Chapter 13. The Farthest West

13.11 Summary

The territory that became British Columbia joined the Canadian federation in 1871. Until that time, however, Canada was very distant and rather foreign and mostly irrelevant. The orientations of the Pacific Northwest were toward Asia, the Pacific Islands, Mexico and Chile, and round Cape Horn to England. For the many Aboriginal peoples and cultures in the region, Canada was a country with which they had effectively no contact and hardly more knowledge. The challenge, then, is to understand these pre-Confederation years as an era in which other priorities and possibilities presented themselves.

The colonies of British Columbia and Vancouver Island were expensive to maintain, especially as the gold rush ended and the population diminished. From a peak of 10,000 the Cariboo population fell to about 1,000 by 1870. It is estimated that there were only about 2,000 Chinese left in the colony. The Cariboo Wagon Road had cost the mainland colony dearly and pitched it into debt. The capital at New Westminster — dominated by merchant houses, a colonial elite, and a Royal Engineers’ community ensconced at Sapperton — was desperate to hold onto its administrative role.

In 1866 the mainland and the island colonies were consolidated. Bits and pieces of New Caledonia, the Stikeen Territory, the Colony of the Queen Charlotte Islands, and the post-Rupert’s Land North-Western Territory had been gradually grafted onto British Columbia and this was the final piece. And — much like Lower Canada in 1841 — Vancouver Island inherited British Columbia’s debt.

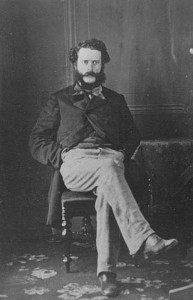

The political culture that developed west of the Rockies was, like the population, multifaceted. There were powerful British themes promoted by the Colonial Office alongside Canadian traditions brought west by Upper Canadians like the reformer John Robson. There was a democratic tradition that can be ascribed, in part, to the Americans and Nova Scotians, such as Amor de Cosmos, a harsh critic of the squirearchy in Victoria. The HBC’s tradition of hierarchy and discipline was increasingly caricatured as a West Coast variant of the Family Compact. It was in some respects — in terms of the close bonds between the chief administrator and the members of the Victoria elite — even more of a family compact than ever existed in Upper Canada. Well-positioned individuals like Joseph Trutch were vitriolic in their opposition to democratic reforms. The four years after Confederation in the East would see the colonists in British Columbia pulled in different directions.

While that debate was underway, Aboriginal communities continued to stagger from hardship to hardship. As early as 1852 Douglas had witnessed privation and perhaps starvation among the Lekwungen with whom he had signed an early treaty. They were no longer at the centre of the local economy, a change that had taken place in a matter of 10 years.

It is possible to argue that the fur trade on the West Coast was a period of mutual benefit. This is the position taken by Robin Fisher in his landmark book Contact and Conflict, in 1977.[1] He argues that both sides profited from the trade and whatever cultural change occurred in Aboriginal societies was mediated and controlled by Aboriginal peoples themselves. The absence of missionaries and/or imperial power until the 1840s is at the heart of this argument. Other historians have taken the position that the epidemic waves beginning in the 1780s, if not earlier, meant that the odds were stacked against Aboriginal ability to adapt. Still others point to the extent of Aboriginal authority in the fur trade, the extent to which indigenous people were able to exploit newcomer dependence, and the ways in which Aboriginal peoples managed newcomer behaviours as a sign of ongoing autonomy.

The gold rush of 1858 and the smallpox epidemic of 1862 rendered much of this moot. A territory over which Britain and Spain were once prepared to go to war had so fallen off the European radar that the events of 1858-63 threw it all up in the air again. As Douglas and his colleagues in the HBC retired from public life and passed away, links with the pre-gold rush past evaporated. For the British Columbians of 1858-1871 there was not much in the way of a history to their colony, and what history they saw they generally didn’t like. The future was the thing, and they would sacrifice much to get there.

Key Terms

Cariboo Wagon Road: A road constructed from 1860 to 1885 to connect the Lower Mainland of British Columbia with the Cariboo goldfields. The original 1860-63 road ran from Port Douglas at the north end of Harrison Lake via Lillooet to Clinton and then north across the Cariboo Plateau to Alexandria. An amended version in 1865 connected Yale to Ashcroft and then Clinton and the older road, having passed through the Fraser Canyon.

Chilcotin War: Also referred to as the Chilcotin Massacre, Chilcotin Uprising, and Bute Inlet Massacre. Occurred in 1864 when Tsilqot’in people asserted their control of their ancestral territory by murdering several members of a road-building crew and some colonists. The colonial authorities responded with a fruitless and expensive campaign that only ended when several of the Tsilqot’in leaders presented themselves for negotiations and were summarily arrested and subsequently hanged.

Church Missionary Society (CMS): Established in London, England, in 1799. Began sending Anglican missionaries to Rupert’s Land in the 1820s. In 1857 William Duncan was dispatched to the northwest coast on behalf of the CMS.

Douglas treaties: Also known as the Fort Victoria Treaties, 14 agreements between the Colony of Vancouver Island (under the leadership of James Douglas) and Aboriginal communities. These were one-time land purchase treaties that protected Aboriginal village sites and fields, as well as access to resources.

Fifty-Four Forty or Fight!: Slogan coined in 1844 or 1845 by American expansionists eager to claim the whole of the Oregon Territory to the Alaska panhandle (54°40’N).

Fort George: The name of two forts in the Pacific northwest. The first replaced the American Fort Astoria near the mouth of the Columbia River (at what is now Astoria, Oregon), and the second was established in 1807 by Simon Fraser at the site of what is now the city of Prince George, British Columbia.

Fort Rupert: Located at the north end of Vancouver Island near modern-day Port Hardy. Established by the HBC as a coal harvesting/mining experiment. It is an important Kwagu’ł community today and should not be confused with the city of Prince Rupert, much farther north on the mainland, nor with Waskaganish in northern Quebec, which was formerly called Fort Rupert.

Fort Vancouver: An HBC fort established in 1824-25 about 60 kilometres up the Columbia River from Fort George (formerly Fort Astoria). Now the site of the city of Vancouver, Washington. The city of Vancouver, British Columbia, was never a fort and there is no relation between the two other than the name.

Fraser River gold rush: A mining boom beginning in 1858 characterized by large numbers of independent prospectors using simple mining technologies to extract gold flakes, dust, and nuggets from the Fraser River. This gold rush was superseded by better finds in the Cariboo in the 1860s.

gold fever: Term used to describe the opportunistic individualism found in gold rushes. Gold was discovered and mined by independent prospectors around the Pacific Rim beginning in Australia from the 1840s, California from 1848, a brief flurry in Haida Gwaii in the 1850s followed by the British Columbia rush from 1858-63, and New Zealand in the 1860s. After Confederation there were smaller rushes in British Columiba and these were surpassed by the Klondike/Alaska gold rush of 1896-1909. The close succession of gold rushes meant that many of the personnel in the goldfields had experience in other gold rushes and many of the gold field institutions followed in their wake.

gunboat diplomacy: The achievement of colonial political goals in dealings with Aboriginal communities by means of superior naval firepower.

land-based fur trade: Refers to the HBC’s strategy in the 1830s to establish permanent fur-trading establishments on land, rather than rely on ships cruising the coast looking for trade. (See maritime-based fur trade.)

Manifest Destiny: Widespread belief in the United States during the 19th century that America was destined — that is, intended by God — to conquer and occupy most if not all of North America.

maritime-based fur trade: The European and American practice dating from the 1770s of trading up and down the coast from ships, rather than establishing fixed positions on land.

Nootka Crisis: A diplomatic incident due to conflicting between Spanish and British claims to sovereignty and the right to trade along the Pacific northwest coast. The disagreement was resolved in the Nootka Conventions of 1790-1794. Despite the negotiations taking place at Yuquot, Mowachat interests and claims to sovereignty were disregarded.

Oregon Treaty, 1846: Settled the boundary between the United States and the British territories west of the Rockies at 49°N.

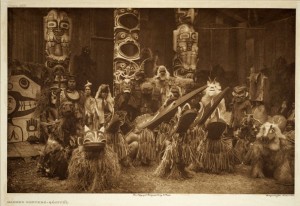

potlatch: An Aboriginal ceremonial event common across the Pacific Northwest. Involves the giving of gifts by the host to mark a life event like an inheritance or succession.

Puget Sound Agricultural Company (PSAC): Established in 1838-39 by the HBC to provide food for its posts and surpluses for sale to the Russian American Company.

Russian American Company (RAC): Chartered in 1799, the RAC was principally focused on the sea otter fur trade and also established outposts in Alta California and Hawaii.

sea otter pelts: On the West Coast the principal fur traded by Aboriginal communities to European and American buyers for sale in the Chinese marketplace.

Short Answer Exercises

- How did Aboriginal peoples on the northwest coast and on the mainland respond to contact with Europeans from the 1740s to the 1840s?

- What impacts did the sea otter trade have on northwest coast cultures?

- How did Britain emerge as the leading imperialist presence on the West Coast north of the Columbia River and south of Alaska?

- In what ways was the fur trade west of the Rockies different from what occurred to the east?

- How was the maritime fur trade on the northwest coast different from the land-based trade (both on the coast and in the Interior)?

- What were some of the demographic impacts of contact on the northwest coast from the 1780s to the 1860s?

- Why did the HBC move its operations to Fort Victoria and what were the expectations of both London and the local indigenous communities?

- In what ways did the HBC diversify its activities on the northwest coast after the 1830s?

- Why was there a coal industry on Vancouver Island in the 1850s and 1860s?

- How did Aboriginal societies resist colonialism?

- How did the gold rush impact colonial development?

- What was the demographic character of the gold rush?

- What was the character of local colonial government from the 1840s to 1870?

- How did Native-newcomer relations change from the 1830s to the 1860s?

Suggested Readings

- Barman, Jean. “Taming Aboriginal Sexuality: Gender, Power, and Race, 1850-1900.” BC Studies,115/116 (Autumn/Winter 1997): Audio. http://bcstudies.com/?q=full-site-search&search_api_views_fulltext=Taming+Aboriginal+Sexuality%3A+Gender%2C+Power%2C+and+Race+in+British+Columbia

- Belshaw, John Douglas. “The West We Have Lost: First Nations Depopulation.” In Becoming British Columbia: A Population History, 72-90. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2010.

- Harris, Cole. “The Native Land Policies of Governor James Douglas.” BC Studies 174 (Summer 2012): 101-122.

- Perry, Adele. “Hardy Backwoodsmen, Wholesome Women, and Steady Families: Immigration and the Construction of a White Society in Colonial British Columbia, 1849–1871.” Histoire Sociale/Social History 33, no.66 (November 2000): 343-360.

- Wickwire, Wendy C. “To See Ourselves as the Other’s Other: Nlaka’pamux Contact Narratives.” Canadian Historical Review LXXV, no.1 (March 1994): 1-20.

Attributions

Figure 13.35

Showing of masks at Kwakwaka’wakw potlatch by User:Deadstar is in the public domain.

Figure 13.36

Portrait de John Robson by Digging.holes is in the public domain.

- Robin Fisher, Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations, 1774-1890, 2nd ed. (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1992). ↵