Chapter 6. Intercolonial Rivalries, Imperial Ambitions, and the Conquest

6.8 The Fur Trade in Global Perspective

The rise of the fur trade in the colonial context is a story of both supply and demand. The aristocracy of Europe always was a reliable market for fur, a product that was viewed as functional, fashionable, and even regal depending on the specimen and the wearer. European fur-bearing animal stocks, however, were being depleted by overhunting and by competition from expanding farming frontiers for territory. Beavers were effectively extinct in the British Isles by the 16th century; in France their numbers were similarly reduced.

Beavers and Bourgeois

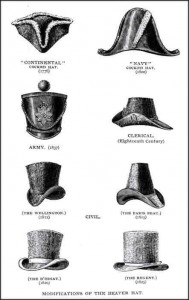

Meeting royal and aristocratic demand for furs became the task of merchants. Their principal source was Russia, but the discovery that furs could be obtained much more cheaply from North America reoriented the supply lines. Merchants on the Atlantic coast of Europe parlayed what they earned in the fisheries into fur-trading operations, and the wealth they gained fuelled the rise of a merchant class that would, itself, demand more furs. Soon the wealthiest merchants were sporting fur hats and trim on their coats. The top hat (or stovepipe hat) didn’t appear until the 19th century, but its forerunners were symbols of rising merchant status, adding height to the wearer and acting as a kind of mercantile crown. This meant that even if demand for furs among the gentry was fully satisfied, there was a growing and effectively insatiable market in the cities of Western Europe where a new class of citizen — the bourgeois or bourgeoisie — was sufficiently prosperous and influential to drive the industry forward.

The French were the first into the fray, at least officially. Five years after Champlain struck a commercial and military alliance with the Algonquian and Wendat, the Dutch began to explore the possibilities of a trade along the Hudson River. This river marked the approximate boundary between Mohawk (Haudenosaunee) and Mahican territories. It connects (with a few portages) the French settlements on the St. Lawrence via Lake Champlain with the Dutch and (later) British settlements of New Amsterdam. Furs from Fort Orange (now Albany, New York) were transferred downriver to New Amsterdam (New York after 1667), most of which seemed to be coming from the lands around Lake Ontario. All of the North American colonies, even the Carolinas, produced some furs for markets in Europe, and there was a lively trade in furs and deer hides out of Louisiana, but the best furs were to be obtained north of the Great Lakes.

What Europeans wanted most was treated pelts that had been cleaned of the longer guard hairs, leaving more of the rich felt exposed and ready for use.[1] But catching, killing, skinning, and tanning beaver hides was a labourious process and that left the guard hairs in place. Aboriginal peoples who had already done all the work of trapping and processing inadvertently added value: by using the pelts as blankets or clothing they wore off the guard hairs. This was a feature of the fur trade that required traders (French or Aboriginal) to probe deeper into the continent in search of new supplies of worn pelts, which explains the speed with which New France penetrated the river systems of North America.

Furs and Frontiers

As Europeans looked to their Aboriginal trading partners to access pelts from farther inland, particularly in the North where colder climates produced healthier pelts, the fur trade invaded all the early colonies and dictated their size and shape. While Virginia and the other plantation and farming colonies set their foundations in concentrated areas, New France stretched its network — and then its forts, posts, and influence — farther into the interior of North America so that virtually all the major rivers and lakes of the continent were contained within its sphere of commercial influence. The English response was to attempt, repeatedly, to capture the French positions on the St. Lawrence, thinking that the fur supply would simply continue to flow downstream and into their hands. In the late 1600s the English tried a different tactic, encouraging their Haudenosaunee allies to weaken the French-Algonquin supply lines. Having pressed the French from the south, the English then turned to the far north (see Chapter 8.)

From the 1670s, then, the French faced the English on two fur trading frontiers and found themselves engaged in a long-running battle with the Haudenosaunee, who were acting in their own interests and, occasionally, as clients/allies of the English. Much of the conflict between France and England in the colonial theatre related to this competition.

Key Points

- The North American fur trade was a response to declining populations of fur-bearing animals in Western Europe and the cost of purchasing and importing furs from Russia.

- The qualities most sought after in beaver and other fur pelts necessitated trading farther into the interior of the continent, thus propelling New France outward from the St. Lawrence.

Attributions

Figure 6.6

Eight different styles of beaver hats by ~Pyb is in the public domain.

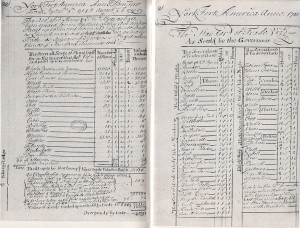

Figure 6.7

Hudson’s Bay Company. List of skins traded by Kürschner is in the public domain.

- Harold A. Innis, The Fur Trade in Canada: An Introduction to Canadian Economic History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1966):12-14. ↵