Chapter 17. Government and Politics

17.2 Democratic Will Formation

Most people presume that anarchy, or the absence of organized government, does not facilitate a desirable living environment for society. They have in the back of their minds the Hobbesian view that the absence of sovereign rule leads to a state of chaos, lawlessness, and war of all against all. However, anarchy literally means “without leader or ruler.” Anarchism therefore refers to the political principles and practice of organizing social life without formal or state leadership. As such, the radical standpoint of anarchism provides a useful standpoint from which to examine the sociological question of why leadership in the form of the state is needed in the first place. This question will be addressed again in the final section of this chapter.

The tradition of anarchism developed in Europe in the 19th century in the work of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809–1865), Mikhail Bakunin (1814–1876), Peter Kropotkin (1842–1921) and others. It promoted the idea that states were both artificial and malevolent constructs, unnecessary for human social organization (Esenwein 2004). Anarchists proposed that the natural state of society is one of self-governing collectivity, in which people freely group themselves in loose affiliations with one another rather than submitting to government-based or state-made laws. They had in mind the way rural farmers came together to organize farmers’ markets or the cooperative associations of Swiss watchmakers in the Jura mountains. For the anarchists, anarchy was not violent chaos but the cooperative, egalitarian society that would emerge when state power was destroyed.

The anarchist program was (and still is) to maximize the personal freedoms of individuals by organizing society on the basis of voluntary social arrangements. These arrangements would be subject to continual renegotiation. As opposed to right-wing libertarianism, which focuses only on minimizing state intervention, the anarchist tradition argued that the conditions for a cooperative, egalitarian society were the destruction of both the power of the state and of private property (i.e., capital). Libertarian critique tends to leave the market, the power of corporations and other institutional hierarchies, like religion, intact, whereas one of Proudhon’s famous anarchist slogans was “Private property is theft!” (Proudhon 1840).

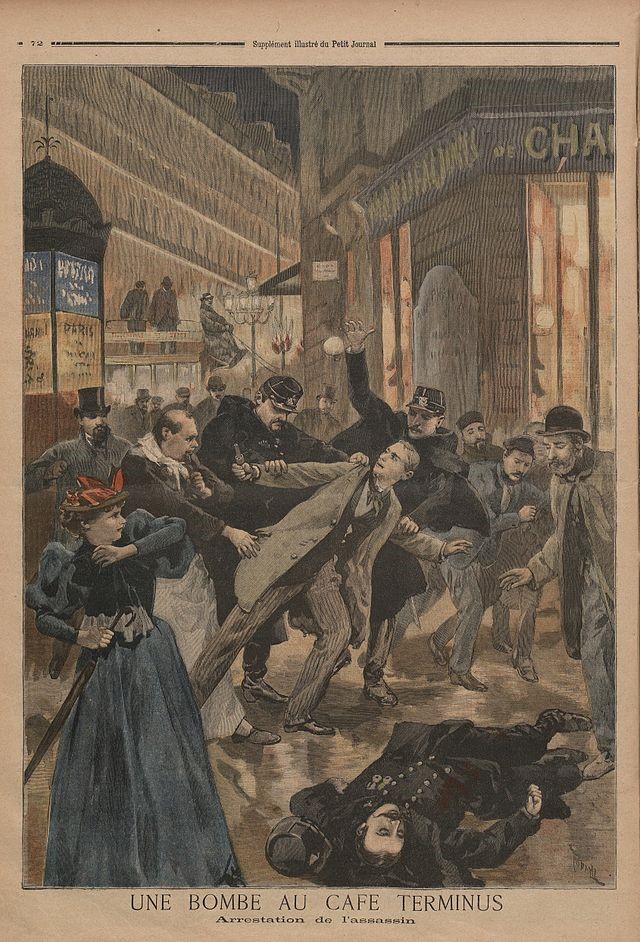

In practice, 19th century anarchism had the dubious distinction of inventing modern political terrorism, or the use of violence on civilian populations and institutions to achieve political ends (Coulter, 2011). This was referred to by Mikhail Bakunin as “propaganda by the deed” (1870). Clearly not all or even most anarchists advocated violence in this manner, but it was widely recognized that the hierarchical structures and institutions of the old society had to be destroyed before the new society could be created.

Nevertheless, the principle of the anarchist model of government is based on the participatory or direct democracy of the ancient Greek Athenians. In Athenian direct democracy, decision making, even in matters of detailed policy, was conducted through assemblies made up of all citizens. These assemblies would meet a minimum of forty times a year (Forrest 1966). The root of the word democracy is demos, Greek for “people.” Democracy is therefore rule by the people. Ordinary Athenians directly ran the affairs of Athens. Of course, “all citizens,” for the Greeks, meant all adult men and excluded women, children, and slaves.

Direct democracy can be contrasted with modern forms of representative democracy, like that practiced in Canada. In representative democracy, citizens elect representatives (MPs, MLAs, city councillors, etc.) to promote policies that stand for their interests rather than directly participating in decision making themselves. It is based on the idea of representation rather than direct citizen participation.

Critics note that the representative model of democracy enables distortions to be introduced into the determination of the will of the people: elected representatives are typically not socially representative of their constituencies, as they are dominated by white men and elite occupations like law and business; corporate media ownership and privately funded advertisement campaigns enable the interests of privileged classes to be expressed in politics rather than those of average citizens; and lobbying and private campaign contributions provide access to representatives and decision-making processes that is not afforded to the majority of the population. The distortions that intrude into the processes of representative democracy — for example, whose interests really get represented in government policy? — are no doubt behind the famous comment of the former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill who once declared to the House of Commons, “Indeed it has been said that democracy is the worst form of government … except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time” (Shapiro 2006).

Democracy however is not a static political form. Three key elements constitute democracy as a dynamic system: the institutions of democracy (parliament, elections, constitutions, rule of law, etc.), citizenship (the internalized sense of individual dignity, rights, and freedom that accompanies formal membership in the political community), and the public sphere (or open “space” for public debate and deliberation). On the basis of these three elements, rule by the people can be exercised through a process of democratic will formation.

Jürgen Habermas (1998) emphasizes that democratic will formation in both direct and representative democracy is reached through a deliberative process. The general will or decisions of the people emerge through the mutual interaction of citizens in the public sphere. The underlying norm of the democratic process is what Habermas (1990) calls the ideal speech situation. An ideal speech situation is one in which every individual is permitted to take part in public discussion equally: to question assertions and introduce ideas. Ideally no individual is prevented from speaking (not by arbitrary restrictions on who is permitted to speak, nor by practical restrictions on participation like poverty or lack of education). To the degree that everyone accepts this norm of openness and inclusion, free debate provides a forum where the best ideas will “rise to the top” and be accepted by the majority. On the other hand, when the norms of the ideal speech situation are violated, the process of democratic will formation becomes distorted and open to manipulation.

Political Demand and Political Supply

In practice democratic will formation in representative democracies takes place largely through political party competition in an electoral cycle. Two factors explain the dynamics of democratic party systems: political demand and political supply (Kitschelt, 1995).

Firstly, political demand refers to the underlying societal factors and social changes that create constituencies of people with common interests. People form common political preferences and interests on the basis of their position within the social structure. For example, changes in the types of jobs generated by the economy will affect the size of electoral support for labour unions and labour union politics.

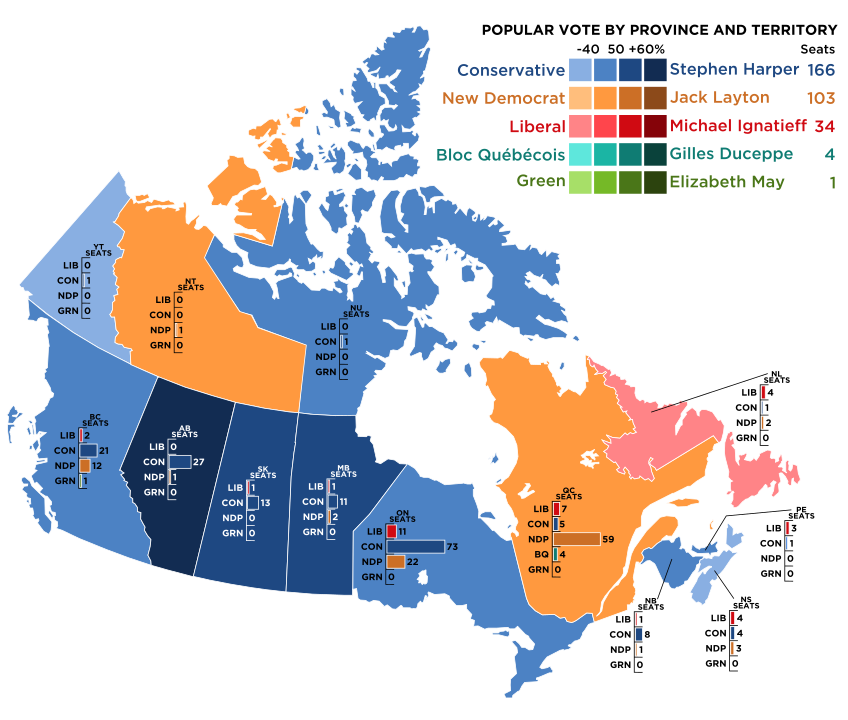

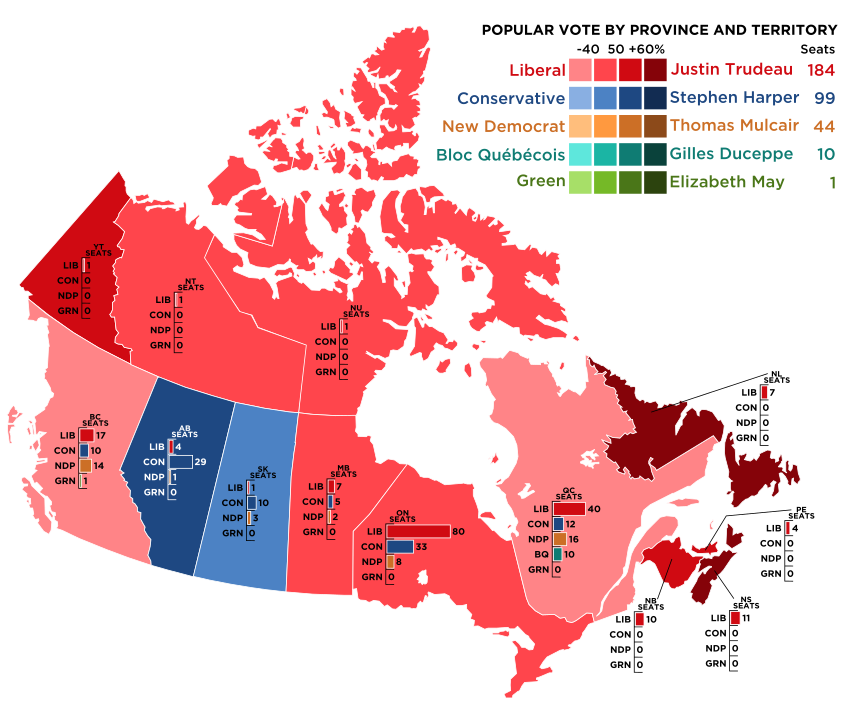

Secondly, political supply refers to the strategies and organizational capacities of political parties to deliver an appealing political program to particular constituencies. For example, the Liberal Party of Canada often attempts to develop policies and political messaging that will position it in the middle of the political spectrum where the largest group of voters potentially resides. In the 2011 election, due to leadership issues, organizational difficulties, and the strategies of the other political parties, they were not able to deliver a credible appeal to their traditional centrist constituency and suffered a large loss of seats in Parliament (see Figure 17.15). In the 2015 election, the Conservative Party’s program and messaging consolidated its “right wing” constituency of social conservatives and free market proponents but failed to appeal to a sufficient number of people in the center of the Canadian political spectrum to maintain control of government (see Figure 17.15).

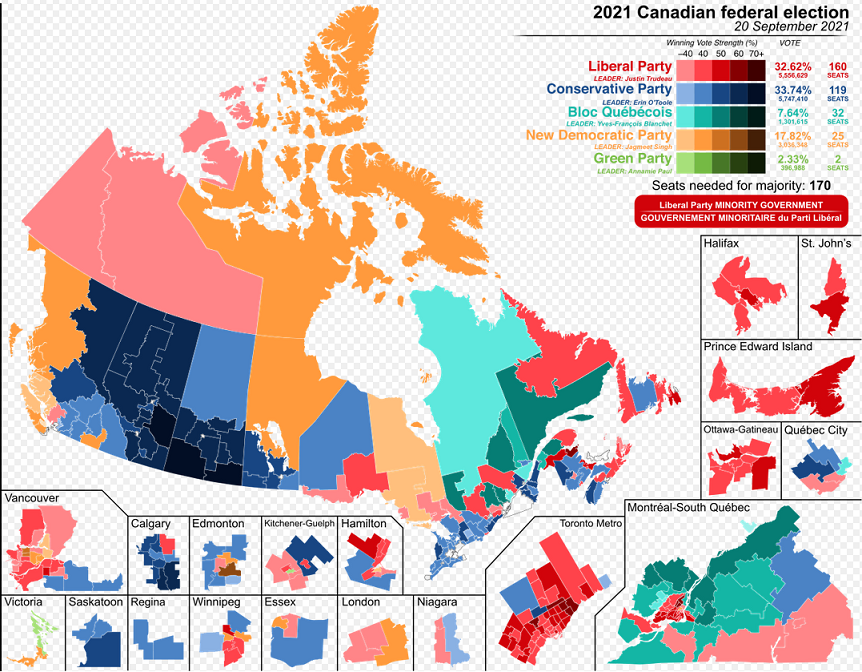

In the 2019 and 2021 federal elections minority parliaments were elected, meaning that none of the parties won sufficient seats to hold a majority. In part this appears to be a product of the first-past-the-post electoral system, regionalism, and the fragmentation of political supply in the centre and centre-left parties, where approximately 60% of the population divided its vote between Liberals, Bloc Quebecois, NDP, and Greens. In both the 2019 and 2021 elections, the Conservatives had difficulty in providing leadership, a platform, and clear messaging, and failed to balance their appeal to both the centrist constituency and the right wing. One product of this was the emergence of a small white nationalist, libertarian constituency to the right of the Conservatives between the 2019 and 2021 elections, which consolidated around the People’s Party but without securing any seats.

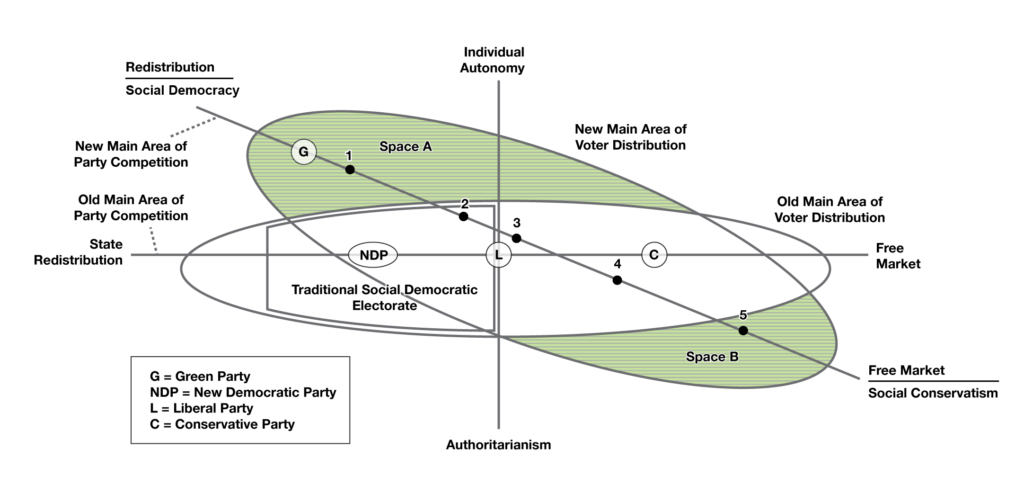

The relationship between political demand and political supply factors in democratic will formation can be illustrated by mapping out constituencies of voters on a left/right spectrum of political preferences (Kitschelt, 1995; see Figure 17.17). While the terms “left wing” and “right wing” are notoriously ambiguous (Ogmundson, 1972), they are often used in a simple manner to describe the basic political divisions of modern society.

In Figure 17.17, one central axis of division in voter preference has to do with the question of how scarce resources are to be distributed in society. At the right end of the spectrum are economic conservatives who advocate minimal taxes and a purely spontaneous, competitive market-driven mechanism for the distribution of wealth and essential services (including health care and education), while at the left end of the spectrum are socialists who advocate progressive taxes and state redistribution of wealth and services to create social equality or “equality of condition.”

A second axis of division in voter preference has to do with social policy and collective decision modes. At the right end of the spectrum is authoritarianism (law and order, limits on personal autonomy, exclusive citizenship, hierarchical decision making, etc.), while at the left end of the spectrum is individual autonomy or expanded democratization of political processes (maximum individual autonomy in politics and the cultural sphere, equal rights, inclusive citizenship, extra-parliamentary democratic participation, etc.).

Along both axes or spectra of political opinion, one might imagine an elliptically shaped distribution of individuals, with the greatest portion in the middle of each spectrum and far fewer people at the extreme ends. The dynamics of political supply in political party competition follow from the way political parties try to position themselves along the spectrum to maximize the number of voters they appeal to while remaining distinct from their political competitors.

Sociologists are typically more interested in the underlying social factors contributing to changes in political demand than in the day-by-day strategies of political supply. One influential theory proposes that since the 1960s, contemporary political preferences have shifted away from older, materialist concerns with economic growth and physical security (i.e., survival values) to postmaterialist concerns with quality-of-life issues: personal autonomy, self-expression, environmental integrity, women’s rights, gay rights, the meaningfulness of work, habitability of cities, etc. (Inglehart 2008). From the 1970s on, postmaterialist social movements seeking to expand the domain of personal autonomy and free expression have encountered equally postmaterialist responses by neoconservative groups advocating the return to traditional family values, religious fundamentalism, submission to work discipline, and tough-on-crime initiatives. This has led to a new postmaterialist cleavage structure in political preferences.

Figure 17.17 represents this shift in political preferences in the difference between the ellipse centred on the free-market/state redistribution axis and the ellipse centred on the free-market-social-conservativism/ redistribution-social-liberalism axis (Kitschelt, 1995). As a result of the development of postmaterialist politics, the “left” side of the political spectrum has been increasingly defined by a cluster of political preferences defined by redistributive policies, social and multicultural inclusion, environmental sustainability, and demands for personal autonomy, etc., while the “right” side has been defined by a cluster of preferences including free-market policies, tax cuts, limits on political engagement, “tough” on crime policy, and social conservative values, etc.

What explains the emergence of a postmaterialist axis of political preferences? Again, sociologists focus on how the effects of globalization, changes in economic structure, factors such as immigration, and emergent issues like climate change and Aboriginal reconciliation affect political demand. Arguably, the experience of citizens for most of the 20th century was defined by economic scarcity and depression, the two World Wars, and the Cold War resulting in the materialist orientation toward the economy, personal security, crime issues and military defence in political demand. The location of individuals within the industrial class structure is conventionally seen as the major determinant of whether they preferred working-class-oriented policies of economic redistribution or capitalist-class-oriented policies of free-market allocation of resources.

In the advanced capitalist or postindustrial societies of the 21st century, the underlying class conditions of voter preference are not so clear. Certainly, the working class does not vote en masse for the traditional working-class party in Canada, the NDP, and voters from the big business, small business, and administrative classes are often divided between the Liberals and Conservatives (Ogmundson, 1972). Some have argued that the shift from Keynesian, welfare state economic policies of the post-War period to neoliberal policies of the 1980s–2000s has itself begun to shift to an uncertain post-neoliberal politics of authoritarian populism on one side (Davies and Gane, 2021) and a “Green New Deal” (Osberg, 2021) on the other.

Kitschelt (1995) notes two distinctly influential dynamics in Western European social conditions that can be applied to the political demand dynamics of the Canadian situation. Firstly, in the era of globalization and free trade agreements people (both workers and managers) who work in and identify with sectors of the economy that are exposed to international competition (non-quota agriculture, manufacturing, natural resources, finances) are likely to favour free market policies that are seen to enhance the global competitiveness of these sectors, while those who work in sectors of the economy sheltered from international competition (public-service sector, education, and some industrial, agricultural and commercial sectors) are likely to favour redistributive policies. Secondly, in the transition from an industrial economy to a postindustrial service and knowledge economy, people whose work or educational level promotes high levels of communicative interaction skills (education, social work, health care, cultural production, etc.) are likely to value personal autonomy, free expression, quality of life and increased democratization, whereas those with more instrumental task-oriented occupations (manipulating objects, documents, and spreadsheets) and lower or more skills-oriented levels of education are likely to find authoritarian and traditional social settings more natural. In Figure 17.17, new areas of political preference are shown opening up in the shaded areas labelled Space A and Space B.

The implication Kitschelt draws from this analysis is that as the conditions of political demand shift, the strategies of the political parties (i.e., political supply) need to shift as well (see Figure 17.17). Social democratic parties like the NDP need to be mindful of the general shift to the right under conditions of globalization and global competition (especially as the industrial work force in Canada diminishes), but to the degree that they move to the centre (2) or the right (3), like British Labour under Tony Blair (from 1997 to 2007), they risk alienating much of their traditional core support in the union movement, new social movement activists, and young people. The Green Party is also positioned (1) to pick up NDP support if the NDP move right. On the other side of the spectrum, the Conservatives do not want to move so far to the right (5) that they lose centrist voters to the Liberals or NDP (as was the case in the federal elections in 2015, 2019 and 2021). However, to the degree they move to the centre they risk being indistinguishable from the Liberals and a space opens up to the right of them on the political spectrum, which can be exploited by a party like the People’s Party. The demise of the former Progressive Conservative party after the 1993 election was precipitated by the emergence of postmaterialist conservative parties further to the right (Reform and the Canadian Alliance).

This model of democratic will formation in Canada is not without its problems. For one thing, Kitschelt’s model of the spectrum of political party competition is based on European politics. It does not take into account the importance of regional allegiances that cut across the left/right division and make Canada an atypical case (in particular the regional politics of Quebec and Western Canada). Similarly, the argument that political preferences have shifted from materialist concerns with economic growth and distribution to postmaterialist concerns with quality-of-life issues is belied by opinion polls which consistently indicate that Canadians rate the economy, employment and housing affordability as their greatest concerns, (although climate change and health care often rank highly as well). On the other hand, it is probably the case that postmaterialist concerns are not addressed effectively in current formal political processes and political party platforms. Canadians have been turning increasingly to nontraditional political activities like protests and demonstrations, signing petitions, and boycotting to express their political grievances and aspirations.

With regard to the distinction between direct democracy and representative democracy, it is interesting to note that in the current era of fluctuating voter participation in elections, people (especially young people) are turning to more direct means of political engagement (See Table 17.2). Where typically these extra-parliamentary protest movements have mobilized younger people around “left-wing” concerns like social justice, racial inclusion, patriarchy and environmental issues, increasingly “right-wing” groups have mobilized older people in direct actions to promote white nationalism or anti-taxation, anti-carbon pricing and anti-vaccine mandates, framed as libertarian individualist issues.

| Types of Political Participation | Total | 15 to 21 | 22 to 29 | 30 to 44 | 45 to 64 | 65 or older |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow news and current affairs daily | 68*% | 35*% | 51% | 66*% | 81*% | 89*% |

| Voted in at least one election | 77*% | N/A | 59% | 71*% | 85*% | 89*% |

| Voted in the last federal election | 74*% | N/A | 52% | 68*% | 83*% | 89*% |

| Voted in the last provincial election | 73*% | N/A | 50% | 66*% | 82*% | 88*% |

| Voted in the last municipal or local election | 60*% | N/A | 35% | 52*% | 70*% | 79*% |

| At least one non-voting political behaviour | 54*% | 59% | 58% | 57% | 56% | 39*% |

| Searched for information on a political issue | 26*% | 36% | 32% | 26*% | 25*% | 17*% |

| Signed a petition | 28*% | 27*% | 31% | 31% | 29% | 16*% |

| Boycotted a product or chose a product for ethical reasons | 20*% | 16*% | 25% | 25% | 21*% | 8*% |

| Attended a public meeting | 22*% | 17% | 16% | 23*% | 25*% | 20*% |

| Expressed their views on an issue by contacting a newspaper or a politician | 13*% | 8% | 9% | 13*% | 16*% | 12*% |

| Participated in a demonstration or march | 6*% | 12*% | 8% | 6% | 6*% | 2*% |

| Spoke out at a public meeting | 8*% | 4% | 5% | 9*% | 10*% | 7*% |

| Volunteered for a political party | 3% | 2% | 3% | 2% | 4*% | 4% |

Note. Voting rates will differ from those of Elections Canada, which calculates voter participation rates based on number of eligible voters. N/A = not applicable. *Statistically different from 22- to 29-year-olds (p<0.05). Source: General Social Survey (Statistics Canada, 2003).

Media Attributions

- Figure 17.13 Pierre-Jospeh Proudhon, by unknown photographer, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 17.14 Attentat de l’hôtel Terminus by Osvaldo Tofani (1849–1915), via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 17.15 Canada 2011 Federal Election by Noname224. via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY SA 2.5 licence.

- Figure 17.16 Canada 2015 Federal Election by Noname2 , via Wikimedia Commons, is used under CC BY SA 2.5 licence. (Created from maps by by Gage and Lokal_Profil)

- Figure 17.17 Map of results for the 2021 Canadian federal election on 20 September 2021 by Eric0892, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under CC BY-SA 4.0 licence. (Map data from Statistics Canada, Natural Earth, and OpenStreetMap.)

- Figure 17.18 The space of political competition in public will formation, adapted from Kitschelt 1995 for this textbook by H. Anggraeni, Thompson Rivers University Open Learning.