Chapter 9: Executing Strategy through Organizational Design

Creating Organizational Control Systems

Learning Objectives

- Understand the three types of control systems.

- Know the strengths and weaknesses of common management fads.

In addition to creating an appropriate organizational structure, effectively executing strategy depends on the skillful use of organizational control systems. Executives create strategies to try to achieve their organization’s vision, mission, and goals. Organizational control systems allow executives to track how well the organization is performing, identify areas of concern, and then take action to address the concerns. Three basic types of control systems are available to executives: (1) output control, (2) behavioural control, and (3) clan control. Different organizations emphasize different types of control, but most organizations use a mix of all three types.

Output Control

Output control focuses on measurable results within an organization. Examples from the business world include the number of hits a website receives per day, the number of microwave ovens an assembly line produces per week, and the number of vehicles a car salesperson sells per month (Figure 9.16 “Output Controls”). In each of these cases, executives must decide what level of performance is acceptable, communicate expectations to the relevant employees, track whether performance meets expectations, and then make any needed changes. In an ironic example, a group of post office workers in Pensacola, Florida, were once disappointed to learn that their paychecks had been lost—by the U.S. Postal Service! The corrective action was simple: they started receiving their pay via direct deposit rather than through the mail.

Many times the stakes are much higher. In early 2011, Delta Air Lines was forced to face some facts as part of its use of output control. Data gathered by the federal government revealed that only 77.4 percent of Delta’s flights had arrived on time during 2010. This performance led Delta to rank dead last among the major U.S. airlines and fifteenth out of eighteen total carriers (Yamanouchi, 2011). In response, Delta took important corrective steps. In particular, the airline added to its ability to service airplanes and provided more customer service training for its employees. Because some delays are inevitable, Delta also announced plans to staff a Twitter account called Delta Assist around the clock to help passengers whose flights are delayed. These changes and others paid off. For the second quarter of 2011, Delta enjoyed a $198 million profit, despite having to absorb a $1 billion increase in its fuel costs due to rising prices (Yamanouchi, 2011).

Output control also plays a big part in the university experience. For example, test scores and grade point averages are good examples of output measures. If you perform badly on a test, you might take corrective action by studying harder or by studying in a group for the next test. At colleges and universities, students may be put on academic probation when their grades or grade point average drops below a certain level. If their performance does not improve, they may be removed from their major and even suspended from further studies. On the positive side, output measures can trigger rewards too. A very high grade point average can lead to placement on the dean’s list and graduating with honors.

Arthur Erickson, noted Canadian architect, graduated from University of British Columbia and was commissioned to design the Museum of Anthropology there, which opened in 1976. It was inspired by the post-and-beam architecture of northern Northwest Coast First Nations people.

Behavioural Control

While output control focuses on results, behavioural control focuses on controlling the actions that ultimately lead to results. In particular, various rules and procedures are used to standardize or to dictate behaviour (Figure 9.18 “Behavioural Controls”). In most states, for example, signs are posted in restaurant bathrooms reminding employees that they must wash their hands before returning to work. The dress codes that are enforced within many organizations are another example of behavioural control. To try to prevent employee theft, many firms have a rule that requires checks to be signed by two people. Some employers may prefer non-smoking employees, as cigarette breaks can take as much as 40 minutes out of a workday, plus higher absenteeism and associated health costs for smokers.

Output control also plays a significant role in the university experience. An illustrative (although perhaps unpleasant) example is penalizing students for not attending class. Professors grade attendance to dictate students’ behaviour; specifically, to force students to attend class. Meanwhile, if you were to suggest that a rule should be created to force professors to update their lectures at least once every five years, we would not disagree with you.

Outside the classroom, behavioural control is a major factor within university and college athletic programs. The Canadian Collegiate Athletic Association (CCAA) governs college athletics using a set of rules, policies, and procedures. CCAA members, all players, and coaches are expected to follow the standard guidelines and principles of the CCAA Code of Ethics, and failure to comply will result in disciplinary action. Some degree of behavioural control is needed within virtually all organizations.

Creating an effective reward structure is key to effectively managing behaviour because people tend to focus their efforts on the rewarded behaviours. Problems can arise when people are rewarded for behaviours that seem positive on the surface but that can actually undermine organizational goals under some circumstances. For example, restaurant servers are highly motivated to serve their tables quickly because doing so can increase their tips. But if a server devotes all his or her attention to providing fast service, other tasks that are vital to running a restaurant, such as communicating effectively with managers, host staff, chefs, and other servers, may suffer. Managers need to be aware of such trade-offs and strive to align rewards with behaviours. For example, wait staff who consistently behave as team players could be assigned to the most desirable and lucrative shifts, such as nights and weekends.

Clan Control

Instead of measuring results (as in outcome control) or dictating behaviour (as in behavioural control), clan control is an informal type of control. Specifically, clan control relies on shared traditions, expectations, values, and norms to lead people to work toward the good of their organization (Figure 9.20 “Clan Controls”). Clan control is often used heavily in settings where creativity is vital, such as many high-tech businesses. In these companies, output is tough to dictate, and many rules are not appropriate. The creativity of a research scientist would be likely to be stifled, for example, if he or she were given a quota of patents that must be met each year (output control) or if a strict dress code were enforced (behavioural control).

Google is a firm that relies on clan control to be successful. Employees are permitted to spend 20 percent of their work week on their own innovative projects. The company offers an ‘‘ideas mailing list’’ for employees to submit new ideas and to comment on others’ ideas. Google executives routinely make themselves available two to three times per week for employees to visit with them to present their ideas. These informal meetings have generated a number of innovations, including personalized home pages and Google News, which might otherwise have never been adopted.

Some executives look to clan control to improve the performance of struggling organizations. In 2014, Rogers Communications CEO Guy Laurence formally unveiled his plan to revitalize growth at the country’s largest communications firm. The strategy, dubbed “Rogers 3.0,” aimed to improve the customer experience and use the company’s assets—which include everything from magazines to the Toronto Blue Jays—together in a more effective way. Laurence explained the issues he believed the company struggles with, and how his plan will address them. The reorganization is aimed at focusing on better customer service by bringing together all of the elements of customer experience—10,400 staff—into a single unit reporting to him. In plans to improve customer service to business and enterprise customers, Rogers has split out consumers from enterprise users, believing there’s a growth story in enterprise. Finally, Laurence said that Rogers’ stable of sports, broadcast, and publishing properties would differentiate the company from its telecom peers and commented, “I believe content is the most important part of our mix” (Castaldo, 2014).

Clan control is also important in many Canadian cities. Vancouver has the steam clock and Wreck Beach; Toronto has the CN Tower and the Blue Jays; Edmonton has the Oilers and West Edmonton Mall. These attractions are sources of pride to residents and desired places to visit for tourists; they help people feel like they belong to something special.

It is worth noting that control systems, once embedded in an organization, become very difficult to change. Control systems emerged within an organization, not by accident, but in response to the firm’s need to monitor employees’ work to encourage high performance. Changing results metrics is an invitation for gaming the data with employees finding innovative ways to ensure that the data shows they are performing at the expected level, while behaviour and clan culture are notoriously difficult to change, often taking a decade or more to truly change. New senior executives often tweak control systems in an effort to improve performance. However, the time required to actually implement such changes often exceeds the executive’s tenure with the firm—thus the phrase, latest (management) fad.

Management Fads: Out of Control?

Don’t chase the latest management fads. The situation dictates which approach best accomplishes the team’s mission.

– Colin Powell, former U.S. Secretary of State

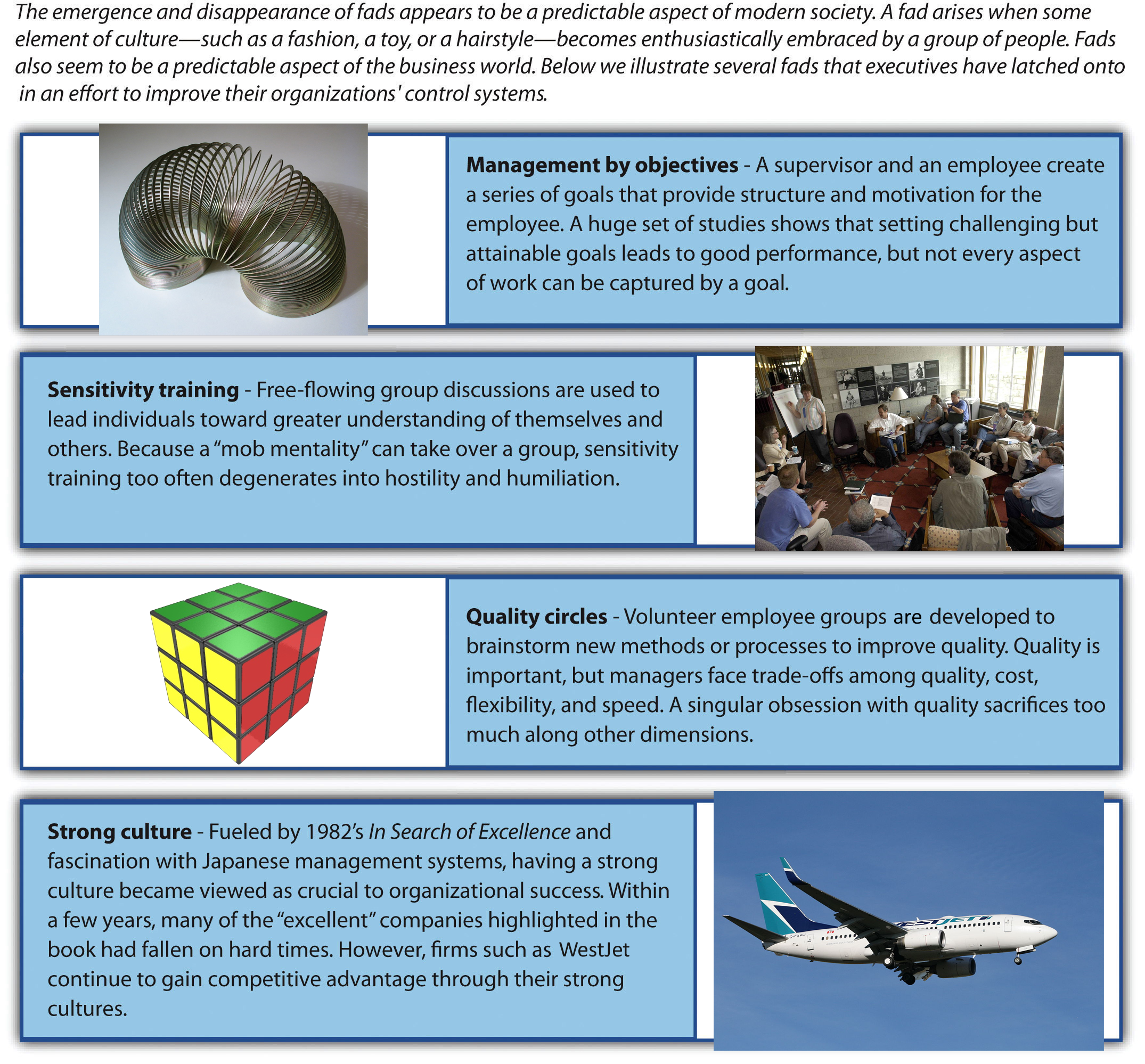

The emergence and disappearance of fads appears to be a predictable aspect of modern society. A fad arises when some element of popular culture becomes enthusiastically embraced by a group of people. Over the past few decades, for example, fashion fads have included leisure suits (1970s), “Members Only” jackets (1980s), Doc Martens shoes (1990s), and Crocs (2000s). Ironically, the reason a fad arises is also usually the cause of its demise. The uniqueness (or even outrageousness) of a fashion, toy, or hairstyle creates “buzz” and publicity but also ensures that its appeal is only temporary (Ketchen & Short, 2011).

Fads also seem to be a predictable aspect of the business world (Figure 9.22 “Managing Management Fads”). As with cultural fads, many provocative business ideas go through a life cycle of creating buzz, captivating a group of enthusiastic adherents, and then giving way to the next fad. Bookstore shelves offer a seemingly endless supply of popular management books whose premises range from the intriguing to the absurd. Within the topic of leadership, for example, various books promise to reveal the “leadership secrets” of an eclectic array of famous individuals such as Jesus Christ, Hillary Clinton, Attila the Hun, and Santa Claus.

Beyond the striking similarities between cultural and business fads, there are also important differences. Most cultural fads are harmless, and they rarely create any long-term problems for those that embrace them. In contrast, embracing business fads could lead executives to make bad decisions. As the quote from Colin Powell suggests, relying on sound business practices is much more likely to help executives to execute their organization’s strategy than are generic words of wisdom from Old St. Nick.

Many management fads have been closely tied to organizational control systems. For example, one of the best-known fads was an attempt to use output control to improve performance. Management by objectives (MBO) is a process wherein managers and employees work together to create goals. These goals guide employees’ behaviours and serve as the benchmarks for assessing their performance. Following the presentation of MBO in Peter Drucker’s 1954 book The Practice of Management, many executives embraced the process as a cure-all for organizational problems and challenges as if previous management had not been concerned with their objectives!

Like many fads, however, MBO became a good idea run amok. Companies that attempted to create an objective for every aspect of employees’ activities eventually discovered that this was unrealistic. The creation of explicit goals can conflict with activities involving tacit knowledge about the organization. Intangible notions such as “providing excellent customer service,” “treating people right,” and “going the extra mile” are central to many organizations’ success, but these notions are difficult if not impossible to quantify. Thus, in some cases, getting employees to embrace certain values and other aspects of clan control is more effective than MBO.

Quality circles were a second fad that built on the notion of behavioural control. Quality circles began in Japan in the 1960s and were first introduced in the United States in 1972. A quality circle is a formal group of employees that meets regularly to brainstorm solutions to organizational problems. As the name “quality circle” suggests, identifying behaviours that would improve the quality of products and the operations management processes that create the products was the formal charge of many quality circles.

While the quality circle fad depicted quality as the key driver of productivity, it quickly became apparent that this perspective was too narrow. Instead, quality is just one of four critical dimensions of the production process; speed, cost, and flexibility are also vital. Maximizing any one of these four dimensions often results in a product that simply cannot satisfy customers’ needs. Many products with perfect quality, for example, would be created too slowly and at too great a cost to compete in the market effectively. Thus trade-offs among quality, speed, cost, and flexibility are inevitable.

Improving clan control was the aim of sensitivity-training groups (or T-groups) that were used in many organizations in the 1960s. This fad involved gatherings of approximately eight to fifteen people openly discussing their emotions, feelings, beliefs, and biases about workplace issues. In stark contrast to the rigid nature of MBO, the T-group involved free-flowing conversations led by a facilitator. These discussions were thought to lead individuals to greater understanding of themselves and others. The anticipated results were more enlightened workers and a greater spirit of teamwork.

Research on social psychology has found that groups are often far crueler than individuals. Unfortunately, this meant that the candid nature of T-group discussions could easily degenerate into accusations and humiliation. Eventually, the T-group fad gave way to recognition that creating potentially hurtful situations has no place within an organization. Hints of the softer side of T-groups can still be observed in modern team-building fads, however. Perhaps the best known is the “trust game,” which claims to build trust between employees by having individuals fall backward and depend on their coworkers to catch them.

Improving clan control was the basis for the fascination with organizational culture that was all the rage in the 1980s. This fad was fueled by a best-selling 1982 book titled In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s Best-Run Companies. Authors Tom Peters and Robert Waterman studied companies that they viewed as stellar performers and distilled eight similarities that were shared across the companies. Most of the similarities, including staying “close to the customer” and “productivity through people,” arose from powerful corporate cultures. The book quickly became an international sensation; more than three million copies were sold in the first four years after its publication.

Soon it became clear that organizational culture’s importance was being exaggerated. Before long, both the popular press and academic research revealed that many of Peters and Waterman’s “excellent” companies quickly had fallen on hard times. Basic themes such as customer service and valuing one’s company are quite useful, but these clan control elements often cannot take the place of holding employees accountable for their performance.

The history of fads allows us to make certain predictions about today’s hot ideas, such as empowerment, “good to great,” and viral marketing. Executives who distill and act on basic lessons from these fads are likely to enjoy performance improvements. Empowerment, for example, builds on important research findings regarding employees—many workers have important insights to offer to their firms, and these workers become more engaged in their jobs when executives take their insights seriously. Relying too heavily on a fad, however, seldom turns out well.

Just as executives in the 1980s could not treat In Search of Excellence as a recipe for success, today’s executives should avoid treating James Collins’s 2001 best-selling book Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap…and Others Don’t as a detailed blueprint for running their companies. Overall, executives should understand that management fads usually contain a core truth that can help organizations improve but that a balance of output, behavioural , and clan control is needed within most organizations. As legendary author Jack Kerouac noted, “Great things are not accomplished by those who yield to trends and fads and popular opinion.”

Key Takeaways

- Organizational control systems are a vital aspect of executing strategy because they track performance and identify adjustments that need to be made. Output controls involve measurable results. Behavioural controls involve regulating activities rather than outcomes. Clan control relies on a set of shared values, expectations, traditions, and norms. Over time, a series of fads intended to improve organizational control processes have emerged. Although these fads tend to be seen as cure-alls initially, executives eventually realize that an array of sound business practices is needed to create effective organizational controls.

Exercises

- What type of control do you think works most effectively with you and why?

- What are some common business practices that you predict will be considered fads in the future?

- How could you integrate each type of control intro a college classroom to maximize student learning?

References

Adams, S. (2013, June 5). Every Smoker Costs An Employer $6,000 A Year. Really? Forbes. Retrieved from: http://www.forbes.com/sites/susanadams/2013/06/05/every-smoker-costs-an-employer-6000-a-year-really/

Castaldo, J. (2014, May 23). Rogers CEO Guy Laurence says sweeping restructuring is aimed at improving customer service. Canadian Business. Retrieved from http://www.canadianbusiness.com/companies-and-industries/guy-laurence-rogers-3/

Ketchen, D. J., & Short, J. C. (2011). Separating fads from facts: Lessons from “the good, the fad, and the ugly.” Business Horizons, 54, 17–22.

UBC Alumni Affairs. (2009, Fall). From Hugs to Hazing: A History of Student Orientation. Retrieved from http://www.alumni.ubc.ca/trekmagazine/25-fall2009/hazing.php

Wikipedia Organization. (2014). Museum of Anthropology at UBC. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Museum_of_Anthropology_at_UBC

Image description

Figure 9.16 image description: Output Controls

Outcome controls assess measurable production and other tangible results. Often output controls emphasize “bottom-line” performance. We illustrate some outcome controls found in organizations below.

- Because real estate agents are paid a percentage of the selling price when a house sells, the number of dollars generated in houses sold is an important metric. Many realty offices have designations like “five million dollar club”to recognize very productive realtors.

- Grade point averages provide a tangible means to compare students for employers and graduate schools.

- In the movie Elf, the main character Buddy leaves Santa’s workshop when the number of Etch-A-Sketch toys he produces is nearly nine hundred units lower than the standard pace.

- To earn tenure in a research-focused business schools, a professor’s output generally must include publishing numerous high-quality articles in reputable scholarly journals.

- Within restaurants, servers can increase a key output—amount of tips received—by providing customers with fast, friendly, and high-quality service.

Figure 9.18 image description: Behavioural Controls

Behavioural controls dictate the actions Of individuals. Such controls Often emphasize rules and procedures. We illustrate some behavioural controls found in organizations below.

- No shoes, no shirt, no paycheck. Many food service companies have strict attire requirements to ensure employees are in compliance with the rules of the company and the local health department.

- Casual Fridays provide a welcome break in offices that enforce strict dress codes.

- Many businesses require that checks are signed by two people. This prevents a dishonest employee from embezzling money.

- Grading attendance is a behavioural control designed to force students to show up for class. This can be very helpful because research shows that attendance is positively related to grades. Unfortunately, however, there are no behavioural controls that force professors’ lectures to be interesting.

- Need a puff? In Ontario, British Columbia, and many other provinces, legislation prohibits smoking in any enclosed public place or enclosed workplace, including restaurants, bars, and work vehicles. Some provinces prohibit designated smoking rooms (DSRs) in any enclosed public place or enclosed workplace. The Federal Government also has passed the Non-smokers’ Health Act.

Figure 9.20 image description: Clan Controls

Rather than measuring results (as in outcome control) or dictating behaviour (as in behavioural control), clan control relies on shared traditions, expectations, values, and norms to lead people to work toward the good of their organization. Some Of the most interesting and unusual examples of clan control are found on college campuses. Below we illustrate a few striking examples that help build school spirit and loyalty at the University of British Columbia.

- During “Frosh Week,” UBC around 1920, freshmen were subjected to various combinations of paint, dye, grease, foodstuffs, blindfolds, dunking, electric shocks, shaving, and messy or uncomfortable obstacle courses before being marched through the streets of Vancouver by older students beating pans and reciting Varsity chants and yells.

- In keeping with their well-earned reputation for rowdy intransigence in the 1950s, some UBC engineering students did their best to paint themselves as the “bad boys” on campus with spitting contests, homage to a symbolic Lady Godiva, sorties by goon squads during Frosh Week, and such childish pranks as stealing toilet seats or other campus fixtures.

- By the 1980s, some student pranks and stunts were losing their appeal. Although beer drinking contests and the occasional tanking still occurred each autumn, freshman hazing had effectively been discredited and discontinued; and instead of the near-riots of earlier years, inter-faculty rivalry found less damaging outlets, such as the symbolic vandalism of the new concrete “E” block placed on Main Mall.

Figure 9.22 image description: Managing Management Fads

The emergence and disappearance of fads appears to be a predictable aspect of modern society. A fad arises when some element of culture—such as a fashion, a toy, or a hairstyle—becomes enthusiastically embraced by a group of people. Fads also seem to be a predictable aspect of the business world. Below we illustrate several fads that executives have latched onto in an effort to improve their organizations ‘ control systems.

- Management by objectives – A supervisor and an employee create a series of goals that provide structure and motivation for the employee. A huge set of studies shows that setting challenging but attainable goals leads to good performance, but not every aspect of work can be captured by a goal.

- Sensitivity training – Free-flowing group discussions are used to lead individuals toward greater understanding of themselves and others. Because a “mob mentality” can take over a group, sensitivity training too often degenerates into hostility and humiliation.

- Quality circles – Volunteer employee groups are developed to brainstorm new methods or processes to improve quality. Quality is important, but managers face trade-offs among quality, cost, flexibility, and speed. A singular obsession with quality sacrifices too much along other dimensions.

- Strong culture – Fueled by 1 982’s In Search of Excellence and fascination with Japanese management systems, having a strong culture became viewed as crucial to organizational success. Within a few years, many of the “excellent” companies highlighted in the book had fallen on hard times. However, firms such as WestJet continue to gain competitive advantage through their strong cultures.

Media Attributions

- Figure 9.16: Attribution information for all included images is in the chapter conclusion.

- UBC Museum of Anthropology Building1 © Tim Gillin is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 9.18: Attribution information for all included images is in the chapter conclusion.

- Manhattan New York City 2009 PD 20091130 209 © Sterilgutassistentin is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 9.20: Attribution information for all included images is in the chapter conclusion.

- noogler © Tduk Alex Lozupone is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 9.22: Attribution information for all included images is in the chapter conclusion.

- Kickball © James is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

Allow executives to track how well the organization is performing, identify areas of concern, and then take action to address the concerns.

A focus on measurable results within an organization.

A focus on specifying the actions that ultimately lead to results.

Relying on shared traditions, expectations, values, and norms to lead people to work toward the good of their organization.

A process wherein managers and employees work together to create goals.

A formal group of employees that meet regularly to brainstorm solutions to organizational problems.

Groups of people that meet to discuss emotions, feelings, beliefs, and biases about workplace issues to gain greater understanding of themselves and others.

Values and norms embraced by an organization that determine how people interact with other organizational members as well as external stakeholders.