Chapter 8. Deviance, Crime, and Social Control

8.4. Public Policy Debates on Crime

The sociological study of crime, deviance, and social control is especially important with respect to public policy debates. In 2012 the Conservative government passed the Safe Streets and Communities Act, a controversial piece of legislation because it introduced mandatory minimum sentences for certain drug or sex related offenses, restricted the use of conditional sentencing (i.e., non-prison punishments), imposed harsher sentences on certain categories of young offender, reduced the ability for Canadians with a criminal record to receive a pardon, and made it more difficult for Canadians imprisoned abroad to transfer back to a Canadian prison to be near family and support networks. The legislation imposed a mandatory six-month sentence for cultivating six marijuana plants, for example.

Noting that the mandatory minimum sentencing disproportionately affected Indigenous and Black Canadians, the Liberal government passed Bill C-22 in 2021, which repealed mandatory minimum sentencing for 14 offenses in the criminal code, including all 6 provisions that applied to the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (Department of Justice Canada, 2021). Approximately 39 per cent of Black inmates and 20 per cent of Indigenous prisoners in federal prisons were serving sentences dictated by mandatory minimums. Supreme court rulings had already struck down two mandatory minimums for firearm offenses in 2015, declaring them “cruel,” and drug-related minimums in 2016, on the grounds that they violated the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. However, the Bill C-22 reform leaves 52 offenses with mandatory minimums in place.

Government policy shifts back and forth between a punitive approach to crime control and preventive strategies such as drug rehabilitation, prison diversion, and social reintegration programs. Why? Part of the reason has to do with the discourses surrounding crime. Despite the evidence that rates of serious and violent crime have been falling in Canada, in 2011 Justice Minister Rob Nicholson said, “Unlike the Opposition, we do not use statistics as an excuse not to get tough on criminals. As far as our Government is concerned, one victim of crime is still one too many” (Galloway, 2011). What accounts for the appeal of “getting tough on criminals” policies at a time when rates of crime, and violent crime in particular, are falling and in 2012 were at their lowest level since 1972 (Perreault, 2013)? Crime rates have since risen but remain lower than they were in 2009 (Moreau, Jaffray and Armstrong, 2020).

One reason is that violent crime is a form of deviance that lends itself to spectacular media coverage that distorts its actual threat to the public. Television news broadcasts frequently begin with chaos news — crime, accidents, natural disasters — that present an image of society as a dangerous and unpredictable place. However, the image of crime presented in the headlines does not accurately represent the types of crime that actually occur. Whereas the news typically reports on the worst sorts of violent crime, violent crime made up only 22 per cent of all police-reported crime in 2019 (down 3 per cent from 2009), and homicides made up only one-tenth of 1 per cent of all violent crimes in 2019 (Moreau, Jaffray and Armstrong, 2020). An analysis of television news reporting on murders in 2000 showed that while 44 per cent of CBC news coverage and 48 per cent of CTV news coverage focused on murders committed by strangers, only 12 per cent of murders in Canada are committed by strangers. Similarly, while 24 per cent of the CBC reports and 22 per cent of the CTV reports referred to murders in which a gun had been used, only 3.3 per cent of all violent crime involved the use of a gun in 1999. In 1999, 71 per cent of violent crimes in Canada did not involve any weapon (Miljan, 2001).

The issue is that the news is a commercial product used to sell newspapers and advertising. “If it bleeds, it leads” is the adage that describes the financial motivation to publish the most dramatic crime news because it sells more subscriptions and receives more views. Czerny and Swift (1988) argue that the commercial media distort the content of the news in a number of ways. Typically stories emphasize:

- the intense (stories are selected to play up drama and action)

- the unambiguous (complex issues and lived experiences are simplified into straightforward moral stories of good and bad)

- the familiar (stories are made to fit in with common sense understandings and prejudices)

- the marketable (stories are packaged to appeal to consumer tastes, often with sex and violence imagery)

This distortion is amplified by the use of on-line sources where about 60% of Canadians report getting their news most of the time (Canadian Journalism Foundation, 2019). In particular, emotional responses to stories rather than critical analysis influence people’s decisions to “retweet” a story (Stieglitz & Dang–Xuan, 2013). Emotions have also been shown to be contagious in on-line environments and are linked to rumor spreading behaviour (Kramer et al., 2014; Oh et al. 2013; Pröllochs et al., 2021). alsehood diffused significantly farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than the truth in all categories of information.”

Media distortion can create the conditions for moral panics around crime. A moral panic occurs when a relatively minor or atypical situation of deviance arises that is exaggerated and distorted by the media, police, or members of the public. It thereby comes to be defined as a general threat to the civility or moral fibre of society (Cohen, 1972). As public attention is brought to the rule breakers, more instances are discovered, dire predictions are made, and the rule breakers are rebranded as “folk devils” who endanger and disrupt society. Authorities then react by taking social control measures disproportionate to the original acts of deviance. Relatively isolated occurences of deviance get caught up in an amplification cycle. As Cohen sums up, “It is the perception of threat and not its actual existence that is important” (Cohen, 1972).

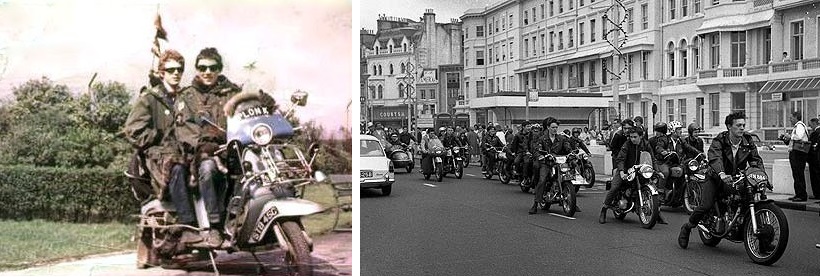

Stanley Cohen’s (1972) original example of the phenomenon was the Mods and Rockers confrontations in Margate, Brighton, Clacton and Bournemouth — oceanside resort towns in England — in the 1960s. The Mods and Rockers became well known as distinctive British youth subcultures, but only after some minor incidents of scuffling and stone throwing in the streets of Clacton on Easter, 1964, were blown up in the national newspapers: “Day of Terror by Scooter Groups” (Daily Telegraph), ‘Youngsters Beat Up Town – 97 Leather Jacket Arrests’ (Daily Express), “Wild Ones Invade Seaside – 97 Arrests” (Daily Mirror) (Cohen, 1972). The publicity set the scene for further confrontations between the groups in seaside towns throughout the summer, the heavy deployment of combined police forces, the extension of police powers, calls for banning Mod/Rocker clothing and long hair, and demands for the Home Secretary to hold an inquiry and take firm action.

Like subsequent examples of moral panic in Canada over gang violence, unemployed male youth, paedophilia, “nasty girls,” high school shootings, satanism, and date rape drugs, etc. (O’Grady, 2014), the Mods and Rockers became visible social types that stood as symbols of social degeneration and of moral boundaries that should not be crossed. In particular, they amplified the public’s ambivalent feelings about Britain in the 1960s becoming an ‘affluent society’ and focused them onto young people who were seen to be rejecting adult ideals: “the response was as much to what they stood for as what they did” (Cohen 1972). Panics happen in part because they fulfill a function of reaffirming society’s moral values.

In addition to the media, one way in which certain activities or people come to be understood and defined as deviant is through the intervention of moral entrepreneurs. Howard Becker defined moral entrepreneurs as individuals or groups who, in the service of their own interests, publicize and problematize “wrongdoing” and have the power to create and enforce rules to penalize wrongdoing (1963). Judge Emily Murphy, commonly known today as one of the Famous Five feminist suffragists who fought to have women legally recognized as “persons” (and thereby qualified to hold a position in the Canadian Senate), was also a moral entrepreneur instrumental in changing Canada’s drug laws. In 1922 she wrote The Black Candle, in which she raised alarms about the use of cannabis (as well as Chinese opium dens, white slavery, Black train porters selling drugs and pornography, etc.):

[Cannabis] has the effect of driving the [user] completely insane. The addict loses all sense of moral responsibility. Addicts to this drug, while under its influence, are immune to pain, and could be severely injured without having any realization of their condition. While in this condition they become raving maniacs and are liable to kill or indulge in any form of violence to other persons, using the most savage methods of cruelty without, as said before, any sense of moral responsibility…. They are dispossessed of their natural and normal will power, and their mentality is that of idiots. If this drug is indulged in to any great extent, it ends in the untimely death of its addict (Murphy, 1922).

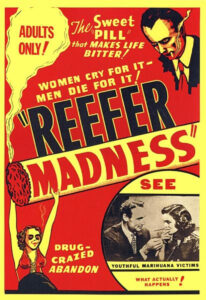

In his analysis of the Marijuana Tax Act in the United States, Becker (1963) shows how moral entrepreneurs like Emily Murphy play an instrumental role in generating public concern about a particular condition, mounting a “symbolic crusade” aided by publicity and the actions of supporting interest groups, and producing a moral enterprise: “the creation of a new fragment of the moral constitution of society.”

Creating moral panic is one tactic used by moral entrepreneurs to make activities, like marijuana use, seem deviant and in need of social control. The framework for the moral crisis might change through time however. For example, in 2012 the implementation of mandatory minimum sentences for the cultivation of marijuana was framed in the Safe Streets and Communities legislation as a response to the infiltration of organized crime into Canada. For years newspapers uncritically published police messaging on grow-ops and the marijuana trade that characterized the activities as widespread, gang-related, and linked to the cross-border trade in guns and more serious drugs like heroin and cocaine. Television news coverage often showed police in white, disposable hazardous-waste outfits removing marijuana plants from suburban houses, and presented exaggerated estimates of the street value of the drugs. However a Justice Department study in 2011 revealed that out of a random sample of 500 grow-ops, only 5 per cent had connections to organized crime. Moreover, an RCMP-funded study from 2005 noted that “firearms or other hazards” were found in only 6 per cent of grow-op cases examined (Boyd & Carter, 2014). While 76 per cent of Canadians at the time believed that cannabis should be legally available (Stockwell et al., 2006), and several jurisdictions (Washington and Colorado states, and Uruguay) had already legalized cannabis, the Safe Streets and Communities Act appeared to be an attempt to reinvigorate the punitive messaging of the “war on drugs” based on disinformation and moral panic around marijuana use and cultivation.

Conclusions

One of the principle outcomes of these sociological insights is that a focus on the social construction of different social experiences and problems leads to alternative ways of understanding them and responding to them. In the study of crime and deviance, the sociologist often confronts a legacy of entrenched beliefs concerning either the innate biological disposition or the individual psychopathology of persons considered abnormal: the criminal personality, the sexual or gender “deviant,” the “bad seed,” the addict, or the mentally unstable individual. However, as Ian Hacking observed, even when these beliefs about “kinds of persons” are products of objective scientific classification, the institutional context of science and expert knowledge is not independent of societal norms, beliefs, and practices (2006).

The process of classifying kinds of people is a social process that Hacking called “making up people” (2006) and Howard Becker called “labeling” (1963). Crime and deviance are social constructs that vary according to the definitions of crime, the forms and effectiveness of policing, the social characteristics of criminals, and the relations of power that structure society. Part of the problem of deviance is that the social process of labeling some kinds of persons or activities as abnormal or deviant limits the type of social responses available. The major issue is not that labels are arbitrary, nor that it is possible not to use labels at all, but that the choice of label has consequences. Who gets labelled by whom and the way social labels are applied have powerful social repercussions. Therefore, it is necessary to use the sociological imagination to address crime and deviance both at the individual and social levels. With a deeper understanding of the social factors that produce crime and deviance, it becomes possible to develop a set of strategies that might more effectively encourage individuals to change direction when their acts are harmful to others, to society and to themselves.

The sociological study of crime, deviance, and social control is especially important with respect to public policy debates. The political controversies that surround the question of how best to respond to crime are difficult to resolve at the level of political rhetoric. Often, in the news and public discourse, the issue is framed in moral terms; therefore, for example, the policy alternatives get narrowed to the option of either being “tough” on crime or “soft” on crime. Tough and soft are moral categories that reflect a moral characterization of the issue. A question framed by these types of moral categories cannot be resolved by using evidence-based procedures.

Posing the debate in these terms narrows the range of options available and undermines the ability to raise questions about which responses to crime actually work. In fact policy debates over crime seem especially susceptible to the various forms of specious reasoning described in Chapter 2. Sociological Research (“Science vs. Non-Science”). The story of the isolated individual whose specific crime becomes the basis for the belief that the criminal justice system as a whole has failed illustrates several qualities of unscientific thinking: knowledge based on casual observation, knowledge based on overgeneralization, and knowledge based on selective evidence. Moral categories of judgement pose the problem in terms that are unfalsifiable and non-scientific.

The sociological approach is essentially different. It focuses on the effectiveness of different social control strategies for addressing different types of criminal behaviour and the different types of risk to public safety. Thus, from a sociological point of view, it is crucial to think systematically about who commits crimes and why. It is also crucial to look at the big picture to see why certain acts are considered normal and others deviant, or why certain acts are criminal and others are not. In a society characterized by large inequalities of power and wealth, as well as large inequalities in arrest and incarceration, an important social justice question needs to be examined regarding who gets to define whom as criminal or deviant.

This chapter has illustrated the sociological imagination at work by examining the “individual troubles” of criminal behaviour and victimization within the social structures that sustain them. In this regard, sociology is able to advocate policy options that are neither hard nor soft, but evidence-based and systematic.

Media Attributions

- Figure 8.22 Cover scan of a Famous Crimes by Unknown at Fox Features Syndicate, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 8.23a Mods a bordo di Lambretta 175 TV 3ª serie del 1962, ampiamente modificata by Sergio Calleja, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 licence.

- Figure 8.23b Mods and Rockers, Hastings by Phil Sellens is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 8.24 Reefer Madness by Motion Picture Ventures, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.