Chapter 6 Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

6.5 Groups, Formations, and Members

Geologists who study sedimentary rocks need ways to divide them into manageable units, and they also need to give those units names so that they can easily be referred to and compared with other rocks deposited in other places. The International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) (http://www.stratigraphy.org/) has established a set of conventions for grouping, describing, and naming sedimentary rock units.

The main stratigraphic unit is a formation, which according to the ICS, should be established with the following principles in mind:

The contrast in lithology between formations required to justify their establishment varies with the complexity of the geology of a region and the detail needed for geologic mapping and to work out its geologic history. No formation is considered justifiable and useful that cannot be delineated at the scale of geologic mapping practiced in the region. The thickness of formations may range from less than a meter to several thousand meters.

In other words, a formation is a series of beds that is distinct from other beds above and below, and is thick enough to be shown on the geological maps that are widely used within the area in question. In most parts of the world, geological mapping is done at a relatively coarse scale, and so most formations are in the order of a few hundred metres thick. At that thickness, a typical formation would appear on a typical geological map as an area that is at least a few millimetres thick.

A series of formations can be classified together to define a group, which could be as much as a few thousand metres thick, and represents a series of rocks that were deposited within a single basin (or a series of related and adjacent basins) over a few million to a few tens of millions of years.

In areas where detailed geological information is needed (for example, within a mining or petroleum district) a formation might be divided into members, where each member has a specific and distinctive lithology. For example, a formation that includes both shale and sandstone might be divided into members, each of which is either shale or sandstone. In some areas, where particular detail is needed, members may be divided into beds, but this is only applicable to beds that have a special geological significance. Groups, formations, and members are typically named for the area where they are found.

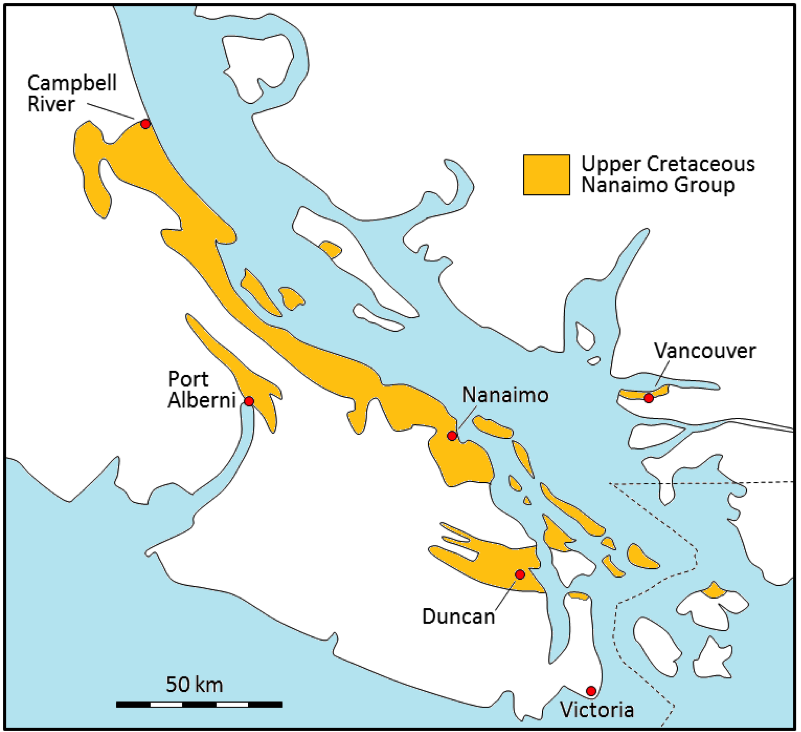

The sedimentary rocks of the Nanaimo Group provide a useful example for understanding groups, formations, and members. During the latter part of the Cretaceous Period, from about 90 Ma to 65 Ma, a thick sequence of clastic rocks was deposited in a foreland basin between what is now Vancouver Island and the B.C. mainland (Figure 6.25). The Nanaimo Group strata comprise a 5000 m thick sequence of conglomerate, sandstone, and mudstone layers. Coal was mined from Nanaimo Group rocks from around 1850 to 1950 in the Nanaimo region, and is still being mined in the Campbell River area.

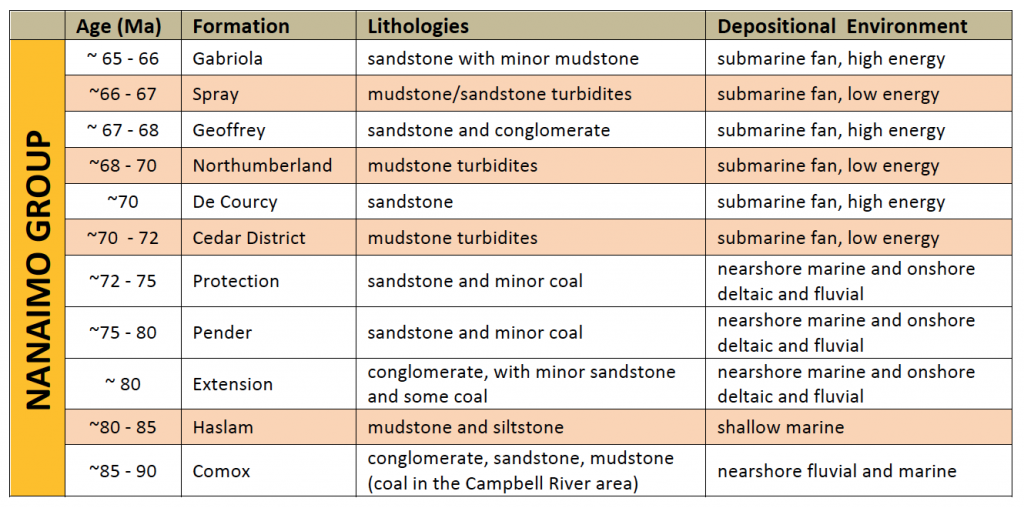

The Nanaimo Group is divided into 11 formations as described in Table 6.4. In general, the boundaries between formations are based on major lithological differences. As can be seen in the far-right column of Table 6.4, a wide range of depositional environments existed during the accumulation of the Nanaimo Group rocks, from nearshore marine for the Comox and Haslam Formation, to fluvial and deltaic with backwater swampy environments for the coal-bearing Extension, Pender, and Protection Formations, to a deep-water submarine fan environment for the upper six formations. The differences in the depositional environments are probably a product of variations in tectonic-related uplift over time.

The five lower formations of the Nanaimo Group are all exposed in the Nanaimo area, and were well studied during the coal mining era between 1850 and 1950. All of these formations (except Haslam) have been divided into members, as that was useful for understanding the rocks in the areas where coal mining was taking place.

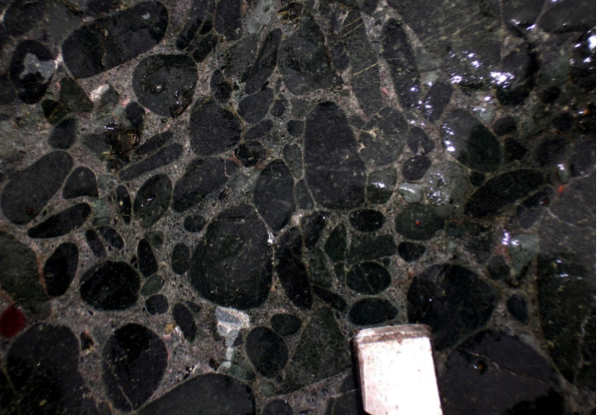

Although there is a great deal of variety in the Nanaimo Group rocks, and it would take hundreds of photographs to illustrate all of the different types of rocks, a few representative examples are provided in Figure 6.26.

Attributions

Figure 6.25

Redrawn based on Mustard, P., 1994, The Upper Cretaceous Nanaimo Group, Georgia Basin, in J. Monger (ed) Geology and Geological Hazards of the Vancouver Region, Geol. Survey of Canada, Bull. 481, pp. 27-95