Chapter 14. The 1860s: Confederation and Its Discontents

14.1 Introduction

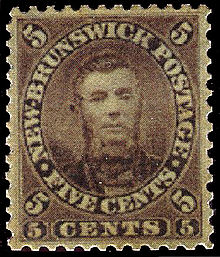

In the 1850s and 1860s, cracks began to appear in the relationship between British North America and Britain. The 1859 New Brunswick stamp shown in Figure 14.1 makes two revealing breaks with imperial norms. First, its value is shown in cents, not British pence. Currency issues had plagued colonies in the West Indies and the rest of the British Empire for centuries, and there was no unity on this subject even among the colonies of British North America at mid-century. Second, the new postmaster for New Brunswick, Charles Connell, unsure of the shifting protocols, scandalously chose to put his own face on the stamp, rather than Queen Victoria’s. This was too much change far too soon, and Connell demonstrated remorse by buying up as many of the stamps as could be found and burning them on his front lawn.

Connell wasn’t the only one receiving mixed signals from Britain. The Colonial Office was increasingly demanding loyalty while services and benefits were being systematically withdrawn. Free trade and greater political autonomy obliged the colonial leadership in British North America to think more strategically about their future, including alternative political structures. But it would be a mistake to think that Confederation was the only outcome being considered, or that it was an inevitability. It was neither.

Several options presented themselves, the foremost being joining the United States. Together or separately, by the 1860s all of the colonies at some point considered annexation. Barely a decade had passed since the campaign for annexation had been at the height of popular discourse and held its widest appeal. Since then, the idea had lost much of its support, but there were still many enthusiasts for the idea. As we shall see, it was an option considered very seriously in the Red River Colony as the prospect of union with the Americans held the allure of better access to large and expanding markets. Even in Canada it was easy to see that union with, say, Prince Edward Island would never have the same economic impact as closer trade ties with the United States.

Another option was the status quo, which was the choice Newfoundland made for another 80 years. Carrying on without change in the Province of Canada would mean thrashing through some pernicious constitutional and operational difficulties, but couldn’t be ruled out. Those who supported this option looked to other jurisdictions — Italy comes to mind — that had survived and even thrived under governments made of fragile coalitions. Many of Confederation’s critics, Nova Scotia’s Joseph Howe for one, argued for this: “Now my proposition is very simple,” he said, “It is to let well enough alone.”[1]

Smaller unions were also considered. Maritime union was, briefly, a very real prospect, one that would have created a single colony out of three (four if Newfoundland joined in). Union was thrust on the two West Coast colonies in 1866: Vancouver Island became just another region in the colony of British Columbia, although it did win the capital away from the mainland. And in Canada proper, George Brown made it clear that the minimal change he would accept in exchange for his cooperation was a federal reorganization of Canada West and East. This would have necessitated the dissolution of the Act of Union only to create a voluntary union of equal partners with separate legislatures and a central administration. From eight separate colonies in 1865, four could have coalesced by 1867.

One must ask, too, if any of these solutions really addressed the question at hand. If the issue was replacing British trade and/or American reciprocity, then the colonies could have pursued a customs union (sometimes called by the German term, zollverein). If it was the business of getting a loan to build a railway, then better finances, not a constitutional change, would do the job. If the issue was the defence of British North America against the Americans, who housed a huge post-Civil War army, then the only conceivable answer was closer ties with Britain, not semi-independence.

In short, under these alternative scenarios, the 1870s could have opened with a federal Canada stretching from Lake Huron to the Gaspé, a reunited Acadia on the East Coast, and Red River (or perhaps Assiniboia) added on to the U.S. Midwest. British Columbia could well have vanished into what, in the 20th century, was promoted as Cascadia, a region stretching from California to Alaska. Or the colonies might have clung more tightly to the hem of Mother Britain’s skirt in an imperial federation and eschewed any kind of union at all.

Every one of these options was serious considered in the 1860s. The solution at which political leaders arrived was influenced mainly by external factors and specific ambitions. This chapter surveys those elements and the implications of the new constitutional configuration. It also explores the emerging relationship between Canada and the West, without which the proposal for a union of colonies might not have proceeded. (Turning it on its head, if there had been no colonial union, there would likely have been no Canadian annexation of the West either.) Finally, this chapter pays some attention to the changes underway in the economy among Aboriginal peoples and culturally in British North America as the 1860s drew to a close. It is important to realize that while this decade is usually dominated in Canadian history by the achievement of a new constitutional arrangement, it was also a springboard for vast, sweeping changes in social and economic life. By the 1880s, Canada as a whole was experiencing a full-blown industrial revolution while Aboriginal peoples on the Plains faced famine and landlessness. These and other critical moments in Canada’s history have their roots in the 1860s.

Learning Objectives

- Describe the alternatives available to British North America’s politicians on the eve of Confederation.

- Critically assess the internal and external forces leading to a new constitution.

- Identify the processes involved in achieving Confederation.

- Identify the attractions and limits of Confederation in the Canadas, the Maritimes, and the West, respectively.

- Position Confederation as a solution to historically specific issues and as a vision of what the future might hold.

Attributions

Figure 14.1

Charles Connel by Сдобников А. is in the public domain.

Figure 14.2

Behind Bonsecours Market by File Upload Bot (Magnus Manske) is in the public domain.

- Quoted in Ged Martin, "The Case Against Canadian Confederation 1864-1867," in The Causes of Canadian Confederation (Fredericton: Acadiensis Press, 1990), 27. ↵