Chapter 14. Marriage and Family

Learning Objectives

14.1 What Is Marriage? What Is a Family?

- Define the family and the difficulties sociologists have in formulating a substantive definition.

- Analyze historical and cross-cultural variations in marriage and family patterns.

- Outline the sociological approach to the dynamics of attraction and romantic love.

- Understand the effect of the family life cycle on the quality of the family experience.

- Describe micro, meso, macro and global approaches to the family.

14.2 Variations in Family Life

- Recognize variations in family life.

- Describe the different forms of the family, including the nuclear family, single-parent families, cohabitation, same-sex couples, and unmarried individuals.

- Discuss the functionalist, critical, and symbolic interactionist perspectives on the modern family.

- Understand the social and interpersonal impact of divorce.

- Describe the problems of family abuse, and discuss whether corporal punishment is a form of abuse.

Introduction to Marriage and Family

Christina and James met in university and have been dating for more than five years. For the past two years, they have been living together in a condo they purchased jointly. While Christina and James were confident in their decision to enter into a commitment (such as a 20-year mortgage), they are unsure if they want to enter into marriage. The couple had many discussions about marriage and decided that it just did not seem necessary. Was it not just a piece of paper? Did not half of all marriages end in divorce?

Neither Christina nor James had seen much success with marriage while growing up. Christina was raised by a single mother. Her parents never married, and her father has had little contact with the family since she was a toddler. Christina and her mother lived with her maternal grandmother, who often served as a surrogate parent. James grew up in a two-parent household until age seven, when his parents divorced. He lived with his mother for a few years, and then later with his mother and her boyfriend until he left for college. James remained close with his father who remarried and had a baby with his new wife.

Recently, Christina and James have been thinking about having children and the subject of marriage has resurfaced. Christina likes the idea of her children growing up in a traditional family, while James is concerned about possible marital problems down the road and negative consequences for the children should that occur. When they shared these concerns with their parents, James’s mom was adamant that the couple should get married. Despite having been divorced and having a live-in boyfriend of 15 years, she believes that children are better off when their parents are married. Christina’s mom believes that the couple should do whatever they want but adds that it would “be nice” if they wed. Christina and James’s friends told them, married or not married, they would still be a family.

Christina and James’ dilemma is shared by many couples today. Zygmunt Bauman (2003) has argued that in late modernity, institutions, including marriage, have become increasingly fluid: uncertain, insecure, impermanent. In one’s life one might expect to go through a number of career changes, a number of identities, as well as a number of intimate partners. Love and intimacy are anchors in an unpredictable and unfixed world, but they can also be fleeting and untrustworthy. To commit to another in marriage involves a gamble that the other, (and oneself), will remain committed to the relationship through time. Among other things, long term commitment closes the door on other romantic possibilities, which could prove more satisfying and fulfilling.

As Bauman puts it,

Interpersonal relationships with all their accompaniments – love, partnerships, commitments, mutually recognized rights and duties – are simultaneously objects of attraction and apprehension, desire and fear; sites of two-mindedness and hesitation, soul-searching, anxiety (Bauman, 2004).

Does this mean that the family is in crisis or decline?

Christina and James’s scenario may be complicated, but it is representative of the lives of many young couples today, particularly those in urban areas. Statistics Canada (2019a) reports that the number of unmarried, common-law couples grew by 3 times between 1981 and 2016, to make up a total of 21.3% of all couples in Canada. This is much higher than in the United States where only 5.9% of couples cohabited outside of marriage in 2010, but about the same as the UK (20% in 2015) and lower than Sweden (29% in 2010). In Quebec, 39.9% of couples lived common law, whereas in Nunavut the figure was 50.3%.

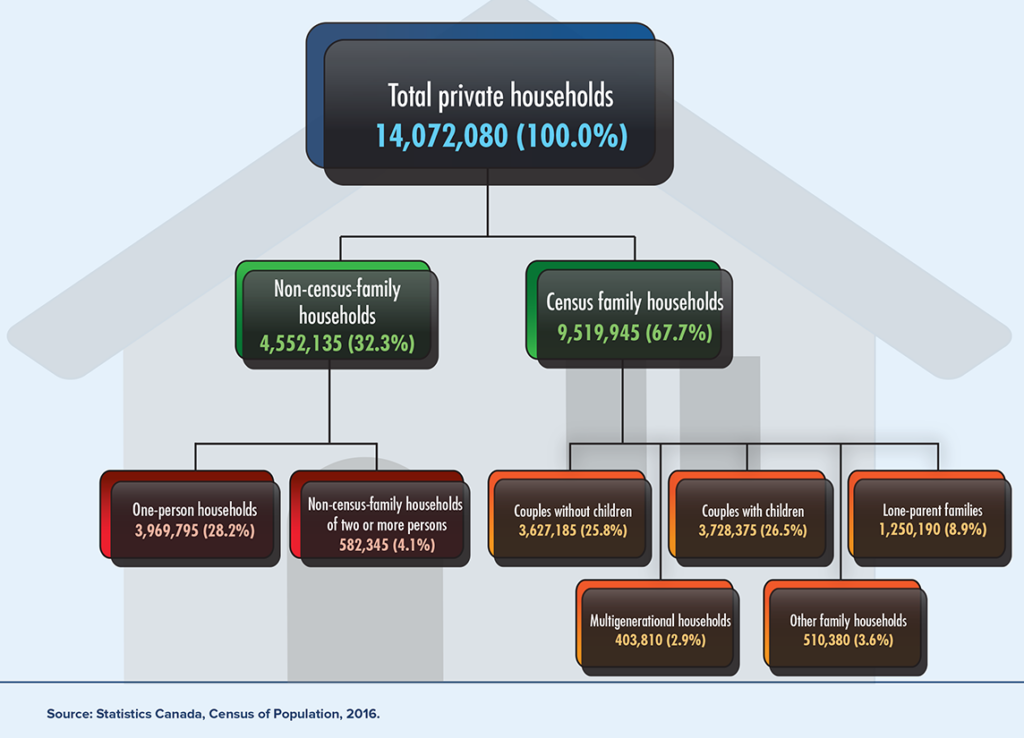

While more married couples than ever reported having lived common-law before getting married in 2016 (39%), some common-law couples may never choose to wed (Statistics Canada, 2019b). The most common type of household in 2016 was in fact one-person households or singles (28.2%). With fewer couples marrying, the traditional Canadian family structure is becoming less common. Nevertheless, although the percentage of traditional married couples has declined as a proportion of all families, 56% of all people aged 25–64 were officially married in 2016, (compared to 15% living common law, 13% never married or lived common law, 6 per cent divorced, 8 per cent separated from common-law partner, and 1 per cent widowed). For people aged 25-64, marriage is still by far the predominant living arrangement in Canada.

Image Descriptions

Figure 14.2 long description: Overview of Household Types, Canada, 2016.

Total private households: 14,1072,080 (100.0%)

- Non-census-family households: 4552,135 (32.3%)

- One-person households: 3,969,795 (28.2%)

- Non-census-family households of two or more persons: 582,345 (4.1%)

- Census family households: 9,519,945 (67.7%)

- Couples without children: 2,627,185 (25.8%)

- Couples with children: 3,728,375 (26.5%)

- Lone-parent families: 1,250,190 (8.9%)

- Multigenerational households: 403,810 (2.9%)

- Other family households: 510,380 (3.6%) [Return to Figure 14.2]

Media Attributions

- Figure 14.1 French Canadian Habitants playing at cards, print sold by R. & C. Chalmers, via Library and Archives Canada, Item title: c000057k, ID: 2836668, is in the public domain.

- Figure 14.2 Overview of household types, Canada, 2016 by Statistics Canada (2019b) is used under the Statistics Canada Open Licence.