Chapter 1: Fundamental Change in Education

1.7 From the periphery to the center: how technology is changing the way we teach

We shall see in Chapter 6, Section 2 that technology has always played an important role in teaching from time immemorial, but until recently, it has remained more on the periphery of education. Technology has been used mainly to support regular classroom teaching, or operated in the form of distance education, for a minority of students or in specialized departments (often in continuing education or extension). However, in the last ten to fifteen years, technology has been increasingly influencing the core teaching activities of even universities. Some of the ways technology is moving from the periphery to the centre can be seen from the following trends.

1.7.1. Fully online learning

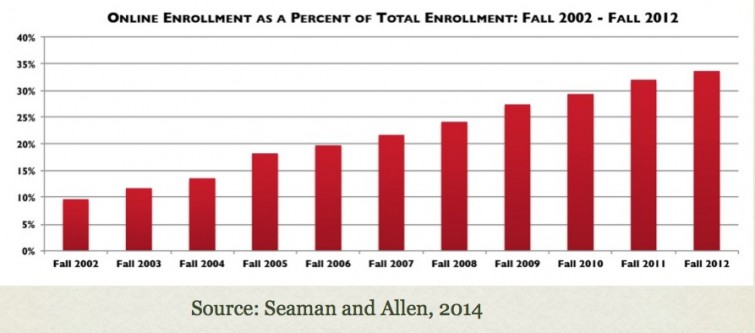

Credit-based online learning is now becoming a major and central activity of most academic departments in universities, colleges and to some extent even in school/k-12 education. Enrolments in fully online courses (i.e. distance education courses) now constitute between a quarter and a third of all post-secondary enrolments in the USA (Allen and Seaman, 2014). Online learning enrolments have been increasing by between 10-20 per cent per annum for the last 15 years or so in North America, compared with an increase in campus-based enrolments of around 2-3 per cent per annum. There are now at least seven million students in the USA taking at least one fully online course, with almost one million online course enrolments in just the California Community College System (Johnson and Mejia, 2014). Fully online learning then is now a key component of many school and post-secondary education systems.

1.7.2. Blended and hybrid learning

As more instructors have become involved in online learning, they have realised that much that has traditionally been done in class can be done equally well or better online (a theme that will be explored more in Chapter 9). As a result, instructors have been gradually introducing more online study elements into their classroom teaching. So learning management systems may be used to store lecture notes in the form of slides or PDFs, links to online readings may be provided, or online forums for discussion may be established. Thus online learning is gradually blended with face-to-face teaching, but without changing the basic classroom teaching model. Here online learning is being used as a supplement to traditional teaching. Although there is no standard or commonly agreed definitions in this area, I will use the term ‘blended learning’ for this use of technology.

More recently, though, lecture capture has resulted in instructors realising that if the lecture is recorded, students could view this in their own time, and then the classroom time could be used for more interactive sessions. This model has become known as the ‘flipped classroom’.

Some institutions are now developing plans to move a substantial part of their teaching into more blended or flexible modes. For instance the University of Ottawa is planning to have at least 25 per cent of its courses blended or hybrid within five years (University of Ottawa, 2013). The University of British Columbia is planning to redesign most of its first and second year large lecture classes into hybrid classes (Farrar, 2014).

The implications of both fully online and blended learning will be discussed more fully in Chapter 9.

1.7.3. Open learning

Another increasingly important development linked to online learning is the move to more open education. Over the last 10 years there have been developments in open learning that are beginning to impact directly on conventional institutions. The most immediate is open textbooks – such as what you are reading now. Open textbooks are digital textbooks that can be downloaded in a digital format by students (or instructors) for free, thus saving students considerable money on textbooks. For instance, in Canada, the three provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, and Saskatchewan have agreed to collaborate on the production and distribution of peer-reviewed open textbooks for the 40 high-enrolment subject areas in their university and community college programs.

Open educational resources (OER) are another recent development in open education. These are digital educational materials freely available over the Internet that can be downloaded by instructors (or students) without charge, and if necessary adapted or amended, under a Creative Commons license that provides protections for the creators of the material. Probably the best known source of OER is the Massachusetts Institute of Technology OpenCourseWare project. With individual professors’ permission, MIT has made available for free downloading over the Internet video lectures recorded with lecture capture as well as supporting materials such as slides.

The implications of developments in open learning will also be discussed in Chapter 10.

1.7.4. MOOCs

One of the main developments in online learning has been the rapid growth of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). In 2008, the University of Manitoba in Canada offered the first MOOC with just over 2,000 enrolments, which linked webinar presentations and/or blog posts by experts to participants’ blogs and tweets. The courses were open to anyone and had no formal assessment. In 2012, two Stanford University professors launched a lecture-capture based MOOC on artificial intelligence, attracting more than 100,000 students, and since then MOOCs have expanded rapidly around the world.

Although the format of MOOCs can vary, in general they have the following characteristics:

- open to anyone to enroll and simple enrollment (just an e-mail address)

- very large numbers (from 1,000 to 100,000)

- free access to video-recorded lectures, often from the most elite universities in the USA (Harvard, MIT, Stanford in particular).

- computer-based assessment, usually using multiple-choice questions and immediate feedback, combined sometimes with peer assessment

- a wide range of commitment from learners: up to 50 per cent never do more than register, 25 per cent never take more than the first assignment, less than 10 per cent complete the final assessment.

However, MOOCs are merely the latest example of the rapid evolution of technology, the over-enthusiasm of early adopters, and the need for careful analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of new technologies for teaching. At the time of writing, the future of MOOCs is difficult to forecast. They will certainly evolve over time, and will probably find some kind of niche in the higher education market.

MOOCs will be discussed more fully in Chapter 5.

1.7.5 Managing the changing landscape of education

These rapid developments in educational technologies mean that faculty and instructors need a strong framework for assessing the value of different technologies, new or existing, and for deciding how or when these technologies make sense for them and their students to use. Blended and online learning, social media and open learning are all developments that are critical for effective teaching in a digital age.

References

Allen, I. and Seaman, J. (2014) Grade Change: Tracking Online Learning in the United States Wellesley MA: Babson College/Sloan Foundation

Farrar, D. (2014) Flexible Learning: September 2014 Update Flexible Learning, University of British Columbia

Johnson, H. and Mejia, M. (2014) Online learning and student outcomes in California’s community colleges San Francisco CA: Public Policy Institute of California

University of Ottawa (2013) Report of the e-Learning Working Group Ottawa ON: University of Ottawa