Chapter 10: Leading an Ethical Organization: Corporate Governance, Corporate Ethics, and Social Responsibility

Corporate Ethics and Social Responsibility

Learning Objectives

- Know the three levels and six stages of moral development suggested by Kohlberg.

- Describe famous corporate scandals.

- Understand how Bill 198 of 2002 provides a check on corporate ethical behaviour in Canada.

- Know the dimensions of corporate social performance tracked by KLD.

Stages of Moral Development

How do ethics evolve over time? Psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg suggests that there are six distinct stages of moral development and that some individuals move further along, or faster along, these stages than others (Kohlberg, 1981). Kohlberg’s six stages were grouped into three levels: (1) preconventional, (2) conventional, and (3) postconventional (Figure 10.5 “Stages of Moral Development”).

The preconventional level of moral reasoning is very egocentric in nature, and moral reasoning is tied to personal concerns. In stage 1, individuals focus on the direct consequences that their actions will have—for example, worry about punishment or getting caught. In stage 2, right or wrong is defined by the reward stage, where a “what’s in it for me” mentality is seen.

At this conventional level of moral reasoning, morality is principally judged by comparing individuals’ actions with the expectations of society. In stage 3, individuals are conformity driven and act with the goal of fulfilling social roles. Parents that encourage their children to be good boys and girls use this form of moral guidance. In stage 4, the importance of obeying laws, social conventions, or other forms of authority to aid in maintaining a functional society is encouraged. You might witness encouragement under this stage when using a cell phone in a restaurant or when someone is chatting too loudly in a library.

The postconventional level, or principled level, occurs when morality is more than simply following social rules or norms. Stage 5 considers different values and opinions. Thus laws are viewed as social contracts that promote the greatest good for the greatest number of people. Following democratic principles or voting to determine an outcome is common when this stage of reasoning is invoked. In stage 6, moral reasoning is based on universal ethical principles. For example, the golden rule that you should do unto others as you would have them do unto you illustrates one such ethical principle. At this stage, laws are grounded in the idea of right and wrong. Thus individuals follow laws because they are just and not simply because they will be punished if caught or shunned by society. Consequently, with this stage, the concept of civil disobedience emerges; that individuals have a duty to disobey unjust laws.

Corporate Scandals and Bill 198

In the 1990s and early 2000s, several corporate scandals were revealed in Canada that showed a lack of board vigilance, including Northern Telecom Limited, also known as Nortel. With the collapse of the Internet bubble, among other factors, Nortel stock price collapsed. Market capitalization of Nortel declined from $398 billion to less than $5 billion, and more than 60,000 people were laid off. John Roth, CEO and member of the Nortel board of directors, was criticized after it was revealed that he cashed in his own stock options for a personal gain of $135 million in 2000 alone.

In September 1991, Julian Assange of WikiLeaks was discovered in the act of hacking into the Melbourne master terminal of Nortel. In 2004, it was discovered that crackers (malicious hackers) gained almost complete access to Nortel’s systems. In spite of these findings, the breach was not properly addressed by the time the company started selling some of its assets in 2009. The Canadian federal government propped up Nortel with a $30 million loan, which outraged many Canadians who had already lost billions on Nortel on the stock market, yet would be asked for even more money to support Nortel through their taxes.

Financial irregularities were also discovered at Nortel’s Health and Welfare Trust (HWT), including a finding that $100 million was missing, and that a $37 million loan to Nortel had not been paid back. The HWT was an unregistered trust maintained by Nortel to provide medical, dental, life insurance, long-term disability, and survivor income and pension transition benefits. Until 2005, Nortel fully funded the disability insurance in its HWT. However, it is alleged that since then, the HWT breached their fiduciary duties to protect Nortel’s disabled employees and survivors of deceased employees by allowing Nortel to misdirect over $100 million from the HWT for purposes inconsistent with the terms of the HWT.

In the United States, perhaps the most famous corporate scandal involves Enron, an energy firm whose executive antics were documented in the film The Smartest Guys in the Room. Enron used accounting loopholes to hide billions of dollars in failed deals. When their scandal was discovered, top management cashed out millions in stock options while preventing lower-level employees from selling their stock. The collective acts of Enron led many employees to lose all their retirement holdings, and many Enron execs were sentenced to prison.

These were far from isolated incidents. Analysis shows that many of the warning signs were not acted on by boards, or worse, were covered up by auditors whose job it was to ensure accuracy in public financial reporting. Major audit firms were also found to be in conflict of interest positions, but offering various non-auditing services to the same firms they were under contract to audit. In response, the U.S. and Canadian governments passed sweeping new legislation with the hopes of restoring investor confidence while preventing future scandals. (See Figure 10.6 “Corporate Scandals.”) In the United States, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX), was passed in 2002, significantly changing how public companies reported their financial standings. (It was named after Democratic Senator Paul Sarbanes and Republican Representative Michael Oxley, the sponsors of the bill.) The new approach greatly benefited shareholders and stock investors by bolstering transparency in fiscal reporting. In Canada, Ontario’s Bill 198 was an omnibus bill that contained several far-reaching reforms regarding governance of publicly traded firms in Canada.

When Ontario passed Bill 198 in 2003, it essentially accomplished the same thing as SOX—in fact, it’s frequently referred to as the Canadian SOX (C-SOX). This bill came out as a result of corporate scandals that shook investor confidence. It increased scrutiny of corporate governance amid growing concern about auditor independence and the disclosure of internal controls over financial reporting, notes a PricewaterhouseCoopers report (2004).

The Ontario government introduced a piece of legislation called Keeping the Promise for a Strong Economy Act, and it was approved in 2002. Since Toronto is Canada’s largest stock market, this provincial legislation affected basically every Canadian company as well as every stock traded in Canada. In reality, the bill dealt broadly with a number of different government operation procedures and only a small part dealt with financial reporting.

The changes that encouraged the creation of Sarbanes-Oxley Act were so sweeping that comedian Jon Stewart quipped, “Did Wall Street have any rules before this? Can you just shoot a guy for looking at you wrong?” Despite the considerable merits of Sarbanes-Oxley, no legislation can provide a cure-all for corporate scandal (Figure 10.7 “Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX)”). As evidence, the scandal by Bernard Madoff that broke in 2008 represented the largest investor fraud ever committed by an individual, estimated to be approximately $64.5 billion. But in contrast to some previous scandals that resulted in relatively minor punishments for their perpetrators, Madoff was sentenced to 150 years in prison.

Measuring Corporate Social Performance

Kicking Horse Coffee’s and Oliberté Shoes’ commitment to fair trade offerings illustrates the concept of social entrepreneurship, in which a business is created with a goal of bettering both business and society (Schectman, 2010). Firms such as Oliberté exemplify a desire to improve corporate social performance (CSP). The degree to which a firm’s actions honor ethical values that respect individuals, communities, and the natural environment.[/footnote] in which a commitment to individuals, communities, and the natural environment is valued alongside the goal of creating economic value. Although determining the level of a firm’s social responsibility is subjective, this challenge has been addressed in detail by Kinder, Lydenberg and Domini & Co. (KLD), a Boston-based firm that rates firms on a number of stakeholder-related issues with the goal of measuring CSP. KLD conducts ongoing research on social, governance, and environmental performance metrics of publicly traded firms and reports such statistics to institutional investors. The KLD database provides ratings on numerous “strengths” and “concerns” for each firm along a number of dimensions associated with corporate social performance (Figure 10.8 “Measuring Corporate Social Performance”). The results of their assessment are used to develop the Domini social investments fund, which has performed at levels roughly equivalent to the S&P 500.

Assessing the community dimension of CSP is accomplished by assessing community strengths, such as charitable or innovative giving that supports housing, education, or relations with indigenous peoples, as well as charitable efforts worldwide, such as volunteer efforts or in-kind giving. A firm’s CSP rating is lowered when a firm is involved in tax controversies or other actions that negatively affect the community, such as plant closings, which can lower local property values.

For several years, Maclean’s magazine has partnered with Sustainalytics, a global leader in sustainability analysis, to select 50 leaders in corporate social responsibility—companies who know that doing good is just good business. Canada’s Top 50 Socially Responsible Companies are selected on the basis of their performance across a broad range of environmental, social, and governance indicators and rank at the top of their industry groups. In 2013, Bank of Montreal was chosen as the best in the banking category, partly based on these factors: (1) BMO’s board diversity policy ensures that women represent at least a third of the bank’s independent board of directors; (2) equity and debt financing to the renewable energy sector amounted to $3.6 billion in fiscal 2012, one of the highest among Canadian banks for that year; and (3) BMO funds a nationwide financial literacy program that aims to educate 45,000 students on personal finance over three years.

In the United States, the challenge of measuring CSP has been addressed in detail by Kinder, Lydenberg and Domini & Co. (KLD), a Boston-based firm that rates companies on a number of stakeholder-related issues with the goal of measuring CSP. KLD conducts ongoing research on social, governance, and environmental performance metrics of publicly traded firms and reports such statistics to institutional investors. The KLD database provides ratings on numerous “strengths” and “concerns” for each firm along a number of dimensions associated with corporate social performance.

CSP diversity strengths are scored positively by KLD when a company is known for promoting women and minorities, especially for board membership and the CEO position. Employment of the disabled and the presence of family benefits such as child or elder care would also result in a positive score. Diversity concerns include fines or civil penalties in conjunction with an affirmative action or other diversity-related controversy. Lack of representation by women on top management positions—suggesting that a glass ceiling is present at a company—would also negatively impact scoring on this dimension.

The employee relations dimension of CSP gauges potential strengths such as notable union relations, profit sharing and employee stock-option plans, favorable retirement benefits, and positive health and safety programs noted by Canadian occupational health and safety regulations. Employee relations concerns would be evident in poor union relations, as well as fines paid due to violations of health and safety standards. Substantial workforce reductions as well as concerns about adequate funding of pension plans also warrant concern for this dimension.

The environmental dimension records strengths by examining engagement in recycling, preventing pollution, or using alternative energies. KLD would also score a firm positively if profits derived from environmental products or services were a part of the company’s business. Environmental concerns such as penalties for hazardous waste, air, water, or other violations or actions such as the production of goods or services that could negatively impact the environment would reduce a firm’s CSP score.

Product quality/safety strengths exist when a firm has an established and/or recognized quality program; product quality safety concerns are evident when fines related to product quality and/or safety have been discovered or when a firm has been engaged in questionable marketing practices or paid fines related to antitrust practices or price fixing.

Corporate governance strengths are evident when lower levels of compensation for top management and board members exist, or when the firm owns considerable interest in another company rated favorably by KLD; corporate governance concerns arise when executive compensation is high or when controversies related to accounting, transparency, or political accountability exist.

Strategy at the Movies

Thank You for Smoking

Does smoking cigarettes cause lung cancer? Not necessarily, according to a fictitious lobbying group called the Academy of Tobacco Studies (ATS) depicted in Thank You for Smoking (2005), based on Christopher Buckley’s acclaimed 1994 novel of the same title. The ATS’s ability to rebuff the critics of smoking was provided by a three-headed monster of disinformation: scientist Erhardt Von Grupten Mundt who had been able to delay finding conclusive evidence of the harms of tobacco for thirty years, lawyers drafted from Ivy League institutions to fight against tobacco legislation, and a spin control division led by the smooth-talking Nick Naylor.

The ATS was a promotional powerhouse. In just one week, the ATS and its spin doctor Naylor distracted the American public by proposing a $50 million campaign against teen smoking, brokered a deal with a major motion picture producer to feature actors and actresses smoking after sex, and bribed a cancer-stricken advertising spokesman to keep quiet. But after the ATS’s transgressions were revealed and cigarette companies were forced to settle a long-standing class-action lawsuit for $246 billion, the ATS was shut down. Although few organizations promote a product as harmful as cigarettes, the lessons offered in Thank You for Smoking have wide application. In particular, the film highlights that choosing between ethical and unethical business practices is not only a moral issue, but it can also determine whether an organization prospers or dies.

Key Takeaways

- The work of Lawrence Kohlberg examines how individuals can progress in their stages of moral development. Lack of such development by many CEOs led to a number of scandals, as well as legislation such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 and C-SOX of 2003 that were enacted with the hope of deterring scandalous behaviour in the future. Firms such as KLD provide objective measures of both positive and negative actions related to corporate social performance.

Exercises

- How would your college or university fare if rated on the dimensions used by KLD?

- Do you believe that executives will become more ethical after legislation such as C-SOX?

References

Kohlberg, L. (1981). Essays in moral development: Vol. 1. The philosophy of moral development. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

PricewaterhouseCoopers. (2004). Bill 198-Overview. Retrieved from http://www.pwc.com/en_CA/ca/audit-assurance/publications/bill-198-0904-en.pdf

Rogers Media. (2014). Canada’s top 50 social responsibility programs. Retrieved from http://www.macleans.ca/canada-top-50-socially-responsible-corporations-2013/

Schectman, J. (2010). Good business. Newsweek, 156, 50.

Taylor, S. (2012, May 14). What C-SOX Means for Canadian Companies. Resolver Inc. Retrieved from http://www.resolvergrc.com/blog/internal-control-news/what-c-sox-means-for-canadian-companies/

Wikipedia Organization. (2014). Nortel. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nortel#Criticism_and_controversy

Image descriptions

Figure 10.5 image description: Stages of Moral Development

Psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg theorized that a person’s moral reasoning (which drives ethical behaviour) has six identifiable stages spread across three levels. Each successive stage is superior to the previous stage with regard to responding to moral dilemmas. We illustrate each stage below.

- Level 1 (Preconventional level). Here moral reasoning is closely tied to personal concerns,

- Stage 1. Obedience and punishment orientation (“how can I avoid punishment?”) An individual’s motivation to behave ethically is driven by the fear of getting caught and punishment.

- Stage 2. Self-interest (“what is in it for me?”) Right or wrong us a function of rewards in this stage, where a “you scratch my back and I’ll scratch your” mentality dominates.

- Level 2 (Conventional Level). Here moral reasoning is closely tied to personal concerns.

- Stage 3. Interpersonal accord and harmony. Individuals act with the goal of fulfilling social roles, such as student, parent, and worker.

- Stage 4. Authority and social order – maintaining orientation. The desire to maintain a functional society by obeying laws and drives behaviours.

- Level 3 (Postconventional level). Here moral reasoning is closely tied to personal ethics.

- Stage 5. Social contract orientation. Laws are viewed as social contracts that promote the greatest number of people. Upjust laws and policies must therefore be resisted.

- Stage 6. Universal ethical principles. Moral reasoning is based on universal ethical principles such as the “golden rule” that you should treat others as you would want them to treat you.

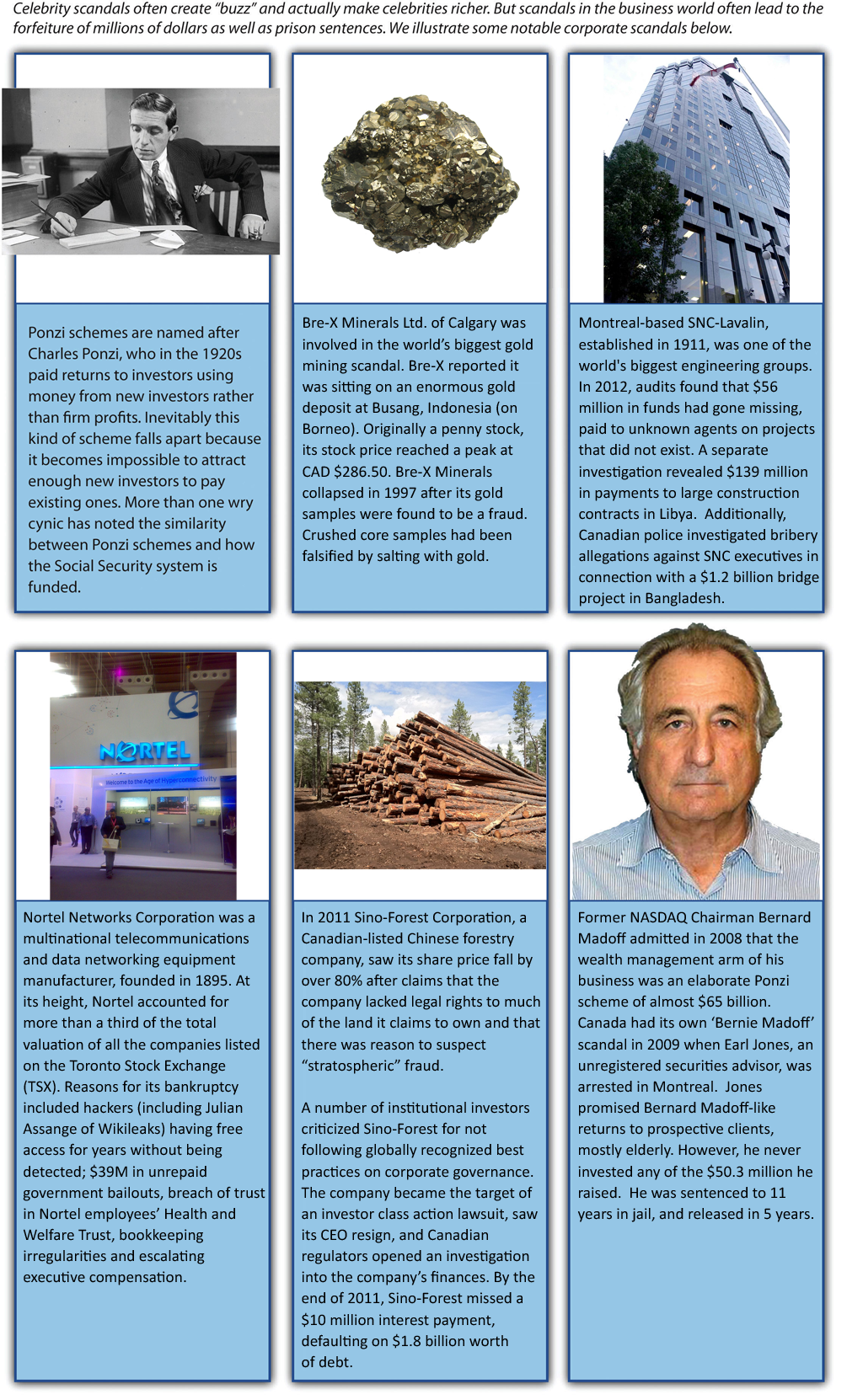

Figure 10.6 image description: Corporate Scandals

- Ponzi schemes are named after Charles ponzi, who in the 1920s paid returns to investors using money from new investors rather than firm profits. Inevitably this kind of scheme falls apart because it becomes impossible to attract enough new investors to pay existing ones. More than one wry cynic has noted the similarity between Ponzi schemes and how the Social Security system is funded.

- Bre-X Minerals Ltd. of Calgary was involved in the world’s biggest gold mining scandal. Bre-X reported it was sitting on an enormous gold deposit at Busang, Indonesia (on Borneo). Originally a penny stock, its stock price reached a peak at CAD $286.50. are-x Minerals collapsed in 1997 after its gold samples were found to be a fraud. Crushed core samples had been falsified by salting with gold.

- Montreal-based SNC-Lavalin, established in 1911, was one of the world’s biggest engineering groups. In 2012, audits found that $56 million in funds had gone missing, paid to unknown agents on projects that did not exist. A separate investigation revealed $139 million in payments to large construction contracts in Libya. Additionally, Canadian police investigated bribery allegations against SNC executves in connection with a $1.2 billion bridge project in Bangladesh.

- Nortel Networks Corporation was a multinational telecommunications and data networking equipment manufacturer, founded in 1895. At its height, Nortel accounted for

more than a third of the total valuation of all the companies listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX). Reasons for its bankruptcy included hackers (including Julian A55ange of Wikileaks) having free access for years Without being detected; 539M in unrepaid government bailouts, breach of trust in Nortel employees’ Health and Welfare Trust, bookkeeping irregularities and escalating executive compensation. - In 2011 Sino-Forest Corporation, a Canadian-listed Chinese forestry company, saw its share price fall by over 80% after claims that the company lacked legal rights to much of the land it claims to own and that there was reason to suspect “stratospheric” fraud. A number of institutional investors criticized Sino-Forest for not following globally recognized best practices on corporate governance. The company became the target of an investor class action lawsuit, saw its CEO resign, and Canadian regulators opened an investigation into the company’s finances. By the end of 2011, Sinc»Forest missed a $10 million interest payment, defaulting on $1.8 billion worth Of debt.Former NASDAQ

- Chairman Bernard Madoff admitted in 2008 that the wealth management arm of his business was an elaborate Ponzi scheme of almost $65 billion. Canada had its own ‘Bernie Madoff’ scandal in 2009 when Earl Jones, an unregistered securities advisor, was arrested in Montreal. Jones promised Bernard Madoff-like returns to prospective clients, mostly elderly. However, he never invested any of the $50.3 million he raised. He was sentenced to Il years in jail, and released in 5 years.

Figure 10.7 image description: Bill 192 and C-SOX

In the early 2000s, highly publicized fraud at Nortel. Enon and other large international firms revealed significant issues including conflicts of interest by auditors and securities analysts, boardroom failures, and inadequate funding of securities scrutiny. USA passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX), followed by Canada’s similar regulatory reforms, sometimes called C-SOX.

- The Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) was passed in the USA to restore investor confidence in corporate financial behaviour and reporting. As a result of SOX, officers and directors are held liable for accounting misreporting and malfeasance in both criminal and civil courts.

- SOX rules were designed to address the agency problems that resulted in massive fraud, misuse and expropriation of company funds. SOX provisions are aimed at improving auditor independence and accuracy of financial reports as well as addressing analyst conflicts of interest.

- Integration of the Canadian and U.S. capital markets along with the pressure to reform corporate governance and increase investor confidence in financial reports resulted in similar regulatory reforms in Canada, known as C-SOX.

- Amendments to the Ontario Securities Act (OSA) resulted in regulation and rules similar to those of SOX. The Ontario Legislature matched several provisions of SOX through amendments to the Ontario Securities Act via the Ontario Budget Measures Act (Bill 198).

- Rules and regulations concerning all provinces and jurisdictions of Canada are made through the Canadian Securities AdminIstrators (CSA). Canadian firms are unique due to the Multi-Jurisdictional Securities Disclosure System (MJDS), where each province controls many aspects of investing.

- One difference between U.S. and Canadian jurisdiction is that Canadian firms are allowed to list their common shares directly onU.S. exchanges whereas most other firms use ADRs (American depositary receipts).

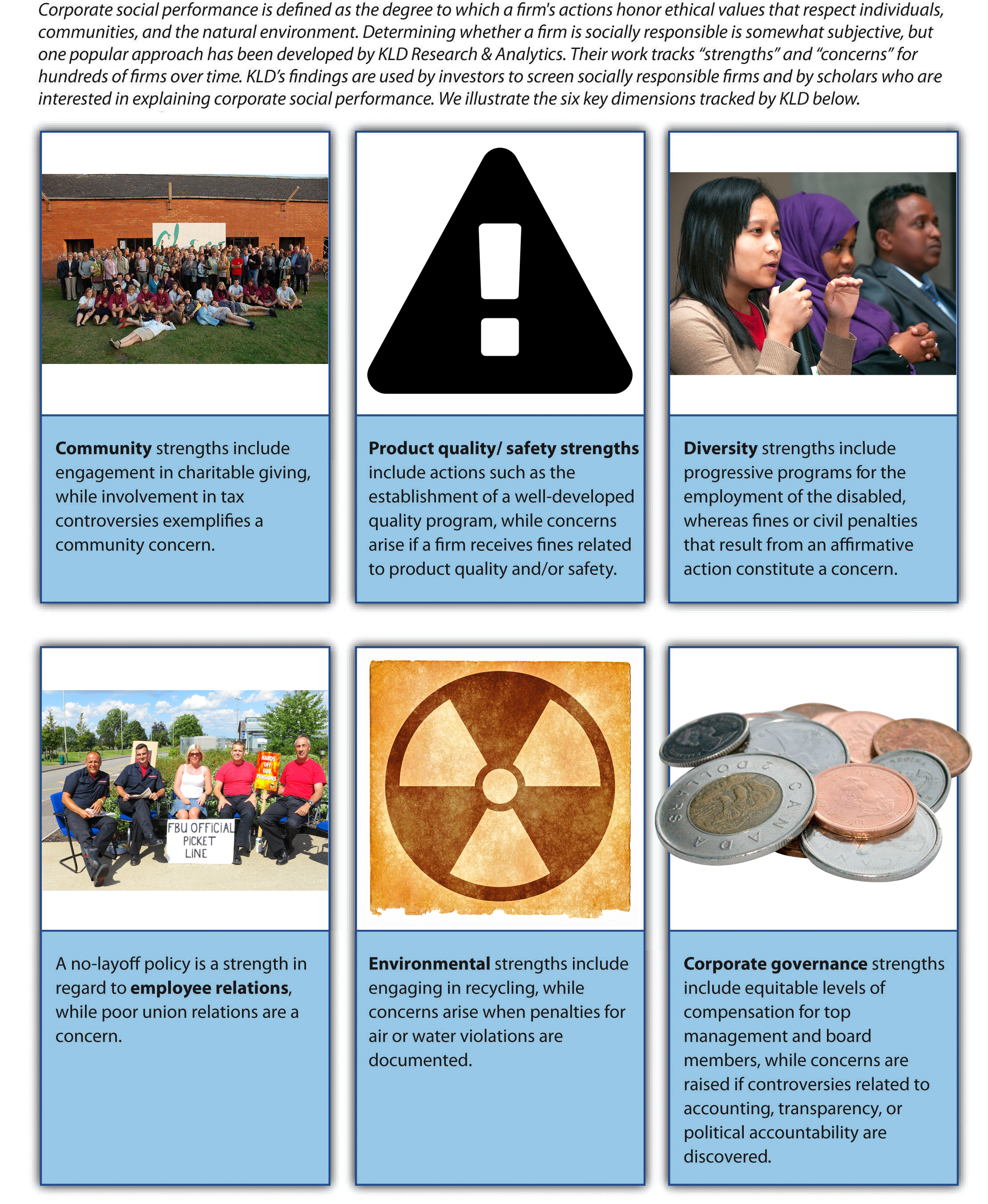

Figure 10.8 image description: Measure Corporate Social Performance

- Corporate social performance is defined as the degree to which a firm’s actions honor ethical values that respect individuals, communities, and the natural environment. Determining whether a firm is socially responsible is somewhat subjective, but one popular approach has been developed KLD Research & Analytics. Their work tracks “strengths” and “concerns” for hundreds of firms over time. KLD’s findings are used by investors to screen socially responsible firms and by scholars who are interested in explaining corporate social performance. We illustrate the six key dimensions tracked by KLD below.

- Community Strength include engagement in charitable giving, while involvement in tax controversies exemplifies a community concerns.

- Product quality/safety strengths include actions such as the establishment of a well-developed quality program, while concerns arise if a firm receives fines related to product quality and/or safety.

- Diversity strengths include progressive programs for the employment of the disabled, whereas fines or civil penalties that result from an affirmative action constitute a concern.

- A no-layoff policy is a strength in regard to employee relations, while poor union relations are a concern.

- Environmental strength include engaging in recycling, while concerns arise when penalties for air or water violations are documented.

- Corporate governance strengths include equitable levels of compensation for top management and board members, while concerns are raised if controversies related to accounting, transparency, or political accountability are discovered.

Media Attributions

- Figure 10.5: Attribution information for all included images is in the chapter conclusion.

- Figure 10.6: Attribution information for all included images is in the chapter conclusion.

- Figure 10.7: Attribution information for all included images is in the chapter conclusion.

- Figure 10.8: Attribution information for all included images is in the chapter conclusion.

- Bank of Montreal Sainte-Catherine-and-Cote-des-Neiges branch © Eastmain is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- CIGARETTE © Fried Dough is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

A proposed law that covers a number of diverse or unrelated topics.

Entrepreneurial actions where both economic and social value creation occur.

The degree to which a firm’s actions honor ethical values that respect individuals, communities, and the natural environment.