Chapter 11: Ensuring quality teaching in a digital age

11.9 Step seven: design course structure and learning activities

Image: © Arisean Reach, 2012

The importance of providing students with a structure for learning and setting appropriate learning activities is probably the most important of all the steps towards quality teaching and learning, and yet the least discussed in the literature on quality assurance.

11.9.1 Some general observations about structure in teaching

First a definition, since this is a topic that is rarely directly discussed in either face-to-face or online teaching, despite structure being one of the main factors that influences learner success.

Three dictionary definitions of structure are as follows:

1. Something made up of a number of parts that are held or put together in a particular way.

2. The way in which parts are arranged or put together to form a whole

3. The interrelation or arrangement of parts in a complex entity.

Teaching structure would include two critical and related elements:

- the choice, breakdown and sequencing of the curriculum (content);

- the deliberate organization of student activities by teacher or instructor (skills development; and assessment).

This means that in a strong teaching structure, students know exactly what they need to learn, what they are supposed to do to learn this, and when and where they are supposed to do it. In a loose structure, student activity is more open and less controlled by the teacher (although a student may independently decide to impose his or her own ‘strong’ structure on their learning). The choice of teaching structure of course has implications for the work of teachers and instructors as well as students.

In terms of the definition, ‘strong’ teaching structure is not inherently better than a ‘loose’ structure, nor inherently associated with either face-to-face or online teaching. The choice (as so often in teaching) will depend on the specific circumstances. However, choosing the optimum or most appropriate teaching structure is critical for quality teaching and learning, and while the optimum structures for online teaching share many common features with face-to-face teaching, in other ways they differ considerably.

The three main determinants of teaching structure are:

(a) the organizational requirements of the institution;

(b) the preferred philosophy of teaching of the instructor;

(c) the instructor’s perception of the needs of the students.

11.9.2 Institutional organizational requirements of face-to-face teaching

Although the institutional structure in face-to-face teaching is so familiar that it is often unnoticed or taken for granted, institutional requirements are in fact a major determinant of the way teaching is structured, as well as influencing both the work of teachers and the life of students. I list below some of the institutional requirements that influence the structure of face-to-face teaching in post-secondary education:

- the minimum number of years of study required for a degree;

- the program approval and review process;

- the number of credits required for a degree;

- the relationship between credits and contact time in the class;

- the length of a semester and its relationship to credit hours;

- instructor:student ratios;

- the availability of classroom or laboratory spaces;

- time and location of examinations.

There are probably many more. There are similar institutional organizational requirements in the school system, including the length of the school day, the timing of holidays, and so on. (To understand the somewhat bizarre reasons why the Carnegie Unit based on a Student Study Hour came to be adopted in the USA, see Wikipedia.)

As our campus-based institutions have increased in size, so have the institutional organizational requirements ‘solidified’. Without this structure it would become even more difficult to deliver consistent teaching services across the institution. Also such organizational consistency across institutions is necessary for purposes of accountability, accreditation, government funding, credit transfer, admission to graduate school, and a host of other reasons. Thus there are strong systemic reasons why these organizational requirements of face-to-face teaching are difficult if not impossible to change, at least at the institutional level.

Thus any teacher is faced by a number of massive constraints. In particular, the curriculum needs to fit within the time ‘units’ available, such as the length of the semester and the number of credits and contact hours for a particular course. The teaching has to take into account class size and classroom availability. Students (and teachers and instructors) have to be at specific places (classrooms, examination rooms, laboratories) at specific times.

Thus despite the concept of academic freedom, the structure of face-to-face teaching is to a large extent almost predetermined by institutional and organizational requirements. I am tempted to digress to question the suitability of such structural limitations for the needs of learners in a digital age, or to wonder whether faculty unions would accept such restrictions on academic freedom if they did not already exist, but the aim here is to identify which of these organizational constraints apply also to online learning, and which do not, because this will influence how we can structure teaching activities.

11.9.3 Institutional organizational requirements of online teaching

One obvious challenge for online learning, at least in its earliest days, was acceptance. There was (and still is) a lot of skepticism about the quality and effectiveness of online learning, especially from those that have never studied or taught online. So initially a lot of effort went into designing online learning with the same goals and structures as face-to-face teaching, to demonstrate that online teaching was ‘as good as’ face-to-face teaching (which, research suggests, it is).

However, this meant accepting the same course, credit and semester assumptions of face-to-face teaching. It should be noted though that as far back as 1971, the UK Open University opted for a degree program structure that was roughly equivalent in total study time to a regular, campus-based degree program, but which was nevertheless structured very differently, for instance, with full credit courses of 32 weeks’ study and half credit courses of 16 weeks’ study. One reason was to enable integrated, multi-disciplinary foundation courses. The Western Governors’ University, with its emphasis on competency-based learning, and Empire State College in New York State, with its emphasis on learning contracts for adult learners, are other examples of institutions that have different structures for teaching from the norm.

If online learning programs aim to be at least equivalent to face-to-face programs, then they are likely to adopt at least the minimum length of study for a program (e.g. four years for a bachelor’s degree in North America), the same number of total credits for a degree, and hence implicit in this is the same amount of study time as for face-to-face programs. Where the same structure begins to break down though is in calculating ‘contact time’, which by definition is usually the number of hours of classroom instruction. Thus a 13 week, 3 credit course is roughly equal to three hours a week of classroom time over one semester of 13 weeks.

There are lots of problems with this concept of ‘contact hours’, which nevertheless is the standard measuring unit for face-to-face teaching. Study at a post-secondary level, and particularly in universities, requires much more than just turning up to lectures. A common estimate is that for every hour of classroom time, students spend a minimum of another two hours on readings, assignments, etc. Contact hours vary enormously between disciplines, with usually arts/humanities having far less contact hours than engineering or science students, who spend a much larger proportion of time in labs. Another limitation of ‘contact hours’ is that it measures input, not output.

When we move to blended or hybrid learning, we may retain the same semester structure, but the ‘contact hour’ model starts to break down. Students may spend the equivalent of only one hour a week in class, and the rest online – or maybe 15 hours in labs one week, and none the rest of the semester.

A better principle would be to ensure that the students in blended, hybrid or fully online courses or programs work to the same academic standards as the face-to-face students, or rather, spend the equivalent ‘notional’ time on doing a course or getting a degree. This means structuring the courses or programs in such a way that students have the equivalent amount of work to do, whether it is online, blended or face-to-face. However, the way that work will be distributed can very considerably, depending on the mode of delivery.

11.9.4 How much work is an online course?

Before decisions can be made about the best way to structure a blended or an online course, some assumption needs to be made about how much time students should expect to study on the course. We have seen that this really needs to be equivalent to what a full-time student would study. However, just taking the equivalent number of contact hours for the face-to-face version doesn’t allow for all the other time face-to-face students spend studying.

A reasonable estimate is that a three credit undergraduate course is roughly equivalent to about 8-9 hours study a week, or a total of roughly 100 hours over 13 weeks. (A full-time student then taking 10 x 3 credits a year, with five 3 credit courses per semester, would be studying between 40-45 hours a week during the two semesters, or slightly less if the studying continued over the inter-semester period.).

Now this is my guideline. You don’t have to agree with it. You may think this is too much or too little for your subject. That doesn’t matter. You decide the time. The important point though is that you have a fairly specific target of total time that should be spent on a course or program by an average student, knowing that some will reach the same standard more quickly and others more slowly. This total student study time for a particular chunk of study such as a course or program provides a limit or constraint within which you must structure the learning. It is also a good idea to make it clear to students from the start how much time each week you are expecting them to work on the course.

Since there is far more content that could be put in a course than students will have time to study, this usually means choosing the minimum amount of content for the course for it to be academically sound, while still allowing students time for activities such as individual research, assignments or project work. In general, because instructors are experts in a subject and students are not, there is a tendency for instructors to underestimate the amount of work required by a student to cover a topic. Again, an instructional designer can be useful here, providing a second opinion on student workload.

11.9.5 Strong or loose structure?

Another critical decision is just how much you should structure the course for the students. This will depend partly on your preferred teaching philosophy and partly on the needs of the students.

If you have a strong view of the content that must be covered in a particular course, and the sequence in which it must be presented (or if you are given a mandated curriculum by an accrediting body), then you are likely to want to provide a very strong structure, with specific topics assigned for study at particular points in the course, with student work or activities tightly linked.

If on the other hand you believe it is part of the student’s responsibility to manage and organize their study, or if you want to give students some choice about what they study and the order in which they do it, so long as they meet the learning goals for the course, then you are likely to opt for a loose structure.

This decision should also be influenced by the type of students you are teaching. If students come without independent learning skills, or know nothing about the subject area, they will need a strong structure to guide their studies, at least initially. If on the other hand they are fourth year undergraduates or graduate students with a high degree of self-management, then a looser structure may be more suitable to their needs. Another determining factor will be the number of students in your class. With large numbers of students, a strong, well defined structure will be necessary to control your workload, as loose structures require more negotiation and support for individual students.

My preference is for a strong structure for fully online teaching, so students are clear about what they are expected to do, and when it has to be done by, even at graduate level. The difference is that with post-graduates, I will give them more choices of what to study, and longer periods to complete more complex assignments, but I will still define clearly the desired learning outcomes in terms of skill development in particular, such as research skills or analytical thinking, and provide clear deadlines for student work, otherwise I find my workload increases dramatically.

Blended learning provides an opportunity to enable students to gradually take more responsibility for their learning, but within a ‘safe’ structure of a regularly scheduled classroom event, where they have to report on any work they have been required to do on their own or in small groups. This means thinking not just at a course level but at a program level, especially for undergraduate programs. A good strategy would be to put a heavy emphasis on face-to-face teaching in the first year, and gradually introduce online learning through blended or hybrid classes in second and third year, with some fully online courses in the fourth year, thus preparing students better for lifelong learning.

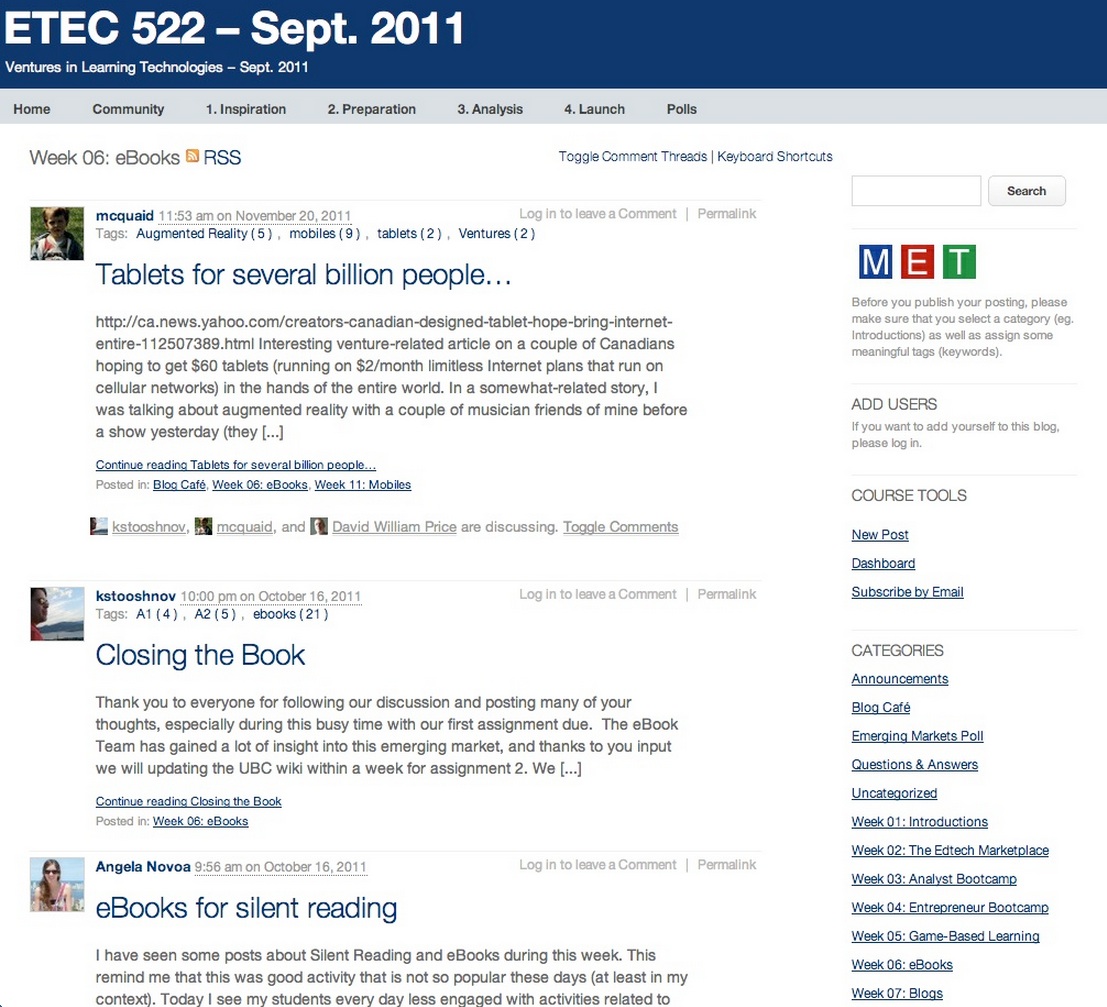

ETEC 522 is a loosely structured graduate program, in that students organize their own work around the course themes. The weekly topic structure is on the right, and the outcomes of student activities are in the main body, posted by students. Note this is not using a learning management system, but WordPress, a content management system, which allows students more easily to post and organize their activities.

11.9.6 Moving a face-to-face course online

This is the easiest way to determine the structure for an online course. The structure of the course will have already been decided to a large extent, in that the content of each week’s work is clearly defined by lecture topics. The main challenge will not be structuring the content but ensuring that students have adequate online activities (see later). Most learning management systems enable the course to be structured in units of one week, following the classroom topics. This provides a clear timetable for the students. This applies also to alternative approaches such as problem-based learning, where student activities may be broken down almost on a daily basis.

However, it is important to ensure that the face-to-face content is moved in a way that is suitable for online learning. For instance, Powerpoint slides may not fully represent what is covered in the verbal part of a lecture. This often means reorganizing or redesigning the content so that it is complete in an online version (your instructional designer should be able to help with this). At this point, you should look at the amount of work the online students will need to do in the set time period to make sure that with all the readings and activities it does not exceed the rough average weekly load you have set. It is at this point you may have to make some choices about either removing some content or activities, or making the work ‘optional.’ However, if optional it should not be assessed, and if it’s not assessed, students will quickly learn to avoid it. Doing this time analysis incidentally sometimes indicates that you’ve overloaded the face-to-face component as well.

It needs to be constantly in your mind that students studying online will almost certainly study in a more random manner than students attending classes on a regular basis. Instead of the discipline of being at a certain place at a certain time, online students still need clarity about what they are supposed to do each week or maybe over a longer time period as they move into later levels of study. What is essential is that students do not procrastinate online and hope to catch up towards the end of the course, which is often the main cause of failure in online courses (as in face-to-face classes).

We will see that defining clear activities for students is critical for success in online learning. We shall see when we discuss student activities below that there is often a trade-off to be made between content and activities if the student workload is to be kept to manageable proportions.

11.9.7 Structuring a blended learning course

Many blended learning courses are designed almost by accident, rather than deliberately. Online components, such as a learning management system to contain online learning materials, lecture notes or online readings, are gradually added to regular classroom teaching. There are obvious dangers in doing this if the face-to-face component is not adjusted at the same time. After a number of years, more and more materials, activities and work for students is added online, often optional but sometimes essential for assignments. Student workloads can increase dramatically as a result – and so too can the instructor’s, with more and more material to manage.

Rethinking a course for blended learning means thinking carefully about the structure and student workload. Means et al. (2011) hypothesised that one reason for better results from blended learning was due to students spending more time on task; in other words, they worked harder. This is good, but not if all their courses are adding more work. It is essential therefore when moving to a blended model to make sure that extra work online is compensated by less time in class (including travel time).

11.9.8 Designing a new online course or program

If you are offering a course or program that has not to date been offered on campus (for instance a professional or applied masters program) then you have much more scope for developing a unique structure that best fits the online environment and also the type of students that may take this kind of course (for example, working adults).

The important point here is that the way this time is divided up does not have to be the same as for a face-to-face class, because there is no organizational need for the student to be at a particular time or place in order to get the instruction. Usually an online course will be ‘ready’ and available for release to the students before the course officially begins. Students could in theory do the course more quickly or more slowly, if they wished. Thus the instructor has more options or choices about how to structure the course and in particular about how to control the student work flow.

This is particularly important if the course is being taken mainly by lifelong learners or part-time students, for instance. Indeed, it may be possible to structure a course in such a way that different students could work at different speeds. Competency-based learning means that students can work through the same course or program at very different speeds. Some open universities even have continuous enrolment, so they can start and finish at different times. Most students opting for an online course are likely to be working, so you may need to allow them longer to complete a course than full-time students. For instance, if on-campus masters programs need to be completed in one or two years, students may need up to five years to complete an online professional masters program.

11.9.9 Key principles in structuring a course

Now there may be good reasons for not doing some of these things, but this will be because of pedagogical rather than institutional organizational reasons. For instance, I’m not keen on continuous enrollment, or self-paced instruction, because especially at graduate level I make heavy use of online discussion forums and online group work. I like students to work through a course at roughly the same pace, because it leads to more focused discussions, and organizing group work when students are at different points in the course is difficult if not impossible. However, in other courses, for instance a math course, self-paced instruction may make a lot of sense. I will discuss other non-traditional course structures when we discuss student activities below.

However you structure the course, though, two basic principles remain:

- there must be some notional idea of how much time students should spend each week on the course;

- students should be clear each week about what they have to do and when it needs to be done.

11.9.10 Designing student activities

This is the most critical part of the design process, especially but not just only for fully online students, who have neither the regular classroom structure or campus environment for contact with the instructor and other students nor the opportunity for spontaneous questions and discussions in a face-to-face class. Regular student activities though are critical for keeping all students engaged and on task, irrespective of mode of delivery.

These can include:

- assigned readings;

- simple multiple choice self-assessment tests of understanding with automated feedback, using the computer-based testing facility within a learning management system;

- questions regarding short paragraph answers which may be shared with other students for comparison or discussion;

- formally marked and assessed monthly assignments in the form of short essays;

- individual or group project work spaced over several weeks;

- an individual student blog or e-portfolio that enables the student to reflect on their recent learning, and which may be shared with the instructor or other students;

- online discussion forums, which the instructor will need to organize and monitor.

There are many other activities that instructors can devise to keep students engaged. However, all such activities need to be clearly linked to the stated learning outcomes for the course and can be seen by students as helping them prepare for any formal assessment. If learning outcomes are focused on skills development, then the activities should be designed to give students opportunities to develop or practice such skills.

These activities also need to be regularly spaced and an estimate made of the time students will need to complete the activities. In step eight, we shall see that student engagement in such activities will need to be monitored by the instructor.

It is at this point where some hard decisions may need to be made about the balance between ‘content’ and ‘activities’. Students must have enough time to do regular activities (other than just reading) once each week at least, or their risk of dropping out or failing the course will increase dramatically. In particular they will need some way of getting feedback or comments on their activities, either from the instructor or from other students, so the design of the course will have to take account of the instructors’ workload as well as the students’.

In my view, most university and college courses are overstuffed with content and not enough consideration is given to what students need to do to absorb, apply and evaluate such content. I have a very rough rule of thumb that students should spend no more than half their time reading content and attending lectures, the rest being spent on interpreting, analyzing, or applying that content through the kinds of activities listed above. As students become more mature and more self-managed the proportion of time spent on activities can increase, with the students themselves being responsible for identifying appropriate content that will enable them to meet the goals and criteria laid down by the instructor. However, that is my personal view. Whatever your teaching philosophy though, there must be plenty of activities with some form of feedback for online students, or they will drop like flies on a cold winter’s day.

11.9.11 Many structures, one high standard

There are many other ways to ensure an appropriate structure for an online course. For instance, the Carnegie Mellon Open Learning Initiative provides a complete course ‘in a box’ for standard first and second year courses in two year colleges. These include a learning management system site with content, objectives and activities pre-loaded, with an accompanying textbook. The content is carefully structured, with in-built student activities. The instructors’ role is mainly delivery, providing student feedback and marking where needed. These courses have proved to be very effective, in that most students successfully complete such programs.

The History instructor in Scenario J kept a normal three lectures a week structure for the first three weeks, then students worked entirely online in small groups on a major project for five weeks, then returned to class for one three-hour session a week for five weeks for students to report back on and discuss their projects as a whole class group.

We saw that in competency-based learning, students can work at their own speed through highly structured courses academically, in terms of topic sequences and learner activities, that nevertheless have flexibility in the time students can take to successfully complete a competency.

The Integrated Science Program at McMaster University is built around 6-10 week undergraduate research projects.

cMOOC’s such as Stephen Downes, George Siemen’s, and Dave Cormier’s #Change 11 have a loose structure, with different topics with different contributors each week, but student activities, such as blog posts or comments, are not organized by the course designers but left to the students. However, these are not credit courses, and few students work all the way through the whole MOOC, and that is not their intent. The Stanford and MIT xMOOC’s on the other hand are highly structured, with student activities, and the feedback is fully automated. Less than 10 per cent of students who start these MOOCs successfully complete them, but they too are non-credit courses. Increasingly MOOCs are becoming shorter, some of as little as three or four weeks in length.

Online learning enables teachers and instructors to break away from a rigid three semester, 13 week, three lectures a week structure, and build courses around structures that best meet the needs of learners and the preferred teaching method of the teacher or instructor. My aim in a credit course or program is to ensure high academic quality and high completion rates. For me that means developing an appropriate structure and related learning activities as a key step in achieving quality in credit online courses.

Activity 11.9 Structuring your course or program

1. How many hours a week should a typical student spend studying a three credit course? If your answer differs from mine (8-9 hours), why?

2. If you were designing an online credit program from scratch, would you need to follow a ‘traditional’ structure of three credits over 13 weeks? If not, how would you structure such a program, and why?

3. Do you think most credit courses are ‘overstuffed’ with content and do not have enough learning activities? Do we focus too much on content and not enough on skills development in higher education? How does that affect the structure of courses? How much does it affect the quality of the learning?