Chapter 11. Politics to 1860

11.14 The 1850s

Tories on an arson rampage in Montreal, annexationists popping up in what had hitherto been Tory circles, and responsible government breaking out in three — soon all five — British North America colonies in the east. It was on this note that the 1850s opened. In the history of formal politics in Canada, no decade has such a record of discord, frustration, and dysfunction. It was also one that witnessed innovation, invention, and growing political sophistication.

The Act of Union was the Province of Canada’s constitution for only 26 years, only half as long as the Constitutional Act of 1791. Many historians have viewed this as a period of stalemates and failures, one that led via a chain of crises to Confederation. This perspective held sway down to the 1980s, by which time historians were observing that the constitution also presented opportunities and in some cases forced opportunities upon politicians.

Three issues stand out in the political history of the Canadas in the 1850s. First is the emergence of political parties and coalitions. Second is the stymied attempts at the cultural assimilation of French Canada, and third is the rise of railway politics.

Party Lines

Several issues animated political discourse in this decade, but annexationism wasn’t really one of them. It peaked in 1849-50 and thereafter remained a fringe movement, even if that fringe did include some of the most powerful people in Montreal and Toronto. Part of the anger in the late 1840s stemmed from disappointing and frightening economic times, which many associated with Britain’s move to free trade. As the economy improved, so did Tory support for the new political situation. Besides, fractures in the Reform movement were starting to show.

Radicals from Canada West were once again led by William Lyon Mackenzie. Like Louis-Joseph Papineau, Mackenzie had returned from exile and leapt back into politics. He still commanded a following but it was quickly commandeered by others on the radical wing of Reform, most notably by George Brown. Their position was one of continued opposition to the Family Compact (now more-or-less repackaged as the Tory Party) and to the Montreal merchant Tories as well.

Radicals found it hard to stomach the moderate reformers who found their economic plans (and personal interests) increasingly aligned with the old enemies. Brown made clear what he thought the Reformers lacked when he called for a party of “men who are Clear Grit,” meaning morally upstanding and firm. This was a strangely anti-materialistic movement that reflected rural suspicion of the cities and towns, Anglicanism, Catholicism, big business, and Montreal as a whole. The Grits, moreover, remained a bastion of anti-French feeling, a position that would be expressed most clearly in their position on the composition of the Assembly.

One of the challenges of studying this decade of colonial politics is the speed with which political leopards changed their spots. Take John A. Macdonald, for example. In 1849 the 34-year old lawyer from Kingston and Conservative member of the legislature supported the call for “no French domination;” six years later he was forging a coalition with George-Etienne Cartier (1814-1873) and his moderate-reform party, the Parti Bleu. This is the same Macdonald who, as we know, carried a rifle against the rebels in Upper Canada, now going into political partnership with a man who had fought his way out of the siege of Saint-Denis, laid low for a year, and fled into exile with Durham’s death sentence hanging over his head. More than that, Macdonald was able to co-opt much of the Reform Party from Canada West and bring them into his party. By 1851, even the bulk of Papineau’s adherents had become more comfortable with the establishment and they built their own coalition with (formerly despised) Reformers. The saying that politics makes strange bedfellows certainly applies to Canada in this decade.[1]

By the end of the decade these swirling fractions had coalesced around two party banners: Liberals (made up mostly of Grits and disaffected Reformers from Canada West, and the Parti rouge from Canada East) and Conservatives (the Macdonald-Cartier group). The order that arose from what was essentially a chaotic decade proved durable: these two parties have dominated Canadian politics with few rivals to the present day, and no other party has formed government at the national level.

It is remarkable how quickly politicians in the two Canadas came to an understanding on how they might best proceed. United though the two colonies were, they retained sufficient internal differences and distinctions that one could identify three parties in each of Canada West and Canada East. No single party could hope to achieve a clear majority outside of a coalition. Even two-way partnerships were not enough: a healthy plurality was the best any party alliance could hope for and what a stable government required. The ability to broker deals was critical to a ministry staying in office, and few could pull it off. Macdonald’s palpable talent in this regard is what most suited him for success in Canadian politics across more than a generation.

Assimilation

Nothing underlines the loss of absolute certainties in Canadian politics like the issue of assimilation. In 1838 Durham laid down a goal and a game plan for the assimilation of French Canada into what he viewed as the more aggressive, forward-looking, and democratic English Canada. The assembly itself was to be the most important instrument of this assimilation process. As we’ve seen, the ability of the Canadien members to close ranks against assimilation was greater than the ability of Canadian members to mount a united front against French Catholicism. Partly this was a numbers game: when Union began in 1841, the two halves of the Province of Canada had the same number of seats, which meant, despite larger numbers of anglophone-dominated ridings, it was a close thing.

At the time, anglophone politicians were deaf to complaints from Canada East that its population was larger and so deserved more representation, particularly in the French-speaking regions. The 1851 census — the first coordinated census of the united colony — revealed that Canada West’s numbers were significantly higher and, as we’ve seen, the Grits responded with a call for representation by population. More seats in anglophone Canada West would enable the assembly to do what Durham designed it to do: drown out the Canadiens, strip them of their current political advantage, and impose the measures necessary for assimilation. It would also improve the possibility of Radical control of the government because it would inevitably create additional seats in Reform- and Grit-friendly areas, not in Tory hotbeds. This is, presumably, one reason why the Anglo-Tory elements were not enthusiastic supporters of representation by population. And without the support of members of the assembly from Canada East — who were not prepared to endorse their own political disaster — representation by population was a non-starter and the Grits were relegated to the governmental sidelines.

The political heirs of the Parti Patriote — the Parti rouge — did, however, share Grit concerns regarding the emergence of railway politics, a phenomenon involving conservatives and reformers alike. The Rouges remained fearful of anything that threatened Canadien culture and in this the Grits and Rouges were obviously at odds. But they shared some other interests and goals. The Rouges were supporters of republicanism (which echoed Grit sentiments), and they were anti-clerical/secularist (which, when aimed at the Catholic Church, appealed to Orange feeling among the Grits). Mostly they shared a lack of confidence in the moderate Reformers led by Baldwin. Consequently, alliances that spoke to common issues were forged across the linguistic divide between these two parties while, for the moment, guaranteeing that truly offensive legislation would be kept off the table.

This was the furthest thing from what was intended in the Act of Union. The proposition that anglophones would find more in common with francophones based on political goals and values was essentially unthinkable. These developments, however, raise the question again: assimilation into what?[2] If the goal of Durham and Britain was to extinguish French language, habitant culture, and Catholicism in Canada, then clearly they had failed. And one might reasonably wonder whether the Anglo-Canadians and their British governors ever had the right tools to accomplish that task. But if we look again at Durham’s critique of Canadien feudalism as the principal obstacle to economic and political progress in the colony, how then does the Act of Union measure up? What becomes of Canadien quasi-feudalism?

In 1854 the assembly passed An Act for the Abolition of Feudal Rights and Duties in Lower Canada. This occurred with the support of assembly members who had rallied at the Six Counties in 1837 and who saw the institutions of the Canadien countryside as critical in the preservation of culture. Through the 1850s francophones in the assembly were key to making coalitions succeed. As we shall see, their engagement in industrial enterprises was second to none. In these ways the Canadiens were, indeed, assimilated by 1860, not in terms of language or religion (although the anti-clericalism of the Rouges/Liberals was never understated), but in terms of a reorientation away from feudal values to those of a modern, commercial, industrial, and democratic polity.[3]

Exercise: Documents

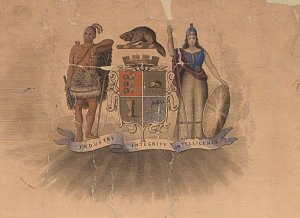

William Lyon Mackenzie’s Toronto

Well into the late 19th century, city maps were extravagant ways of charting progress, advertising prosperity, and both capturing and inspiring a sense of place. This 1842 map of Toronto drawn by James Cane (see Figure 11.E1) does a number of things well. It shows the city’s advance away from the waterfront and to the west, the retreating forest to the north, the few large estates that will be swallowed up, and the future location of the University of Toronto. The coat of arms at the top (see Figure 11.E2), which Mackenzie had a hand in developing, invites some reflection. What does it convey?

The profile of the city (at the bottom of the map in Figure 11.E1) gives you a sense of the skyline. Toronto in 1842 may have been the largest city in Upper Canada (a.k.a. Canada West) but it was really just a village. The offices of Mackenzie’s Colonial Advocate were located a block in from Front Street on Frederick Street. It was from there that Tory vandals dragged his printing press and threw it into the lake. In later years, the former mayor of Toronto was provided with a home for his retirement at 82 Bond Street, between Yonge and Church, just north from Shutter Street — on land which in 1842 was only just surveyed (and which is reputed, by the Toronto tourism industry, to be intensely haunted). Otherwise, what does this map reveal about the people and place of Toronto at mid-century?

Railways

These newly minted perspectives found their clearest expression in railways. The 1850s, as seen in Chapter 9, was the decade in which railway-mania first exploded across British North America. Railroads were about economic development and diversification, a make-work project, a brilliant way to win votes in the communities through which they might pass, and a stick with which to beat opponents. The rivalries between Montreal and Quebec, Toronto and Kingston, meant that the Grand Trunk Railway went around Kingston and never reached Quebec. That was neither an accident nor oversight. In an age where the notion of conflict of interests was not fully tested, leaders like Cartier and Alexander Galt (1817-1893) were fully invested in the colonial railway projects. The public showed more concern when evidence arose of payoffs to Canadian politicians by railway promoters, a trend that would continue after Confederation.

The railways and the possibility of obtaining additional railway charters would dominate much of public discourse in these years. While they were, in a sense, a licence to print money, they were also enormous sinkholes of debt. They could make or break a community and, it was feared, even a whole colony. Their costs and possibilities would continue to inform political life in British North America for the rest of the century.

Election Day

Democracy in these years was a limited thing. Property ownership was the price of entry and, outside of Lower Canada, maleness a condition of membership. The franchise extended only to permanent residents in a community so transient workers and people who rented or were tenant farmers or owned only small amounts of land were excluded from the electorate. With the exception of Lower Canada, where women could own property, there was no female suffrage. Broadly speaking, across British North America, this kind of democracy was more akin to shareholders voting on a company directorate.

The conduct of public voting revealed further limitations in British North America’s democratic culture, wherein the small number of electors were always and vastly outnumbered by other adults who were not eligible to vote. Consider this scenario. In 1863 the coal mining town of Nanaimo had a population of about 500, making it the second largest city in the colony of Vancouver Island; the local electorate consisted of seven men and none of them were coal miners. On election day that year only five of the electors voted (in a public meeting with a show of hands) and the outcome was a near thing: a 3-2 win for Charles Bayley. The successful candidate reported subsequently that, within minutes, “the usual festivities commenced and being duly cheered by the people [I] was carried to my residence.”[4] The “people” — the miners and their neighbours and families — were present and involved, but not as voters. It is fair to ask in this context whether this kind of politics mattered much to them, or whether other struggles for power and/or survival took precedence.

Engagement in political events was limited in other ways as well. When we look at the rebellions, it is their failure as popular uprisings that leaps out. Papineau rallied 4,000 or more at the Six Counties but there were never that many involved in the sieges at Saint-Denis or Saint-Eustache. The countryside did not rise up to support the rebels. Nor did Upper Canada’s independent farmers turn out in numbers to support Mackenzie. Contrast this with the hundreds who participated in Orange Riots aimed against Irish Catholic immigrants in New Brunswick in the late 1840s. Certainly the rebels of 1837-38 were fighting the established authority while the Orange Lodges in Saint John were not, but the Tory arsonists of Montreal in 1849 were heaving rocks at the governor himself. The extent to which British North Americans were enthusiastic about orthodox and constitutional politics remains in question.

Perhaps the stakes were too low. Whether as voters or as members of a legislative assembly or an executive council, there was only so much British North American political participants could do. Responsibility for formal education and health care — the critical elements of today’s provincial administrations — was small because publicly funded schools and hospitals were few and far between (although that was just starting to change in this period). Foreign policy and defence were both very much in the hands of Britain. The colonial administrations were responsible for two things that mattered a great deal to colonists: the nature of land ownership and taxation. And the colonial regimes were not very good at either of these. Complaints ran throughout this period regarding the inefficiencies of land registration — a key element of any agrarian economy and a source of conflict in the mining sector. Taxes were highly divisive and the greatest source of recurrent political tensions. In Canada, a tax on trade was anathema to merchants while a tax on land was repugnant to farmers; and if the latter were taxed to pay for canals that benefited the former, the political heat was instantly dialled up. This was briefly a lightning rod for political energies but it became dulled by changes in the economy.

In other words, democracy was something directly experienced by a minority, and it produced governments with limited powers whose ability to do what mattered to colonists was limited. What mattered more were jobs and investment, something in which governments participated sparingly. Infrastructure projects were the clearest manifestation of public spending but these were sporadic and Britain could be turned to for support (sometimes with success). The kind of political rivalries that existed in the 1840s to 1860s led to the “spoils system” becoming a trademark of Canadian (though not Maritime) politics. Holding office and being part of an administration meant securing contracts for construction in one’s constituency and appointing supporters to the few public offices available. This would become a more powerful feature of Canadian political culture after Confederation.

Key Points

- The emergence of political parties complicated the possibility of an English-French dichotomy in the assembly.

- Ideological commonalities came to play a greater role, as did pragmatism about potential alliances.

- Despite its significant shortcomings, the Act of Union forced Canada’s politicians to seek out partnerships across old barriers.

- The goals of linguistic and spiritual assimilation were never met, but a modernization of Canadien economic and political life did occur within less than a decade.

- As Aboriginal peoples were pushed off of highly desirable farmland, confrontations shifted to the mineral and timber resource sectors.

-

The declining living and economic conditions of Aboriginal peoples that arose from colonialism became the newcomer societies’ rationale for limiting investment in the welfare of First Nations.

Attributions

Figure 11.11

William Lyon Mackenzie by Mortadelo2005 is in the public domain.

Figure 11.12

John A Macdonald in 1858 by Jbarta is in the public domain.

Figure 11.E1

Toronto Cane map by Schrauwers is in the public domain.

Figure 11.E2

Revised from Toronto Cane map by Schrauwers is in the public domain. This version is released under a CC-BY 4.0 International license.

Figure 11.E2 long description: An aboriginal man and a woman holding a shield stand on each side of the coat of arms. A beaver sits above it. Underneath them reads, “Industry, integrity, intelligence.” [Return to Figure 11.E2]

- Ged Martin, John A. Macdonald: Canada’s First Prime Minister (Toronto: Dundurn, 2013), 58. ↵

- Katherine Fierlbeck, Political Thought in Canada: An Intellectual History (Peterborough: Broadview, 2006), 142-144. ↵

- This is the position argued by Janet Ajzenstat, The Political Thought of Lord Durham (Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1988), 4-12. ↵

- British Columbia Archives, Charles Alfred Bayley, TS, Reminiscences: "Early Life on Vancouver Island" [1878?], 22. ↵