Chapter 5: Selecting Business-Level Strategy

Understanding Business-Level Strategy through “Generic Strategies”

Learning Objectives

- Understand the four primary generic strategies.

- Know the two dimensions that are critical to defining business-level strategy.

- Know the limitations of generic strategies.

Why Examine Generic Strategies?

Business-level strategy addresses the question of how a firm will compete in a particular industry (Figure 5.2 “Business-Level Strategies”). This seems to be a simple question on the surface, but it is actually quite complex. The reason is that there are a great many possible answers to this question. Consider, for example, the restaurants in your town or city. Chances are that you live fairly close to some combination of McDonald’s, Earls, Boston Pizza, The Keg, and dozens of other national chains, and a variety of locally based eateries that have just one location. Each of these restaurants competes using a business model that is at least somewhat unique. When an executive in the restaurant industry analyzes her company and her rivals, she needs to avoid getting distracted by all the nuances of different firm’s business-level strategies and losing sight of the big picture.

One solution is to think about business-level strategy in terms of generic strategies. A generic strategy is a general way of positioning a firm within an industry. Focusing on one generic strategy allows executives to concentrate on the core elements of firms’ business-level strategies and avoid competing in the markets better served by other generic strategies. The most popular set of generic strategies is based on the work of Professor Michael Porter of the Harvard Business School and subsequent researchers that have built on Porter’s initial ideas (Porter, 1980).

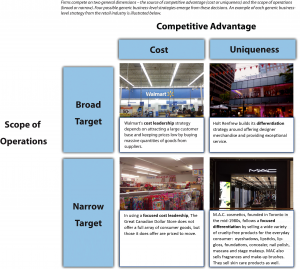

According to Porter, two competitive dimensions are the keys to business-level strategy. The first dimension is a firm’s source of competitive advantage: whether a firm seeks to gain an edge on rivals by keeping costs down or by offering something unique in the market. The second dimension is a firm’s scope of operations: whether a firm tries to target customers in general or seeks to attract just a segment of customers. Four generic business-level strategies emerge from these decisions: (1) cost leadership, (2) differentiation, (3) focused cost leadership, and (4) focused differentiation. In rare cases, firms are able to offer both low prices and unique features that customers find desirable. These firms are following a best-cost strategy. Firms that are not able to offer low prices or appealing unique features are referred to as “stuck in the middle,” where competition is greatest.

Understanding the differences that underlie generic strategies is important because different generic strategies offer considerably different value propositions to customers. A firm focusing on cost leadership will have a different value-chain configuration than a firm whose strategy focuses on differentiation. For example, marketing and sales for a differentiation strategy often requires extensive effort while some firms that follow cost leadership such as Denny’s are successful with limited marketing efforts. This chapter presents each generic strategy and the “recipe” generally associated with success when using that strategy. When firms follow these recipes, the result can be a strategy that leads to superior performance. But when firms fail to follow logical actions associated with each strategy, the result may be a value proposition configuration that is expensive to implement and does not satisfy enough customers to be viable.

Limitations of Generic Strategies

Examining business-level strategy in terms of generic strategies has limitations. Firms that follow a particular generic strategy tend to share certain features. For example, one way that cost leaders generally keep costs low is by not spending much on advertising. Not every cost leader, however, follows this path. While cost leaders such as Smitty’s Restaurants spend very little on advertising, Walmart spends considerable money on print and television advertising despite following a cost leadership strategy. Thus, a firm may not match every characteristic that its generic strategy entails. Indeed, depending on the nature of a firm’s industry, tweaking the recipe of a generic strategy may be essential to cooking up success.

Key Takeaways

- Business-level strategies examine how firms compete in a given industry. Firms derive such strategies by executives making decisions about whether their source of competitive advantage is based on price or differentiation and whether their scope of operations targets a broad or narrow market.

Exercises

- What are examples of each generic business-level strategy in the apparel industry?

- What are the limitations of examining firms in terms of generic strategies?

- Create a new framework to examine generic strategies using different dimensions than the two offered by Porter’s framework. What does your approach offer that Porter’s does not?

References

Porter, M. E. 1980. Competitive strategy: Techniques for analyzing industries and competitors. New York, NY: Free Press; Williamson, P. J., & Zeng, M. 2009. Value-for-money strategies for recessionary times. Harvard Business Review, 87(3), 66–74.

Image descriptions

Figure 5.2 image description: Business-Level Strategies

Firms compete on two general dimensions – the source of competitive advantage (cost or uniqueness) and the scope of operations (broad or narrow). Four possible generic business-level strategies emerge from these decisions. An example of each generic business-level strategy from the retail industry is illustrated below.

- Broad target and advantage in cost: Walmart’s cost leadership strategy depends on attracting a large customer base and keeping prices low by buying massive quantities of goods from suppliers.

- Board target and advantage in uniqueness: Holt Renfrew builds its differentiation strategy around offering designer merchandise and providing exceptional service.

- Narrow target and advantage in cost: In using a focused cost leadership, The Great Canadian Dollar Store does not offer a full array of consumer goods, but those it does offer are priced to move.

- Narrow target and advantage in uniqueness: M.A.C. cosmetics, founded in Toronto in the mid-1980s, follows a focused differentiation by selling a wide variety of cruelty-free products for the everyday consumer: eyeshadows, lipsticks, lip gloss, foundations, concealer, nail polish, mascara and stage makeup. MAC also sells fragrances and make-up brushes. They sell skin care products as well.