Chapter 17. Government and Politics

17.1 Power and Authority

The nature of political control — what sociologists define as power and authority — is an important part of society.

Sociologists have a distinctive approach to studying governmental power and authority that differs from the perspective of political scientists. For the most part, political scientists focus on studying how power is distributed in different types of political systems. They would observe, for example, that the Canadian political system is a constitutional monarchy divided into three distinct branches of government (legislative, executive, and judicial), and might explore how public opinion affects political parties, elections, and the political process in general. Sociologists, however, tend to be more interested in government more generally; that is, the various means and strategies used to direct or conduct the behaviour and actions of others (or of oneself). As Michel Foucault described it, government is the “conduct of conduct,” the way some seek to act upon the conduct of others to change or channel that conduct in a certain direction (Foucault 1982, pp. 220–221). Government is not so much a specific institution, but the process of governing exercised in various sites throughout society.

Government implies that there are relations of power between rulers and ruled, but the context of rule is not limited to the state. Government in this sense is in operation whether the power relationship is between states and citizens, institutions and clients, parents and children, doctors and patients, employers and employees, masters and dogs, or even oneself and oneself. Think of the training regimes, studying routines, or diets people put themselves through as they seek to change or direct their lives in a particular way. These are exercises of self-government. The role of the state and its influence on society (and vice versa) is just one aspect of governmental relationships.

On the other side of governmental power and authority are the various forms of resistance to being ruled. Foucault (1982) argues that without this latitude for resistance or independent action on the part of the one over whom power is exercised, there is no relationship of power or government. There is only a relationship of violence or force. One central question sociological analysis asks therefore is: Why do people obey, especially in situations when it is not in their objective interests to do so? “Why do men fight for their servitude as stubbornly as though it were their salvation?” as Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari once put it (Deleuze and Guattari 1977). This entails a more detailed study of what is meant by power.

Making Connections: Social Policy and Debate

Neoliberalism as Style of Government

Neoliberalism is fascinating sociologically because, aside from being a type of economic policy (see Chapter 4. Society and Modern Life), it signals a new way of governing individuals. This has broad implications outside of the narrow parameters of neoliberal policies like tax cuts, deregulation, and reducing the state’s role in the economy. Neoliberalism also refers to a more general strategy of governing individual conduct in several different areas including health, employment, education, security, and crime control. In an interesting way, it governs individuals through their exercise of freedom and free choice. Whereas the welfare state was frequently criticized by neoliberals for fostering a culture of welfare dependency and a “one size fits all” concept of government services, the new types of neoliberal strategies emphasize various ways to create active and independent entrepreneurial citizens (Rose, 1999). Thus, the idea of markets is important because markets are mechanisms that regulate and discipline people through the free choices that they make. If they make good choices they profit; if they make bad choices they pay.

One thing the “neo” (or “new”) in neo-liberalism signifies is the extension of the idea of the market into areas of life where no markets existed before. For example, the provision of care for people with disabilities used to be provided through state institutionalization. Today, it is common to find a model of care like “individualized funding” (See, for example, Community Living BC, 2013). The state provides families of people with disabilities with direct payments that they use to pay for care providers who they choose after doing their own research on appropriate therapies or treatments. A market for caregivers and therapists is created, based on an assumption that this it is a more efficient model for matching the skills of care contractors with the needs of people with disabilities. Rather than care being provided as needed, individuals or families are encouraged or obliged to become active consumers of therapeutic services and to make calculative decisions from an array of market choices. The families need to demonstrate their competent use of the money through formal mechanisms like budgets, audits, targets, minimal standards, and contracts but otherwise are free to choose the services they want.

In practice these policies are often means to further reduce the overall amount of state expenditure for people with disabilities and their families, but as a method for governing the lives of individuals, they represent a fundamental shift from the notion of individuals as citizens with rights to individuals as agents who must independently exercise free choice, enterprise, and self-responsibility. Even though these types of policies, when properly funded, have positive features for those with the wherewithal to take advantage of the expansion of choice (Sandborn, 2012), they represent a significant shift in the strategies of government by downloading risks and responsibilities onto individuals. Thus, neoliberalism is both a macro-level economic policy, but it is also a strategy designed to change the type of relationship people have with themselves and the concept of themselves as citizens.

What Is Power?

For centuries, philosophers, politicians, and social scientists have explored and commented on the nature of power. Pittacus (c. 640–568 BCE) opined, “The measure of a man is what he does with power,” and Lord Acton perhaps more famously asserted, “Power tends to corrupt; absolute power corrupts absolutely” (1887). Indeed, the concept of power can have decidedly negative connotations, and the term itself is difficult to define. There are at least two definitions of power, which are designated below as power (1) and power (2).

As noted above, power relationships refer in general to a kind of strategic relationship between rulers and the ruled: a set of practices by which states seek to govern the life of their citizens, managers seek to control the labour of their workers, parents seek to guide and raise their children, dog owners seek to train their dogs, doctors seek to manage the health of their patients, chess players seek to control the moves of their opponents, individuals seek to keep their own lives in order, etc. These practices are strategic in the sense that they anticipate resistance on the part of the governed and therefore plan various ways to overcome resistance to achieve their goals.

Many of these sites of the exercise of power fall outside our normal understanding of power because they do not seem “political” — they do not address fundamental questions or disagreements about a “whole way of life” — and because the relationships between power and resistance in them can be very fluid. There is a give and take between the attempts of the rulers to direct the behaviour of the ruled and the attempts of the ruled to resist those directions. In many cases, it is difficult to see relationships as power relationships at all unless they become fixed or authoritarian. This is because the conventional understanding of power is that one person or one group of people has power over another. In other words, when people think about somebody, some group, or some institution having power over them, they are thinking about a relation of domination.

Max Weber defined power (1) as “the chance of a man or of a number of men to realize their own will in a communal action even against the resistance of others who are participating in the action” (Weber 1919a). It is the varying degrees of ability a person or persons have to exercise their will over others. When these “chances” become structured as forms of domination, the give and take between power and resistance is fixed into more or less permanent hierarchical arrangements. They become institutionalized. As such, power affects more than personal relationships; it shapes larger dynamics like social groups, professional organizations, and governments. Similarly, a government’s power is not necessarily limited to control of its own citizens. A dominant nation, for instance, will often use its power to influence or support other governments or to seize control of other nation states. Efforts by the Canadian government to wield power in other countries have included joining with other nations to form the Allied forces during World Wars I and II, entering Afghanistan in 2001 with the NATO mission to topple the Taliban regime, and imposing sanctions on the government of Russia in the hopes of constraining its invasion of Ukraine.

Endeavours to gain power and influence do not necessarily lead to domination, violence, exploitation, or abuse. Leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi, for example, commanded powerful movements that affected positive change without military force. Both men organized nonviolent protests to combat corruption and injustice and succeeded in inspiring major reform. They relied on a variety of nonviolent protest strategies such as rallies, sit-ins, marches, petitions, and boycotts.

It is therefore important to retain the distinction between domination and power. Politics and power are not “things” that are exclusively properties of the state or properties of an individual, ruling class, or group. At a more basic level, power (2) is a capacity or ability that each person has to create and act, individually or collectively. It is a power of action. As a result, power and politics must also be understood as the collective capacities people have to create and build new forms of community or “commons” (Negri, 2004). Power in this sense is the power one thinks of when people speak of an ability to do or create something — a potential. Just as a carpenter has the potential to build a house, people have the ability to build community and collectively accomplish goals. It is the way in which people collectively give form to the communities that they live in, whether at a very local level or a global level. Power establishes the things that people can do and the things that people cannot do.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle’s original notion of politics is the idea of a freedom people grant themselves to rule themselves (Aristotle, 1908). Therefore, power is not in principle domination. It is the give and take people experience in everyday life as they come together to construct a better community — a “good life” as Aristotle put it. When Deleuze and Guattari (1977) ask why people obey even when it is not in their best interests, they are asking about the conditions in which power is exercised as domination. Thus, the critical task of sociology is to ask how people might free themselves from the constraints of domination to engage more actively and freely in the creation of community.

Making Connections: Big Picture

Did Facebook and Twitter Cause the Arab Spring?

Recent movements and protests that were organized to reform governments and install democratic ideals in North African and the Middle East have been collectively labelled “Arab Spring” by journalists. In describing the dramatic reform and protests in these regions, journalists have noted the use of internet platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, some even implying that this technology has been instrumental in spurring these reforms. In states with a strong capacity for media censorship, social sites provided an opportunity for citizens to circumvent authoritarian restrictions (Zuckerman, 2011).

As social movement activists in North Africa used the internet to communicate, it provided them with an invaluable tool: anonymity. John Pollock (2011), in an authoritative analysis published in MIT’s Technology Review, gave readers an intriguing introduction to two transformative revolutionaries named “Foetus” and “Waterman,” who are leaders in the Tunisian rebel group Takriz. Both men relied heavily on the internet to communicate and even went as far as to call it the “GPS” (Global Positioning System) for the revolution (Pollock, 2011). Before the internet, meetings of protestors led by dissidents like Foetus and Waterman often required participants to assemble in person, placing them at risk of being raided by government officials. Thus, leaders would more likely have been jailed, tortured — and perhaps even killed — before movements could gain momentum.

The internet also enabled widespread publicity about the atrocities being committed in the Arab region. The fatal beating of Khaled Said, a young Egyptian computer programmer, provides a prime example. Said, who possessed videos highlighting acts of police corruption in Egypt, was brutally killed by law enforcement officers in the streets of Alexandria. After Said’s beating, Said’s brother used his cell phone to capture photos of his brother’s grisly corpse and uploaded them to Facebook. The photos were then used to start a protest group called “We Are All Khaled Said,” which now has more than a million members (Pollock, 2011). Numerous other videos and images, similarly appalling, were posted on social media sites to build awareness and incite activism among local citizens and the larger global community.

Of course, the internet has also been used by states and other powerful actors to spread disinformation and propaganda and to undermine resistance movements. During the Arab Spring, authoritarian states seemed unprepared to respond to the effective use of social media by social media activists. But Pollock (2017) reports on the increasing “weaponization of information” by state actors. For example, following the shooting down of the Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 over Ukraine by Russian anti-aircraft missiles in 2014, the Russian response was to use social media to deny responsibility and to invent and circulate counternarratives. “Russia’s tactics … rely on … ‘the 4D approach’: ‘Dismiss, distort, distract, dismay. Never confess, never admit—just keep on attacking.’ …. Critics are besmirched, sometimes in an official announcement, sometimes through proxies, sometimes through anonymous sources quoted in state media; then paid trolls and highly automated networks of bots add scale” (Pollock, 2017). Social media platforms are increasingly used in this way to weaponize information and circulate misinformation as a way to neutralize processes of democratic will formation.

Politics and the State

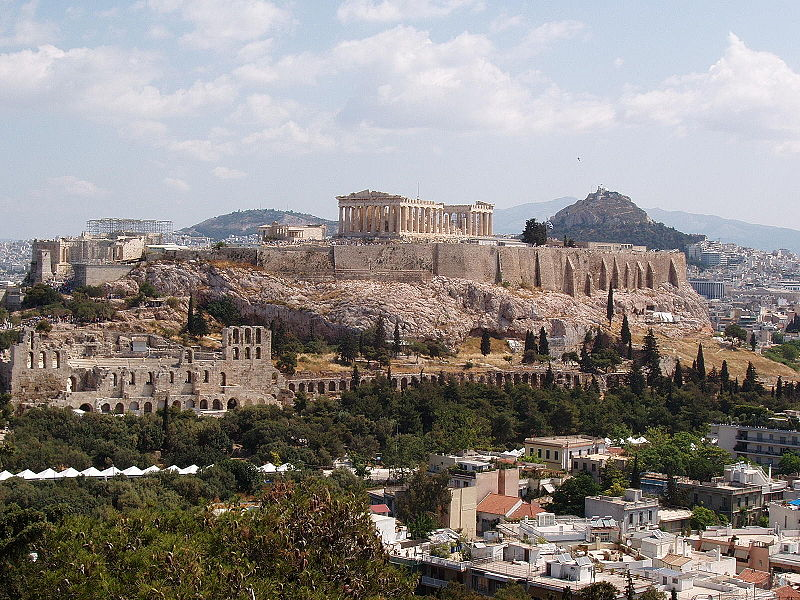

What is politics? What is political? The words politics and political refer back to the ancient Greek polis or city-state. For the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BCE), the polis was the ideal political form that collective life took. Political life was life oriented toward the “good life” or toward the collective achievement of noble qualities. The term “politics” referred simply to matters of concern to the running of the polis.

Behind Aristotle’s idea of the polis is the concept of an autonomous, self-contained community in which people rule themselves. The people of the polis take it upon themselves to collectively create a way of living together that is conducive to the achievement of human aspirations and good life. Similar to the definition of power, there are at least two definitions of politics, which are designated below as politics (1) and politics (2).

Politics (1) is the means by which form is given to the life of a people. Citizens give themselves the responsibility to create the conditions in which the good life can be achieved. For Aristotle, this meant that there was an ideal size for a polis, which he defined as the number of people that could be taken in a single glance (Aristotle 1908). The city-state was for him therefore the ideal form for political life in ancient Greece.

Today people think of the nation-state as the form of modern political life. A nation-state is a political unit whose boundaries are co-extensive with a society, that is, with a cultural, linguistic, or ethnic nation. Politics is the sphere of activity involved in running the state. As Max Weber defines it, politics (2) is the activity of “striving to share power or striving to influence the distribution of power, either among states or among groups within a state” (Weber 1919b). This might be too narrow a way to think about politics, however, because it often makes it appear that politics is something that only happens far away in “the state.” It is a way of giving form to politics that takes control out of the hands of people.

Max Weber: Classical definitions of politics and the state

“A ‘ruling organization’ will be called ‘political’ in so far as its existence and order is continuously safeguarded within a given territorial area by the threat and application of physical force on the part of the administrative staff. A compulsory political organization with continuous operations will be called a ‘state’ in so far as administrative staff successfully upholds the claim to the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force in the enforcement of its order. Social action, especially organized action, will be spoken of as ‘politically oriented’ if it aims at exerting influence on the government of a political organization; especially at the appropriation, expropriation, redistribution or allocation of powers of government” (Weber 1978).

In fact, the modern nation-state is a relatively recent political form. Foraging societies had no formal state institution, and prior to the modern age, feudal Europe was divided into a complex patchwork of small overlapping jurisdictions. Feudal secular authority was often at odds with religious authority. It was not until the Peace of Westphalia (1648) at the end of the Thirty Years War that the modern nation-state system can be said to have come into existence. Even then, Germany, for example, did not become a unified state until 1871. Prior to 1867, most of the colonized territory that became Canada was owned by one of the earliest corporations: the Hudson’s Bay Company. It was not governed by a state at all. If politics is the means by which form is given to the life of a people, then it is clear that this is a type of activity that has varied throughout history. Politics is not exclusively about the state or a property of the state. The question is, why do people come to think that it is?

The modern state is based on the principle of sovereignty and the sovereign state system. Sovereignty is the political form in which a single, central “sovereign” or supreme lawmaking authority governs within a clearly demarcated territory. The sovereign state system is the structure by which the world is divided up into separate and indivisible sovereign territories. At present there are 193 member states in the United Nations (United Nations, 2013). The entire globe is thereby divided up into separate states except for the oceans and Antarctica.

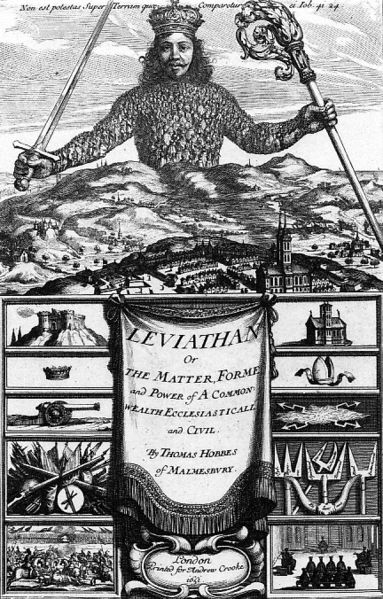

Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) is the early modern English political philosopher whose Leviathan (1651) established modern thought on the nature of sovereignty. Hobbes argued that social order, or what sociologists would call today “society” — “peaceable, sociable and comfortable living” (Hobbes 1651) — depended on an unspoken contract between the citizens and the “sovereign” or ruler. In this contract, individuals give up their natural rights to use violence to protect themselves and further their interests and cede them to a sovereign. In exchange, the sovereign provides law and security for all (i.e., for the “commonwealth”). For Hobbes, there could be no society in the absence of a sovereign power that stands above individuals to “over-awe them all” (Hobbes, 1651). Life would otherwise be in a “state of nature” or a state of “war of everyone against everyone.” People would live in “continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man [would be] solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

It is worthwhile to examine these premises, however, because they continue to structure contemporary political life even if the absolute rule of monarchs has been replaced by the democratic rule of the people in many states. (An absolute monarchy is a government wherein a monarch has absolute or unmitigated power). The implication of Hobbes’s analysis is that the people must acquiesce to the absolute power of a single sovereign or sovereign assembly, which, in turn, cannot ultimately be held to any standard of justice or morality outside of its own guarantee of order. Who or what would have the power to enforce that standard? Therefore, democracy always exists in a state of tension with the authority of the sovereign state. Similarly, while order is maintained by “the sovereign” within the sovereign state, outside the state or between states there is no sovereign to “over-awe them all.” The international sovereign state system is always potentially in a state of war of all against all. It offered a neat solution to the problem of confused and overlapping political jurisdictions in medieval Europe, but is itself inherently unstable (Walker, 1993).

Hobbes’ definition of sovereignty is also the context of Max Weber’s definition of the state. Weber defines the state, not as an institution or decision-making body, but as “a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory” (Weber 1919b). Weber’s definition emphasizes the way in which the state is founded on the control of territory through the use of force. In his lecture “Politics as a Vocation,” he argues, “The decisive means for politics is violence” (Weber 1919b). However, as noted above, power is not always exercised through the use of force. Nor would a modern sociologist accept that it is conferred through a mysterious “contract” with the sovereign, as Hobbes argued. Therefore, why do people submit to rule? “When and why do men obey?” (Weber 1919b). Weber’s answer is based on a distinction between the concepts of power and authority.

Types of Authority

The protesters in Tunisia and the civil rights protesters of Mahatma Gandhi’s day had influence apart from their position in a government. Their influence came, in part, from their ability to advocate for what many people held as important values. Government leaders might have this kind of influence as well, but they also have the advantage of wielding power associated with their position in the government. As this example indicates, there is more than one type of authority in a community.

If Weber defined power as the ability to achieve desired ends despite the resistance of others (Weber, 1919a), authority is when power or domination is perceived to be legitimate or justified rather than coercive. Authority refers to accepted power — that is, power that people agree to follow. People listen to authority figures because they feel that these individuals are worthy of respect. Generally speaking, people perceive the objectives and demands of an authority figure as reasonable and beneficial, or true.

A citizen’s interaction with a police officer is a good example of how people react to authority in everyday life. For instance, a person who sees the flashing red and blue lights of a police car in their rearview mirror usually pulls to the side of the road without hesitation. Such a driver most likely assumes that the police officer behind him serves as a legitimate source of authority and has the right to pull a driver over. As part of the officer’s official duties, they have the power to issue a speeding ticket if the driver was driving too fast. If the same officer, however, were to command the driver to follow the police car home and mow their lawn, the driver would likely protest that the officer does not have the authority to make such a request.

Not all authority figures are police officers or elected officials or government authorities. Besides formal offices, authority can arise from tradition and personal qualities. Max Weber realized this when he examined individual action as it relates to authority, as well as large-scale structures of authority and how they relate to a society’s economy. Based on this work, Weber developed a classification system for authority. His three types of authority are traditional authority, charismatic authority, and rational-legal authority (Weber 1922).

| Traditional | Charismatic | Rational-Legal | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source of authority | Legitimized by long-standing custom | Based on a leader’s personal qualities | Authority resides in the office, not the person |

| Authority Figure/Figures | Patriarch | Dynamic personality | Bureaucratic officials |

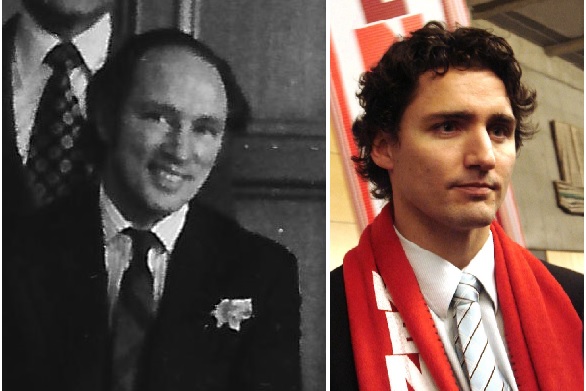

| Examples | Patrimonialism (traditional positions of authority) | Jesus Christ, Hitler, Martin Luther King, Jr., Pierre Trudeau | Parliament, Civil Service, Judiciary |

Traditional authority is usually understood in the context of premodern power relationships. According to Weber, the power of traditional authority is accepted because that has traditionally been the case; its legitimacy exists because it has been accepted for a long time. People obey their lord, church, or parent because it is customary to do so. The authority of the aristocracy or the church is conferred on them through tradition, or the “authority of the ‘eternal yesterday’” (Weber 1919b). Britain’s Queen Elizabeth, for instance, occupies a position that she inherited based on the traditional rules of succession for the monarchy, a form of government in which a single person, or monarch, rules until that individual dies or abdicates the throne. People adhere to traditional authority because they are invested in the past and feel obligated to perpetuate it. However, in modern society it would also be fair to say that obedience through tradition is in large part a function of a customary or “habitual orientation to conform,” in that people do not generally question or think about the power relationships in which they participate. It is just “the way things are done.”

For Weber, modern authority is better understood to oscillate between the latter two types of legitimacy: rational-legal and charismatic authority. On one hand, as he puts it, “organized domination” relies on “continuous administration” (Weber, 1919) and in particular, the rule-bound form of administration known as bureaucracy. Power made legitimate by laws, written rules, and regulations is termed rational-legal authority. In this type of authority, power is vested in a particular system, not in the person implementing the system. However irritating bureaucracy might be, people generally accept its legitimacy because they have the expectation that its processes are conducted in a neutral, disinterested fashion, according to explicit, written rules and laws. Rational-legal types of rule have authority because they are rational; that is, they are unbiased, predictable, and efficient.

On the other hand, people also obey because of the charismatic personal qualities of a leader. In this respect, it is not so much a question of obeying as following. Weber saw charismatic leadership as a kind of antidote to the machine-like rationality of bureaucratic mechanisms. It was through the inspiration of a charismatic leader that people found something to believe in, and thereby change could be introduced into the system of continuous bureaucratic administration. The power of charismatic authority is accepted because followers are drawn to the leader’s personality. The appeal of a charismatic leader can be extraordinary, inspiring followers to make unusual sacrifices or to persevere in the midst of great hardship and persecution. Charismatic leaders usually emerge in times of crisis and offer innovative or radical solutions. They also tend to hold power for only short durations because power based on charisma is fickle and unstable.

The combination of the administrative power of rational-legal forms of domination and charisma have proven to be extremely dangerous, as the rise to power of Adolf Hitler shortly after Weber’s death demonstrated. Sociologists might also point to the distortions that the value of charisma introduces into the contemporary political process. There is increasing emphasis on the need to create a public “image” for leaders in electoral campaigns, both by “tweaking” and manufacturing the personal qualities of political candidates — Stephen Harper’s sudden propensity for knitted sweaters, Jean Chretien’s “little guy from Shawinigan” persona, Jack Layton’s moustache — and by character assassinations through the use of negative advertising — Stockwell Day as “scary, narrow-minded fundamentalist,” Paul Martin’s “Mr. Dithers” persona, Michael Ignatieff’s “the fly-in foreign academic” tag, Justin Trudeau’s “cute little puppy” moniker. Image management, or the attempt to manage the impact of one’s image or impression on others, is all about attempting to manipulate the qualities that Weber called charisma. However, while people often decry the lack of rational debate about the facts of policy decisions in image politics, it is often the case that it is only the political theatre of personality clashes and charisma that draws people in to participate in political life.

Media Attributions

- Figure 17.2 Canadian Parliament Buildings Ottawa by West Annex News, via Flickr, is used under CC BY SA 2.0 licence.

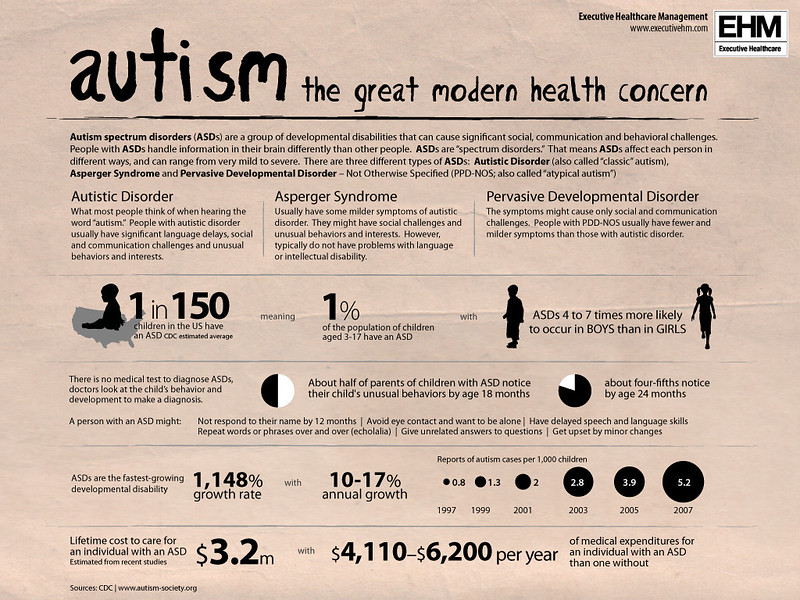

- Figure 17.3 Autism by GDS Infographics, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 17.4 Royal Wedding by Herry Lawford, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 17.5 Politik als Beruf cover of book by Max Weber (1919), via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 17.6 Tunisian Revolution -Jan20 DSC_5305 by Chris Belsten, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 17.7 Acropolis in Athens by Adam L. Clevenger, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under CC BY SA 2.5 licence.

- Figure 17.8 File:MAX WEBER.jpg by Power Renegadas, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence.

- Figure 17.9 Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes, engraving on cover page by Abraham Bosse, 1651, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

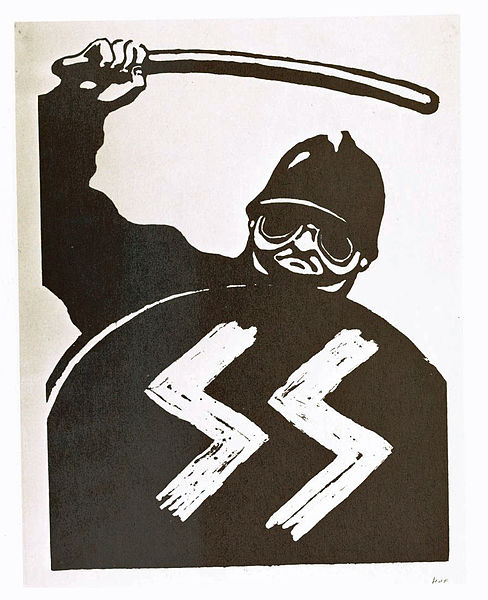

- Figure 17.10 Les Affiches de mai 68 ou l’Imagination graphique by Charles Perussaux, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 17.11 Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini in Munich, Germany, June 1940 (https://catalog.archives.gov/id/540151), from U.S. National Archives Catalog, National Archives Identifier: 540151, Local Identifier: 242-EB-7-38A, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 17.12 (left) Pierre Trudeau B&W by User:Connormah, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain; (right) Trudeau at the 2006 Liberal Party leadership convention is used under CC BY-SA 2.5 licence.