Chapter 12. Gender, Sex, and Sexuality

12.1 The Difference between Sex, Gender, and Sexuality

When filling out a document such as a job application or school registration form people are often asked to provide their name, address, phone number, birth date, and sex or gender. But what if they were asked to provide their sex and their gender? It does not occur to many people that sex and gender are not the same. Sociologists view sex and gender as conceptually distinct for a number of reasons. Sex refers to physical or physiological differences between males and females, including both primary sex characteristics (the reproductive system) and secondary characteristics such as height and muscularity. Gender is a term that refers to social or cultural distinctions and roles associated with being male or female. Gender identity is the extent to which one identifies as being either masculine or feminine (Diamond, 2002). As gender is such a primary dimension of identity, socialization, institutional structures and life chances, sociologists refer to it as a core status.

The distinction between sex and gender is key to being able to examine gender as a social variable rather than biological variable. Contrary to the common way of thinking about it, gender is not determined by biology in any simple way. For example, the anthropologist Margaret Mead’s cross-cultural research in New Guinea in the 1930s was groundbreaking in its demonstration that cultures differ markedly in the ways that they perceive the gender “temperaments” of men and women; i.e., their masculinity and femininity (Mead, 1963). Unlike the qualities that defined masculinity and femininity in North America at the time, she saw both genders among the Arapesh as sensitive, gentle, cooperative, and passive, whereas among the Mundugumor both genders were assertive, violent, jealous, and aggressive. Among the Tchambuli, she described male and female temperaments as the opposite of those observed in North America. The women appeared assertive, domineering, emotionally inexpressive and managerial, while the men appeared emotionally dependent, fragile, and less responsible.

The experience of transgender people — people whose sense of gender does not correspond to their assigned sex at birth — also demonstrates that a person’s sex, as determined by their biology, does not always correspond with their gender. Therefore, the terms sex and gender are not interchangeable. A baby boy who is born with male genitalia will be identified as male. As he grows, however, he may identify with the feminine aspects of his culture. Since the term sex refers to biological or physical distinctions, characteristics of sex will not vary significantly between different human societies. For example, it is physiologically normal for persons of the female sex, regardless of culture, to eventually menstruate and develop breasts that can lactate. The signs and characteristics of gender, on the other hand, may vary greatly between different societies as Margaret Mead’s research noted. For example, in American culture, it is considered feminine (or a trait of the female gender) to wear a dress or skirt. However, in many Middle Eastern, Asian, and African cultures, dresses or skirts (often referred to as sarongs, robes, or gowns) can be considered masculine. The kilt worn by a Scottish male does not make him appear feminine in his culture. These examples are relatively trivial, but the variability can also be consequential, such as the appropriateness or even legality of women holding a paying job, driving a car, or even being seen in public (Schiappa, 2022).

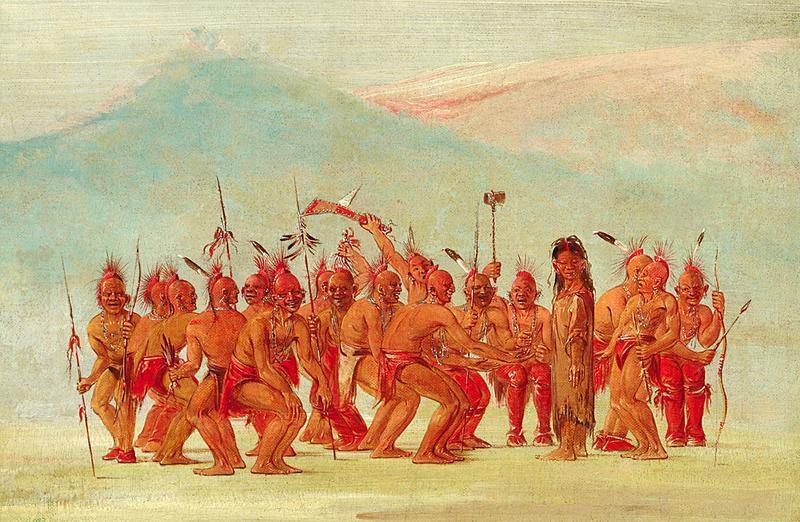

The dichotomous view of gender (the notion that one is either male or female) is specific to certain cultures and is not universal. In some cultures, gender is viewed as fluid. In the past, some anthropologists used the term berdache or two spirit person to refer to individuals who occasionally or permanently dressed and lived as the opposite gender. The practice has been noted among certain Aboriginal groups (Jacobs, Thomas, and Lang, 1997). Samoan culture accepts what they refer to as a “third gender.” Fa’afafine, which translates as “in the manner of a woman,” is a term used to describe individuals who are born biologically male but have a strong inclination to feminine activities and identity, and take part in traditional women’s work. Fa’afafines are considered an important part of Samoan culture. Individuals from other cultures may mislabel them as homosexuals but fa’afafines have a varied sexual life that may include attraction to men or women (Poasa, 1992).

In North American culture, gender variability refers to the larger social category of people who identify as gender nonconformist, genderqueer, nonbinary, or other terms that challenge the traditional binary language of gender (Schiappa, 2022).

Making Connections: Social Policy and Debate

The Legalese of Sex and Gender

The terms sex and gender have not always been differentiated in the English language. It was not until the 1950s that American and British psychologists and other professionals working with intersex and transgender patients formally began distinguishing between sex and gender. Since then, psychological and physiological professionals have increasingly used the term gender (Moi, 2005). By the end of the 20th century, expanding the proper usage of the term gender to everyday language became more challenging — particularly where legal language is concerned. In an effort to clarify usage of the terms sex and gender, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia wrote in a 1994 briefing, “The word gender has acquired the new and useful connotation of cultural or attitudinal characteristics (as opposed to physical characteristics) distinctive to the sexes. That is to say, gender is to sex as feminine is to female and masculine is to male” (J.E.B. v. Alabama, 144 S. Ct. 1436 [1994]). Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg had a different take, however. Viewing the words as synonymous, she freely swapped them in her briefings so as to avoid having the word “sex” pop up too often. It is thought that her secretary supported this practice by suggestions to Ginsberg that “those nine men” (the other Supreme Court justices), “hear that word and their first association is not the way you want them to be thinking” (Case, 1995).

In Canada, there has not been the same formal deliberations on the legal meanings of sex and gender. The distinction between sex as a physiological attribute and gender as social attribute has been used without controversy. However, things can get a little tricky when biological “sex” is regarded as simply a natural fact, especially in the case of transgender individuals who have undergone sex reassignment surgery and hormone replacement therapy (Cowan, 2005). For example, in British Columbia, people who have surgery to change their anatomical sex can apply through the provisions of the Vital Statistics Act to have their birth certificate changed to reflect their post-operative sex. But if a person was born male, does this mean that after sex reassignment surgery that person is fully regarded as a female in the eyes of the law?

In the 2002 case of Nixon v. Vancouver Rape Relief Society, a male-to-female transsexual, Kimberly Nixon brought an application to the B.C. Human Rights Tribunal that she had been discriminated against by the Vancouver Rape Relief Society (VRR) when her application to volunteer as a helper was rejected. The controversy was not over whether Kimberly was a woman, but whether she was woman enough for the position. VRR argued that as Kimberly had not grown up as a woman, she did not have the requisite lived experience as a woman in patriarchal society to counsel women rape victims. The B.C. Human Rights Tribunal ruled against VRR, finding that they had discriminated against Kimberly as a transgender woman. The ruling was overturned by the Supreme Court of British Columbia, which argued that the Act ‘‘did not address all the potential legal consequences of sex reassignment surgery’’ (Cowan, 2005). The court acknowledged that the meaning of both sex and gender vary in different contexts.

Ultimately the BC Supreme Court found that Vancouver Rape Relief ‘s failure to recognize Kimberly Nixon as a woman constituted discrimination but, because of the organization’s unique status, was not obligated to engage or train her as a volunteer. The BC Human Rights Code has a provision that protects organizations that work in areas of discrimination against identifiable groups. Section 41 states that such an “organization or group must not be considered to be contravening this code because it is granting preference to members of an identifiable group or class of persons.” Vancouver Rape Relief had the right to freedom of assembly and to organize itself as a women-only space, regardless of gender identity. It also had the right to define this space based on its own definition of a woman as someone who has lived their entire life as a female.

These legal issues reveal that even an intimate human experience that is assumed to be deeply personal (such as self-perception, self-identification and behaviour) is subject to social definitions and legal regulations. As Chambers (2007) summarizes it, “Nixon can say she is a woman, and, in most contexts, the law will support her self-definition. Yet other women, and women’s groups, are under no legal obligation to accept her as the woman she claims to be.” The question of “what makes a woman” in the case of Nixon v. Vancouver Rape Relief Society was a matter of the procedures of formal legal decision-making as much as it was a matter of biology, gender or lived experience.

Sexuality

Sexuality refers to a person’s capacity for sexual feelings and their emotional and sexual attraction to a particular sex (male or female). In social life sexuality has four components that sociologists typically study: (1) Sexual orientation (attraction to a particular sex); (2) Sexual identities (such as straight, queer, butch, femme or genderqueer); (3) Sexual practices (the type of sexual activity engaged in or fantasized); (4) Sexual social forms (such as monogamy, polyamory, pornography, sexual rites of passage, purity balls, laws of adultery, age of consent).

Sexuality or sexual orientation is typically divided into four categories: heterosexuality, the attraction to individuals of the opposite sex; homosexuality, the attraction to individuals of one’s own sex; bisexuality, the attraction to individuals of either sex; and asexuality, no attraction to either sex. Heterosexuals and homosexuals may also be referred to informally as “straight” and “gay,” respectively. North America is a heteronormative society, meaning it supports heterosexuality as the norm. This is referred to as heteronormativity. Consider that homosexuals are often asked, “When did you know you were gay?” but heterosexuals are rarely asked, “When did you know that you were straight?” (Ryle, 2011).

According to current scientific understanding, individuals are usually aware of their sexual orientation between middle childhood and early adolescence (American Psychological Association, 2008). They do not have to participate in sexual activity to be aware of these emotional, romantic, and physical attractions; people can be celibate and still recognize their sexual orientation. Homosexual women (also referred to as lesbians), homosexual men (also referred to as gays), and bisexuals of both genders may have very different experiences of discovering and accepting their sexual orientation. At the point of puberty, some may be able to claim their sexual orientations while others may be unready or unwilling to make their homosexuality or bisexuality known since it goes against North American society’s historical norms (APA, 2008).

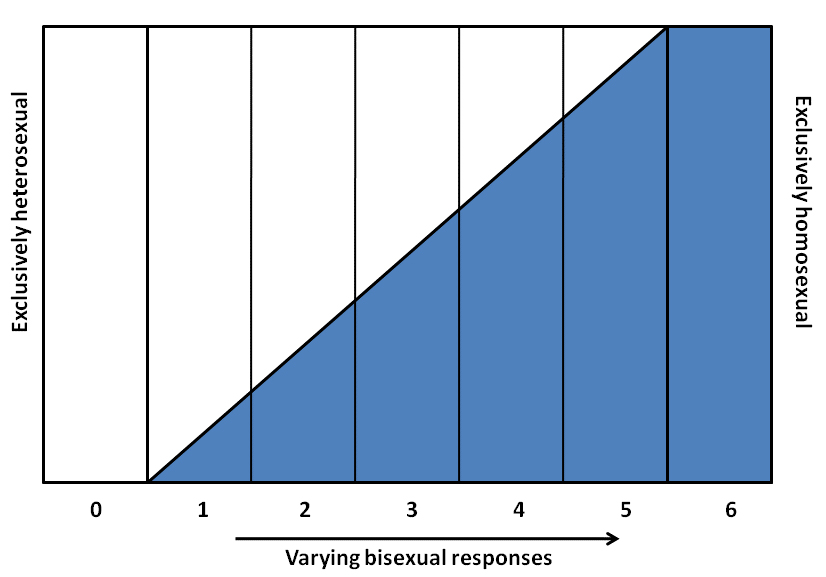

Alfred Kinsey was among the first to conceptualize sexuality as a continuum rather than a strict dichotomy of gay or straight. To classify this continuum of heterosexuality and homosexuality, Kinsey created a six-point rating scale that ranges from exclusively heterosexual to exclusively homosexual (see Figure 12.4). In his 1948 work Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, Kinsey writes, “Males do not represent two discrete populations, heterosexual and homosexual. The world is not to be divided into sheep and goats … The living world is a continuum in each and every one of its aspects” (Kinsey et al., 1948).

Later scholarship by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick expanded on Kinsey’s notions. She coined the term “homosocial” to oppose “homosexual,” to include nonsexual same-sex relations. Sedgwick recognized that in heteronormative North American culture, males are subject to a clear divide between the two sides of this continuum, whereas females enjoy more fluidity. This can be illustrated by the way women in Canada can express homosocial feelings (nonsexual regard for people of the same sex) through hugging, hand-holding, and physical closeness. In contrast, Canadian males often refrain from these expressions since they violate the heteronormative code. While women experience a flexible norming of variations of behaviour that spans the heterosocial-homosocial spectrum, male behaviour is subject to strong social sanction if it veers into homosocial territory because of societal homophobia (Sedgwick, 1985).

There is no scientific consensus regarding the exact reasons why an individual holds a heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual orientation. There has been research conducted to study the possible genetic, hormonal, developmental, social, and cultural influences on sexual orientation, but there has been no evidence that links sexual orientation to one factor (APA, 2008). Research, however, does present evidence showing that homosexuals and bisexuals are treated differently than heterosexuals in schools, the workplace, and the military. The 2009 Canadian Climate Survey reported that 59% of LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender) high school students had been subject to verbal harassment at school compared to 7% of non-LGBT students; 25% had been subject to physical harassment compared to 8% of non-LGBT students; 31% had been subject to cyber-bullying (via internet or text messaging) compared to 8% of non-LGBT students; 73% felt unsafe at school compared to 20% of non-LGBT students; and 51% felt unaccepted at school compared to 19% of non-LGBT students (Taylor and Peter, 2011).

Much of this discrimination is based on stereotypes, misinformation, and homophobia — an extreme or irrational aversion to homosexuals. Major policies to prevent discrimination based on sexual orientation have not come into effect until the last few years. In 2005, the federal government legalized same-sex marriage. The Civil Marriage Act now describes marriage in Canada in gender neutral terms: “Marriage, for civil purposes, is the lawful union of two persons to the exclusion of all others” (Civil Marriage Act, S.C. 2005, c. 33). The Canadian Human Rights Act was amended in 1996 to explicitly prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation, including the unequal treatment of gay men, lesbians, and bisexuals. Organizations such as Egale Canada (Equality for Gays And Lesbians Everywhere) advocate for LGBT and LGBTQ2+ rights, establish gay pride organizations in Canadian communities, and promote gay-straight alliance support groups in schools. Sociologists frequently use the acronym LGBTQ2+, which stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or “questioning,” two spirited, plus related non-binary or minority sexual identity communities.

Gender Roles: Masculinities and Femininities

As people grow up, they learn how to behave from those around them. In this socialization process, children are introduced to certain roles that are typically linked to their biological sex. The term gender role refers to a society’s concept of how men and women are expected to act, what types of things they should do and how they should behave. These social roles are based on norms, or standards, created by a society including the typical personality traits that define masculinity and femininity.

In Canadian culture, masculine roles are often associated with strength, aggression, and dominance, while feminine roles are often associated with passivity, nurturing, and subordination. As a result, men tend to outnumber women in professions such as law enforcement, the military, and politics. Women tend to outnumber men in care-related occupations such as child care, health care, and social work. These occupational roles are examples of typical Canadian male and female gender roles, derived from the culture’s traditions. Adherence to these occupational gender roles demonstrates fulfillment of social expectations, but not necessarily personal preference (Diamond, 2002).

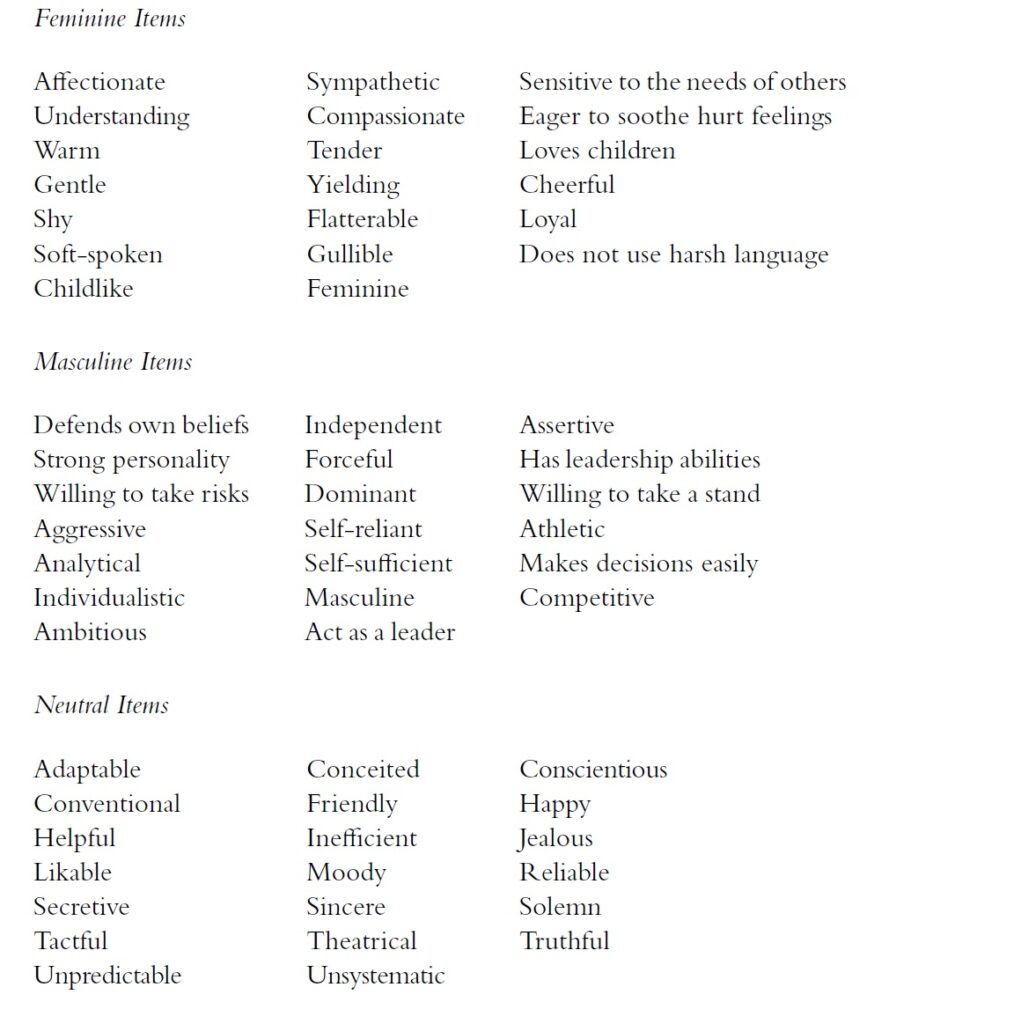

In 1974, Bem introduced the Bem Sex-Role Inventory based on what were considered masculine and feminine personality traits in North America. It allowed her to classify individuals on a spectrum of masculine, feminine, or ‘androgynous’ characteristics independently of their biological assignation. A given person might score high on the masculinity scale, or on the femininity scale, or both. The internalization of these traits, Bem suggested, was a matter of socialization. As she described it, the “sex-typed person” is “someone who has internalized society’s sex-typed standards of desirable behavior for men and women” (Bem, 1974). For sociologists, these items are especially interesting because they provide a list of socially approved gender characteristics for men and women, at least as they were perceived in 1974.

Bem’s research indicates that there is considerable variation in the performance of and adherence to gender roles. Connell (1995) elaborated on this by pointing to the existence of multiple styles of masculinity and femininity that are in operation in a culture at any particular time. These styles are not fixed and can change over time, both in the individual and in the culture. There is more than one kind of masculinity and femininity and what is considered “masculine” or “feminine” differs by race, class, ethnicity, sexuality, and gender.

For example, styles of masculinity and femininity are often associated with stereotypes that carry some truth. Stereotypical styles of masculinity in North American culture can include the jock, the nerd, the ladies’ man, the grunt, the maverick, the effeminate man, etc., whereas stereotypical styles of femininity can include the Madonna, the promiscuous woman, the independent woman, the tomboy, the femme, the badass girl, the new age goddess, etc. The key point in Connell’s analysis, however, is that the different styles of gender are not perceived equally. They exist in a hierarchical order defined by specific dominant or “hegemonic” understandings of masculinity and femininity.

Hegemonic masculinity is the dominant male ideal within a particular culture at a particular time (Connell, 1995). David and Brannon (1976) describe four rules for establishing masculinity:

-

No Sissy Stuff: anything that even remotely hints of femininity is prohibited. A real man must avoid any behavior or characteristic associated with women;

-

Be a Big Wheel: masculinity is measured by success, power, and the admiration of others. One must possess wealth, fame, and status to be considered manly;

-

Be a Sturdy Oak: manliness requires rationality, toughness, and self‐ reliance. A man must remain calm in any situation, show no emotion, and admit no weakness;

-

Give ’em Hell: men must exude an aura of daring and aggression, and must be willing to take risks, to “go for it” even when reason and fear suggest otherwise.

Hegemonic masculinity operates as a gender norm, and it is against this norm that the many different types of lived masculinities, including gay, racialized and ethnic masculinities, are invited to measure themselves. When someone says, “Be a man!” they typically evoke an ideal of masculinity which is dominant in that specific context. As Garlick (2010) argues, this ideal will change depending on the context but it always takes the same form:

the hegemonic form of masculinity in any particular social context is always the answer to a question—a question of what is needed to maintain control. The answer to this question, which will often involve some form of either physical strength or mental strength (e.g., violence or rationality), will depend on the historical, social, and cultural context in which it is asked. What is crucial is the belief that ‘‘to be a man’’ requires being in control; it is this contention itself that is hegemonic.

Hegemonic masculinity is paralleled by what Connell (1995) refers to as emphasized femininity. She argues that in a heteronormative and patriarchal society, the dominant styles of femininity are those which emphasize women’s compliance with their subordination to men including characteristics of supportiveness, nurturing, empathy, enthusiasm and sexual attractiveness.

Emphasized femininity values ways of expressing femininity that complement hegemonic heterosexual masculinity and therefore displaying traits that either challenge or mimic male dominance is often stigmatized. “Practices and characteristics that are stigmatized and sanctioned if embodied by women include having sexual desire for other women, being promiscuous, “frigid”, or sexually inaccessible, and being aggressive” (Schippers, 2007). On this basis, Schippers (2007) identifies a series of pariah femininities based on specific types of non-compliance: the lesbian who is attracted to women instead of men, the “bitch” who takes charge and challenges authority, the “bad-ass girl” who is physically violent, or the “slut” or “tease” who refuses exclusive sexual relationships with men or male control of their sexuality.

Gender Identity

Canadian society allows for some level of flexibility when it comes to acting out gender roles. To a certain extent, men can assume some feminine roles and characteristics and women can assume some masculine roles and characteristics without interfering with their gender identity. Gender identity is an individual’s self-conception of being male or female based on their association with masculine or feminine gender roles.

As opposed to cisgender individuals, who identify their gender with the gender and sex they were assigned at birth, individuals who identify with the gender that is the “opposite” of their biological sex are transgender. Transgender males, for example, are individuals who were assigned the sex ‘female’ at birth, but have such a strong emotional and psychological connection to the forms of masculinity in society that they identify their gender as male. The parallel connection to femininity exists for transgender females. It is difficult to determine the prevalence of transgenderism in society. Statistics Canada estimates that in 2018 approximately one million people were LGBTQ2+ in Canada, accounting for 4% of the total population aged 15 and older (Statistics Canada, 2021). Of these approximately 75,000 Canadians were trans or non-binary, representing 0.24% of the Canadian population aged 15 and older.

In the medical literature, transgender individuals who wish to alter their bodies through medical interventions such as surgery and hormonal therapy — so that their physical being is better aligned with their gender identity — are called transsex. They may also be known as male-to-female (MTF) or female-to-male (FTM) transsex. Gender terms are fluid however and many in the transgender community reject the historical term, transsexual, because of its history as medical or psychiatric label used to diagnose a mental illness. The term transsexual also implied a change in sexuality as opposed to gender or sex, which is misleading.

Devor’s (1997) accounts of female-to-male transsex indicate that the distinction between transgender individuals who undergo surgery and hormone therapy and those who do not is significant for self-identity however. Not all transgender individuals choose to alter their bodies: many will maintain their original physiology but may present themselves to society as the opposite gender. This is typically done by adopting the dress, hairstyle, mannerisms, or other characteristic typically assigned to the opposite gender. It is important to note that people who cross-dress, or wear clothing that is traditionally assigned to the opposite gender, are not necessarily transgender. Cross-dressing can also be a form of self-expression, entertainment, or personal style, not necessarily an expression of gender identity (APA, 2008).

There is no single, conclusive explanation for why people are transgender. Transgender expressions and experiences are so diverse that it is difficult to identify their origin. Some hypotheses suggest biological factors such as genetics, or prenatal hormone levels, as well as social and cultural factors, such as childhood and adulthood experiences. Most experts believe that all of these factors contribute to a person’s gender identity (APA, 2008).

It is known that transgender and transsex individuals experience discrimination based on their gender identity. People who identify as transgender are twice as likely to experience assault or discrimination as non-transgender individuals; they are also one and a half times more likely to experience intimidation (National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs, 2010; 2013). Organizations such as the Canadian Professional Association for Transgender Health (CPATH), Trans Pulse, and the National Center for Transgender Equality work to support and prevent, respond to, and end all types of violence against transgender, transsex, and homosexual individuals. These organizations hope that by educating the public about gender identity and empowering transgender and transsex individuals, this violence will end.

The Dominant Gender Schema

As sociological research points out, the naturalness with which one assumes a gender identity of being either masculine or feminine, or a sexual identity of being sexually attracted to either men or women, has a significant social component. Gender and sexual identities are deep identities in the sense that one does not seem to choose them. They appear to “come over” one, sometimes at a very early age, and thereafter appear for most people to be fixed. Nevertheless they are sustained by social norms and conventions. This social aspect of gender or sexual identity is revealed especially through the research tradition in sociology that focuses on those who break the rules of society. By studying those who break the rules, the rules themselves and what they entail become visible. In the study of gender and sexuality, the experience of intersexuals, transgender individuals, gays, lesbians, bisexuals, fetishists, and sexual “perverts,” etc. are invaluable for understanding what it means to have a gender or a sexuality. These individuals make up a minority of the population, but their lives and struggles reveal the existence of the social norms and processes of which others are often unaware.

Part of having a sexuality or a gender has to do with the “naturalness” with which an individual assumes one of the most fundamental identities that define their place in the world. However, having a gender or sexual identity only appears natural to the degree that one fits within the dominant gender schema (Devor, 2020). The dominant gender schema is an ideology that, like all ideologies, serves to perpetuate inequalities in power and status. This schema states that: a) sex is a biological characteristic that produces only two options, male or female, and b) gender is a social or psychological characteristic that manifests or expresses biological sex. Again, only two options exist, masculine or feminine: “All persons are either one gender or the other. No person can be neither. No person can be both. No person can change gender without major medical intervention” (Devor, 2020).

For many people this is natural. It “goes without saying.” However, if one does not fit within the dominant gender schema, then the naturalness of one’s gender identity is thrown into question. This occurs, first of all, by the actions of external authorities and experts who define those who do not fit as either mistakes of nature or as products of failed socialization and individual psychopathology. Gender identity is also thrown into question by the actions of peers and family who respond with concern or censure when a girl is not feminine enough or a boy is not masculine enough. Moreover, the ones who do not fit also have questions. They may begin to wonder why the norms of society do not reflect their sense of self, and thus begin to feel at odds with the world.

As the capacity to differentiate between the genders is the basis of patriarchal relations of power that have existed for 6,000 years, the dominant gender schema is one of the fundamental organizing principles that maintains the dominant societal order. Nevertheless, it is only a schema: a cultural pattern that is imposed upon the diversity of world. With respect to the biology of gender and sexuality, Anne Fausto-Sterling (2000) argues that a body’s sex is too complex to fit within the obligatory dual sex system, and ultimately, the decision to label someone male or female is a social decision.

Fausto-Sterling’s research on hermaphrodite or intersex children — the 1.7% of children born with a mixture of male and female sexual organs — indicates there are at least five different sexes:

- male;

- female;

- herms: true hermaphrodites with both male and female gonads (i.e., testes and ovaries);

- merms: male pseudo-hermaphrodites with testes and a mixture of sexual organs; and

- ferms: female pseudo-hermaphrodites with ovaries and a mixture of sexual organs.

Nevertheless, because assigning a sex identity is a fundamental cultural priority, doctors will typically decide “nature’s intention” with respect to intersex babies within 24 hours of an intersex child being born. Sometimes this decision involves surgery, which has scarred individuals for life (Fausto-Sterling, 2000).

Similarly, with respect to the variability of gender and sexuality, the experiences of gender and sexual outsiders — homosexuals, bisexuals, transgender people, women who do not look or act “feminine” and men who do not look or act “masculine,” etc. — reveal the subtle dramaturgical order of social processes and negotiations through which all gender identity is sustained and recognized by others (see the discussion of Erving Goffman’s dramaturgical analysis in Chapter 6. Social Interaction). Because one does not usually have the capacity to “look under the hood” to clinically determine the sex of someone one encounters, one reads their gender from their “gender display”— their “conventionalized portrayals” of the “culturally established correlates of sex” (Goffman, 1977). Gender is a performance which is enhanced by props like clothing and hairstyle, or mannerisms like tone of voice, physical bearing, and facial expression.

For a movie star like Marilyn Munroe, the gender display is exaggerated almost to the point of self-satire, whereas for gender blending women — women who do not dress or look stereotypically like women — the gender display can be (unintentionally) ambiguous to the point where they are often mistaken for men (Devor, 2020). The signs of gender need to be communicated in an unambiguous manner for an individual to “pass” as a member of their assigned gender. This is often a problem for transgender individuals and the cause of considerable stress and anxiety.

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

Intersexed Individuals and the Case of John/Joan

Part of the rationale of using surgery to “correct” the sexual ambiguity of intersex children is, firstly, the idea that not having a clear biological sex assignment will produce psychological pathology later in life. Secondly, the rationale is based on the idea that gender or sexual identity is fundamentally malleable (Fausto-Sterling, 2000). The practice is based on the logic of the nurture side of the long-standing debate about whether nature or nurture determines psycho-sexual development.

The nurture side argues that gender is neutral at birth and is subsequently molded by sex assignation and child-rearing (i.e., “environment”) into a stable gender identity as the child matures. This is the principle behind using surgery to modify indefinite sexual organs. It is understood that having an unambiguous penis or vagina is a clear symbolic marker of gender identity in one’s relationship to self and others. Whereas gender formation during childhood is malleable, gender ambiguity later in life is pathological and therefore surgery at an early age is required to avoid psychosexual problems in teenage and adult life.

The nature side, on the other hand, argues that gender is not neutral at birth. Gender is predetermined by the in utero hormonal processes that lead to the sexual development of the foetus. Even in intersex children, there is a distinct psychosexual predisposition to one gender or the other. Early in foetal development hormones act directly to organize the brain along gender lines, and the release of hormones at puberty produce sex-specific characteristics and behaviours.

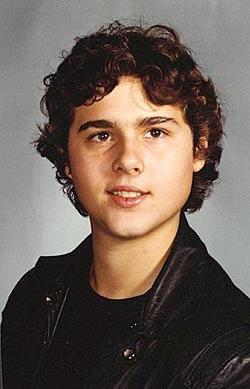

The life of David Reimer, known in the literature of the 1960s and 1970s as the John/Joan case, was used for many years as a demonstration of the validity of nurture arguments over nature arguments. In some respects it seemed like a perfect case to test the two propositions. David Reimer was born in Winnipeg, in 1965, as a male identical twin. However, as a result of a circumcision accident at age 7 months he lost his penis. Experts counseled that David should be surgically altered and raised as a girl. At age two David, known as “John” in the literature, had his testes removed and he became “Joan.” Her mother was cited in the literature as saying that Joan loved wearing dresses, hated getting dirty, and enjoyed having her hair set. As Joan’s biologically identical male twin continued to mature in a manner typical to boys, it seemed to demonstrate the dominant influence of gendered patterns of child-rearing on the formation of gender identity. Joan was being raised as a girl, her male sex organs had been surgically altered, and her transition from boy to girl seemed unproblematic. From the point of view of the nurture side of the debate, the case demonstrated that gender identity was primarily learned (Fausto-Sterling, 2000).

However, in 1980, a BBC documentary doing a follow up on the famous case discovered that by the time Joan was thirteen she was not well adjusted to her sex assignment (Fausto-Sterling, 2000). She peed standing up, walked like a boy, wanted to be a mechanic and thought boys had better lives than girls. Eventually it came out that she had eventually had her breasts removed, had a surgically reconstructed penis implanted, and had married a woman and was fathering his wife’s child. Contradicting the original findings, John/Joan’s mother reported that Joan had consistently resisted attempts to socialize her as a girl. Sadly, following a period of severe depression, David Reimer killed himself at the age of 38. The failure of the sex reassessment lent credence to the nature side of the debate. It seemed to demonstrate that humans are not psycho-sexually neutral at birth, but are biologically predisposed to behave in a male or female manner.

The literature is not conclusive. There have been other reports of individuals in similar circumstances rejecting their sex assignments but in the case of another Canadian child whose sex reassessment occurred at seven months, much earlier than David Reimer’s, gender identity was successfully changed (Bradley et. al., 1998). Nevertheless, while this subject identified as a female, she was a tomboy during childhood, worked in a blue-collar masculine trade, did have love affairs with men but at the time of the report was living as a lesbian. The authors argue that her gender identity was successfully changed through surgery and socialization, even if her gender role and sexual orientation were not.

Fausto-Sterling’s (2000) conclusion is that gender and sex are fundamentally complex and that it is not a simple question of either nurture or nature being the determinant factor. This complexity has practical implications for how to respond to the birth of intersex children. In particular, she outlines practical medical ethics for children whose sex is ambiguous:

- Let there be no unnecessary infant surgery: do no harm;

- Let physicians assign a provisional sex based on known probabilities of gender identity formation; and

- Provide full information and long-term counseling to the parents and child.

Fausto-Sterling argues that it is important to recognize the variability of sex and gender beyond the two-sex system.

Image Descriptions

| Feminine Items |

Masculine Items |

Neutral Items |

|---|---|---|

| Affectionate | Defends own beliefs | Adaptable |

| Understanding | Strong personality | Conventional |

| Warm | Willing to take risks | Helpful |

| Gentle | Aggressive | Likable |

| Soft-spoken | Analytical | Secretive |

| Childlike | Individualistic | Tactful |

| Sympathetic | Ambitious | Unpredictable |

| Compassionate | Independent | Conceited |

| Tender | Forceful | Friendly |

| Yielding | Dominant | Inefficient |

| Flatterable | Self-reliant | Moody |

| Gullible | Self-sufficient | Sincere |

| Feminine | Masculine | Theatrical |

| Sensitive to the needs of others | Act as a leader | Unsystematic |

| Eager to soothe hurt feelings | Assertive | Conscientious |

| Loves children | Has leadership abilities | Happy |

| Cheerful | Willing to take a stand | Jealous |

| Loyal | Athletic | Reliable |

| Does not use harsh language | Makes decisions easily | Solemn |

| Competitive | Truthful [Return to Figure 12.7] |

Media Attributions

- Figure 12.3 Man and woman silhouettes by Tournai, Belgique is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 12.4 Catlin – Dance to the berdache by George Catlin (1796–1872), via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 12.5 Vancouver – law courts pano 01 by Joe Mabel, via OpenVerse, is used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 licence.

- Figure 12.6 Kinsey Scale by Justin Anthony Knapp, based on Kinsey’s Sexual Behavior in the Human Female (1953). This image is made available under the CC0 1.0 public domain licence.

- Figure 12.7 The Bem Sex-Role Inventory (or BSRI), from Open Access copy of Schiappa (2022) The Transgender Exigency (p. 18), Taylor & Francis, is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 licence.

- Figure 12.8 Bruce Lee from the film Fists of Fury (aka The Big Boss) by National General Pictures, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 12.9 A transgender woman standing at a bar with her hand under her chin by Zackary Drucker, via the Gender Spectrum Collection from Broadly [now VICE] is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 licence.

- Figure 12.10 The jet set! by RomitaGirl67, via OpenVerse, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 12.11 Marilyn Monroe in November 1953 by Bert Parry, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 12.12 David Reimer by unknown is used under the fair dealing exception in the Canadian Copyright Act and fair use under US copyright law.