Chapter 7. British North America at Peace and at War (1763-1818)

7.3 Government

The Proclamation Act was essentially Canada’s first constitution. France never implemented anything of this order. It is noteworthy because of its (limited) tolerance, its demarcation of the Ohioan west, its recognition of Aboriginal title, and its assimilationist agenda. As well, it did not attempt to reproduce in the Province of Quebec the kind of representative councils found in the colonies to the south. Canada was to be governed by governors, much as it had been under France.

Canada under Military Occupation

The first governor was James Murray, a Scot with a long career as a professional soldier who had been at Louisbourg and was Wolfe’s junior commander at Quebec. It was Murray whose forces were defeated in April 1760 at Sainte-Foy and who demonstrated prudence by sitting tight in the citadel until reinforcements arrived to restore full British authority. From 1760 to the Treaty of Paris in 1763, Murray’s mandate was to keep a lid on Canadien resentment, ensure the locals (and their Aboriginal neighbours) did not rise up, and be prepared in case a French fleet suddenly appeared on the St. Lawrence. And, of course, there was always the possibility that France would take back Canada at the treaty table. With all those things in mind and having been taught a lesson at Sainte-Foy, Murray looked for ways to stabilize his situation and that of Canada’s.

There was, to begin, an iron-fist approach. Acadians who had fled the Expulsion to the Gaspé community of Bonaventure were to be rounded up and exiled, not least because they had — unsuccessfully — supported a small French supply fleet heading for Quebec, one that would have inconvenienced if not endangered Murray’s position. Murray was, however, also tough on British troops who mistreated the locals. His strategy was to be both feared and respected. In his own words, Murray believed the Canadiens “hardly will hereafter be easi[ly] persuaded to take up Arms against a Nation they admire, and who will have it allways in their [power?] to burn or destroy.”[1] To that end he allowed widespread use of the French civil law, promoted Canadien militia leaders, and even appointed Franco-Catholics to important offices. He had an understandable suspicion of the clergy: their influence was significant in the Acadian-Wabanaki resistance over the last 20 years.

As for the economy, the British introduced some changes. When the aristocracy and bourgeoisie of France looked at Canada they saw luxurious and highly marketable furs; when the British military looked at their new colony they saw supplies that were needed by navies and armies. Ship masts, pitch and tar, whale and seal oil, iron ore, and potash drew Murray’s attention, as did agricultural potential. These were, however, still staple products, exports onto which little value had been added. Murray’s initiatives made the economy of Quebec wider but it was hardly any deeper. The fur trade continued to dominate, regardless of new initiatives, but even in 1763 it was becoming dominated by British-American merchants whose better credit lines, superior connections to military personnel in the western forts, and access to English-speaking markets in London enabled them to push the Canadien marchands to one side.

Murray’s tenure was brief — he was recalled in 1766 and replaced by Guy Carleton (1724-1808) — but his half-dozen years of authority first in the city of Quebec, then over the whole of the Province of Quebec, established relationships and expectations that had a lasting impact. The clergy, under Bishop Jean-Olivier Briand (1715-1794), seized on the opportunity to preserve their influence, especially over education. Much of Quebec’s Lower Town was rebuilt according to the style of the ancien régime. The seigneurial system, like many other elements of pre-Conquest Canadien society, was encouraged to survive. All this, however, did not diminish the most obvious fact that Canadiens were living under military occupation.

Domination and Adjustment

Assessing the impact of these years has long been a concern of Canadian historians. Some French-Canadian historians argue that the Conquest was followed by the departure (voluntary or otherwise) of leading figures in Canadien society: not just government officials but also key actors in the economy and in society generally. This loss of significant personnel, they argue, led to a parallel collapse in Canadien economic prosperity and social capital. This perspective is referred to as the decapitation thesis.

Other interpretations have focused more on evidence of continuity (as can be seen in the survival of seigneurialism, the Church, and schools) and on the structural changes in the economy that disadvantaged Canadiens. Rather than point to “decapitation,” these historians have argued that Canadien marchands were impacted by the introduction of a new currency and investment environment, the leeching of fur resources from the Pays d’en Haut eastward to the British American colonies and southward to Louisiana, and the replacement of a more oligarchical model of enterprise with one that was more competitive and dominated by large numbers of smaller firms. Patronage from Murray and Carleton may not have favoured the British-Americans very much, but it did so to the disadvantage of the Canadiens.[2]

The greatest controversy of the Murray regime pertains to his failure to create an elective assembly, which eventually cost him his job. By 1765 enough merchants had moved north from the old Thirteen Colonies to change the political dynamics of occupied New France. They set up shop in Montréal and Québec hoping to siphon off wealth from the British military presence and the fur trade. They expected that, as advertised in the Proclamation Act, they would instantly become electors and leading figures in the new British colony. Their expectations were based on the very clauses that froze Murray in his tracks. The Proclamation Act allowed for the creation of a council that would, according to British law, permit only Protestants to hold office. But the total number of Protestants in the Province of Quebec in 1764 was minuscule. Murray estimated there were only 200 Protestant households, and he could not imagine them having authority over 70,000 Catholic Canadiens without provoking a severe backlash. He resisted calls to establish an elected assembly under these circumstances.

Rather than worsen the situation for himself, Murray — perhaps unwisely — pursued land policies that discouraged further British immigration. In doing so, he continued to fall afoul of the British Protestants, especially the Montreal merchants. An alarming array of charges — later thrown out of court — were brought against him and he was recalled to Britain in 1766.

James Murray’s successor, Guy Carleton, was another military man, an officer who served under Wolfe at both Louisbourg and Quebec. Initially he courted favour with the British merchants of the province and split with Murray’s advisors, but within a year he was following a path that Murray had blazed. Both governors looked at the demographics of the province and concluded that the Canadiens were going to dominate the region for the foreseeable future, and there was little to suggest that assimilationist policies would have much effect. They both determined that maintaining the trust and cooperation of the French settlers was preferable to conceding authority to a handful of British-American newcomers who might not have staying power in the colony. Carleton deferred and deflected demands for an assembly and did his best to reinforce the credibility of the seigneurs. Remarkably, Carleton spent four years of his tenure in London, lobbying for constitutional changes that would transition the province out of military possession and into a viable colony.

The Quebec Act, 1774

What the British-American merchants wanted most from a new constitution was an elected assembly. They didn’t get one; instead the Quebec Act entrenched the practice of Murray and Carleton in the form of an appointed legislative council that devised laws in partnership with and at the command of the governor. The new constitution shelved the Proclamation Act’s objective of anglicization and permitted Catholics to hold a greater variety of positions, including seats on the council. It entrenched British criminal law and recognized the Coutume de Paris. As well, British common law played a role in administrative matters and in some criminal cases. The church could resume collecting tithes and seigneurs could once again collect dues.

This was a constitution designed to win the support of the French-speaking majority in the colony, or at least the social and cultural leaders of that majority — the clergy and the seigneurs. Canadiens were unfamiliar with democratic institutions like the assemblies found in New England and the other British-American colonies, and they were accustomed to an oligarchically structured administration run by the King’s representative in Fortress Quebec. But the habitants were none too pleased to see the Church and the seigneurs once again in a position to tax them. The British-American immigrants were predictably livid at the non-elective constitution. Critics in the other British colonies joined in the chorus of voices calling for the familiar freedoms enjoyed to the south. Moreover, British-Americans worried that this rejection of an assembly boded ill for their own institutions. Britain increasingly held with mercantilist control of commerce (through taxes and tariffs); the Americans feared that their assemblies were now in the crosshairs as well.

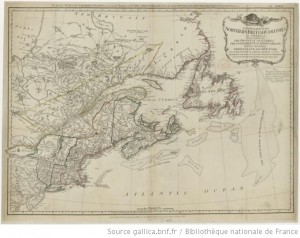

The one feature of the Quebec Act that secured anglo-merchant support in Montreal simultaneously inflamed British-American outrage. The new constitution extended the western boundaries of the Province of Quebec to include the Ohio Valley (see Figures 7.3 and 7.4), which gave the Montreal merchants (British and French) renewed priority and privileges in the region. Fur traders from Pennsylvania, Virginia, and New York — regarded by the Montrealers as interlopers — were now in a weaker position. The Canadien population around Detroit, moreover, made it the third- or fourth-largest town in the province (after Quebec, Montreal, and perhaps Trois-Rivières), so for the majority of the colony’s population, this seemed like an appropriate reunification.

This made the fur traders of Montreal very happy, but the British-Americans regarded it as another act of British perfidy, one that joined a growing list of administrative changes that damaged colonists’ interests. Coming as it did six months after Bostonians dramatically protested a stealthy British tax on tea, some British-Americans interpreted the Quebec Act as vindictive punishment, a sign that the Crown was arbitrary and ill-disposed to the colonies. It was one of several factors that contributed to the breaking of relations between Britain and the Thirteen Colonies and is classed in American histories as one of the Intolerable Acts.

As enlightened and permissive as the Quebec Act appears to be toward Canadien-Catholic society and culture, there is an important caveat to note. The Act came with so-called secret instructions to the governor. When circumstances improved, he was to take steps to anglicize the population. Protestantism was to be favoured; Catholicism might be tolerated but did not extend to approving Papal instructions from Rome. There was to be only one centre of authority, and that was the British Parliament (via Quebec). Assimilation, then, was still on the cards. Within months of the Quebec Act being passed, however, the British administration in the province was doing all it could to ensure the support of the Canadiens in what looked likely to be a disruption in the normal course of colonial business for the next year or two.

Key Points

- Early attempts on the part of the British to govern New France were marked by expectations of cultural assimilation and the extinguishing of Catholicism, but in practice tolerance and inclusion were viewed as necessary to maintaining a loyal population.

- Attempts to integrate the economy of the Province of Quebec into the British mercantile system resulted in the rise of a British/British-American merchant class in Montreal and Quebec where they were able to out-compete the Canadien marchands.

- The anglophone community countered the pragmatic compromises of Governors Murray and Carleton with demands for greater liberties for themselves, fewer for the Canadiens, and a greater role in governing the colony.

- The Quebec Act was an articulation of Carleton’s policy of cautious tolerance and inclusion; it included provisions for British common law and the continuance of the Coutume de Paris in areas like seigneurial law. It also provoked a hostile response from the Americans.

- “Secret instructions” to the governor revealed that the policy of tolerance was meant to be a temporary measure and that cultural assimilation of the French was a long-term goal.

Attributions

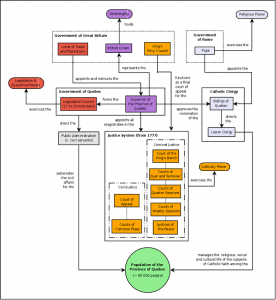

Figure 7.2

Constitution-of-quebec-1775 by Mathieu Gauthier-Pilote is used under a CC-BY-SA 3.0 license.

Figure 7.3

Province of Quebec 1774 by Harfang is in the public domain.

Figure 7.4

A general map of the northern British colonies in America by File Upload Bot (Magnus Manske) is used under a CC-BY 2.0 license.

Long Description

Figure 7.2 long description: A chart describing the flow of authority between Britain and Canada according to the Quebec Act. The British Crown held sovereignty and was represented in Canada by the Governor of the Province of Quebec. In addition to the Crown, Great Britain’s government was made up of the Lords of Trade and Plantation, who appointed and instructed the governor of Quebec, and the King’s Privy Council. The King’s Privy Council functioned as the final court of appeal for Quebec’s justice system. The governor of the province of Quebec had a number of responsibilities, including appointing the justice magistrates, forming the legislative council in Quebec, and approving the nomination of the Bishop of Quebec by the Pope. The Governor and the Legislative council, which consisted from 17 to 23 members, made up the government of Quebec. The legislative council exercised legislative and executive powers and directed the public administration and civil servants, who administer the civil affairs for the population of the province of Quebec, which at the time had about 90,000 people. The Justice system was divided into civil and criminal justice systems, which exersized judiciary power. The civil justice system included the Court of Appeal and the Courts of Common Please. The criminal justice system included the Court of the King’s Bench, the Courts of Oyer and Terminer, the Courts of Quarter Sessions, the Courts of Weekly Sessions, and Justices of the Peace. The religious, social, and cultural life of subjects of the Catholic faith was managed by the Lower Clergy, who were directed by the Bishop of Quebec. [Return to Figure 7.2]

- G. P. Browne, “MURRAY, JAMES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003). Accessed August 26, 2014, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/murray_james_4E.html . ↵

- José Iguartua, "A Change in Climate: The Conquest and the Marchands of Montreal," Historical Papers (1974): 115-34. ↵