Chapter 5. Aboriginal Canada in the Era of Contact

5.4 Strategic Encounters

Karl Marx, the German philosopher and historian, wrote that “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please.”[1] We encounter the world not as we would like it to be, not “under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.” Aboriginal peoples in North America were not simply acted upon, they were actors. They made their history by making their own choices, but they did so in the context of early globalization and all the while carrying the burden of their own histories. In some historical accounts of the era, Aboriginal people confront the technological and organizational advantages of Europeans and generally come off badly. Consider that Aboriginal people were engaged in the very human business of confronting and wrestling with their own history on a stage where Europeans suddenly had a role. This complicated relationship was most often expressed in the language of trade and warfare.

Commerce

The measure of the extent and intensity of Aboriginal commercial networks is made clear by looking at the proto-contact era. We know when Europeans officially arrived in the Americas and when official voyages took place from Spain, France, England, and other countries. And we know that unofficial and irregular contact involved the fishing and whaling fleets of the north Atlantic and that some of those arrived before the chartered explorers did. We can deduce from the official reports some aspects of the contact experience in those instances. What is more difficult to know is the extent of first contact. How far inland and upriver did the ripples of contact spread?

By 1535, Aboriginal peoples of the Maritimes and the Gaspé had identified the trading opportunities represented by European sailing ships. The peoples of the Gulf of St. Lawrence were integrating European iron and copper products into their hunting and domestic toolkits. These products had value in and of themselves, but they also had commercial value in the existing indigenous marketplace. Long before Europeans established trading posts, Aboriginal merchants were meeting at places at or near Tadoussac to exchange exotic goods for furs. By 1580, European goods were showing up in Wendat villages — a full quarter century before Champlain met with Outchetaguin, the first Wendat representative to come calling on the French at Quebec.

Aboriginal peoples from the Mi’kmaq through the Gaspé Iroquois to the Laurentian Iroquois were eager to trade with Cartier when he arrived. Twenty fur-laden Mi’kmaq canoes paddled out to meet Cartier’s boats — they weren’t afraid and they knew that the Europeans were open to trading. As a means of attracting the attention of the French, the “Gaspesians” (as they’ve come down to us) waved long poles bedecked in furs. Clearly they knew what caught the visitors’ fancy, in more ways than one: Cartier noted that the locals were careful to have their womenfolk retreat to safety away from the foreshore as French ships approached, from which Cartier deduced that there had been incidents of sexual assault of some kind. Aboriginal management of these encounters took several forms during Cartier’s visits. On his second voyage, Donnacona (the headman at Stadacona) tried to prevent Cartier from leaving so that his village, through control of Cartier, could by extension control and dominate the French-Aboriginal trade.

The fur trade even at this early stage allowed Aboriginal people access to metal tools that would make their lives easier. Steel knives, copper pots, and kettles replaced stone tools and ceramic pots and woven baskets. Iron axes replaced stone axes. These changes advanced the ability of Aboriginal people to kill their food and/or their enemies; they facilitated food preparation; and nets, firearms, and hatchets made hunting easier and more productive. These labour-saving technologies helped them acquire more and better food, increased mobility (a copper pot is the epitome of portability), and allowed them to clear forests faster to plant more crops. In the arms race between Aboriginal peoples, a metal-tipped arrow was an important advantage in its own right. Riflery — which came later and was often dangerously unreliable but very dramatic — might further tip the scales. Aboriginal women in particular benefited from metal cooking utensils, iron scraping tools, and sewing needles, all of which revolutionized their lives. In exchange, the indigenous traders had to provide the Europeans with something they had in abundance — beaver pelts — and did not particularly need.

An important feature of the trade in beaver pelts was that they were most highly valued after they had been treated with natural oils and the long and rough guard-hairs had been removed. The most effective way to do this in pre-industrial society was to wear the pelts or to sleep in them. In short, what the Europeans wanted most of all was used pelts: those that had become a shiny black by being slept on or draped across a sweaty human body. Small wonder that the Aboriginal traders thought they were on to a good thing: from their perspective this was new money for old rope, as the saying goes.

There were, to be sure, drawbacks to the fur trade for the Aboriginal people, liabilities that would have been noticed even in the early stages. Their everyday lives were easier, but this change hampered their original way of life and some modification of culture occurred. The Aboriginal people began to depend on European goods in particular and some individuals and communities lost sight of their original ways of life before the arrival of metal goods. The location of flint or obsidian quarries for arrowheads became less important; the ability to chip a rock into a usable projectile point also disappeared. As Maritime peoples sacrificed more and more of their time on the seashore in order to pursue fur-bearing animals or trade partners farther inland, they came to rely on the French for foodstuffs. Increasingly, too, alcohol entered the trade equation and elicited a highly disruptive change.

Trade School

Historians in the 20th century debated whether Aboriginal motivations in the fur trade had been misunderstood. Generations assumed that a profit motive lay behind Aboriginal trade, one that fit nicely into European notions of classical economic theory. Over and over, however, the record revealed little price fluctuation: in the eastern woodlands at least, while there were price markups from trapper through middleman to the final Aboriginal trader, the price paid by the French was remarkably stable. This is explained by other historians as evidence of the importance of the social function of Aboriginal commerce. The act of trade was at least as significant as the quantity being traded. Nomadic peoples — even semi-nomadic peoples — have limited use for material goods and simply cannot accumulate riches in the way that sedentary societies might. Status, however, can be acquired through trade and through economic leadership; likewise a reliable and dependable source of goods has a value in itself. Every Euro-Canadian trader’s journal describes in some detail the elaborate gift-giving, speaking, and welcoming rituals that preceded trade. Days could pass between the meeting of the trade partners and the actual beginning of trade. Although some of the Aboriginal speeches announced expectations that quality goods in fair quantity would be exchanged for pelts, at the heart of these protocols was the relationship itself. Some historians have countered that, in some regions like the Subarctic and the West, stable prices disguise increased demands in other areas by Aboriginal traders: in their own specific context Aboriginal merchants were driving up their profits by squeezing other Aboriginal traders. Still other historians have responded with a critique that focuses on the alienation of Aboriginal production from Aboriginal control. Once dependency set in, it didn’t matter that the Aboriginal traders/communities weren’t employees of the trading companies: they had become a colonized working class anyway. When we see Aboriginal traders entering into commerce with Europeans from the 15th to the 20th centuries, then, it is important to be aware that the worth of the fur trade might be measured differently in each culture and context. As might success.[2]

It is hardly surprising to find that some Aboriginal groups became competitive and jealous of one another’s accomplishments in the trade. Once again, keeping in mind the smallness of the French settlements — only a few hundred people at best during most of the 17th century — Aboriginal traders saw them more as travelling merchants showing up with goods to sell, rather than as competition for resources. The goods that Aboriginal partners received, then, fit within the context of indigenous relations.

Champlain’s participation in the attack on Ticonderoga in 1609 and his continued support for trade with the Wendat excluded the Haudenosaunee from access to European goods, though not for long. The arrival of the Dutch in 1615 at the mouth of the Hudson River provided the Five Nations a strong commercial monopoly of their own. Their lands, however, lacked the fur resources open to Wendat traders’ partners farther north. Diverting that trade into their own hands was clearly a consideration when the Haudenosaunee launched raids against Wendat traders, travellers, and villages in the 1630s and 1640s. They were also recovering from the 1630s smallpox epidemic, which meant they were on the lookout for hostages who could be absorbed into Haudenosaunee society to replenish their numbers. These two strategies of aggression were to shape the Five Nations’ relations with the French. Having scattered the Wendat Confederacy in 1649, the League turned its attention to the destruction of Canada. The eradication of the French trading presence would force the fur trade from the north into Haudenosaunee hands and they would hold a monopoly as middlemen to the Dutch.

For some Aboriginal peoples, there was no going back. For others, there was no reason to do so. So long as trade survived so did the new technological paradigm.

Miscegnation

Colonial societies often exhibit a badly tilted imbalance between the number of men and women. This was the case in early New France, on the western fur trade frontier, and in British Columbia from the 1840s through the 1930s. Under these circumstances it was inevitable that newcomer males — though not Catholic priests — would look to the Aboriginal population for sexual and marriage partners.

Interracial sexual relations (or miscegnation) between Europeans and Aboriginal peoples occurred from the earliest days of New France and Newfoundland. The record suggests, not surprisingly, that these weren’t always consensual. More permanent heterosexual alliances, however, did not take long to appear. These were enabled by Aboriginal cultural practices that included polygyny. As well, Aboriginal men were, in some settings, comfortable with the idea of sharing their wife with newcomers, a practice that can be situated within the context of gift-giving diplomacy and the building of alliances. Aboriginal women, too, were not without power in building these relationships and recognized the value of both sex and the adoption of an outsider into the family through marriage. Divorce, in Aboriginal societies, was generally widely accepted and an easy thing to conclude. This gave women some ability to walk away (in some instances, literally) from a bad pairing.

As indicated above, demographic conditions among the Europeans abetted miscegnation. This was also sometimes the case among Aboriginal populations, as occurred in and around Montreal and in the outlying mission settlements of Mohawks in the late 17th and 18th centuries where there were more women than men. Conditions in some of the early mixed communities of Europeans and Aboriginals were generally poor. Disease continued to beat down Aboriginal numbers, which had psychological as well as physiological impacts. Cultural change was also underway: the Catholic priests were not necessarily receptive to the needs or motivations of women and, according to their creed, promoted a patriarchal model of relationships that robbed Aboriginal women of their traditional rights to divorce. As one historian has put it, “Women, still responsible for the heavy labour and often mistreated by husbands they could no longer divorce, began to despair. The need to love and procreate languished, along with the will to live, in these first generations torn between two worlds. ‘We rarely see the natives age,’ one governor remarked.”[3] Fertility and longevity, as this evidence suggests, suffered as did the women whose roles were being refashioned by others.

Farther inland, away from the intense oversight of the clergy in the St. Lawrence, Aboriginal-European relationships rapidly developed. Aboriginal communities treated these arrangements as confirmation of commercial and military alliances; Europeans, too, understood that they were more than convenient sexual liaisons. No Catholic priest would assent to a marriage in which one party was not Catholic, so these “marriages” were confirmed á là façon du pays (according to the custom of the country). And that façon or style was, of course, Aboriginal and, as one historian has said, it “converted trader strangers into relatives.”[4] These were Aboriginal protocols and expectations with which the Europeans would necessarily comply. If and when it came time for the French fur trader to return to Canada and/or France, this was taken in stride by Aboriginal cultures that were permissive of divorce and the end of relationships. Moreover, the matrilineal tendencies of Aboriginal cultures meant that any children arising from the relationship would be raised by their Aboriginal kin, so there was no question of childhood abandonment through divorce.

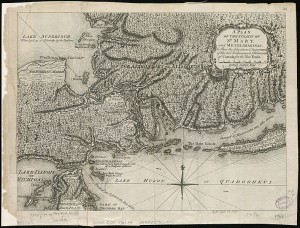

The challenge for Aboriginal peoples who viewed miscegnation as a means to secure resources, cooperation, and stability in their relationships with New France was the clergy. Missionaries were adamantly opposed to miscegnation and, of course, to any coupling outside of wedlock. They fulminated against Michilimackinac in particular, a hub of fur trade activity that they regarded as “a den of sin.”[5] In 1709 intermarriage was forbidden in the new fur trade centre of Fort Pontchartain du Détroit by order of the governor. These prohibitions were aimed first at the Euro-Canadian fur traders, but they had an impact on the Aboriginal partner community as well. Some Aboriginal women at Détroit and at the more Europeanized trading centres responded by accepting baptism from the clergy as a first step toward legitimizing the union. Their motivation was the rising fertility among Aboriginal women connected with fur trade society. Traditionally, the time between births was three or four years, but in mixed marriages the intervals were much shorter, no doubt due to both the expectations of the European partner and changes in diet and routine in fur trade post/fort society. The difference in birth rate was drastic; if a woman married at 18 in Aboriginal society, she might have four children by the time she turned 30; if she married a European, she might have as many as seven. Under the circumstances, a strategy of inclusion that involved accepting the sacraments from a missionary might serve to both protect the woman and preserve the status of her children within an increasingly blended fur trade society. (The experience of the children of these relationships is considered further in Chapter 8, Chapter 12, and Chapter 13.)

The effects of cultural adjustment were felt across most of North America by the early 18th century: wherever Aboriginal trading communities gathered in proximity to fur trade posts of the French (and, later, the Hudson’s Bay and North West Companies), the risks increased of exposure to disease and alcohol. The latter was heavily regulated and its sale was essentially illegal under the French regime, but it made its way into the trade equation anyhow. In every instance we see Aboriginal societies attempting to process the array of changes through well-established and largely effective cultural filters. Too many of the adjustments, however, came with a high cost. What appeared at first as opportunities consistent with familiar principles and goals too often became complicated and intractable.

Key Points

- Cultural and technological change among Aboriginal societies often took place in the proto-contact phase, before establishing direct relations with Europeans.

- Aboriginal participants in trade saw important advantages to trade with the newcomers and acted accordingly.

- The introduction of metal tools and some manufactured goods led to some advantages and liabilities as well.

- The terms and protocols of trade were set by Aboriginal participants and Europeans had to conform.

- Relationships between Europeans and Aboriginal peoples frequently took the form of marriages, most of which played a role in binding the newcomer trader to the Aboriginal woman’s family/clan/village.

Attributions

Figure 5.6

Algonquin Couple by Poisend-Ivy is in the public domain.

Figure 5.7

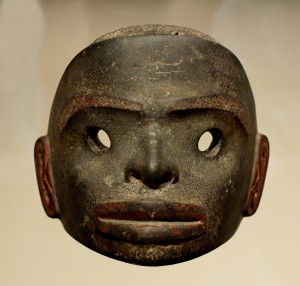

Nisgaa mask by Jastrow is in the public domain.

Figure 5.8

A plan of the Straits of St. Mary, and Michilimakinac by File Upload Bot (Magnus Manske) is used under a CC-BY 2.0 license.

- Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon in The Portable Karl Marx, ed. Eugene Kamenka (London: Penguin, 1983), 287. ↵

- For a thorough survey of this field, see Michael Payne, “Fur Trade Historiography: Past Conditions, Present Circumstances, and a Hint of Future Prospects,” From Rupert’s Land to Canada (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2001): 3-22. ↵

- Louise Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants in Seventeenth Century Montreal, trans. Liana Vardi (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1992), 7. ↵

- Jennifer S. H. Brown, "Children of the Early Fur Trades," in Childhood and Family in Canadian History, ed. Joy Parr (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1982), 45. ↵

- Ibid., 46. ↵