years (and a landslide victory in 1834), they were unable to press their case. Papineau’s popularity was at an all-time high, but his defence of the French civil law, the seigneurial system, and the importance of the Church in the preservation of Canadien culture put him increasingly at odds with those who wished to see an overhaul of the entire social order. For those rivals within the Parti, the seigneurial system was an offensive holdover from a feudal system with which even much of Europe had dispensed, the clergy’s loyalties were to themselves and to Rome, and the Coutume de Paris was what undergirded the lot.

As a political figure, Papineau is elusive. He seems to have stood firmly against compromise of any kind, but by 1830 he was a fan of Jacksonian democracy. He was, as one biographer describes him, “violently anti-clerical” and a staunch critic of the Church’s powers and privileges, yet he defended the Church against what he saw as attacks aimed at reducing the cultural integrity of the Canadiens. He seems, as well, to have been tugged by contrary and momentary winds. If popularity lay in that direction, then off he went in search of it. While it is true that he had some authority as Speaker, Papineau and his fellow members of the assembly had little real power. They could afford to posture while the Château Clique attempted to govern.

In 1834 the Patriotes compiled the Ninety-Two Resolutions, an extensive shopping list of reforms that they put before the British government, along with a petition of nearly 90,000 signatures. Its tone was one of frustration and growing anger; it contained pledges of loyalty coupled with not-very-veiled threats of rebellion. The British had other matters before them, so they delayed and then brushed the petition off in March 1837 with Lord John Russell’s much more succinct Ten Resolutions. These countermeasures hardened the divisions in Lower Canada’s government by giving the executive more power over revenues and turning back any reforms that would increase the authority of the assembly.

The British response outraged the more radical elements in the Parti Patriote. While other reformers considered legal options, the radical part of the movement steeled itself for a confrontation with the governor and his forces. Meetings across the colony in 1837 whipped up support for the cause. At the largest of these, the Assembly of the Six Counties at Saint-Charles, some 4,000 to 6,000 people gathered to hear Papineau and the Parti’s other leaders. Although Papineau invoked Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man and called for an uprising, he had feet of clay. His indecisiveness may have reflected disappointment at the size of the rally at Saint-Charles (he had evidently hoped for more). Regardless of why he hesitated, it cost the movement some of its momentum. Rather than face the British forces in Montreal or Quebec, Papineau and his supporters fled into the countryside south of the St. Lawrence to avoid arrest.

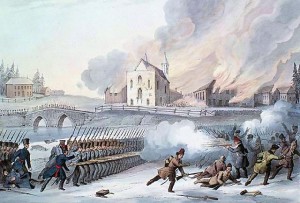

The response of the authorities was to suspend the constitution, declare martial law, and send British troops into the region in November 1837. Their first battle, at Saint-Denis, cost the British and the rebels (under the leadership of Dr. Wolfred Nelson) a dozen dead apiece. Subsequently, the rebel tactics became more desperate and the British response more bloody. Rebels at Saint-Charles were executed on the spot when they bluffed a surrender; buildings throughout the Richelieu Valley were burned to the ground. In December the battle turned north to Saint-Eustache where a force of roughly 200 rebels were defeated by a superior British force augmented by Loyalist volunteers. Nearly half the rebels died at Saint-Eustache, some of them burned alive in the church after it was set ablaze by the British troops.

Papineau and other leaders fled to the United States. Papineau in particular was fleet of foot, having run out of Saint-Denis within minutes of the first volleys being fired. His quick retreat was to cost him followers and credibility in exile. There was talk of launching a second rising from the United States, but this came to nothing apart from two minor skirmishes near the border. In November 1838, rebellion sparked again on the south shore, this time at Beauharnois. An imprudent rebel attack on the Iroquois community at Kahnawake (a.k.a. Sault du Saint-Louis and Caughnawaga) ended in the capture of 60 rebels who were then handed over to the British.

The underlying causes of the Lower Canadian Rebellion are complicated, which is why it is worth considering Papineau’s own perspectives. As a seigneur he had a vested interest in stability and continuity, as a notary he had an interest in the preservation of the French civil law, and as an educated francophone he acknowledged a debt of gratitude to the institutions of the Catholic church. At the same time, he viewed representative government as the best guarantee of cultural survival, he opposed the modernizing economy (mostly because it was in the hands of the British Canadians), he railed against clericalism, and he took steps to create a state-funded education system. Papineau broke down barriers that had stood against Jewish people in European societies for centuries and in this he was progressive; he also took steps to strip the vote from those female property owners in Lower Canada who were entitled to the franchise.

For the general population this was a time of economic uncertainty and fear of change. The arrival of large numbers of Irish immigrants threatened the demographic integrity of the Canadiens; the fact that the Irish inadvertently brought cholera with them did far worse. Some speculated that the Irish immigrants and cholera were both sent to Lower Canada to destroy Canadien society. Many of the rebels simply wanted a bigger slice of the pie. The fact that the Rebellion manifested elements of ethno-linguistic division along with sectarianism should not blind us to the fact that it consisted of many more factors as well.

Upper Canada

The rebellion in Upper Canada had similar roots to that in Lower Canada. It sprang out of dissatisfaction with the same constitution. It featured an oligarchy of wealth and privilege and a populist reform movement inspired by liberal principles. It was influenced by current events in Europe and the Americas that were pointing toward greater democracy and anti-imperialism. These underlying causes were furthered by specific grievances associated with the Family Compact’s economic strategy (which benefited Toronto but not necessarily the farming community) and division between the Church of England establishment and adherents of other denominations.

As in Lower Canada, the little power that the assembly might exert on the councils was limited by revenue sources over which the elected representatives had no control, which came from the sale of Crown lands, the revenues from which were at the disposal of the lieutenant-governor and the executive council. These monies were used in part to further the government’s canal-building strategy, a plan that did little to help inland farmers who would have preferred an aggressive road-building program. Many of these settlers were, moreover, adherents of Methodism and some of them were Presbyterians. These two denominations were the principal challengers to Family Compact efforts to see the Church of England become the established church. Armed with the Clergy Reserves as well as Crown lands, however, the Compact was in an excellent position to further the interests of the Anglican Church to the exclusion of the smaller denominations.

William Lyon Mackenzie was the leader of the cause in Upper Canada. His newspaper, the Colonial Advocate, was both a vent for radical-reformer positions and a target of Tory opponents. In 1826 a gang of Tories descended on Mackenzie’s offices in York, grabbed his printing presses and threw them into Lake Ontario. Intimidation was part of the Family Compact’s stock in trade, but events like this only served to legitimize the more radical positions offered by Mackenzie and his allies.

Not everyone in the reform movement shared Mackenzie’s position. The moderate wing continued to advocate a pro-monarchical position and was alienated by the radical side’s increasingly republican and pro-American language. Although the Reformers were able to control the assembly through most of the decade before the rebellion, they were viewed as ineffectual by Radicals (by then emerging as a separate camp entirely). The tension between the two factions grew as the 1830s witnessed insincere concessions by the lieutenant-governor, Sir Francis Bond Head (1793-1875). His strategy was to admit onto the executive two prominent Reformers — Robert Baldwin (1804-1858) and John Rolph (1793-1870) — and then to ignore their advice. Resignations followed, the assembly tightened its limited grip on the colony’s finances, and in 1836 Bond Head dissolved the assembly and called an election.

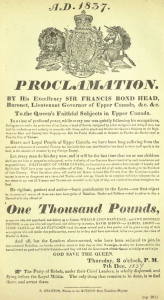

This was a turning point. Governors to this point had stood aloof in election campaigns, even if the Family Compact had not. But Bond Head waded in, describing the Reformer and Radical elements as American in their sentiments and loyalties. These were strong words from the Crown’s representative: he was accusing Mackenzie and company (the moderate Baldwin included) of treasonous ideals. Bond Head’s tactics were regarded, even in Britain, as excessive, but he succeeded in mobilizing the vote among recently arrived British immigrants who joined with the Loyalist establishment in defeating the Reform element.

Mackenzie, presumably tired of being called a republican, decided to publicly embrace the values of the United States and call for the overthrow of the regime. In early 1837 this was all still talk but then events in Lower Canada forced everyone’s hand. Bond Head sent his troops east to participate in the suppression of the rebellion there, leaving Upper Canada vulnerable. Rebels gathered in London and in York with an eye to striking while the opportunity presented itself.

The events that followed were profoundly anticlimactic. Mackenzie’s group mustered at Montgomery’s Tavern, about seven kilometres north of Toronto’s waterfront on Yonge Street. Over the next two days they would engage Loyalist volunteers twice and would collapse both times. Along with John A. Macdonald, the militia units included the retired fur trader and explorer Simon Fraser, heading up a regiment of the Stormont Militia. The troops captured several rebels and torched the inn. Mackenzie fled to the United States, as did most of the rebel party in London.

There was one last battle in the Upper Canadian Rebellion. Near Prescott, roughly midway between Montreal and Kingston and across the river from Ogdensburg, a force of exiled rebels and American sympathizers (together known as Hunter Patriots or the Hunter Lodges) attempted an assault on Fort Wellington. Although they held their position for four days, holed up in a stone windmill, the attack failed.

In the aftermath of the Upper Canadian Rebellion, the Family Compact had an opportunity to bare its teeth. Nine of the Toronto rebels were hanged along with 11 from the Battle of the Windmill. Prison sentences awaited over 1,000 of the rebels and exile (or “transportation”) to Australia awaited 100 more.

The Atlantic Colonies

Curiously, the Maritime colonies received much of what reformers in the Canadas demanded without mounting so much as a protest march. In 1837 Britain conceded to the colonial assemblies the right to control money bills with the proviso that the civil list — the very heart of the patronage machinery — remain in the hands of the executive. New Brunswick took up the offer first and Nova Scotia followed soon after; Prince Edward Island had it imposed on them in 1841. Settlements of this kind served to legitimize rather than marginalize the Reformers in Maritime society. The case may be made that Nova Scotia and New Brunswick achieved responsible government in large measure because of what happened in the Canadas. But change was already taking place in the Maritime assemblies before the rebellions; they were marching to a different beat. And for people like Joseph Howe, that meant greater credibility and a wider audience for his demands for an assembly that governed the executive branch.

Howe presents an interesting case because he changed his views on government. Until the 1830s he regarded it as a consensus-based process in which goodwill and commonsense would prevail. In this he was not greatly different from many other Reformers. But this was an age of ideologies and increasingly it was becoming clear that Old Tory privilege and hierarchy was at odds with the emergent liberal, middle-class views of individual opportunity and equality. In the pages of the Novascotian he lambasted assembly members he thought weak, and civic officials and a judiciary that he regarded as corrupt and venal. In 1835 he was charged with libel and celebrated his victory in the courtroom with the proclamation that “the press of Nova Scotia is free.” And indeed it was: free to criticize the regime without fear of reprisals.

Thereafter Howe ramped up his attacks on Nova Scotia’s oligarchy and sought elected office himself. In the wake of the Durham Report he wrote to the Colonial Office, “the Colonial Governors must be commanded to govern by the aid of those who … are supported by a majority of the representative branch.”[1] Throughout these years, however, Howe was distrustful of party politics, which he believed tended toward narrow factions. Nonetheless Howe gets credit for so significantly changing the political culture of Nova Scotia that Reform majorities were elected in 1836 and 1840. This last victory prompted what may have been the only act of violence in Nova Scotia’s march to responsible government. According to Howe’s biographer, “His success so antagonized the official faction that [Howe] was forced to fight a duel with John Halliburton, son of the chief justice, on 14 March 1840; Halliburton missed and Howe fired his pistol into the air.”[2]

Howe was not the first to do so, but he articulated as well as any other British North American leader in his generation the shift to an ideologically informed position and plan for the future. While ideology did exist in the pre-1830 period, afterwards it became clearer in the colonies that visions for the future were at odds.

Key Points

- The 1830s saw the Parti Canadien rebrand itself as the Parti Patriote and launch an increasingly broad-based campaign against the oligarchy under the leadership of Louis-Joseph Papineau.

- Refusal on the part of the oligarchies to make concessions to assembly demands for more authority pushed reform elements toward radical republicanism.

- The rebellions of 1837 and 1838 failed to either attract widespread support or mount effective battle plans. They failed badly and were violently suppressed.

- Reform arrived in the Maritimes with only one shot being fired.

Attributions

Figure 11.6

Lower (Bas) Canada City Bank One Penny (Deux Sous) Bank Token 1837 by Centpacrr is used under a CC BY SA 3.0 license.

Figure 11.7

Assemblée des six-comtés painting by Jeangagnon is in the public domain.

Figure 11.8

Battle of Saint-Eustache by Scorpius59 is in the public domain.

Figure 11.9

1837 Proclamation by YUL89YYZ is in the public domain.

- “Joseph Howe’s Letters,” ed. J.M. Bliss, Canadian History in Documents, 1763-1996 (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1996), 65-69. ↵

- J. Murray Beck, “HOWE, JOSEPH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 10 (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003). Accessed January 15, 2015, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/howe_joseph_10E.html ↵