Chapter 2: The nature of knowledge and the implications for teaching

2.6 Connectivism

2.6.1 What is connectivism?

Another epistemological position, connectivism, has emerged in recent years that is particularly relevant to a digital society. Connectivism is still being refined and developed, and it is currently highly controversial, with many critics.

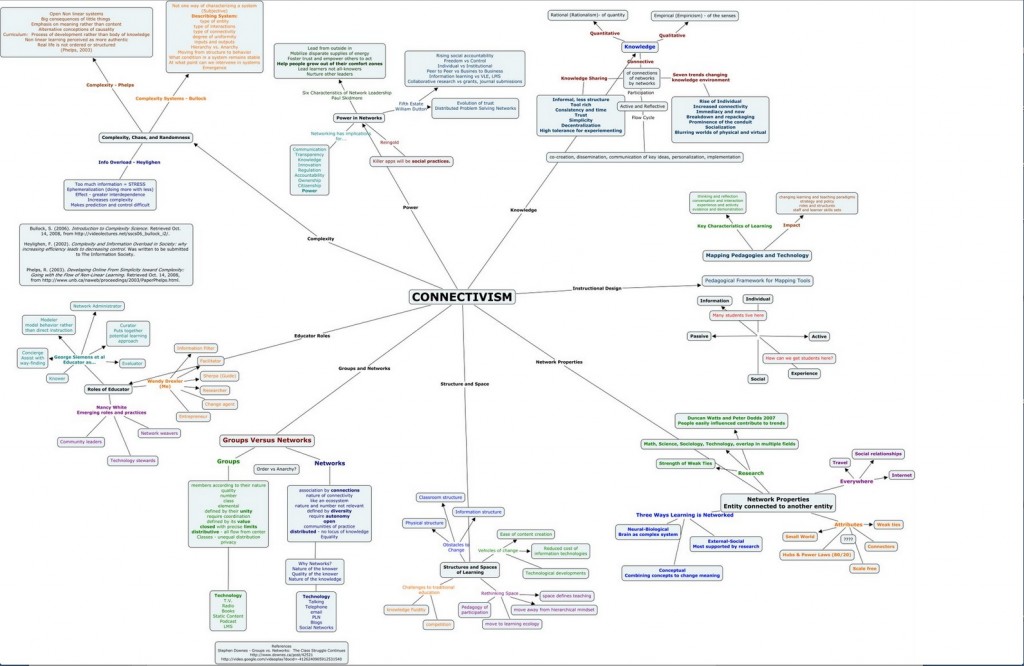

In connectivism it is the collective connections between all the ‘nodes’ in a network that result in new forms of knowledge. According to Siemens (2004), knowledge is created beyond the level of individual human participants, and is constantly shifting and changing. Knowledge in networks is not controlled or created by any formal organization, although organizations can and should ‘plug in’ to this world of constant information flow, and draw meaning from it. Knowledge in connectivism is a chaotic, shifting phenomenon as nodes come and go and as information flows across networks that themselves are inter-connected with myriad other networks.

The significance of connectivism is that its proponents argue that the Internet changes the essential nature of knowledge. ‘The pipe is more important than the content within the pipe,’ to quote Siemens again.

Downes (2007) makes a clear distinction between constructivism and connectivism:

‘In connectivism, a phrase like “constructing meaning” makes no sense. Connections form naturally, through a process of association, and are not “constructed” through some sort of intentional action. …Hence, in connectivism, there is no real concept of transferring knowledge, making knowledge, or building knowledge. Rather, the activities we undertake when we conduct practices in order to learn are more like growing or developing ourselves and our society in certain (connected) ways.’

2.6.2 Connectivism and learning

For Siemens (2005), it is the connections and the way information flows that result in knowledge existing beyond the individual. Learning becomes the ability to tap into significant flows of information, and to follow those flows that are significant. He argues that:

‘Connectivism presents a model of learning that acknowledges the tectonic shifts in society where learning is no longer an internal, individualistic activity….Learning (defined as actionable knowledge) can reside outside of ourselves (within an organization or a database).’

Siemens (2005) identifies the principles of connectivism as follows:

- Learning and knowledge rests in diversity of opinions.

- Learning is a process of connecting specialized nodes or information sources.

- Learning may reside in non-human appliances.

- Capacity to know more is more critical than what is currently known

- Nurturing and maintaining connections is needed to facilitate continual learning.

- Ability to see connections between fields, ideas, and concepts is a core skill.

- Currency (accurate, up-to-date knowledge) is the intent of all connectivist learning activities.

- Decision-making is itself a learning process. Choosing what to learn and the meaning of incoming information is seen through the lens of a shifting reality. While there is a right answer now, it may be wrong tomorrow due to alterations in the information climate affecting the decision.

Downes (2007) states that:

‘at its heart, connectivism is the thesis that knowledge is distributed across a network of connections, and therefore that learning consists of the ability to construct and traverse those networks….[Connectivism] implies a pedagogy that:

(a) seeks to describe ‘successful’ networks (as identified by their properties, which I have characterized as diversity, autonomy, openness, and connectivity) and

(b) seeks to describe the practices that lead to such networks, both in the individual and in society – which I have characterized as modelling and demonstration (on the part of a teacher) – and practice and reflection (on the part of a learner).

2.6.3 Applications of connectivism to teaching and learning

Siemens, Downes and Cormier constructed the first massive open online course (MOOC), Connectivism and Connective Knowledge 2011, partly to explain and partly to model a connectivist approach to learning.

Connectivists such as Siemens and Downes tend to be somewhat vague about the role of teachers or instructors, as the focus of connectivism is more on individual participants, networks and the flow of information and the new forms of knowledge that result. The main purpose of a teacher appears to be to provide the initial learning environment and context that brings learners together, and to help learners construct their own personal learning environments that enable them to connect to ‘successful’ networks, with the assumption that learning will automatically occur as a result, through exposure to the flow of information and the individual’s autonomous reflection on its meaning. There is no need for formal institutions to support this kind of learning, especially since such learning often depends heavily on social media readily available to all participants.

There are numerous criticisms of the connectivist approach to teaching and learning (see Chapter 6, Section 4). Some of these criticisms may be overcome as practice improves, as new tools for assessment, and for organizing co-operative and collaborative work with massive numbers, are developed, and as more experience is gained. More importantly, connectivism is really the first theoretical attempt to radically re-examine the implications for learning of the Internet and the explosion of new communications technologies.

Activity 2.6 Defining the limits of connectivism

1. What areas of knowledge do you think would be best ‘taught’ or learned through a connectivist approach?

2. What areas of knowledge do you think would NOT be appropriately taught through a connectivist approach?

3. What are your reasons?

You might like to come back to your answer after you have read Chapter 6 on MOOCs.

References and further reading

AlDahdouh, A., Osório, A., Caires, S. (2015) Understanding knowledge network, learning and connectivism, International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, Vol. 12, No.10

Downes, S. (2007) What connectivism is Half An Hour, February 3

Downes, S. (2014) The MOOC of One, Stephen’s Web, March 10

Siemens, G. (2005) ‘Connectivism: a theory for the digital age’ International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, Vol. 2, No. 1.