Chapter 6. Intercolonial Rivalries, Imperial Ambitions, and the Conquest

6.11 The Seven Years’ War

If one looks at North American history only through the lens of British and French interests, then it is true that most of the imperial wars to 1755 began as offshoots of European conflicts. From an Aboriginal perspective, this was far less often the case. Certainly the War of the Austrian Succession was, in the Maritimes, much more about the ongoing Wabanaki resistance than transatlantic affairs. The Seven Years’ War provides another example of this pattern.

Conflict in the Ohio Valley

Led by George Washington (1732-1799), a scion of the Virginian gentry and shareholder in a speculative land company, a Virginian party set out in 1753 to request that the French relinquish their position in the Ohio Valley. The result was intensified French activity in the region. The following year Washington returned (once again under orders from Virginia’s governor) and ambushed a French detachment. The French response (along with several of their Aboriginal allies) was to pursue and capture Washington at Fort Necessity before releasing him with a clear message for Virginia: the Ohio Valley was beyond their grasp.

To this point in time, British conflict with the French had focused on the frontiers between New England and Acadia, New York, and Canada. The other British colonies had not been involved and there were occasions, such as during the War of the Austrian Succession, where New England struggled on its own without even the help of New York. British American population and economic growth by 1754, however, had reached a point where many of the largest colonies felt friction with New France. Georgia in the south was pinched between Florida and Louisiana; Virginia was both powerful and rich as well as increasingly cramped on the tidewater side of the Appalachians; New York’s ambitions for the west, along with those of Pennsylvania, pulled it into conflict in the Ohio; New England and Nova Scotia, as we have seen, continued to wrestle with Wabanaki Confederacy attacks and uncertainty about the Acadians and the future of Louisbourg. It was, perhaps ironically, the shared French threat that first brought together the disparate and disunified 13 British American colonies in an effort to work out solutions to common problems (and thus pave the way for further collaborations in 1775).

The French and Indian War

The American name for the Seven Years’ War — the French and Indian War — reflects their perception that this was a battle against two old foes, and not merely one. Despite a massive imbalance in population numbers that favoured the British colonies (there were 20 British Americans for every resident of New France), the French colonies held their own. They did so principally by having better Aboriginal allies. The Council of the Three Fires — in particular, the Ottawa and the Potawatomi — were of special importance. The Haudenosaunee might have challenged French activity in the Ohio, but the British refused to support them against the expanding chain of French military/trading forts running from Lake Ontario to New Orleans.

Indeed, the Haudenosaunee were a powerful third force in the Ohio Valley. Since the Beaver Wars they had been extracting tribute from smaller client nations to the south, including the Shawnee and the Delaware. Recognizing that neither the French nor the British fully respected their interest in the region, they sought to whipsaw the Europeans against one another by means of a policy of “aggressive neutrality.”[1] This strategy presented its own challenges, not least because Haudenosaunee control of the region was gradually shifting. Decades of human depopulation and warfare had allowed some of the local ecosystem to recover, making it highly desirable hunting grounds once again. Other Aboriginal peoples were, as a consequence, returning to the Haudenosaunee territories (to the chagrin of the Five Nations). These Aboriginal “colonists” in the Ohio were at odds with one another, as well as with the League and the British-Americans. Shawnee and Delaware resettlements in the Ohio were rubbing up against Miamis, Mascouten, and Kickapoos from west of the Great Lakes (they had shifted eastward to capitalize on trade with the British), and Wyandot (Wendat/Huron) remnants were huddled around the west end of Lake Erie. One scholar describes it as “a world of multiethnic villages outside of the French alliance and beyond the authority of the Iroquois Confederacy.”[2] There was, therefore, little Aboriginal solidarity and quite a lot of negotiable loyalties in relation to alliances with the Europeans, Canadiens, and Americans.

From 1754 to 1757 the war mostly tilted in favour of New France. For the first two years it was exclusively a colonial affair, but with the outbreak of war in Europe in 1756 new strategies emerged. The British, under Prime Minister William Pitt, believed they could tie up French armies in Europe and make use of their superior navy to harass the colonies of France abroad. France by contrast, under Louis XV, stuck to the tried-and-tested strategy of conceding little and banking on a good outcome at the treaty table. After all, return to the status quo ante bellum had worked well for France in one treaty after the next.

European War in North America

Nevertheless, France did commit regular troops to New France under the leadership of Louis-Joseph, the Marquis de Montcalm (1712-1759) in 1756. This was following a career marked by defeats and retreats in Europe. By that time the governor general of New France, the born-in-Canada Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil de Cavagnial (1698-1778), had scored several important defensive victories against the British and the British Americans. In the Ohio and along the Great Lakes, Vaudreuil’s forces proved consistently more able than those of the British. The defeat of the British-American General Braddock in the Ohio in 1755 was a major coup for New France. Vaudreuil’s success stemmed from effective deployment of Aboriginal militias. Both Vaudreuil and Montcalm’s aide-de-camp, Louis Antoine de Bougainville, promoted the use of forest combat conducted by their Aboriginal allies and Canadien irregulars. As Bougainville explained, “In this sort of warfare it is necessary to adjust to their ways.”[3] The only offensive the British and their colonists were able to mount successfully was that against Fort Beauséjour, mentioned above.

Montcalm’s arrival turned the colonial defence from a successful strategy of harrying the British with surgical strikes against their frontier to one of sit-and-wait. The new commander was more comfortable with set-piece battles, regarded Aboriginal warfare as uncivilized and unworthy, and demonstrated an unwillingness to press his foot down on an enemy’s throat. By 1758 he had lost the Ohio Valley which, in any event, he regarded as secondary to the importance of securing the St. Lawrence Valley. More than that, Montcalm went out of his way to undermine the reputations of his rival Vaudreuil and his friend, the intendant François Bigot. In 1758 Montcalm’s intrigues in the palaces of Paris paid out and he was promoted to lieutenant-governor and thus placed above Vaudreuil in the command of forces in Canada.

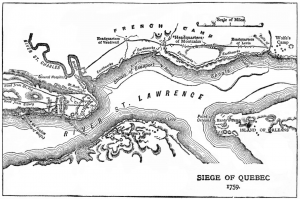

In 1759 the Royal Navy swept up the St. Lawrence and confronted Montcalm at the citadel of Quebec. Even in this instance, Montcalm’s instincts proved flawed. He thought (wrongly) that the river itself would confound the British, who were unfamiliar with its currents and hazards. He neglected to defend the height of land across the river from Quebec, which allowed the British to bombard the city into dust.[4]

The British forces, under the command of Major General James Wolfe (1727-1759), reached the Île d’Orléans in mid-June hoping for a quick victory. Although his army was smaller than he’d hoped, Wolfe nevertheless had some 7,000 troops and the support of nearly 200 vessels. Exploratory attacks on Canadien positions failed repeatedly, as had the relentless shelling of the Lower Town. By mid-September Wolfe’s troops were burning out the Canadien farmers, destroying their crops and thousands of homes in the hope of creating pressures on Quebec that might pay off the following year. Many of his troops had deserted, morale was low, illness was depleting the ranks, freeze-up of the river was quickly approaching, and Wolfe himself was convinced that his mission was a failure. He was ready to abandon the attack and let the French and Canadiens struggle through a winter with limited food supplies, which he hoped would soften them up for a springtime assault.

The almost chance discovery of a landing point at a cove called L’Anse-au-Foulon was seized upon by Wolfe. On September 13, 1759, he assembled his troops on the Plains of Abraham. At this point, Montcalm had several options: wait for his reinforcements to arrive along Wolfe’s western flank and pin down the British; send out snipers along with Aboriginal and Canadien militiamen to gun-and-run until Wolfe’s troops were depleted and/or demoralized; stay in the citadel and wait out a British force that had little appetite or ability for a long siege in the face of oncoming winter (and just hope for the arrival of the French fleet); or march out onto the field and confront Wolfe. He chose the last of these.

The Blame Game

Louis du Pont Duchambon de Vergor was born in France in the year of the Treaty of Utrecht and joined the French military in 1730. The whole of his military career was spent in New France. His principal talents were skimming money out of the colonial purse, serving as “pimp” to the intendant François Bigot, privateering a bit on the side, and underperforming spectacularly in his military duties. Mme. Élizabeth Bégon de la Cour (1696-1755), a Montreal woman of considerable influence and even more wit, described Vergor as “the most dull-witted fellow I have ever met but he knows all the angles.”[5] This was, however, the man left in charge of Fort Beauséjour in 1754 and responsible for its fall to a British-New England force a year later. More than that, his actions played a role in precipitating the Acadian expulsion.

Low on credible troops, Vergor persuaded local Acadians to assist in the defence of the fort by promising that, if they were captured by the British, he would protect their official neutrality by claiming to have forced them into a compromised position. A two-week long siege, mutiny among the Acadians, and an exploding cannonball sealed Beauséjour’s fate: on June 16 Vergor ran up the white flag of surrender. The outcome for the Acadians who could not escape capture was exile, their participation in the battle taken by the British as confirmation that the Acadians were merely hiding behind a façade of neutrality. Vergor’s defence of Beauséjour was certainly anything but gifted. He was packed off to Canada where, in 1757, he walked away from a court martial thanks to his friend Bigot, who paid off the jury. For the next two years Vergor played a minor role in the defence of Canada, and the late summer of 1759 found him in charge of a sentry post at the Anse au Foulon. It was there, in the early hours of September 13, that Wolfe’s forces found a path from the river to the Plains of Abraham, surprised the inattentive Vergor and his men, and assembled for the battle with Montcalm. Having lost Acadia, Vergor might be blamed for the fall of Canada as well.[6]

Victory, it must be added, was by no means guaranteed to the British troops that day. Wolfe seized on the worst position he could have selected and stayed there, despite better options. Montcalm’s insistence on attacking in columns rather than in lines, on using regular troops and set-piece tactics rather than letting loose Vaudreuil’s shock troops, cost the French dearly. It is a pivotal moment in the history of Canada, and yet it unfolds so badly that its two principal actors — Wolfe and Montcalm — were both killed or mortally wounded in battle, something that rarely happened in European warfare. Considering the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, historian William Eccles wrote many years ago that “perhaps the most overlooked determining factor in history has been stupidity.”[7]

From Defeat to Conquest

To be sure, the war was far from over in September 1759. The bulk of the French troops retreated to Montreal where they licked their wounds. The Chevalier de Lévis, Montcalm’s successor, had 7,000 troops with him in April 1760 when he confronted a much smaller and rather sickly British army at the Battle of Sainte-Foy. The French won easily but they could not retake Quebec, and the hoped-for French fleet failed to arrive (having been sent to the bottom of the sea by the Royal Navy at Quiberon Bay). Instead, British ships reached Quebec when the river ice melted and in September, one year after the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, Montreal fell.

A great deal has been written about this battle because it represents for many a turning point in the history of Canada. It is the moment at which Canada fell to the British; it is the moment of “the Conquest.” Of course it was not: that happened at the treaty table four years later. What Wolfe accomplished on the Plains of Abraham might well have been undone at the Treaty of Paris. Britain decided that, strategically, Canada was a better choice than one of its other prizes: the sugar colony of Guadeloupe. Keeping Canada would put an end to the hemorrhaging expense of continuous colonial war in North America. This would, of course, entail maintaining a northern colony populated by hostiles, so it was not entirely positive from the perspective of Britain. France, for its part, agreed with the decision. Canada would be hard for Britain to hold and the removal of French influence from the Ohio would be like unstopping a drain: the American colonists would become difficult to contain. Being allowed to keep the lucrative West Indian island must have seemed to the French negotiators like the best possible outcome. Besides, Quebec had fallen before in colonial struggles, and it had always been restored, a possibility that could be held out to the Canadiens and those business interests in La Rochelle and Breton whose livelihoods were closely tied to that of the colony. In other words, France had not entirely given up on Canada, nor had Canada given up entirely on France.[8] As for the British, winning New France was one thing, but holding it was another.

The Legacy of the Seven Years’ War

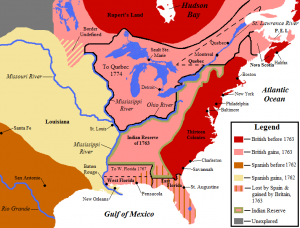

First, New France was at an end. The British claimed everything north of Florida. France gave Louisiana west of the Mississippi River to its ally Spain in compensation for Spain’s loss to Britain of Florida (which Spain had handed to Britain in exchange for the return of Havana, Cuba). France held on to western Louisiana until 1803, but otherwise its colonial presence north of the Caribbean was reduced to the tiny islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon. Britain’s position as the dominant colonial power in the eastern half of North America was confirmed.

Second, French absolutism was in trouble. The war in Europe had been expensive and the country was impoverished as a result. Many factors contributed to the French Revolution in 1789, and the Seven Years’ War was one of them. This situation curtailed any hope of a restoration of French power in North America. It also led to further global conflicts and, more importantly, to the rise of secular and democratic modern society — not just in France but all around Western Europe and across the Atlantic.

Third, the outcome boded ill for Aboriginal peoples. For many of the nations, the elimination of French power in North America meant the disappearance of a strong counterweight to British expansion. Most obviously the Haudenosaunee strategy of whipsawing the two European powers against one another was eliminated. Pressures increased on Native populations from the Atlantic seaboard through the Ohio and Mississippi, producing waves of refugees as one population after the next was dispossessed. These westward-moving exiles, in turn, pushed other Aboriginal peoples along as well. Tensions built swiftly and produced further conflict.

Fourth, the British American colonies felt entitled to the spoils of war. The Ohio Valley lay ahead of them, unopposed by French forts (regardless of Aboriginal resistance). More to the point, the British regime was not certain that it was ready to unleash colonial America from behind the Appalachian barrier. The farther the colonies spread, the more likely it was that Britain would be called on to defend them against Aboriginal attacks. The cost of the Seven Years’ War was high enough and Britain’s treasury needed time to recover. As well, Britain feared that an open frontier would only make the Americans more difficult to govern.

Finally, the war had provided an opportunity for militiamen from New England through Virginia to cut their teeth on battle. George Washington, for one, had gone from a brash and inexperienced soldier at age 22 to a far more confident and mature military leader, thanks to the opportunities provided him by service to Britain. The Seven Years’ War was the first occasion in which the Thirteen Colonies had pursued common goals, and it gave a boost to their ambitions.

For Acadia and Canada the end of the war brought uncertainty and fear. Acadian society was shattered by the Expulsion. Its outposts on the western mainland of Northumberland Strait and in the new British colony of Prince Edward Island struggled to survive under the new administration. No doubt more than a few hoped for another exchange of imperial masters, but that wheel had stopped turning. The Canadiens, for their part, continued to hope for relief from France while watching nervously the deportation of the Acadians.

The “land hunger” that had propelled British Americans into the Ohio and into wars against the Wabanaki Confederacy was to have very direct consequences for Nova Scotia and Canada. Some of these would be felt immediately as migrants poured (in smallish numbers) into both colonies. The trickle, however, would become a torrent in less than a generation.

Key Points

- The first intercolonial conflicts associated with the Seven Years’ War took place in the Ohio Valley and were instigated by Virginian expansionism into French/Aboriginal territory.

- The involvement of Virginia presaged a war between New France and the whole of the British colonies, rather than just New England, Nova Scotia, or New York.

- British success was predicated mainly on a vastly larger colonial population and a significant commitment of military resources.

- The Conquest of Canada occured at the negotiating table.

- The outcome of the Seven Years’ War had almost immediate implications for relations between Britain and its original colonies and for the French absolutist regime. It also boded ill for Aboriginal peoples in the Ohio Valley and beyond.

Attributions

Figure 6.14

Fort de La Présentation by Charny is used under a CC-BY 3.0 license.

Figure 6.15

French and Indian War by Hoodinski is used under a CC-BY-SA 3.0 license.

Figure 6.16

Fortress Québec by Tango22 is in the public domain.

Figure 6.17

Après guerre by Jeangagnon is in the public domain.

Figure 6.18

Map of Montreal 1749 by Jeangagnon is in the public domain.

Figure 6.19

NorthAmerica1762-83 by Creysmon07 is used under a CC-BY-SA 3.0 license.

- Fred Anderson, Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766 (London: Faber and Faber, 2000), 16. ↵

- Colin G. Calloway, One Vast Winter Count: The Native American West before Lewis and Clark (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006), 331-2. ↵

- Ibid., 340. ↵

- W. J. Eccles, “MONTCALM, LOUIS-JOSEPH DE, Marquis de MONTCALM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol 3 (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003). Accessed January 12, 2015, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/montcalm_louis_joseph_de_3E.html . ↵

- Céline Dupré, “ROCBERT DE LA MORANDIÈRE, MARIE-ÉLISABETH,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol 3 (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003). Accessed December 13, 2014, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/rocbert_de_la_morandiere_marie_elisabeth_3E.html . ↵

- Bernard Pothier, “DU PONT DUCHAMBON DE VERGOR, LOUIS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003). Accessed December 13, 2014, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/du_pont_duchambon_de_vergor_louis_4E.html . ↵

- W.J.Eccles, "The Battle of Quebec: A Reappraissal," Essays on New France (Oxford: OUP, 1987), 133. ↵

- Helen Dewar, "Canada or Guadeloupe?: French and British Perceptions of Empire, 1760-1763," Canadian Historical Review 91, no.4 (2010): 637-60. ↵