Chapter 13 Streams and Floods

13.3 Stream Erosion and Deposition

As we discussed in Chapter 6, flowing water is a very important mechanism for both erosion and deposition. Water flow in a stream is primarily related to the stream’s gradient, but it is also controlled by the geometry of the stream channel. As shown in Figure 13.14, water flow velocity is decreased by friction along the stream bed, so it is slowest at the bottom and edges and fastest near the surface and in the middle. In fact, the velocity just below the surface is typically a little higher than right at the surface because of friction between the water and the air. On a curved section of a stream, flow is fastest on the outside and slowest on the inside.

![Figure 13.14 The relative velocity of stream flow depending on whether the stream channel is straight or curved (left), and with respect to the water depth (right). [SE]](https://opentextbc.ca/geology/wp-content/uploads/sites/110/2016/07/meandering-300x110.png)

Other factors that affect stream-water velocity are the size of sediments on the stream bed — because large particles tend to slow the flow more than small ones — and the discharge, or volume of water passing a point in a unit of time (e.g., m3/second). During a flood, the water level always rises, so there is more cross-sectional area for the water to flow in; however, as long as a river remains confined to its channel, the velocity of the water flow also increases.

Figure 13.15 shows the nature of sediment transportation in a stream. Large particles rest on the bottom — bedload — and may only be moved during rapid flows under flood conditions. They can be moved by saltation (bouncing) and by traction (being pushed along by the force of the flow).

Smaller particles may rest on the bottom some of the time, where they can be moved by saltation and traction, but they can also be held in suspension in the flowing water, especially at higher velocities. As you know from intuition and from experience, streams that flow fast tend to be turbulent (flow paths are chaotic and the water surface appears rough) and the water may be muddy, while those that flow more slowly tend to have laminar flow (straight-line flow and a smooth water surface) and clear water. Turbulent flow is more effective than laminar flow at keeping sediments in suspension.

Stream water also has a dissolved load, which represents (on average) about 15% of the mass of material transported, and includes ions such as calcium (Ca+2) and chloride (Cl-) in solution. The solubility of these ions is not affected by flow velocity.

![Figure 13.15 Modes of transportation of sediments and dissolved ions (represented by red dots with + and – signs) in a stream. [SE]](https://opentextbc.ca/geology/wp-content/uploads/sites/110/2016/07/transportation-of-sediments.png)

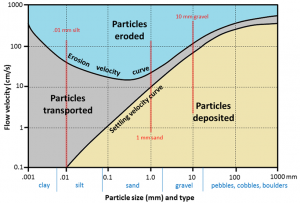

The faster the water is flowing, the larger the particles that can be kept in suspension and transported within the flowing water. However, as Swedish geographer Filip Hjulström discovered in the 1940s, the relationship between grain size and the likelihood of a grain being eroded, transported, or deposited is not as simple as one might imagine (Figure 13.16). Consider, for example, a 1 mm grain of sand. If it is resting on the bottom, it will remain there until the velocity is high enough to erode it, around 20 cm/s. But once it is in suspension, that same 1 mm particle will remain in suspension as long as the velocity doesn’t drop below 10 cm/s. For a 10 mm gravel grain, the velocity is 105 cm/s to be eroded from the bed but only 80 cm/s to remain in suspension.

On the other hand, a 0.01 mm silt particle only needs a velocity of 0.1 cm/s to remain in suspension, but requires 60 cm/s to be eroded. In other words, a tiny silt grain requires a greater velocity to be eroded than a grain of sand that is 100 times larger! For clay-sized particles, the discrepancy is even greater. In a stream, the most easily eroded particles are small sand grains between 0.2 mm and 0.5 mm. Anything smaller or larger requires a higher water velocity to be eroded and entrained in the flow. The main reason for this is that small particles, and especially the tiny grains of clay, have a strong tendency to stick together, and so are difficult to erode from the stream bed.

It is important to be aware that a stream can both erode and deposit sediments at the same time. At 100 cm/s, for example, silt, sand, and medium gravel will be eroded from the stream bed and transported in suspension, coarse gravel will be held in suspension, pebbles will be both transported and deposited, and cobbles and boulders will remain stationary on the stream bed.

Exercises

Exercise 13.3 Understanding the Hjulström-Sundborg Diagram

Refer to the Hjulström-Sundborg diagram (Figure 13.16) to answer these questions.

1. A fine sand grain (0.1 mm) is resting on the bottom of a stream bed.

(a) What stream velocity will it take to get that sand grain into suspension?

(b) Once the particle is in suspension, the velocity starts to drop. At what velocity will it finally come back to rest on the stream bed?

2. A stream is flowing at 10 cm/s (which means it takes 10 s to go 1 m, and that’s pretty slow).

(a) What size of particles can be eroded at 10 cm/s?

(b) What is the largest particle that, once already in suspension, will remain in suspension at 10 cm/s?

A stream typically reaches its greatest velocity when it is close to flooding over its banks. This is known as the bank-full stage, as shown in Figure 13.17. As soon as the flooding stream overtops its banks and occupies the wide area of its flood plain, the water has a much larger area to flow through and the velocity drops significantly. At this point, sediment that was being carried by the high-velocity water is deposited near the edge of the channel, forming a natural bank or levée.

![Figure 13.17 The development of natural levées during flooding of a stream. The sediments of the levée become increasingly fine away from the stream channel, and even finer sediments — clay, silt, and fine sand — are deposited across most of the flood plain. [SE]](http://opentextbc.ca/geology/wp-content/uploads/sites/110/2015/08/natural-levées.png)