Chapter 11: Ensuring quality teaching in a digital age

11.6 Step four: build on existing resources

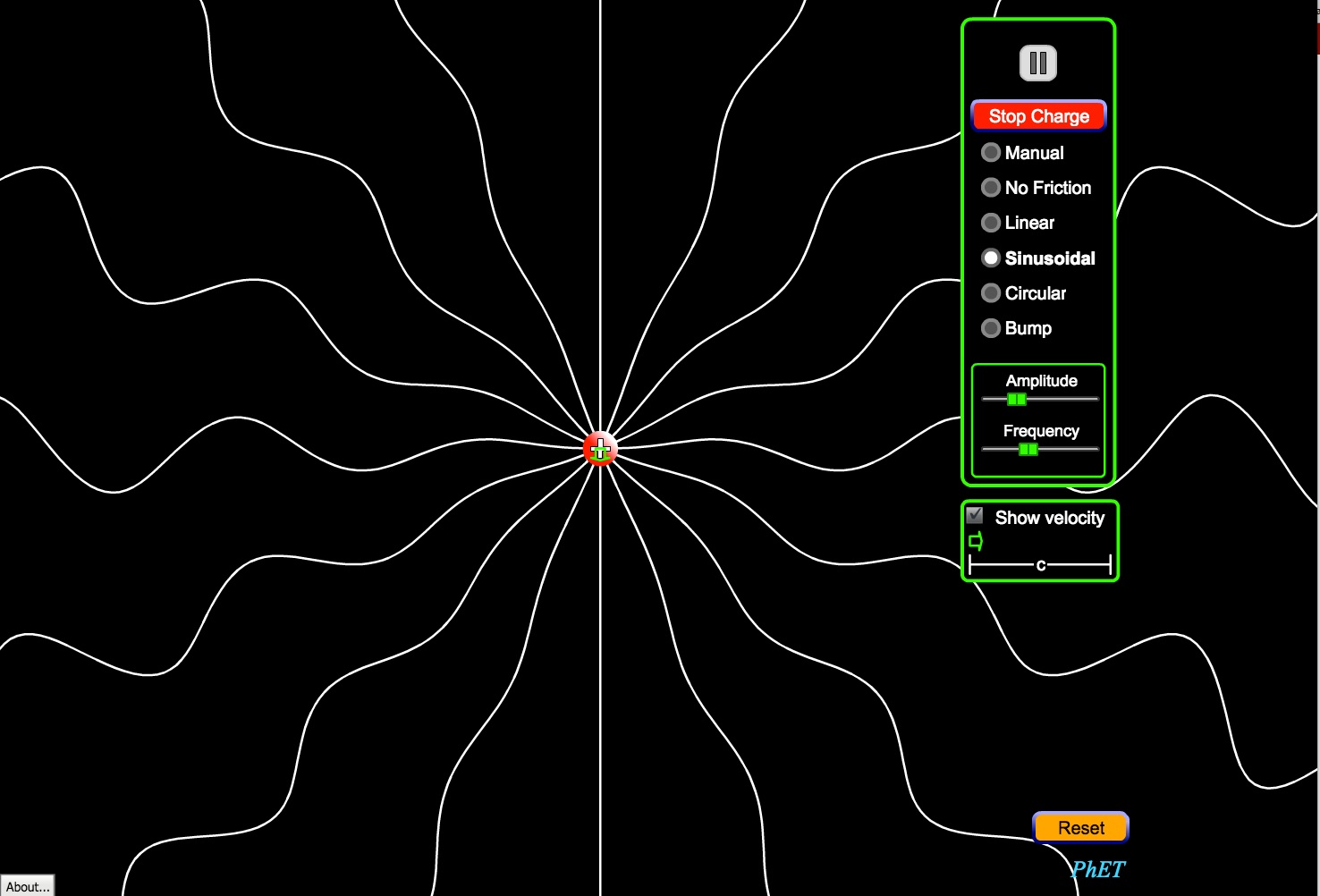

Image: © University of Colorado-Boulder

The importance of using existing resources has been stressed in several parts of the book, particularly Chapters 7 and 10 .

11.6.1 Moving content online

Time management for teachers and instructors is critical. A great deal of time can be spent converting classroom material into a form that will work in an online environment, but this can really increase workload. For instance, PowerPoint slides without a commentary often either miss the critical content, or fail to cover nuances and emphasis. This may mean either using lecture capture to record the lecture, or having to add a recorded commentary over the slides at a later date. Transferring lecture notes into pdf files and loading them up into a learning management system is also time consuming. However, this is not the best way to develop online materials, both for time management and pedagogical reasons.

In Step 1 I recommended rethinking teaching, not just moving recorded lectures or class PowerPoint slides online, but developing materials in ways that enable students to learn better. Now in Step 4 I appear to be contradicting that by suggesting that you should use existing resources. However, the distinction here is between using existing resources that do not transfer well to an online learning environment (such as a 50 minute recorded lecture), and using materials already specifically developed or suitable for learning in an online environment.

11.6.2 Use existing online content

The Internet, and in particular the World Wide Web, has an immense amount of content already available, and this was discussed extensively in Chapter 10. Much of it is freely available for educational use, under certain conditions (e.g. acknowledgement of the source – look for the Creative Commons license usually at the end of the web page). You will find such existing content varies enormously in quality and range. Top universities such as MIT, Stanford, Princeton and Yale have made available recordings of their classroom lectures , etc., while distance teaching organizations such as the UK Open University have made all their online teaching materials available for free use. Much of this can be found at these sites:

- OpenCourseWare (MIT)

- iTunesU

- OpenLearn (U.K. Open University)

- The Open Education Consortium (courses in STEM: science, technology, engineering, math)

- Open Learning Initiative (Carnegie Mellon)

However, there are now many other sites from prestigious universities offering open course ware. (A Google search using ‘open educational resources’ or’ OER’ will identify most of them.)

In the case of the prestigious universities, you can be sure about the quality of the content – it’s usually what the on-campus students get – but it often lacks the quality needed in terms of instructional design or suitability for online learning (for more discussion on this see Keith Hampson’s: MOOCs: The Prestige Factor; or OERs: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly). Open resources from institutions such as the UK Open University or Carnegie Mellon’s Open Learn Initiative usually combine quality content with good instructional design.

Where open educational resources are particularly valuable are in their use as interactive simulations, animations or videos that would be difficult or too expensive for an individual instructor to develop. Examples of simulations in science subjects such as biology and physics can be found here: PhET, or at the Khan Academy for mathematics, but there are many other sources as well.

But as well as open resources designated as ‘educational’, there is a great deal of ‘raw’ content on the Internet that can be invaluable for teaching. The main question is whether you as the instructor need to find such material, or whether it would be better to get students to search, find, select, analyze, evaluate and apply information. After all, these are key skills for a digital age that students need to have.

Certainly at k-12, two-year college or undergraduate level, most content is not unique or original. Most of the time we are standing on the shoulders of giants, that is, organizing and managing knowledge already discovered. Only in the areas where you have unique, original research that is not yet published, or where you have your own ‘spin’ on content, is it really necessary to create ‘content’ from scratch. Unfortunately, though, it can still be difficult to find exactly the material you want, at least in a form that would be appropriate for your students. In such cases, then it will be necessary to develop your own materials, and this is discussed further in Step 7. However, building a course around already existing materials will make a lot of sense in many contexts.

11.6.3 Conclusion

You have a choice of focusing on content development or on facilitating learning. As time goes on, more and more of the content within your courses will be freely available from other sources over the Internet. This is an opportunity to focus on what students need to know, and on how they can find, evaluate and apply it. These are skills that will continue well beyond the memorisation of content that students gain from a particular course. So it is important to focus just as much on student activities, what they need to do, as on creating original content for our courses. This is discussed in more detail in Steps 6, 7 and 8.

So a critical step before even beginning to teach a course is look around and see what’s available and how this could potentially be used in the course or program you are planning to teach.

Activity 11.6 Building on existing resources

1. How original is the content you are teaching? Could students learn just as well from already existing content? If not, what is the ‘extra’ you are adding? How will you incorporate the added value of your own contribution in your course design?

2. Does the content you are already thinking of covering already exist on the web? Have you looked to see what’s already there? What if any are the restrictions on its re-use for educational purposes?

3. What are your colleagues doing online – or indeed in the classroom, with respect to digital teaching? Could you work together to jointly develop and/or share materials?

If you feel that your course is currently too much work, then maybe the answers to these questions may indicate where the problem lies.