Chapter 2: The nature of knowledge and the implications for teaching

2.3 Objectivism and behaviourism

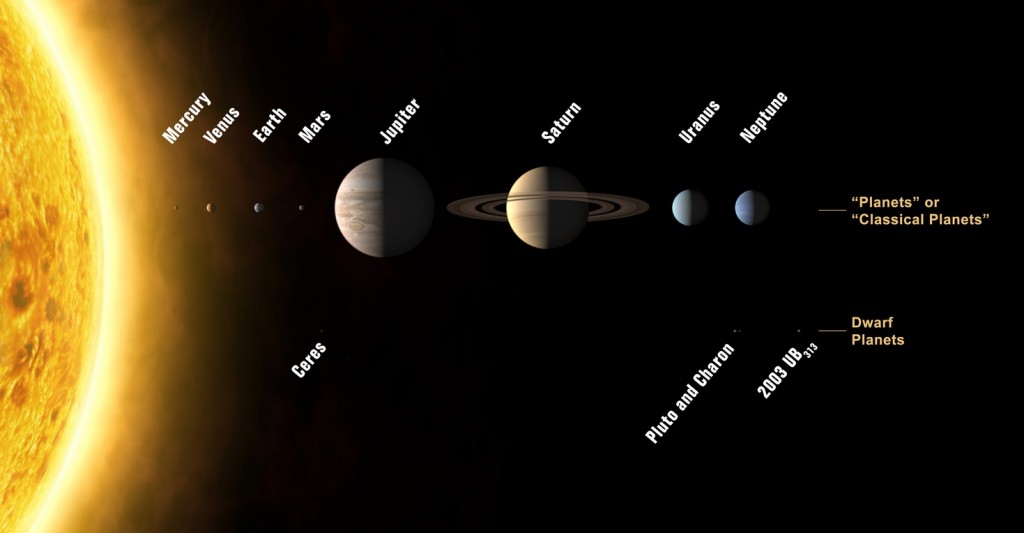

Image: © International Astronomical Union/Wikipedia

2.3.1 The objectivist epistemology

Objectivists believe that there exists an objective and reliable set of facts, principles and theories that either have been discovered and delineated or will be over the course of time. This position is linked to the belief that truth exists outside the human mind, or independently of what an individual may or may not believe. Thus the laws of physics are constant, although our knowledge of them may evolve as we discover the ‘truth’ out there.

2.3.2 Objectivist approaches to teaching

A teacher operating from a primarily objectivist view is more likely to believe that a course must present a body of knowledge to be learned. This may consist of facts, formulas, terminology, principles, theories and the like.

The effective transmission of this body of knowledge becomes of central importance. Lectures and textbooks must be authoritative, informative, organized, and clear. The student’s responsibility is accurately to comprehend, reproduce and add to the knowledge handed down to him or her, within the guiding epistemological framework of the discipline, based on empirical evidence and the testing of hypotheses. Course assignments and exams would require students to find ‘right answers’ and justify them. Original or creative thinking must still operate within the standards of an objectivist approach – in other words, new knowledge development must meet the rigorous standards of empirical testing within agreed theoretical frameworks.

An ‘objectivist’ teacher has to be very much in control of what and how students learn, choosing what is important to learn, the sequence, the learning activities, and how learners are to be assessed.

2.3.3 Behaviourism

Although initially developed in the 1920s, behaviourism still dominates approaches to teaching and learning in many places, particularly in the USA. Behaviourist psychology is an attempt to model the study of human behaviour on the methods of the physical sciences, and therefore concentrates attention on those aspects of behaviour that are capable of direct observation and measurement. At the heart of behaviourism is the idea that certain behavioural responses become associated in a mechanistic and invariant way with specific stimuli. Thus a certain stimulus will evoke a particular response. At its simplest, it may be a purely physiological reflex action, like the contraction of an iris in the eye when stimulated by bright light.

However, most human behaviour is more complex. Nevertheless behaviourists have demonstrated in labs that it is possible to reinforce through reward or punishment the association between any particular stimulus or event and a particular behavioural response. The bond formed between a stimulus and response will depend on the existence of an appropriate means of reinforcement at the time of association between stimulus and response. This depends on random behaviour (trial and error) being appropriately reinforced as it occurs.

This is essentially the concept of operant conditioning, a principle most clearly developed by Skinner (1968). He showed that pigeons could be trained in quite complex behaviour by rewarding particular, desired responses that might initially occur at random, with appropriate stimuli, such as the provision of food pellets. He also found that a chain of responses could be developed, without the need for intervening stimuli to be present, thus linking an initially remote stimulus with a more complex behaviour. Furthermore, inappropriate or previously learned behaviour could be extinguished by withdrawing reinforcement. Reinforcement in humans can be quite simple, such as immediate feedback for an activity or getting a correct answer to a multiple-choice test.

Click on image to see video

You can see a fascinating five minute film of B.F. Skinner describing his teaching machine in a 1954 film captured on YouTube, either by clicking on the picture above or at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jTH3ob1IRFo

Underlying a behaviourist approach to teaching is the belief that learning is governed by invariant principles, and these principles are independent of conscious control on the part of the learner. Behaviourists attempt to maintain a high degree of objectivity in the way they view human activity, and they generally reject reference to unmeasurable states, such as feelings, attitudes, and consciousness. Human behaviour is above all seen as predictable and controllable. Behaviourism thus stems from a strongly objectivist epistemological position.

Skinner’s theory of learning provides the underlying theoretical basis for the development of teaching machines, measurable learning objectives, computer-assisted instruction, and multiple choice tests. Behaviourism’s influence is still strong in corporate and military training, and in some areas of science, engineering, and medical training. It can be of particular value for rote learning of facts or standard procedures such as multiplication tables, for dealing with children or adults with limited cognitive ability due to brain disorders, or for compliance with industrial or business standards or processes that are invariant and do not require individual judgement.

Behaviourism, with its emphasis on rewards and punishment as drivers of learning, and on pre-defined and measurable outcomes, is the basis of populist conceptions of learning among many parents, politicians, and, it should be noted, computer scientists interested in automating learning. It is not surprising then that there has also been a tendency until recently to see technology, and in particular computer-aided instruction, as being closely associated with behaviourist approaches to learning, although we shall see in Chapter 5, Section 4 that computers do not necessarily have to be used in a behaviourist way.

Lastly, although behaviourism is an ‘objectivist’ approach to teaching, it is not the only way of teaching ‘objectively’. For instance, problem-based learning can still take a highly objective approach to knowledge and learning.

Activity 2.3 Defining the limits of behaviourism

1. What areas of knowledge do you think would be best ‘taught’ or learned through a behaviourist approach?

2. What areas of knowledge do you think would NOT be appropriately taught through a behaviourist approach?

3. What are your reasons?

References

Skinner, B. (1968) The Technology of Teaching, 1968. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts