Chapter 8. Rupert’s Land and the Northern Plains, 1690-1870

8.6 Fur Trade Wars

The two companies found themselves increasingly in conflict in the West. NWC forts and trading posts glared across rivers at their HBC opposites, strange mirror images of Euro-Canadian commercial activity in a land dominated by Ojibwa and Cree. Competition between the English company and Montreal traders had been bloody since before the Conquest; the fact that they were both saluting the Union Jack after 1763 did little to ameliorate feelings. Moves were made in 1790 on the part of the NWC’s leadership to have Britain end the HBC monopoly, but that effort came to nothing.

The Montreal Factions

Relations within the NWC itself were hardly placid. The costs associated with long-distance transportation of goods and personnel to and from Montreal ate into profits. Tensions rose between the “winterers” and the agents, resulting in reorganizations and then, in response, breakaway partnerships such as the XY Company (a.k.a. the New North West Company). The 1790s and the first decade of the 19th century saw the Nor’Westers’ profitability and share of the fur supply rise while their unity fractured and healed. Their accomplishments in the West were hurried and impressive.

The pace had been set by people like Peter Pond (ca. 1740-1807), a bizarre and homicidal individual whose efforts in the West in the 1780s took him into the Athabasca system, a first for a non-Aboriginal and a seminal moment in the history of the NWC. A decade later (making good use of Pond’s maps) Alexander Mackenzie (1764-1820), another NWC agent, explored the river than now bears his name and then, four years later, he crossed the whole continent, emerging near the main village of the Nuxalk (Bella Coola). (Mackenzie was the first European to cross the continent; his accomplishment predates the American expedition of Lewis and Clark by a decade.)

The NWC subsequently sent out two other missions: one headed by Simon Fraser (1776-1862) in 1808 and the other by David Thompson (1770-1857) in 1811. In the process the company moved into what is now northern British Columbia, what Fraser called New Caledonia. A few years later they closed the loop by purchasing John Jacob Astor’s Fort Astoria in 1812, which transferred to the NWC the Pacific Fur Company’s (PFC) control of posts reaching as far north as Thompson Rivers Post (Fort Kamloops). This expansion on the part of the NWC carved a path running northwest from Lake of the Woods to the Mackenzie River, right across the southwesterly course of the HBC’s growth. Repeatedly the companies’ representatives would come to blows.

The Western Nations

This situation was not assisted by a change in Aboriginal attitudes toward trade. For peoples like the Chipewyan and the most northwestern of the Cree, having a trading post on their doorstep or even just somewhat nearer to their territory was an important advantage. Mackenzie reported that such groups normally travelled hundreds of miles to trade, journeys that took them away from their homelands, their hunting, and their other customary practices. They were, therefore, happy to encounter forthcoming traders who would “relieve them from such long, toilsome, and dangerous journies; and were immediately reconciled to give an advanced price for the articles necessary to their comfort and convenience.”[1]

Others were not so favourably impressed. The Niitsitapi and Grôs Ventres nursed a growing hostility toward the fur traders who were supplying their Cree adversaries with arms. Conflict broke out sporadically. Events in the cordillera region took a similar turn from 1795 when the Kutenai and Flathead (a.k.a. Salish) acquired guns from the NWC and American traders for use (successfully in 1810 and 1812) against their Piikuni (Piegan) enemies. The Piikuni thus joined the ranks of First Nations embittered against the newcomers. Even the Cree turned on the Euro-Canadians. In 1779 at Fort Montagne d’Aigle on the Saskatchewan River and again in 1781 at Fort des Trembles on the Assiniboine River, the Cree demonstrated their unwillingness to be cowed by arrogant traders.[2] The possibility arose in 1779-80 that the western Plains people — whose lands were increasingly saturated with fur traders of varying moral quality — would turn the newcomers out of the Plains entirely. Smallpox intervened in 1780 and further serious talk of a clearing of the West did not arise.

Conflict in the northwest was endemic after the fall of Wendake and the Beaver Wars, as Aboriginal peoples worked toward a readjustment of territory and resources. The 18th century witnessed British-American expansion into the trans-Appalachian west, causing further disruptions in traditional territories and invasions by displaced populations. Pressures were growing from all sides and they would not be relieved by landscape-scouring epidemics. Movement into new territories required adjustments and usually the occupants put up a fight. Some of the social and cultural changes that came with these movements and activities can only be described as revolutionary.

Key Points

- Montreal traders were setting the pace in the West and entering into direct competition with the HBC in Rupert’s Land, regardless of the latter’s monopoly.

- Political and social changes in the Western nations were manifest in changing attitudes toward the Europeans and Euro-Canadians.

Attributions

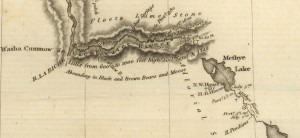

Figure 8.11

A journey from Prince of Wales’s Fort, in Hudson’s Bay, to the northern ocean : undertaken by order of the Hudson’s Bay Company for the discovery of copper mines, a north west passage, & c. in the years 1769, 1770, 1771 & 1772 by Samuel Hearne is in the public domain.

Figure 8.12

Franklin map fur route 3751971809 c0c67ca7d3 o huge map (2) by Kayoty is in the public domain.

- Barry M. Gough, “POND, PETER,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003). Accessed November 26, 2014, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/pond_peter_5E.html . ↵

- Olive Patricia Dickason, Canada’s First Nations: A History of Founding Peoples from Earliest Times, 3rd edition (Don Mills: OUP, 2002), 175-6. ↵