Chapter 8: Choosing and using media in education: the SECTIONS model

8.9 Security and privacy

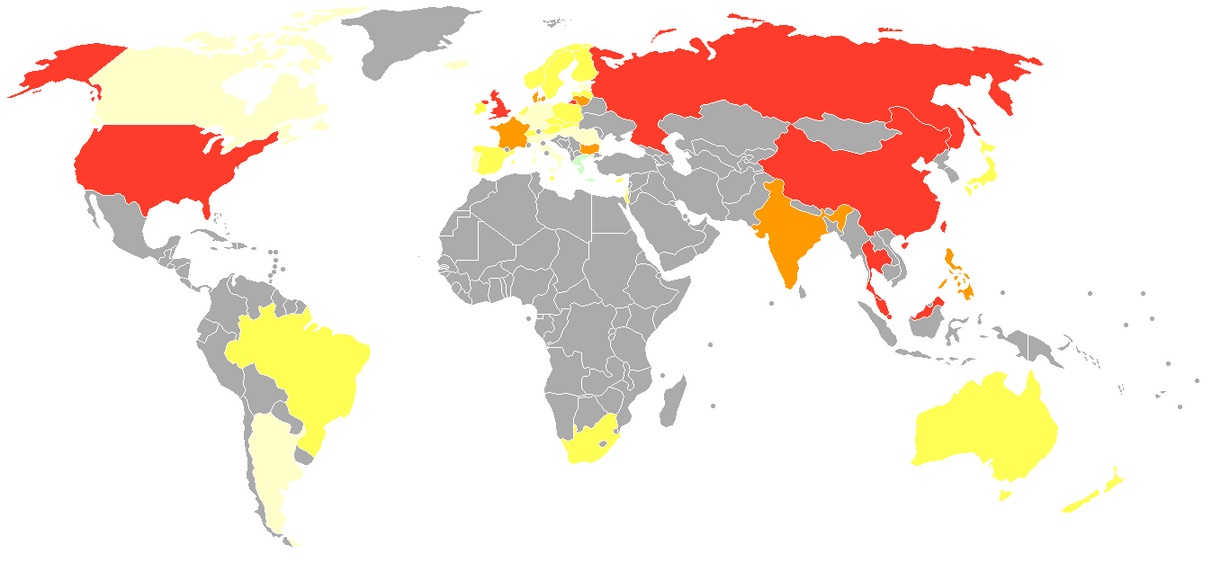

Red: Endemic surveillance societies

Strong yellow: Systemic failure to uphold safeguards

Pale yellow: Some safeguards but weakened protections

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Privacy#mediaviewer/File:Privacy_International_2007_privacy_ranking_map.png

This too is a change from earlier versions of the SECTIONS model, where ‘S’ stood for speed, in terms of how quickly a technology enabled a course to be developed.. However, the issues that I previously raised under speed have also been included in Section 8.3, ‘Ease of Use’. This has allowed me to replace ‘Speed’ with ‘Security and privacy’, which have become increasingly important issues for education in a digital age.

8.9.1 The need for privacy and security when teaching

Teachers, instructors and students need a private place to work online. Instructors want to be able to criticize politicians or corporations without fear of reprisal; students may want to keep rash or radical comments from going public or will want to try out perhaps controversial ideas without having them spread all over Facebook. Institutions want to protect students from personal data collection for commercial purposes by private companies, tracking of their online learning activities by government agencies, or marketing and other unrequested commercial or political interruption to their studies. In particular, institutions want to protect students, as far as possible, from online harassment or bullying. Creating a strictly controlled environment enables institutions to manage privacy and security more effectively.

Learning management systems provide password protected access to registered students and authorised instructors. Learning management systems were originally housed on servers managed by the institution itself. Password protected LMSs on secure servers have provided that protection. Institutional policies regarding appropriate online behaviour can be managed more easily if the communications are managed ‘in-house.’

8.9.2 Cloud based services and privacy

However, in recent years, more and more online services have moved ‘to the cloud’, hosted on massive servers whose physical location is often unknown even to the institution’s IT services department. Contract agreements between an educational institution and the cloud service provider are meant to ensure security and back-ups.

Nevertheless, Canadian institutions and privacy commissioners have been particularly wary of data being hosted out of country, where it may be accessed through the laws of another country. There has been concern that Canadian student information and communications held on cloud servers in the USA may be accessible via the U.S. Patriot Act. For instance, Klassen (2011) writes:

Social media companies are almost exclusively based in the United States, where the provisions of the Patriot Act apply no matter where the information originates. The Patriot Act allows the U.S. government to access the social media content and the personally identifying information without the end users’ knowledge or consent.

The government of British Columbia, concerned with both the privacy and security of personal information, enacted a stringent piece of legislation to protect the personal information of British Columbians. The Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA) mandates that no personally identifying information of British Columbians can be collected without their knowledge and consent, and that such information not be used for anything other than the purpose for which it was originally collected.

Concerns about student privacy have increased even more when it became known that countries were sharing intelligence information, so there remains a risk that even student data on Canadian-based servers may well be shared with foreign countries.

Perhaps of more concern though is that as instructors and students increasingly use social media, academic communication becomes public and ‘exposed’. Bishop (2011) discusses the risks to institutions in using Facebook:

- privacy is different from security, in that security is primarily a technical, hence mainly an IT, issue. Privacy needs a different set of policies that involves a much wider range of stakeholders within an institution, and hence a different (and more complex) governance approach from security;

- many institutions do not have a simple, transparent set of policies for privacy, but different policies set by different parts of the institution. This will inevitably lead to confusion and difficulties in compliance;

- there is a whole range of laws and regulations that aim to protect privacy; these cover not only students but also staff; privacy policy needs to be consistent across the institution and be compliant with such laws and regulation;

- Facebook’s current privacy policy (2011) leaves many institutions using Facebook at a high level of risk of infringing or violating privacy laws – merely writing some kind of disclaimer will in many cases not be sufficient to avoid breaking the law.

The controversy at Dalhousie University where dental students used Facebook for violent sexist remarks about their fellow women students is an example of the risks endemic in the use of social media.

8.9.3 The need for balance

Although there may well be some areas of teaching and learning where it is essential to operate behind closed doors, such as in some areas of medicine or areas related to public security, or in discussion of sensitive political or moral issues, in general though there have been relatively few privacy or security problems when teachers and instructors have opened up their courses, have followed institutional privacy policies, and above all where students and instructors have used common sense and behaved ethically. Nevertheless, as teaching and learning becomes more open and public, the level of risk does increase.

8.9.4 Questions for consideration

1. What student information am I obliged to keep private and secure? What are my institution’s policies on this?

2. What is the risk that by using a particular technology my institution’s policies concerning privacy could easily be breached? Who in my institution could advise me on this?

3. What areas of teaching and learning, if any, need I keep behind closed doors, available only to students registered in my course? Which technologies will best allow me to do this?

References

Bishop, J. (2011) Facebook Privacy Policy: Will Changes End Facebook for Colleges? The Higher Ed CIO, October 4

Klassen, V. (2011) Privacy and Cloud-Based Educational Technology in British Columbia Vancouver BC: BCCampus

See also:

Bates, T. (2011) Cloud-based educational technology and privacy: a Canadian perspective, Online Learning and Distance Education Resources, March 25