Chapter 1: Fundamental Change in Education

1.1 Structural changes in the economy: the growth of a knowledge society

Image: © CC Duncan Campbell, 2012

1.1.1 The digital age

In a digital age, we are surrounded, indeed, immersed, in technology. Furthermore, the rate of technological change shows no sign of slowing down. Technology is leading to massive changes in the economy, in the way we communicate and relate to each other, and increasingly in the way we learn. Yet our educational institutions were built largely for another age, based around an industrial rather than a digital era.

Thus teachers and instructors are faced with a massive challenge of change. How can we ensure that we are developing the kinds of graduates from our courses and programs that are fit for an increasingly volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous future? What should we continue to protect in our teaching methods (and institutions), and what needs to change?

To answer these questions, this book:

- discusses the main changes that are leading to a re-examination of teaching and learning

- identifies different understandings of knowledge and the different teaching methods associated with these understandings

- analyses the key characteristics of technologies with regard to teaching and learning

- recommends strategies for choosing between media and technologies

- recommends strategies for high quality teaching in a digital age.

In this chapter I set out some of the main developments that are forcing a reconsideration of how we should be teaching.

1.1.2 The changing nature of work

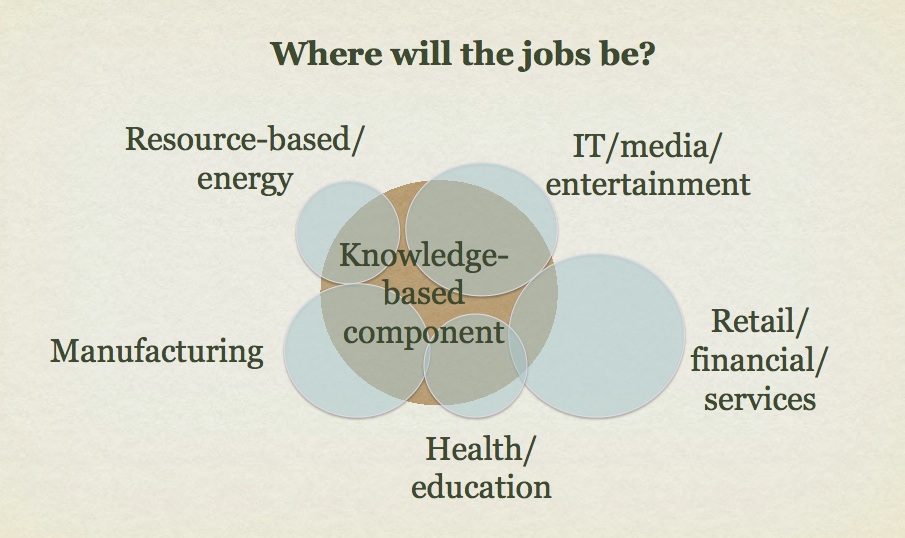

Of the many challenges that institutions face, one is in essence a good one, and that is increased demand, particularly for post-secondary education. Figure 1.1.2 below represents the extent to which knowledge has become an increasingly important element of economic development, and above all in job creation.

![]()

The figure is symbolic rather than literal. The pale blue circles representing the whole work force in each employment sector may be larger or smaller, depending on the country, as too will be the proportion of knowledge workers in that industry, but at least in developed countries and also increasingly in economically emerging countries, the knowledge component is growing rapidly: more brains and less brawn are required (see OECD, 2013a). Economically, competitive advantage goes increasingly to those companies and industries that can leverage gains in knowledge (OECD, 2013b). Indeed, knowledge workers often create their own jobs, starting up companies to provide new services or products that did not exist before they graduated.

From a teaching perspective the biggest impact is likely to be on technical and vocational instructors and students, where the knowledge component of formerly mainly manual skills is expanding rapidly. Particularly in the trades areas, plumbers, welders, electricians, car mechanics and other trade-related workers are needing to be problem-solvers, IT specialists and increasingly self-employed business people, as well as having the manual skills associated with their profession.

Another consequence of the growth in knowledge-based work is the need for more people with higher levels of education than previously, resulting in a demand for more highly qualified workers at a university level. However, even at a university level, the type of knowledge and skills required of graduates is also changing.

1.1.3 Knowledge-based workers

There are certain common features of knowledge-based workers in a digital age:

- they usually work in small companies (less than 10 people);

- they sometimes own their own business, or are their own boss; sometimes they have created their own job, which didn’t exist until they worked out there was a need and they could meet that need;

- they often work on contract or are self-employed, so they move around from one job to another fairly frequently;

- the nature of their work tends to change over time, in response to market and technological developments and thus the knowledge base of their work tends to change rapidly;

- they are digitally smart or at least competent digitally; digital technology is often a key component of their work;

- because they often work for themselves or in small companies, they play many roles: marketer, designer, salesperson, accountant/business manager, technical support, for example;

- they depend heavily on informal social networks to bring in business and to keep up to date with current trends in their area of work;

- they need to keep on learning to stay on top in their work, and they need to manage that learning for themselves;

- above all, they need to be flexible, to adapt to rapidly changing conditions around them.

It can be seen then that it is difficult to predict with any accuracy what many graduates will actually be doing ten or so years after graduation, except in very broad terms. Even in areas where there are clear professional tracks, such as medicine, nursing or engineering, the knowledge base and even the working conditions are likely to undergo rapid change and transformation over that period of time. However, we shall see in Section 1.2 that it is possible to predict many of the skills they will need to survive and prosper in such an environment.

This is good news for the higher education sector overall as the knowledge and skill levels needed in the workforce increases. It has resulted in a major expansion of higher education to meet the demand for knowledge-based work and higher levels of skill. The province of Ontario in Canada for instance already has a participation rate of almost 60 per cent of high school leavers going on to some form of post-secondary education, and the provincial government wants to increase that participation rate to 70 per cent, partly to offset the loss of more traditional manufacturing jobs in the province (Ontario, 2012). This means more students for universities and colleges.

Activity 1.1 Thinking about skills

1. What kind of jobs are graduates in your subject discipline likely to get? Can you describe the kinds of skills they are likely to need in such a job? To what extent has the knowledge and skills component of such work changed over the last 20 years?

2. Look at the family members and friends outside your academic or educational field. What kind of knowledge and skills do they need now that they didn’t need when they were at school or college – or even 20 years ago in the same work area? (You may need to ask them this!)

References

OECD (2013a) OECD Skills Outlook: First Results from the Survey of Adult Skills Paris: OECD

OECD (2013b) Competition Policy and Knowledge-Based Capital Paris: OECD

Ontario (2012) Strengthening Ontario’s Centres of Creativity, Innovation and Knowledge Toronto ON: Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities