Chapter 14. The 1860s: Confederation and Its Discontents

14.3 Confederation as a Cure-All

The late 19th century saw the rise of the patent medicine industry in North America. Backed by anecdote and perhaps some folk-remedy pedigree, the patent medicines promised to cure anything and everything. At best they might have a benign placebo effect. Confederation was a bit like these cure-all medicines. It promised to address everything that was wrong with British North America, but closer examination suggests that it was neither necessary nor effective.

Apart from the political stalemates in Canada, there were three issues that drove the discussion forward — issues that made Confederation seem both imperative and the best solution. First was the concern that the United States threatened the welfare of the colonies. This was mostly a theoretical danger; the Fenian element made it more real. Second was the argument that some effort was needed to replace the recent loss of markets in Britain and, in 1866, the end of freer trade with the United States; might a single colonial marketplace compensate for some of those losses? And third was the issue of infrastructure and, specifically, an intercolonial railway.

America: Threat or Menace?

British North Americans had conflicting sentiments about the United States. Their rivalries had historically been with New England and New York, and a little with Virginia. There were plenty of New Brunswickers alive who remembered the Aroostook War (1838-39) and the loss of a substantial western flank to the state of Maine in the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842. They might find a market for their timber products in the United States, but their feelings toward New England were generally cool.

Further, despite its own opposition to slavery, Britain supported the southern Confederate states during the Civil War. This left British North America exposed to the Northern/Union States’ ire. British North Americans might not have agreed with Britain’s actions in this instance, but they recognized that the ability of the empire to set international policy remained unchallenged. There was, for British North America, no diplomatic channels it could pursue directly to defuse the situation.

The American bogeyman was a more real source of fear for British North America in the 1860s than it had been since the 1837-38 rebellions. It posed a threat in three ways: the future of reciprocity, the implications of the Civil War, and the Fenian threat.

Reciprocity

The Canadian-American Reciprocity Treaty of 1854 had offset the worst aspects of the loss of preferential treatment in British markets and inevitably drew the British North American economy closer to its neighbour. The treaty was held to be a great success, especially after 1861 when Civil War broke out and demand for goods from south of the border grew.

The northern states, however, viewed British North America as a stalking horse for British manufactures. That is, they feared that less expensive and more competitive British products were being brought into the United States via British North American ports. If this was the case, it would sap the vitality of American industries. (American exporters had pursued an identical strategy earlier in the century, smuggling their grain into Canada and then passing it off as Canadian products in the British market.) Canada managed to put in place a tariff to protect its own manufacturing base and this, too, annoyed the Americans.

Civil War

The northern states were emerging as industrialized competitors to Britain in the North Atlantic at the very moment that British cotton mills were relying more and more on the products of southern plantations. Morally, British support was with the Union (the northern states) and against the Confederacy (the South) on the issue of slavery; economically, it supported the Confederacy. Both Britain and British North America were officially neutral, but both jurisdictions were slippery on this point.

The British very nearly leapt into the fray at the very beginning of the Civil War. Two envoys from the South were heading across the Atlantic on the British steamship the Trent in November 1861, bound for diplomatic talks in London. A Northern naval vessel stopped the steamer and seized the envoys, precipitating a crisis that could have plunged British North America into war. Subsequently, the Confederate Navy ship, the CSS Alabama, which had been built in the early days of the war in a shipyard near Liverpool in England, terrorized Northern shipping and drew outrage from Union politicians. Britain, they argued, had taken sides and the prospect of a transatlantic war inched closer. Some Northerners called for the capture of British North America in compensation. Tensions rose again when, in 1864, a small band of pro-Confederates in Canada East ran a raid across the Vermont border on the town of St. Alban’s. They cleaned out the local bank, escaping with what was then the enormous sum of $200,000. They were arrested in Canada, but a Montreal judge freed them on a technicality. Again, the Union states were outraged.

Faced with the threat of an American attack on British North America, the British dispatched some 14,000 troops, the largest contingent since the War of 1812. While this calmed colonial nerves to some extent, it also served to highlight their vulnerabilities. Deploying the troops along the American frontier was difficult and the troops struggled to get from Halifax to Canada. Observers and authorities alike realized that a land route, ideally a railroad, was badly needed. The North rattled sabres but did not attack, at least not militarily. Instead, it cancelled the Reciprocity Treaty.

The U.S. Civil War had benefited British North America economically by increasing demand for raw materials, and the colonies’ balance of payments improved as a consequence. So although the Civil War might have given British North Americans cause for concern when it came to diplomatic crises, it was decidedly good for business. In the United States, as everywhere else, the lobby in favour of freer trade was countered by a protectionist interest. At the end of the Civil War, in 1866, the protectionists joined with those Northerners still irate about the Alabama affair and the St. Alban’s raid to force an end to reciprocity. This happened very late in the development of constitutional proposals in British North America, so it cannot be said to have catalyzed the process. Nevertheless, it served to push public opinion in British North America further toward the view that an inter-colonial economic alliance was in order.

The Fenians

The final issue coming out of the United States that influenced the talks on Confederation came from the Irish-American community. There was some talk in the United States after the Civil War, in the spring and summer of 1865, of turning the troops northward and capturing British North America, and one group of war-hardened veterans took up the challenge. Irish-British relations on the other side of the Atlantic were poor, and Irish-American citizens viewed British North America as the soft underbelly of the empire. Known as Fenians, they formed their own regiments and launched their attack in April 1866.

The first invasion came at Campobello Island on the seaward border between New Brunswick and Maine, but it was chased off easily by a Royal Navy response out of Halifax. A more serious threat followed on the Niagara Peninsula in June 1866, marked by the Battles of Ridgeway and Fort Erie. These, too, were repulsed, although the Canadian militia regiments embarrassed themselves against the much better disciplined and tough Irish. A final foray saw Pigeon Hill in Canada East, less than 40 kilometres from St. Alban’s on the Vermont border, captured briefly.

In each instance the American government was quick to denounce the Fenians, whose stated goal was to hold British North America hostage in exchange for Ireland’s liberation from Britain. Nevertheless, British North Americans quite rightly recognized what the Fenians had demonstrated: the American border was porous and that whatever a well-drilled gang of raiders might accomplish would be as nothing compared to a full-blown American invasion.

The Fenian and American threat genuinely troubled British North Americans. The American frontier was an issue regardless of the Fenians and heightened vulnerability during the Civil War was only temporarily offset by increased exports from British North America to the Union and Confederate States. When the first meetings to discuss a union of British North America colonies took place in 1864, no one could know for sure how long the war to the south would persist. At some point it would have to end and demand for colonial products would shrink, unless they were sustained by reciprocity. No one in 1864, too, could have anticipated the Fenian element two years later. What was clear from the outset is that uniting the colonies seemed logical in light of the possibility of an attack from the south. The obvious criticism of that argument is that there were almost as many people enlisted in the Union and Confederate armies in 1866 as there were in the whole of British North America. Defending the Canadian frontier against further Fenian attacks, let alone United States Army depredations would require much more than a few militia movements to turn the tide.

The question of an American threat was a real issue; the proposal of a federal union, however, was not a real answer. That leaves the trade relationship to consider.

The Balance of Trade

The most palpable, fundamental, and pressing of the problems facing all the colonies was the loss of protected markets abroad. The introduction by Britain of free trade and the threatened (and eventual) loss of reciprocal access to American markets hurt all of the colonies and the Atlantic colonies especially. Presumably a united single colony would facilitate expanded intercolonial trade. Freer access to Maritime markets would benefit Canada East (Quebec) in particular; a “national” marketplace that included Ontario and Montreal might, too, galvanize the Atlantic colonies’ economies. Confederation might thus prove to be an economic engine that could substitute for declining markets elsewhere.

This proposition suffered from two principal weaknesses. First, there was the lack of complementarity. Trade, almost by definition, implies that the participants come to the table with goods that the other parties do not have, which was not the case in British North America. Quebec, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick all had fisheries, so they were hardly going to trade the same fish back and forth. If New Brunswick was to benefit from access to Canadian markets, it would be in its area of strength: forest products. But the Canadas had their own forest industry and they were, moreover, inclined to protect it. There did exist some areas of specialization, but what is most striking is the lack of differentiation between the colonial economies. And while it is true that Canada produced more manufactured goods than the Maritimes, the addition of the Atlantic colonies could hardly replace the loss of either American or British markets. There were only about 800,000 people in the three Maritime colonies together, a far cry from the millions to whom Upper Canadian grain had once been sold in the United States.

Having to buy from Ontario and Quebec, moreover, might prove to be a liability to the Maritime economies, as Canada was industrializing much faster than the Atlantic colonies. Reciprocity provided a break in tariffs, but the dread remained in Canada that her infant industries would be strangled in their cradle by foreign competition. Maritime farmers and manufacturers who were competing against New England industries would want, naturally, to purchase lower-priced American produce (that is, ploughs or engines) to keep their costs down. Caught behind a Canadian tariff wall they would have to buy higher-priced Canadian products, almost all of which would come from Ontario or Quebec.

The Canadian tendency toward protectionism was countered by the Maritimes’ preference for anything that stimulated trade and traffic. Nova Scotia, for one, wanted freer trade because the colony operated in a larger, ocean-based marketplace. And in Prince Edward Island, as one study has pointed out, colonial revenue came overwhelmingly (75%) from customs duties (compared to Canada, where customs duties contributed only a third of revenues). Confederation was not likely to resolve this problem of shrinking international markets and a stagnant balance of trade.[1]

The Intercolonial Railway

We have already seen how the 1850s spawned a generation of railroad enthusiasts. The speed, size, and power of the new locomotive technology caught the imagination of thousands. Politicians in jurisdictions worldwide made hasty promises to their constituents that railway construction was just a vote away. New Brunswick Premier Charles Tilley was one of these. From the 1850s on he had been fighting for an intercolonial railroad that would connect Canada with an ice-free port in Saint John. In 1861 it became clear that troop movements would be vastly slower than on the other side of the border, should the Americans ever decide to chance an attack on the colonies. With expanded trade and improved security in mind, Tilley had lobbied in London for loan guarantees and had pleaded with banks; the necessary commitment from Canada, however, proved elusive. New Brunswick’s support for Confederation, he believed, could be made conditional on a firm buy-in from the Canadians. And if London really wanted British North America to make its own way in the world, the Crown could guarantee the loans needed.

The appeal of the intercolonial railway was undeniable. An early problem was, however, that there were at least two imagined versions. The first sped along the eastern border of New Brunswick, linking Quebec City and Saint John; the other looped eastward, closer to the coastline near the Mirimachi before heading south. The first was fast and, as it would be significantly shorter, comparatively cheap, but entirely exposed to attack. The second would be more expensive to build and longer (therefore slower in getting goods to market) but far enough inland that it could not be easily cut by American invaders. In short, the alternatives were cheap but vulnerable versus safe but expensive; neither was optimal.

So the railroad might not be a solution at all, but if it was going to be built anyway, Confederation was seen as the answer to the problem of funding, and the colonies had been within a hair of getting that funding in 1862. Guarantees were in hand and the Maritimes were ready to get started. The Canadians, however, backed out for political reasons. In other words, it wasn’t federal union that was needed to secure a railway, it was a firm agreement between partner colonies.

The conventional causal explanations of Confederation, very clearly, can be criticized. Improved defence, expanded markets, and the intercolonial railway were either beyond the ability of colonial union to deliver or could be achieved through other means. This reveals two things: The first is that the psychological importance of issues like defence exercised such a powerful force on public opinion that elites and voters alike overlooked the fact that the colonies could never overpower the United States. The same was true when considering the trade arrangements between the colonies; all parties likely hoped for the best and for improved economic conditions. At least, they had to believe they would not be worse off for having come together (although many anti-Confederationists argued just that point).

The second is that it pays to look at political decisions from different angles. The intercolonial railway might prove to be a white elephant, but its construction would entail much job creation and vast orders for steel. Defending the realm might prove a fool’s errand, but in the interim those garrisons would need feeding. However the leaders of British North America in 1864-67 imagined these problems and their solutions, whether reasonable or not, a host of politicians chose to pursue unification. Their first stop was Charlottetown in the autumn of 1866.

Key Points

- Three issues dominate the march to Confederation: the threat posed by the United States; finding a response to British free trade and the loss of reciprocity with the Americans; and the question of railways.

- The American Civil War and the Fenian invasions represented a psychological and material cause for concern in British North American politics.

- Free trade created both economic and political challenges for British North America.

- The intercolonial railway must be understood as the material manifestation of Confederation.

Attributions

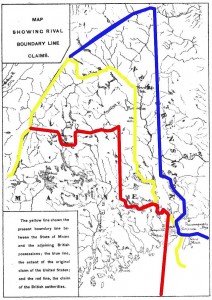

Figure 14.5

MaineBoundaryDispute by Magicpiano is in the public domain.

Figure 14.6

Marco Polo by State Library of Queensland is used under a CC-BY-SA 2.5 license.

- Canada, Parliamentary Debates on the Subject of the Confederation of the British North American Provinces, 3rd Session, 8th Provincial Parliament of Canada (Ottawa: 1865): 342-3. ↵