Chapter 4: Methods of teaching with an online focus

4.7 ‘Agile’ Design: flexible designs for learning

4.7.1 The need for more agile design models

Adamson (2012) states:

The systems under which the world operates and the ways that individual businesses operate are vast and complex – interconnected to the point of confusion and uncertainty. The linear process of cause and effect becomes increasingly irrelevant, and it is necessary for knowledge workers to begin thinking in new ways and exploring new solutions.

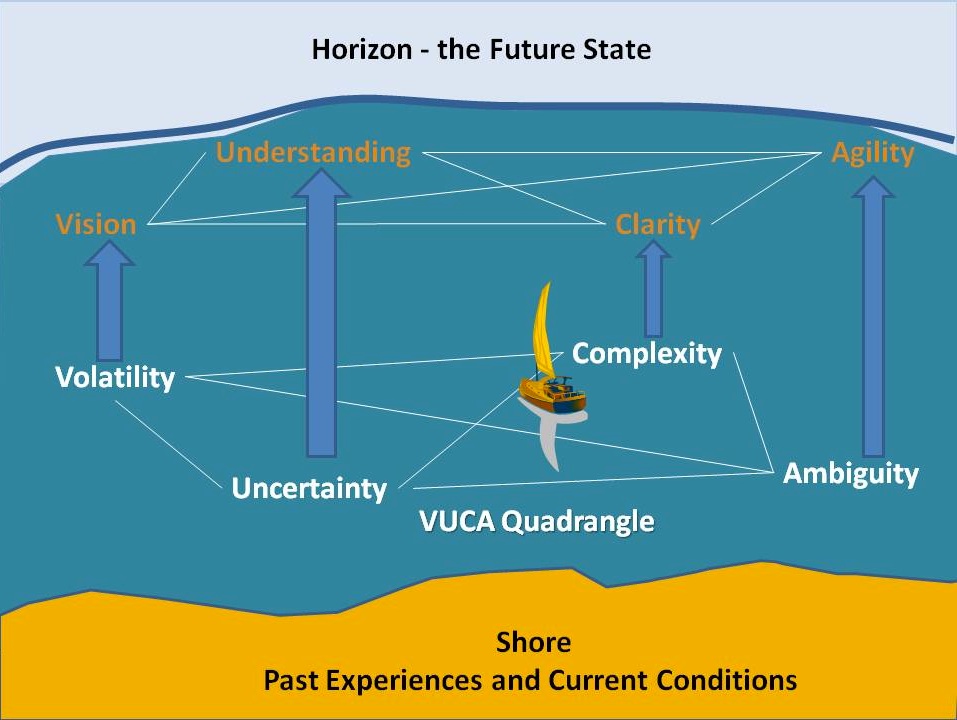

In particular, knowledge workers must deal with situations and contexts that are volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous (what Adamson calls a VUCA environment). This certainly applies to teachers working with ever new, emerging technologies, very diverse students, and a rapidly changing external world that puts pressure on institutions to change.

If we look at course design, how does a teacher respond to rapidly developing new content, new technologies or apps being launched on a daily basis, to a constantly changing student base, to pressure to develop the knowledge and skills that are needed in a digital age? For instance, even setting prior learning outcomes is fraught in a VUCA environment, unless you set them at an abstract ‘skill’ level such as thinking flexibly, networking, and information retrieval and analysis. Students need to develop the key knowledge management skills of knowing where to find relevant information, how to assess, evaluate and appropriately apply such information. This means exposing students to less than certain knowledge and providing them with the skills, practice and feedback to assess and evaluate such knowledge, then apply that to solving real world problems.

In order to do this, learning environments need to be created that are rich and constantly changing, but which at the same time enable students to develop and practice the skills and acquire the knowledge they will need in a volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous world.

Image: © Carol Mase, Free Management Library, 2011, used with permission

4.7.2 Core features of agile design models

Describing the design features of this model is a challenge, for two reasons. First, there is no single approach to agile design. The whole point is to be adaptable to the circumstances in which it operates. Second, it is only with the development of light, easy to use technology and media in the last few years that instructors and course designers have started to break away from the standard design models, so agile designs are still emerging. However, this is a challenge that software designers have also been facing (see for instance, Larman and Vodde, 2009; Ries, 2011) and perhaps there are lessons that can be applied to educational design.

First, it is important to distinguish ‘agile’ design from rapid instructional design (Meier, 2000) or rapid prototyping, which are really both streamlined versions of the ADDIE model. Although rapid instructional design/rapid protyping enable courses or modules to be designed more quickly (especially important for corporate training), they still follow the same kind of sequential or iterative processes as in the ADDIE model, but in a more compressed form. Rapid instructional design and rapid prototyping might be considered particular kinds of agile design, but they lack some of the most important characteristics outlined below:

4.7.2.1 Light and nimble

If ADDIE is a 100-piece orchestra, with a complex score and long rehearsals, then agile design is a jazz trio who get together for a single performance then break up until the next time. Although there may be a short preparation time before the course starts, most of the decisions about what will go into the course, what tools will be used, what activities learners will do, and sometimes even how students will be assessed, are decided as the course progresses.

On the teaching side, there are usually only a few people involved in the actual design, one or sometimes two instructors and possibly an instructional designer, who nevertheless meet frequently during the offering of the course to make decisions based on feedback from learners and how learners are progressing through the course. However, many more content contributors may be invited – or spontaneously offer – to participate on a single occasion as the course progresses.

4.7.2.2 Content, learner activities, tools used and assessment vary, according to the changing environment

The content to be covered in a course is likely to be highly flexible, based more on emerging knowledge and the interests or prior experience of the learners, although the core skills that the course aims to develop are more likely to remain constant. For instance, for ETEC 522 in Scenario F, the overall objective is to develop the skills needed to be a pioneer or innovator in education, and this remains constant over each iteration of the course. However, because the technology is rapidly developing with new products, apps and services every year, the content of the course is quite different from year to year.

Also learner activities and methods of assessment are also likely to change, because students can use new tools or technology themselves for learning as they become available. Very often learners themselves seek out and organise much of the core content of the course and are free to choose what tools they use.

4.7.2.3 The design attempts to exploit the affordances of either existing or emerging technologies

Agile design aims to exploit fully the educational potential of new tools or software, which means sometimes changing at least sub-goals. This may mean developing different skills in learners from year to year, as the technology changes and allows new things to be done. The emphasis here is not so much on doing the same thing better with new technology, but striving for new and different outcomes that are more relevant in a digital world.

ETEC 522 for instance did not start with a learning management system. Instead, a web site, built in WordPress, was used as the starting point for student activities, because students as well as instructors were posting content, but in another year the content focus of the course was mainly on mobile learning, so apps and other mobile tools were strong components of the course.

4.7.2.4 Sound, pedagogical principles guide the overall design of a course – to a point

Just as most successful jazz trios work within a shared framework of melody, rhythm, and musical composition, so is agile design shaped by overarching principles of best practice. Most successful agile designs have been guided by core design principles associated with ‘good’ teaching, such as clear learning outcomes or goals, assessment linked to these goals, strong learner support, including timely and individualised feedback, active learning, collaborative learning, and regular course maintenance based on learner feedback, all within a rich learning environment (see Appendix 1). Sometimes though deliberate attempts are made to move away from an established best practice for experimental reasons, but usually on a small scale, to see if the experiment works without risking the whole course.

4.7.2.5 Experiential, open and applied learning

Usually agile course design is strongly embedded in the real, external world. Much or all the course may be open to other than registered students. For instance, much of ETEC 522, such as the final YouTube business pitches, is openly available to those interested in the topics. Sometimes this results in entrepreneurs contacting the course with suggestions for new tools or services, or just to share experience.

Another example is a course on Latin American studies from a Canadian university. This particular course had an open, student-managed wiki, where they could discuss contemporary events as they arose. This course was active at the same time that the Argentine government nationalised the Spanish oil company, Repsol. Several students posted comments critical of the government action, but after a week, a professor from a university in Argentina, who had come across the wiki by accident while searching the Internet, responded, laying out a detailed defence of the government’s policy. This was then made a formal topic for discussion within the course.

Such courses may though be only partially open. Discussion of sensitive subjects for instance may still take place behind a password controlled discussion forum, while other parts of the course may be open to all. As experience grows in this kind of design, other and perhaps clearer design principles are likely to emerge.

4.7.3 Strengths and weaknesses of flexible design models

The main advantage of agile design is that it focuses directly on preparing students for a volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous world. It aims explicitly at helping students develop many of the specific skills they will need in a digital age, such as knowledge management, multimedia communication skills, critical thinking, innovation, and digital literacy embedded within a subject domain. Where agile design has been successfully used, students have found the design approach highly stimulating and great fun, and instructors have been invigorated and enthusiastic about teaching. Agile design enables courses to be developed and offered quickly and at much lower initial cost than ADDIE-based approaches.

However, agile design approaches are very new and have not really been much written about, never mind evaluated. There is no ‘school’ or set of agreed principles to follow, although there are similarities between the agile approach to design for learning with ‘agile’ design for computer software. Indeed it could be argued that most of the things in agile design are covered in other teaching models, such as online collaborative learning or experiential learning. Despite this, innovative instructors are beginning to develop courses in a similar way to ETEC 522 and there is a consistency in the basic design principles that give them a certain coherence and shape, even though each course or program appears on the surface to be very different (another example of agile design, but campus-based, with quite a different overall program from ETEC 522, is the Integrated Science program at McMaster University.)

Certainly agile design approaches require confident instructors willing to take a risk, and success is heavily dependent on instructors having a good background in best teaching practices and/or strong instructional design support from innovative and creative instructional designers. Because of the relative lack of experience in such design approaches the limitations are not well identified yet. For instance, this approach can work well with relatively small class sizes but how well will it scale? Successful use probably also depends on learners already having a good foundational knowledge base in the subject domain. Nevertheless I expect more agile designs for learning to grow over the coming years, because they are more likely to meet the needs of a VUCA world.

Activity 4.7 Taking risks with ‘agile’ design

1. Do you think a ‘agile’/flexible design approach will increase or undermine academic excellence? What are your reasons?

2. Would you like to try something like this in your own teaching (or are you already doing something like this)? What would be the risks and benefits in your subject area of doing this?

References

Adamson, C. (2012) Learning in a VUCA world, Online Educa Berlin News Portal, November 13

Meier, D. (2000). The Accelerated Learning Handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill

Ries, E. (2011) The Lean Start-Up New York: Crown Business/Random House