Chapter 4: Methods of teaching with an online focus

Scenario E: Developing historical thinking

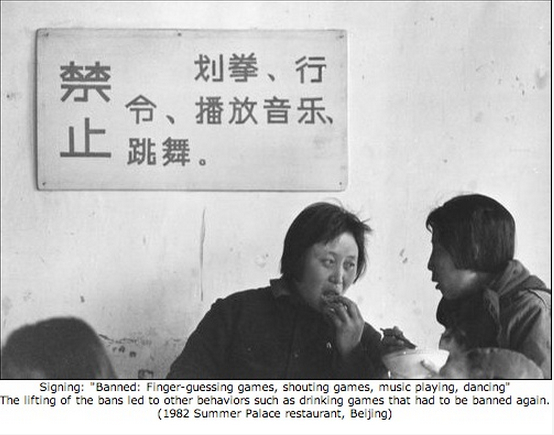

Image: © zonaeuropa.com

Ralph Goodyear is a professor of history in a public research university in the central United States. He has a class of 72 undergraduate students taking HIST 305, ‘Historiography’. For the first three weeks of the course, Goodyear had recorded a series of short 15 minute video lectures that covered the following topics/content:

- the various sources used by historians (e.g. earlier writings, empirical records including registries of birth, marriage and death, eye witness accounts, artifacts such as paintings, photographs, and physical evidence such as ruins);

- the themes around which historical analysis tend to be written;

- some of the techniques used by historians, such as narrative, analysis and interpretation;

- three different positions or theories about history (objectivist, marxist, post modernist).

Students downloaded the videos according to a schedule suggested by Goodyear. Students attended two one hour classes a week, where specific topics covered in the videos were discussed. Students also had an online discussion forum in the course space on the university’s learning management system, where Goodyear had posted similar topics for discussion. Students were expected to make at least one substantive contribution to each online topic for which they received a mark that went towards their final grade. Students also had to read a major textbook on historiography over this three week period.

In the fourth week, he divided the class into twelve groups of six, and asked each group to research the history of any city outside the United States over the last 50 years or so. They could use whatever sources they could find, including online sources such as newspaper reports, images, research publications, and so on, as well as the university’s own library collection. In writing their report, they had to do the following:

- pick a particular theme that covered the 50 years and write a narrative based around the theme;

- identify the sources they finally used in their report, and discuss why they selected some sources and dismissed others;

- compare their approach to the three positions covered in the lectures;

- post their report in the form of an online e-portfolio in the course space on the university’s learning management system.

They had five weeks to do this.

The last three weeks of the course were devoted to presentations by each of the groups, with comments, discussion and questions, both in class and online (the in class presentations were recorded and made available online). At the end of the course, students assigned grades to each of the other groups’ work. Goodyear took these student gradings into consideration, but reserved the right to adjust the grades, with an explanation of why he did the adjustment. Goodyear also gave each student an individual grade, based on both their group’s grade, and their personal contribution to the online and class discussions.

Goodyear commented that he was surprised and delighted at the quality of the students’ work. He said: ‘What I liked was that the students weren’t learning about history; they were doing it.’

Based on an actual case, but with some embellishments.