Chapter 5. Socialization

5.3. Agents of Socialization

Socialization helps people learn to function successfully in their social worlds. How does the process of socialization occur? How do people learn to use the objects of their society’s material culture? How do they come to adopt the beliefs, values, and norms that represent its nonmaterial culture? This learning takes place through interaction with various agents of socialization, like peer groups and families, plus both formal and informal social institutions.

Social Group Agents

Families, and later peer groups, often provide the first experiences of socialization. They communicate expectations and reinforce norms. People first learn to use the tangible objects of material culture in these settings, as well as being introduced to the beliefs and values of society.

Family

Family is the first agent of socialization. Mothers and fathers, siblings and grandparents, plus members of an extended family all teach a child what they need to know. For example, they show the child how to use objects (such as clothes, computers, eating utensils, books, bikes); how to relate to others (some as “family,” others as “friends,” still others as “strangers” or “teachers” or “neighbours”); and how the world works (what is “real” and what is “imagined”).

It is important to keep in mind, however, that families do not socialize children in a vacuum. Many social factors impact how a family raises its children. For example, students can use sociological imagination to recognize that individual behaviours are affected by the historical period in which they take place. Sixty years ago, it would not have been considered especially strict for a father to hit his son with a wooden stick or a belt if the child misbehaved, but today that same action might be considered child abuse.

Sociologists recognize that race, social class, religion, and other societal factors play an important role in socialization. For example, poor families usually emphasize obedience and conformity when raising their children, while wealthy families emphasize judgment and creativity (National Opinion Research Center, 2008). This may be because working-class parents have less education and more repetitive-task jobs for which the ability to follow rules and to conform helps. Wealthy parents tend to have better education and often work in managerial positions or in careers that require creative problem solving, so they teach their children behaviours that would be beneficial in these positions. This means that children are effectively socialized and raised to take the types of jobs that their parents already have, thus reproducing the class system (Kohn, 1977). Likewise, children are socialized to abide by gender norms, perceptions of race, and class-related behaviours.

In Sweden, for instance, stay-at-home fathers are an accepted part of the social landscape. A government policy provides subsidized time off work — 68 weeks for families with newborns at 80 per cent of regular earnings — with the option of 52 of those weeks of paid leave being shared between both mothers and fathers, and eight weeks each in addition allocated for the father and the mother. This encourages fathers to spend at least eight weeks at home with their newborns (Marshall, 2008). As one stay-at-home dad said, being home to take care of his baby son “is a real fatherly thing to do. I think that’s very masculine” (Associated Press, 2011). Overall, 90 per cent of Swedish men participate in the paid leave program.

In Canada on the other hand, outside of Quebec, parents can share 40 weeks of paid parental leave at 55% of their regular earnings (or 69 weeks at 33% of their regular earnings). Across Canada (including Quebec), between 2012 and 2017, 88% of mothers took maternity leave compared with 42% of fathers (Statistics Canada, 2021). In Quebec, where in addition to 32 weeks of shared parental leave, men also receive five weeks of paid leave, the participation rate of men is 93% (compared to 24% of fathers outside of Quebec). In Canada overall, the participation of men in paid parental leave increased from 34% from 2001–2006 to 42% in 2006. This does not include fathers who take sick leave, annual vacation leave, or benefits from an employer program to stay home with newborns, which is more common outside of Quebec. Researchers note that a father’s involvement in child raising has a positive effect on the parents’ relationship, the father’s personal growth, and the social, emotional, physical, and cognitive development of children (Marshall, 2008). How will this effect differ in Sweden and Canada as a result of the different nature of their paternal leave policies?

Peer Groups

A peer group is made up of people who are not necessarily friends but who are similar in age and social status and who share interests. Peer group socialization begins in the earliest years, such as when kids on a playground teach younger children the norms about taking turns, the rules of a game, or how to shoot a basket. Peer groups provide childrens’ first major socialization experience outside the realm of their families.

Randall Collins’ (2004) model of interaction rituals and emotional-entrainment describes the powerful socializing effect of early childhood interactions with peers. Interactions with other children while at play or in other situations gives the child a sense of the social order and their place within it outside the direct control of parents. An interaction ritual is defined as an interaction where individuals come together physically in a bounded situation, (i.e., in which it is clear who is participating and who is not), to participate in a mutual focus of attention that creates a shared emotional experience. At a micro-sociological level interaction rituals are mechanisms where socialization into group life occurs and gets reinforced.

Collins describes four outcomes of the socialization process in interaction rituals:

-

Group solidarity: a feeling of membership;

-

Emotional energy…in the individual: a feeling of confidence, elation, strength, enthusiasm, and initiative in taking action;

-

Symbols that represent the group: emblems or other representations (visual icons, words, gestures) that members feel are associated with themselves collectively…. Persons pumped up with feelings of group solidarity treat symbols with great respect and defend them against the disrespect of outsiders, and even more, of renegade insiders.

-

Feelings of morality: the sense of rightness in adhering to the group, respecting its symbols, and defending both against transgressors. Along with this goes the sense of moral evil or impropriety in violating the group’s solidarity and its symbolic representations (Collins, 2004).

Children’s play is an example of an interaction ritual. In play, children bring their attention to a common focus — an “emblem” such as a game, a toy, a ball, etc. — and become aware of, and mutually attuned to, each other’s attention to the object of interest. At a physical level they become rhythmically coordinated in a repetition of actions. At an emotional level they also become emotionally entrained or fixed on the common focus. They conform to each other’s emotions, which gradually build up and become increasingly intense through the self-reinforcing feedback mechanisms of play — the minor successes, failures, victories, betrayals, provisional agreements, etc. that make up the back and forth of events. Play is therefore an intense process of socialization and conformity into the norms and feelings of the group.

At the same time, playing with peers is a high-stakes game where children are socialized into relations of status, power and in/out groups; again, independently of their position within the family group. Through the flows of emotional energy in play some children become the center of attention and reap the emotional awards of confidence, respect, and prestige, which they can carry into other activities, whereas other children find themselves relegated to supporting roles or sidelined, where their access to the rewards and emotional energy of play is diminished. Some children cast as victims or excluded from play can be emotionally suppressed by play. Daycare centers and play groups can become enclosed “status goldfish bowls” where children divide themselves into cliques: “little groups of bullies and their scapegoats, popular play leaders and their followers, fearful or self-sufficient isolates” (Collins, 2004).

As children grow into teenagers, this process continues. Peer groups are important to adolescents in a new way, as they begin to develop an identity separate from their parents and exert independence. This is often a period of parental-child conflict and rebellion as parental values come into conflict with those of youth peer groups. Peer groups provide their own opportunities for socialization since kids usually engage in different types of activities with their peers than they do with their families. They are especially influential, therefore, with respect to preferences in music, style, clothing, etc., sharing common social activities, and learning to engage in romantic relationships. With peers, adolescents experiment with new experiences outside the control of parents: sexual relationships, drug and alcohol use, political stances, hair and clothing choices, and so forth. The most visible and highly structured cliques and in/out groups are probably found in high schools — nerds, jocks, preppies, stoners, rebels, religious evangelicals, etc..

Interestingly, studies have shown that although friendships rank high in adolescents’ priorities, this is balanced by parental influence. Conflict between parents and teenagers is usually temporary and in the end families exert more influence than peers over educational choices and political, social, and religious attitudes.

Peer groups might be the source of rebellious youth culture, but they can also be understood as agents of social integration. The seemingly spontaneous way that youth in and out of school divide themselves into cliques with varying degrees of status or popularity prepares them for the way the adult world is divided into status groups. The racial characteristics, gender characteristics, intelligence characteristics, and wealth characteristics that lead to being accepted in more or less popular cliques in school are the same characteristics that divide people into status groups in adulthood.

Institutional Agents

The social institutions of a culture also inform their processes of socialization. Formal institutions — like schools and workplaces — teach people how to behave in and navigate these systems. Other institutions, like the media, contribute to socialization by inundating people with messages about norms and expectations.

School

Most Canadian children spend about seven hours a day and 180 days a year in school, which makes it hard to deny the importance school has on their socialization. In elementary and junior high, compulsory education amounts to over 8,000 hours in the classroom (OECD, 2013). Students are not only in school to study math, reading, science, and other subjects — the manifest function of this system. Schools also serve a latent function in society by socializing children into behaviours like teamwork, following a schedule, and using textbooks.

School and classroom rituals, led by teachers serving as role models and leaders, regularly reinforce what society expects from children. Sociologists describe this aspect of schools as the hidden curriculum, the informal teaching done by schools.For example, in North America, schools have built a sense of competition into the way grades are awarded and the way teachers evaluate students. Students learn to evaluate themselves within a hierarchical system of A, B, C, etc. students (Bowles & Gintis, 1976). However, different lessons can be taught by different instructional techniques. When children participate in a relay race or a math contest, they learn that there are winners and losers in society. When children are required to work together on a project, they practice teamwork with other people in cooperative situations.Bowles and Gintis argue that the hidden curriculum prepares children for a life of conformity in the adult world. Children learn how to deal with bureaucracy, rules, expectations, to wait their turn, and to sit still for hours during the day. The latent functions of competition, teamwork, classroom discipline, time awareness, and dealing with bureaucracy are features of the hidden curriculum.Schools also socialize children by teaching them overtly about citizenship and nationalism. In the United States, children are taught to say the Pledge of Allegiance. Most school districts require classes about U.S. history and geography. In Canada, on the other hand, critics complain that students do not learn enough about national history, which undermines the development of a sense of shared national identity (Granatstein, 1998). But this might also be a way of socializing students into the Canadian national identity, which prides itself in a weak attachment to political institutions and nationalistic projects, allowing citizens to be detached from patriotic sentimentality.Textbooks in Canada are also continually scrutinized and revised to update attitudes toward the different cultures in Canada as well as perspectives on historical events; thus, children are socialized to a different national or world history than earlier textbooks may have done. For example, recent textbook editions include information about the colonial mistreatment of First Nations which more accurately reflects those events than in textbooks of the past. In this regard, schools educate students explicitly about aspects of citizenship important for being able to participate in a modern, heterogeneous culture.

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

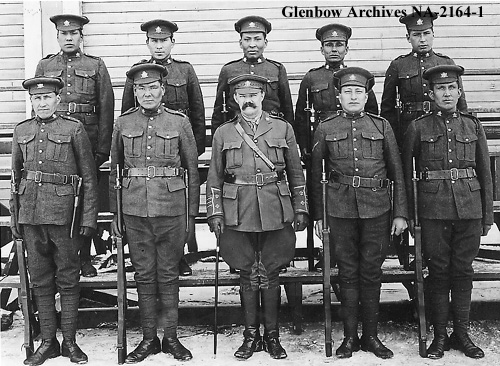

Mike Mountain Horse: Socialization on First Day at Residential School

In 1893, six-year-old Mike Mountain Horse, a member of the Blood (Kainai) First Nation in what is now southern Alberta, was enrolled in the Anglican boarding school on the Blood Reserve. His brother Fred was already attending the school and was there to provide guidance on his first day.

My Indian clothes, consisting of blanket, breech cloth, leggings, shirt and moccasins, were removed. Then my brother took me into another room where I was placed in a steaming brown fibre paper tub full of water. Yelling blue murder, I started to jump out, but my brother held on to me and I was well scrubbed and placed before a heater to dry. Next came Mr. Swainson [the principal] with a pair of shears. I was again placed in a chair. Zip went one of my long braids to the floor: the same with the other side. A trim was given as a finish to my haircut. My brother again took me in charge. “Don’t cry any more,” he said. “You are going to get nice clothes.” Mrs. Swainson then came into the room with a bundle of clothes for me: knee pants, blouse to match with a wide lace collar, a wee cap with an emblem sewn in front, and shoes. Thus attired I strutted about like a young peacock before the other pupils.

The education at the school was conducted in English, but, Mountain Horse recalled, the church services were held in Siksika (Blackfoot). To encourage students to learn English, the principal offered to honour any request for a gift that was written in English. To test the system, Mountain Horse requested, and received, a pound of butter and a can of milk. It was, he discovered, more butter than he had use for, and he threw it out.

Although one of the key goals of the school was to convert the students to the Christian faith, Mountain Horse wrote that “the powerful sway of the new was not sufficient to entirely dethrone the many spirits to whom we had previously made our offerings.” In the end, however, he said, “The majority of the Indian youth have no alternative than to embrace the religion of the white man as taught in their schools.”

Mountain Horse went on to attend the Calgary industrial school. After graduating, he went to work for the Mounted Police, served in the First World War, returned to work for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, wrote the manuscript of his book on the Bloods, and ended his career as a railway labourer.

Mike Mountain Horse account, in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. (2015). Canada’s Residential Schools: The History, Part 1, Origins to 1939. Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (Volume 1, pp. 174–175). McGill-Queen’s University Press. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission Final Report is in the public domain.

The Workplace

Just as children spend much of their day at school, most Canadian adults at some point invest a significant amount of time at a place of employment. After school, the workplace is the next major institution of socialization that people encounter in their lives. Although socialized into their culture since birth, workers require new socialization into a workplace both in terms of material culture (such as how to operate the copy machine) and nonmaterial culture (such as whether it is okay to speak directly to the boss or how the refrigerator is shared).

Different jobs require different types of socialization. In the past, many people worked a single job until retirement. Today, the trend is to switch jobs at least once a decade. Between the ages of 18 and 44, the average baby boomer of the younger set held 11 different jobs (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010). This means that people must become socialized to, and socialized by, a variety of work environments.

One common feature of workplace socialization is learning time discipline and efficiency. At work, people are required to make continuous productive use of time and avoid idleness, and they are disciplined or fired if they do not. E.P. Thompson (1967) described the historical shift from a pre-industrial ‘task orientation’ in work to an industrial ‘time orientation’ in work. In pre-industrial societies the workday was organized according to the tasks that needed to be accomplished, with little attention paid to clock-time, whereas in industrial societies the workday is organized according to regulated, coordinated clock-time and the need to intensify productivity per unit of standardized time. This shift altered time sense from natural, irregular, cyclical and experientially comprehensible time, blurring work and leisure, to an artificial and abstract time sense based on the invention and implementation of mechanical clocks that sharply divided work and leisure and imposing an external synchronization of labour through timed work and concepts of efficiency. As Thompson points out, this imposition of clock-time on the labour process was not universally accepted by workers. It took place against resistance over a period of centuries, but gradually spread beyond the workplace to dominate society as a whole. The socialization effect of the modern workplace has to do with the internalization of clock-time along with a sense of urgency in getting tasks done within a specific, albeit artificial, time frame.

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

Girls and Movies

Pixar is one of the largest producers of children’s movies in the world and has released large box office draws, such as Toy Story, Cars, The Incredibles, and Up. What Pixar has never before produced is a movie with a female lead role. This changed with Pixar’s movie Brave in 2012. Before Brave, women in Pixar served as supporting characters and love interests. In Up, for example, the only human female character dies within the first ten minutes of the film. For the millions of girls watching Pixar films, there are few strong characters or roles for them to relate to. If they do not see possible versions of themselves, they may come to view women as secondary to the lives of men.

The animated films of Pixar’s parent company, Disney, have many female lead roles. Disney is well known for films with female leads, such as Snow White, Cinderella, The Little Mermaid, and Mulan. Many of Disney’s movies star a female, and she is nearly always a princess figure. If she is not a princess to begin with, she typically ends the movie by marrying a prince or, in the case of Mulan, a military general. Although not all “princesses” in Disney movies play a passive role relative to male characters, they typically find themselves needing to be rescued by a man, and the happy ending they all search for includes marriage.

Alongside this prevalence of princesses, many parents express concern about the culture of princesses that Disney has created. Peggy Orenstein addresses this problem in her popular book, Cinderella Ate My Daughter. Orenstein wonders why every little girl is expected to be a “princess” and why pink has become an all-consuming obsession for many young girls. Another mother wondered what she did wrong when her three-year-old daughter refused to do “non-princessy” things, including running and jumping. The effects of this princess culture can have negative consequences for girls throughout life. An early emphasis on beauty and sexiness can lead to eating disorders, low self-esteem, and risky sexual behaviour among older girls.

What should we expect from Pixar’s Brave, the company’s first film to star a female character? Although Brave features a female lead, she is still a princess. Will this film offer any new type of role model for young girls? (Barnes, 2010; O’Connor, 2011; Rose, 2011).

Mass Media

Mass media refers to the distribution of impersonal information to a wide audience via television, newspapers, radio, and the internet. With the average person spending over four hours a day in front of the TV (and children averaging even more screen time), media greatly influences social norms (Roberts, Foehr, & Rideout, 2005; Oliveira, 2013). Statistics Canada reports that for the sample of people they surveyed about their time use in 2010, 73 per cent said they watched 2 hours 52 minutes of television on a given day (see the Participants column in Table 5.1 below).

Television continues to be the mass medium that occupies the most free time of the average Canadian, but the internet has become the fastest growing mass medium. In the Statistics Canada survey, television use on a given day declined from 77 per cent to 73 per cent between 1998 and 2010, but computer use increased amongst all age groups from 5 per cent to 24 per cent and averaged 1 hour 23 minutes on any given day. People who played video games doubled from 3 per cent to 6 per cent between 1998 and 2010, and the average daily use increased from 1 hour 48 minutes to 2 hours 20 minutes (Statistics Canada, 2013).

Through media, people learn about objects of material culture (like new technology, transportation, and consumer options), as well as nonmaterial culture—what is true (beliefs), what is important (values), and what is expected (norms). This can be beneficial as a way that people are socialized about the norms, expectations, and values of their society, but also harmful when media messages distort reality or present unrealistic images and expectations. For example, sex, as many films, television shows, music videos, and song lyrics present it, is frequent and casual. Rarely do these media point out the potential emotional and physical consequences of sexual behavior. Additionally, actors and models depicted in sexual relationships in the media are thinner, younger, and more attractive than the average adult. This creates unrealistic expectations about the necessary ingredients for a satisfying sexual relationship. Media representations can therefore socialize people into expectations of norms and standards that are unhinged from the lived experiences of everyday life.

| Activity group | Population | Participants | Participation rate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | |

| hours and minutes | hours and minutes | percentage | |||||||

| 1. Television, reading, and other passive leisure | 02:29 | 02:39 | 02:20 | 03:08 | 03:19 | 02:58 | 79 | 80 | 79 |

| Watching television | 02:06 | 02:17 | 01:55 | 02:52 | 03:03 | 02:41 | 73 | 75 | 71 |

| Reading books, magazines, newspapers | 00:20 | 00:18 | 00:23 | 01:26 | 01:29 | 01:25 | 24 | 20 | 27 |

| Other passive leisure | 00:03 | 00:03 | 00:02 | 01:04 | 01:16 | 00:52 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 2. Active leisure | 01:13 | 01:27 | 00:59 | 02:22 | 02:42 | 02:01 | 51 | 54 | 49 |

| Active sports | 00:30 | 00:37 | 00:23 | 01:54 | 02:12 | 01:34 | 26 | 28 | 25 |

| Computer use | 00:20 | 00:23 | 00:17 | 01:23 | 01:32 | 01:14 | 24 | 25 | 23 |

| Video games | 00:09 | 00:14 | 00:04 | 02:20 | 02:40 | 01:38 | 6 | 9 | 4 |

| Other active leisure | 00:14 | 00:13 | 00:15 | 02:05 | 02:06 | 02:04 | 11 | 10 | 12 |

| Note. Average time spent is the average over a 7-day week. Source: Statistics Canada, General Social Survey, 2010 (Statistics Canada, 2011). Note: this survey asked approximately 15,400 Canadians aged 15 and over to report in a daily journal details of the time they spent on various activities on a given day. Because they were reporting about a given day, the figures sited about the average use of television and other media differ from reports provided by BBM and other groups on the average weekly usage, like the figure of 4 hours per day of TV cited in Roberts, Foehr, and Rideout (2005) above. |

|||||||||

Media Attributions

- Figure 5.16 I’ll bathe you, Baby! by Nurse Terri/ Nate Griggs, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 5.17 Chic Chick Clique – Modenschau in Projekt B-22 by Udo Herzog is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 5.18 Thunder Hill Elementary School Kindergarten Tour by Howard County Library System, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence.

- Figure 5.19 Blood recruits, 191st Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force, Fort Macleod, Alberta from the Glenbow Museum, Image No: NA-2164-1, is in the public domain.

- Figure 5.20 Some more presents… by Emily Stanchfield, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.