Chapter 12. Gender, Sex, and Sexuality

12.2 Gender and Society

The organization of society is profoundly gendered, meaning that the “natural” distinction between male and female, and the attribution of different qualities to each, underlies institutional structures from the family, to the occupational structure, to the division between public and private, to access to power and beyond. Patriarchy is the set of institutional structures (like property rights, access to positions of power, and relationship to sources of income) which are based on the belief that men and women are dichotomous and unequal categories. How does the “naturalness” of the distinction between male and female get established? What are its consequences for power relationships? How does it serve to organize everyday life?

Gender and Socialization

The phrase “boys will be boys” is often used to justify behaviour such as pushing, shoving, or other forms of aggression from young boys. The phrase implies that such behaviour is unchangeable and something that is part of a boy’s nature. Aggressive behaviour, when it does not inflict significant harm, is often accepted from boys and men because it is congruent with the cultural script for masculinity. The “script” written by society is in some ways similar to a script written by a playwright. Just as a playwright expects actors to adhere to a prescribed script, society expects women and men to behave according to the expectations of their respective gender role. Scripts are generally learned through the process of socialization, which teaches people to behave according to social norms.

Role learning starts with socialization at birth. Children learn at a young age that there are distinct expectations for boys and girls. Even today, people are quick to outfit male infants in blue and girls in pink, even applying these colour-coded gender labels while a baby is in the womb. Cross-cultural studies reveal that children are aware of gender roles by age two or three. At four or five, most children are firmly entrenched in culturally appropriate gender roles (Kane, 1996). Children acquire these roles through socialization, a process in which people learn to behave in a particular way as dictated by societal values, beliefs, and attitudes. For example, society often views riding a motorcycle as a masculine activity and, therefore, considers it to be part of the male gender role. Attitudes such as this are typically based on stereotypes — oversimplified notions about members of a group. Gender stereotyping involves overgeneralizing about the attitudes, traits, or behaviour patterns of women or men. For example, women may be thought of as too timid or weak to ride a motorcycle.

One way children learn gender roles is through play. Parents typically supply boys with trucks, toy guns, and superhero paraphernalia, which are active toys that promote motor skills, aggression, and solitary play. Girls are often given dolls and dress-up apparel, which are toys that foster nurturing, social proximity, and role play. Studies have shown that children will most likely choose to play with “gender appropriate” toys (or same-gender toys) even when cross-gender toys are available because parents give children positive feedback (in the form of praise, involvement, and physical closeness) for gender-normative behaviour (Caldera, Huston, and O’Brien, 1998). Sociologists are therefore interested in the ways that children learn to do gender, rather than seeing gender roles as predetermined by biology. There is considerable variation in the performance of gender roles within and across cultures, which indicates that they have a social explanation. See Chapter 5. Socialization for further elaboration on the socialization of gender roles.

Gender stereotypes also form the basis of sexism. Sexism refers to prejudiced beliefs that value one sex over another. Sexism varies in its level of severity. In parts of the world where women are strongly undervalued, young girls may not be given the same access to nutrition, health care, and education as boys. Furt–her, they will grow up believing they deserve to be treated differently from boys (Thorne, 1993; UNICEF, 2007). While illegal in Canada when practiced as discrimination, unequal treatment of women continues to pervade social life. It should be noted that discrimination based on sex occurs at both the micro- and macro-levels. Many sociologists focus on discrimination that is built into the social structure; this type of discrimination is known as institutional discrimination (Pincus, 2008).

Gender socialization occurs through four major agents of socialization: family, education, peer groups, and mass media. Each agent reinforces gender roles by creating and maintaining normative expectations for gender-specific behaviour. Exposure also occurs through secondary agents such as religion and the workplace. Repeated exposure to these agents over time leads men and women into a false sense that they are acting naturally rather than following a socially constructed role.

Family is the first agent of socialization. There is considerable evidence that parents socialize sons and daughters differently. Generally speaking, girls are given more latitude to step outside of their prescribed gender role (Coltrane and Adams, 2004; Kimmel, 2000; Raffaelli and Ontai, 2004). However, differential socialization typically results in greater privileges afforded to boys. For instance, sons are allowed more autonomy and independence at an earlier age than daughters. They may be given fewer restrictions on appropriate clothing, dating habits, or curfew. Sons are also often free from performing domestic duties such as cleaning or cooking, and other household tasks that are considered feminine. Daughters are limited by their expectation to be passive, nurturing, and generally obedient, and to assume many of the domestic responsibilities. They do not get the same opportunities as boys to work with tools or engage in physical activities and sports regarded as rough or dangerous.

Even when parents set gender equality as a goal, there may be underlying indications of inequality. For example, when dividing up household chores, boys may be asked to take out the garbage or perform other tasks that require strength or toughness, while girls may be asked to fold laundry or perform duties that require neatness and care. It has been found that fathers are firmer in their expectations for gender conformity than are mothers, and their expectations are stronger for sons than they are for daughters (Kimmel, 2000). This is true in many types of activities, including preference of toys, play styles, discipline, chores, and personal achievements. As a result, boys tend to be particularly attuned to their father’s disapproval when engaging in an activity that might be considered feminine, like dancing or singing (Coltrane and Adams, 2008). It should be noted that parental socialization and normative expectations vary along lines of social class, race, and ethnicity. Research in the United States has shown that African American families, for instance, are more likely than whites to model an egalitarian gender role structure for their children (Staples and Boulin Johnson, 2004).

The reinforcement of gender roles and stereotypes continues once a child reaches school age. Until very recently, schools were rather explicit in their efforts to segregate and stratify boys and girls. Girls were encouraged to take home economics or humanities courses and boys to take shop, math, and science courses. Segregation and stratification has also been reinforced in learning materials. Quantitative textual analysis of gender stereotyping in elementary school textbooks in the 1970s also revealed “shocking evidence of various other kinds of rigid stereotyping and of racism” (Priegert Coulter, 1996). Observing the number of times women and men appeared in textbooks, and in what types of work and family roles, indicated that none of the curriculum could be regarded as “positive image” or “non-biased.” By the late 1980s, provincial education policy had established guidelines to remove gender bias in learning materials but children’s books still under-represent female characters or present them in stereotypical roles (more emotional, less active, and less associated with science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) subjects), while generally omitting role models outside the gender binary (Casey et al., 2021).

Studies suggest that gender socialization still occurs in schools today, perhaps in less obvious forms (Lips, 2004). Teachers may not even realize that they are acting in ways that reproduce gender-differentiated behaviour patterns. Typically this occurs in three ways. Firstly, teachers themselves are gender role models and can reinforce gender stereotypes by their own behaviour, for example, female teacher’s who exhibit “math phobias. Secondly, teachers often display different expectations for male and female students. Thirdly, teachers reinforce gender biases by using gender distinctions to catgorize and organize students and student activities. Any time they ask students to arrange their seats or line up according to gender, teachers are asserting that boys and girls should be treated differently (Thorne, 1993).

Even in levels as low as kindergarten, schools subtly convey messages to girls indicating that they are less intelligent or less important than boys. For example, in a study involving teacher responses to male and female students, data indicated that teachers praised male students far more than their female counterparts. Additionally, teachers interrupted girls more and gave boys more opportunities to expand on their ideas (Sadker and Sadker, 1994). Further, in social as well as academic situations, teachers have traditionally positioned boys and girls oppositionally — reinforcing a sense of competition rather than collaboration (Thorne, 1993). Boys are also permitted a greater degree of freedom regarding rule-breaking or minor acts of deviance, whereas girls are expected to follow rules carefully and to adopt an obedient posture (Reay, 2001). Schools reinforce the polarization of gender roles and the age-old “battle of the sexes” by positioning girls and boys in competitive arrangements.

In the case of peer group influences on gender, mimicking the actions of significant others is the first step in the development of a separate sense of self (Mead, 1934). Like adults, children become agents who actively facilitate and apply normative gender expectations to those around them. When children do not conform to the appropriate gender role, they may face negative sanctions such as being criticized or marginalized by their peers. Though many of these sanctions are informal, they can be quite severe. For example, a girl who wishes to play hockey instead of dance lessons may be called a “tomboy” and face difficulty gaining acceptance from both male and female peer groups (Reay, 2001). Boys, especially, are subject to intense ridicule for gender nonconformity (Coltrane and Adams, 2008; Kimmel, 2000).

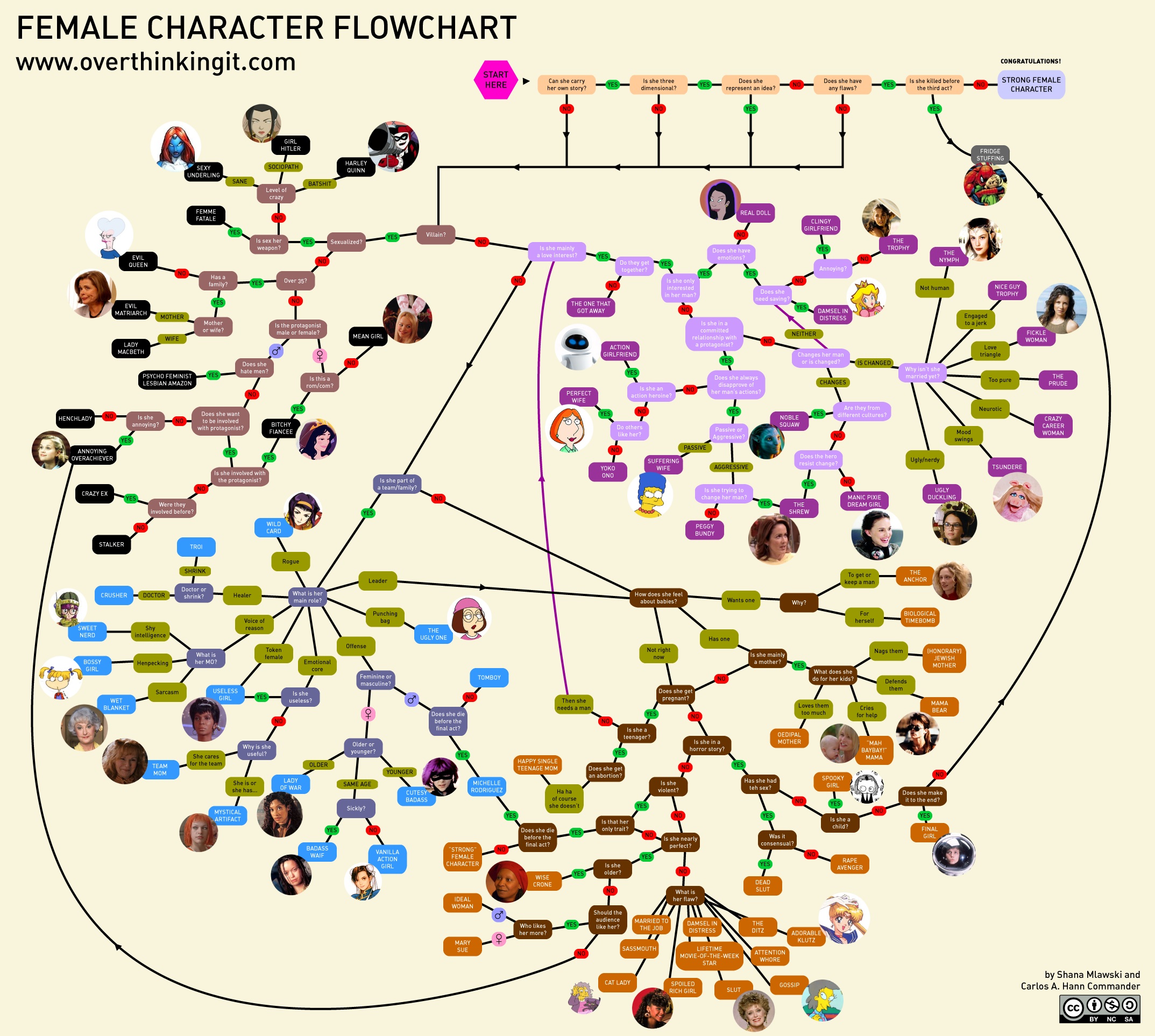

Mass media serves as another significant agent of gender socialization. In television and movies, women tend to have less significant roles and are often portrayed as wives or mothers. When women are given a lead role, they are often one of two extremes: a wholesome, saint-like figure or a malevolent, hypersexual figure (Etaugh and Bridges, 2003). This same inequality is pervasive in children’s movies (Smith, 2008). Research indicates that of the 101 top-grossing G-rated movies released between 1990 and 2005, three out of four characters were male. Out of those 101 movies, only seven were near being gender balanced, with a character ratio of less than 1.5 males per 1 female (Smith, 2008).

Television commercials and other forms of advertising also reinforce inequality and gender-based stereotypes. Women are almost exclusively present in ads promoting cooking, cleaning, or child care-related products (Davis, 1993). Think about the last time one saw a man star in a dishwasher or laundry detergent commercial. In general, women are underrepresented in roles that involve leadership, intelligence, or a balanced psyche. Of particular concern is the depiction of women in ways that are dehumanizing, especially in music videos. Even in mainstream advertising, however, themes intermingling violence and sexuality are quite common (Kilbourne, 2000).

Social Stratification and Inequality

How do the distinctions between male and female, and the social attribution of different qualities to each, serve to organize our institutions (the family, occupational structure, and the public/private divide, etc.)? How do these distinctions organize differential access to rewards, privileges, and power? In society, how and why are women not treated as the equals of men?

Stratification refers to a system in which groups of people experience unequal access to basic, yet highly valuable, social resources. According to George Murdock’s classic work, Outline of World Cultures (1954), all societies classify work by gender. When a pattern appears in all societies, it is called a cultural universal. While the phenomenon of assigning work by gender is universal, its specifics are not. The same task is not assigned to either men or women worldwide. But the way each task’s associated gender is valued is notable. In Murdock’s examination of the division of labour among 324 societies around the world, he found that in nearly all cases the jobs assigned to men were given greater prestige (Murdock and White, 1969). Even if the job types were very similar and the differences slight, men’s work was still considered more vital.

Canadian society is also characterized by gender stratification. Evidence of gender stratification is especially keen within the economic realm. In Canada, women’s experience with wage labour includes unequal treatment in comparison to men in many respects:

- Women continue to do more of the unpaid labour in the household — meal preparation and cleanup, childcare, elderly care, household management, and shopping — even if they have a job outside the home. In 2010, women spent an average 50 hours a week looking after children compared to 24.4 hours a week for men, 13.8 hours a week doing household work compared to 8.3 hours for men, and, of those caring for elderly family members, 49% of women spent more than 10 hours a week caring for a senior compared to 25% for men (Statistics Canada, 2011. This double duty keeps working women in a subordinate role in the family structure and prevents them from achieving the salaries of men in the paid workforce (Hochschild and Machung, 1989).

- Women’s participation in the labour force has been increasing from 42% of women in 1976 to 58% of women in 2009 (Statistics Canada, 2011). Women now make up 48% of the total labour force (compared to 37% in 1976). They continue to dominate in “pink collar” occupations and part-time work, which are low paying, low status, often unskilled jobs that offer little possibility for advancement. In 2009, 67% of women still worked in traditionally “feminine” occupations like teaching, nursing, clerical, administrative or sales, and service jobs. 70% of part-time workers and 60% of minimum wage workers were women (Ferrao, 2010).

- Despite women making up nearly half (48%) of payroll employment, men vastly outnumber them in authoritative, powerful, and, therefore, high-earning jobs (Statistics Canada, 2011). Women’s income for full-year, full-time workers has remained at 72% of the income of men since 1992. This in part reflects the fact that women are more likely than men to work in part-time or temporary employment. The comparison of average hourly wage is better: Women earned 83% of men’s average hourly wage in 2008, up from 76% in 1988 (Statistics Canada, 2011; see Statistics Canada, 2018, for a more updated report). However, as one report noted, if the gender gap in wages continues to close at the same glacial rate, women will not earn the same as men until the year 2240 (McInturff, 2013).

The reason for the gender gap in wages is fourfold. Firstly, there is gender discrimination in hiring and salary. Women and men are often not rewarded equally for the same work despite the fact discrimination on the basis of sex is unconstitutional in Canada. Secondly, as noted above, men and women tend to be concentrated in different types of work which are not equally paid. Often because of choices made in high school and postsecondary education, women are limited to pink collar types of occupation. Thirdly, the unequal distribution of domestic duties, especially child and elder care, women are unable to work the same number of hours as men and experience disruptions in their career path. Fourthly, the work typically done by women is arbitrarily undervalued with respect to the work typically performed by men. It is certainly questionable that early childhood education occupations dominated by women involve less skill, less training, or less significance to society than many occupations dominated by men like tech support or construction, but there is a clear disparity in wages between these typically gender segregated types of occupation.

One way in which gender roles affect women’s access to higher paying jobs and leadership positions is the glass ceiling phenomenon. Whereas most of the explicit barriers to women’s achievement have been removed through legislative action, norms of gender equality, and affirmative action policies, women often get stuck at the level of middle management. There is a glass ceiling or invisible barrier that prevents them from achieving positions of leadership (Tannen, 1994). This is also reflected in gender inequality in income over time.

Early in their careers men’s and women’s incomes are more or less equal but at mid-career, the gap increases significantly (McInturff, 2013).

Tannen (1994) argues that this barrier exists in part because of the different work styles of men and women, in particular conversational-style differences. Whereas men are very aggressive in their conversational style and their self-promotion, women are typically consensus builders who seek to avoid appearing bossy and arrogant. As a communicative strategy of office politics, it is common for men to say “I” and claim personal credit in situations where women would be more likely to use “we” and emphasize teamwork. As it is men who are often in the positions to make promotion decisions, they interpret women’s style of communication “as showing indecisiveness, inability to assume authority, and even incompetence”

(Tannen, 1994).

Beyond the economic sphere, there has been a long history of power relations based on gender in Canada. When looking to the past, it would appear that society has made great strides in terms of abolishing some of the most blatant forms of gender inequality (see timeline below) but the underlying effects of male dominance still permeate many aspects of society. The issue remains especially pertinent with regard to political representation. As elected representatives, the ratio of women to men in federal parliament and provincial legislatures is about 1 in 4, or 25% (McInturff, 2013).

- Before 1859 — Married women were not allowed to own or control property

- Before 1909 — Abducting a woman who was not an heiress was not a crime

- Before 1918 — Women were not permitted to vote (propertied women’s right to vote was taken away in New France in 1849)

- Before 1929 — Women were not legally considered “persons”

- Before 1953 — Employers could legally pay a woman less than a man for the same work

- Before 1969 — Women did not have the right to a safe and legal abortion (Nellie McClung Foundation, N.d.)

Making Connections: Sociological Research

Is the Patriarchy Dead?

It is becoming more common to hear post-feminist arguments that in liberal democracies like Canada, the war against patriarchy (i.e., male rule) has more or less been won. The days in which women were not permitted to work or hold a credit card in their own name are over. Today women are working outside the home more than ever, they are narrowing the wage gap with men (albeit slowly), and they are surpassing men in getting university degrees. They are now as free as men to have a credit card and get into debt. These arguments are more complicated than the post-feminist slogan “patriarchy is dead” suggests, but it is clear that the question of gender inequality is more ambiguous than it once was.

| Year | Total Percentage of Men’s Wages | Women Aged 25 to 29 years | Women Aged 30 to 34 years | Women Aged 35 to 39 years | Women Aged 40 to 44 years | Women Aged 45 to 49 years | Women Aged 50 to 54 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1988 | 0.757 | 0.846 | 0.794 | 0.768 | 0.736 | 0.681 | 0.645 |

| 1993 | 0.794 | 0.905 | 0.886 | 0.772 | 0.762 | 0.700 | 0.709 |

| 1998 | 0.811 | 0.901 | 0.851 | 0.805 | 0.808 | 0.750 | 0.749 |

| 2003 | 0.825 | 0.920 | 0.868 | 0.843 | 0.804 | 0.768 | 0.771 |

| 2008 | 0.833 | 0.901 | 0.858 | 0.837 | 0.825 | 0.784 | 0.807 |

| Difference from 1988 to 2008 | 0.076 | 0.056 | 0.064 | 0.068 | 0.089 | 0.103 | 0.162 |

Source (Statistics Canada, 2011, p 166)

As noted above, women’s annual income (for full-time employees) remains at 72% of that earned by men. However, this figure is misleading because it does not take into account that men on average work 3.7 hours more a week than women (Statistics Canada, 2011, p. 166-167). Table 12.1 compares men’s and women’s hourly wage and shows that between 1988 and 2008, the wage gap has narrowed for each of the age groups. On average, women went from earning 76% of men’s hourly wage to 83%. Young women ages 25 to 29 now earn 90% of young men’s hourly wage. As the Statistics Canada report says, “younger women are more likely to have high levels of education, work full-time, and be employed in different types of jobs than their older female counterparts” (Statistics Canada, 2011), which accounts for the difference between the age groups.

However, is this a good news story? First, the difference between the 72% figure (gender difference in annual income) and the 83% figure (gender difference in hourly wage) reveals, for reasons which are unclear from the statistics, that women are not working in occupations that pay as well or offer as many hours of work per week as men’s occupations. Second, the gender gap is closing in large part because men’s wages have remained flat or decreased. In particular, young men who worked traditionally in high paying manufacturing jobs have seen declines in union coverage and real wages (Drolet, 2011, p. 8). Third, even though young women have higher levels of education than young men, and even though they choose to work in higher paying jobs in education and health than previous generations of women, they still earn 10% less per hour than young men. That is still a substantial difference in wages that is unaccounted for. Fourth, the real problem is that although men and women increasingly begin their careers on equal footing, by mid-career, when workers are beginning to maximize their earning potential, women fall behind and continue to do so into retirement. Why?

Theoretical Perspectives on Gender

Sociological theories serve to guide the research process and offer a means for interpreting research data and explaining social phenomena. For example, a sociologist interested in gender stratification in education may study why middle-school girls are more likely than their male counterparts to fall behind grade-level expectations in math and science. Another sociologist might investigate why women are underrepresented in political office, while another might examine how women in corporate management are treated by their male counterparts in meetings. Positivist approaches seek to establish and explain law-like relationships between variables. Structural functionalists, for example, examine gendered social roles and norms as products of the functional requirements of institutions. Critical sociology focuses on the power relationships that create and reproduce inequalities between the genders, whereas interpretive sociology examines how meanings and inferences about gender differences are established and circulate in society. Each type of theory provides a different angle for sociologists to pursue their research.

Structural Functionalism

Structural functionalism provided one of the most important perspectives of sociological research in the 20th century and has been a major influence on research in the social sciences, including gender studies. Viewing the family as the most integral component of society, assumptions about the complementarity of gender roles within marriage assume a prominent place in this perspective.

Functionalists argue that complementary gender roles were established well before the preindustrial era when men typically took care of responsibilities outside of the home, such as hunting, hard physical labour, and combat, and women typically took care of the domestic responsibilities in or around the home. These roles are considered functional because women were frequently limited by the physical restraints of pregnancy and nursing, and unable to leave the home for long periods of time. Men were less limited. Once established, these roles were passed on to subsequent generations since they served as an effective means of keeping the family system functioning properly.

Jumping forward to the modern era, gender roles began to change. Norms of equality, established in the democratic revolutions of the 18th century, began to be extended to women and other subordinate groups. The transition from feudalism to industrial capitalism reduced the size of families and the economic importance of the family as a unit. Social and economic changes in Canada during and after World War II, produced further changes in the family structure. During the war, many women had to assume the role of breadwinner alongside their domestic role in order to stabilize the wartime society. This created a tension following WWII when men returned from war and wanted to reclaim their civilian jobs. Many women did not want to forfeit the independence that came with their wage-earning positions (Hawke, 2007). In the 1960s as Canadian society shifted from a Fordist to post-Fordist economy, and from the welfare state to neoliberalism, it became increasing difficult for families to survive on the wages of a single breadwinner and the majority of women entered the workforce permanently. From the point of view of structural functionalism, where every component of the social system as a whole is interrelated, these changes were interpreted as a source of societal imbalance that had ramifications throughout society.

For example, Talcott Parsons (1958) argued that the contradiction between occupational roles and kinship roles of men and women in North America created tension or strain on individuals as they tried to adapt to the conflicting norms or requirements. The division of traditional middle-class gender roles within the family — the husband as breadwinner and wife as homemaker — was functional for him because the roles were complementary. They enabled a clear division of labour between spouses, which ensured that the ongoing functional needs of the family were being met. Within the North American kinship system, wives and husbands’ roles were equally valued according to Parsons. However, within the occupational system, only the husband’s role as breadwinner was valued. There was an “asymmetrical relation of the marriage pair to the occupational structure.” Being barred from the occupational system meant that women had to find a functional equivalent to their husbands’ occupational status to demonstrate their “fundamental equality” with their husbands. As a result, Parson theorized that these tensions would lead women to become expressive specialists in order to claim social prestige (e.g., showing “good taste” in appearance, household furnishings, literature, and music), while men would remain instrumental or technical specialists and become culturally narrow. He also proposed that the instability of the female role in this system would lead to excesses in women like neuroses, compulsive domesticity, garishness in taste, disproportionate attachment to community activities, and the “glamour girl” pattern: “the use of specifically feminine devices as an instrument of compulsive search for power and exclusive attention” (Parsons, 1943).

Contemporary functionalism asks how new forms of stable equilibrium are created in society when gender roles and family structures have become more fluid.

Critical Sociology

According to critical sociology, society is structured by relations of power and domination among social groups including genders that determine access to scarce resources. When sociologists examine gender from this perspective, they can view men as the dominant group and women as the subordinate group. According to critical sociology, social problems and contradictions are created when dominant groups exploit or oppress subordinate groups. Consider the women’s suffrage movement or the debate over women’s “right to choose” their reproductive futures. Even in societies with norms and laws supporting gender equality, it is difficult for women to rise to equality with men, as dominant group members create the rules for success and opportunity in society (Farrington and Chertok, 1993). The glass ceiling phenomenon discussed above is an example.

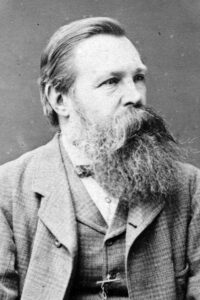

Friedrich Engels (1884) studied family structure and gender roles in the 1880s in the historical context of the development of capitalism. Engels showed that the transition from the household, as the site of production under feudalism, to the capitalist workplace separate from the household lead to a double exploitation of women. The same exploitative owner-worker relationship seen in the labour force is seen in the household, with women assuming the role of the household proletariat. Women’s unpaid domestic labour supports not only the household itself (and the raising of new workers), but the ability of their male partners, (and increasingly their own), to provide labour to employers. Women are therefore doubly exploited in capitalist society: both when they work outside the home and when they work within the home. This is due to women’s dependence on men for the attainment of wages, which is even more constraining for women who are entirely dependent upon their spouses for economic support. Contemporary critical sociologists suggest that when women become wage earners, they can gain power in the family structure and create more democratic arrangements in the home, although they may still carry the majority of the domestic burden, as noted earlier (Risman and Johnson-Sumerford, 1998).

Feminist Theory

Feminist theory is a type of critical sociology that examines inequalities in gender-related issues. It also uses the critical approach to examine the maintenance of gender roles and inequalities. Radical feminism, in particular, considers the role of the family in perpetuating male dominance. In patriarchal societies, men’s contributions are seen as more valuable than those of women. Women are essentially the property of men. Through the feminist struggles for women’s emancipation in post-feudal modern society, the property relationship has been formally eliminated. Nevertheless, women still tend to be relegated to the private sphere, where domestic roles define their primary status identity. Men’s roles and primary status continues to be largely defined by their activities in the public or occupational sphere.

As a result, women often perceive a disconnect between their personal experiences and the way the world is represented by society as a whole. Dorothy Smith referred to this phenomenon as bifurcated consciousness (Smith, 1987). There is a division between the directly lived, bodily experience of women’s worlds (e.g., their responsibilities for looking after children, aging parents, and household tasks) and the dominant, abstract, institutional world to which they must adapt (the work and administrative world of bureaucratic rules, documents, and cold, calculative reasoning). Modrn society situates women in a world where there are two modes of knowing, experiencing, and acting that are directly at odds with one another (Smith, 2008). Patriarchal perspectives and arrangements, widespread and taken for granted, are built into the relations of ruling. As a result, not only do women find it difficult to see their experiences acknowledged in the wider patriarchal culture, their viewpoints also tend to be silenced or marginalized to the point of being discredited or considered invalid.

Sanday’s study of the Indonesian Minangkabau (2004) revealed that in societies that some consider to be matriarchies (where women are the dominant group), women and men tend to work cooperatively rather than competitively, regardless of whether a job is considered feminine by North American standards. The men, however, do not experience the sense of bifurcated consciousness under this social structure that modern Canadian females encounter (Sanday, 2004).

For feminist scholars of the 1970s and 1980s, the point of identifying gender norms and social conventions was to undercut their cultural force—to free people from behavioral and social expectations that were based on their biological sex. For some gender nonconformists, traits traditionally identified as masculine or feminine are accepted as masculine or feminine,

but nonconformists want the freedom to express their gender with whatever combination of traits they choose. For example, a person can present as a “femme” transgender woman and still consider themselves as nonbinary (Williams 2019). Moreover, any particular gender identity can be ephemeral—that is, transitory and temporary—as opposed to an enduring commitment.

For some gender nonconformists the very idea of “gender” seems obsolete and society should embrace postgenderism. Shulamith Firestone advocated the spirit of postgenderism even before “gender” entered the vocabulary of feminist politics. She wrote in 1970 that, “[The] end goal of feminist revolution must be, unlike that of the first feminist movement, not just the elimination of male privilege but of the sex distinction itself: genital differences between human beings would no longer matter culturally” (Firestone, 1970). Similarly, though Sandra Bem did not use the term “post-gender,” in hindsight it seems fair to describe her dream as a postgender society: “[H]uman behaviors and personality attributes should no longer be linked to gender, and society should stop projecting gender into situations irrelevant to genitalia” (Bem, 1983).

Note: The last two paragraphs have been adapted from from , 2021, The Transgender Exigency: Defining Sex and Gender in the 21st Century, Routledge. Used under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/) license.

Interpretive Sociology and Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic interactionism aims to understand human behaviour by analyzing the central role of symbols in human interaction. Establishing the meaning of symbols creates a common “definition of the situation” which enables coordinated activities to be carried out. This is certainly relevant to the discussion of masculinity and femininity. As noted earlier, people are rarely given the opportunity in social interactions to clinically determine the sex of the people they are interacting with. Sex is typically “read off” of gender displays and gestures such as clothing, jewelry, makeup, hair style, mannerisms, role performance, tone of voice, etc. and then judgements are made about how feminine or how masculine the person is that affect how the interaction unfolds. Gender is typically perceived through signs, displays and gender performances. When people perform tasks or possess characteristics based on the gender role assigned to them, they are said to be doing gender (West and Zimmerman, 1987). Whether a person is expressing their masculinity or femininity, West and Zimmerman argue, they are always “doing gender.” Thus, gender is something a person does, signals or performs, not something they are.

Sociologist Charles H. Cooley’s concept of the “looking-glass self” (1902) is also relevant here (see Chapter 5. Socialization). Cooley suggests that one’s determination of self is based mainly on the view of others in society (for instance, if other people perceive a man as masculine, then that man will perceive himself as masculine). In other words, one interiorizes an image of oneself as male, female, or non-binary based on the ongoing reactions or judgements of others.

Because the meanings attached to symbols are socially created and not natural, and fluid, not static, people act and react to symbols based on the current assigned meaning. For example, in Gutmann’s study of machismo in contemporary Mexico City, he notes that the use of the term “machismo” for the stereotypical virile, aggressive, intransigent, hyper-masculine “macho” male has a relatively recent history, coming into usage in the early mid-20th century through the emergence of the Mexican film industry and the consolidation of the Mexican nation-state. Older men he interviewed in the poor district of Colonia Santo Domingo tended to divide males into machos (honourable men who looked after their families) and mandilones (female-dominated men), but they felt that the true macho men of the past were a disappearing type. Younger men in the district tended to regard the term macho pejoratively, as not worthy of emulation. They characterized themselves as “non-macho,” neither-macho-nor-mandilón. “For these younger men, then, the present period is distinguished by its liminal character with respect to male gender identities: as neither-macho-nor-mandilón, these men are precisely betwixt and between assigned cultural positions” (Gutmann, 2007).

These shifts in symbolic meaning apply to family structure as well. In 1976, when only 27.6% of married women with preschool-aged children were part of the paid workforce, a working mother was still considered an anomaly and there was a general view that women who worked were “selfish” and not good mothers. Today, a majority of women with preschool-aged children are part of the paid workforce (66.5%), and a working mother is viewed as normal (Statistics Canada, 2011). The working mother is not only the product of economic necessity, as critical sociologists have argued, but of the communicative processes that have lead to a general societal consensus on the changing meaning of a “good mother.”

Nevertheless, the conceptual opposition between male and female, and the privileging of masculine over feminine qualities, is remarkably enduring in Western culture. Interpretive sociologists influenced by the study of semiotics — the science of signs — point to deep and often hidden or unconscious structures of language that take the form of binary oppositions to explain this. Binary oppositions are paired terms like male/female, rationality/emotion, mind/body, culture/nature, black/white, etc. that carry opposed or opposite meanings. Logically, the meaning of something becomes clearer if what it does not mean can be determined. Binary pairs, particularly binary opposites, form the elementary structure of meaning in all human signifying systems, yet there are no binary relations in nature, only in culture. It is a scheme imposed on nature. Observable differences between males and females are translated into conceptual opposites, not because of any inherent properties each might have, but only because they are conceptually opposed. Similarities are discarded.

An example of this is the phrase “men are from Mars, women are from Venus” used in pop psychology. Ideas of men and women being complete opposites invite simplistic comparisons that rely on stereotypes: men are practical, women are emotional; men are strong, women are weak; men lead, women support. Binary notions seem to be built into the language a society uses to communicate, but they mask complicated realities and variety in the realm of social identity. They also erase the existence of individuals, such as multiracial or mixed-race people and people with non-binary gender identities, who may identify with neither of the assumed categories or with multiple categories.

Making Connections: Sociological Research

Being Male, Being Female, and Being Healthy

In 1971, Broverman and Broverman conducted a groundbreaking study on the traits mental health workers ascribed to males and females. When asked to name the characteristics of a female, the list featured words such as unaggressive, gentle, emotional, tactful, less logical, not ambitious, dependent, passive, and neat. The list of male characteristics featured words such as aggressive, rough, unemotional, blunt, logical, direct, active, and sloppy (Seem and Clark, 2006). Later, when asked to describe the characteristics of a healthy person (not gender-specific), the list was nearly identical to that of a male.

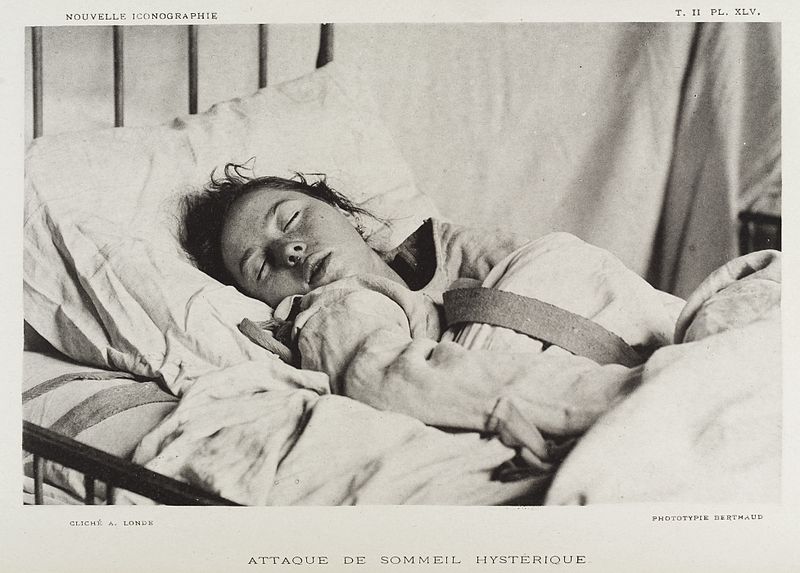

This study uncovered the general assumption that being female is associated with being somewhat unhealthy or not of sound mind. This concept seems extremely dated, but in 2006, Seem and Clark replicated the study and found similar results. Again, the characteristics associated with a healthy male were very similar to that of a healthy (genderless) adult. The list of characteristics associated with being female broadened somewhat but did not show significant change from the original study (Seem and Clark, 2006). This interpretation of feminine characteristics may help us one day to better understand gender disparities in certain illnesses, such as why one in eight women can be expected to develop clinical depression in her lifetime (National Institute of Mental Health 1999). Perhaps these diagnoses are not just a reflection of women’s health, but also a reflection of society’s labeling of female characteristics as pathological, or the result of institutionalized sexism.

Media Attributions

- Figure 12.13 Helping families build a future free from poverty by Find Your Feet, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 12.14 Pink Helmet on Pink and Black Motorcycle by Anastasia Shuraeva is used under the Pexels license.

- Figure 12.15 Female character flowchart by S. Mlawski and Hann Commander, on Overthinking It is used under a CC BY-NC licence.

- Figure 12.16 Emily Murphy, by unknown author at the Provincial Archives of Alberta, via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 12.17 Woman’s work is never done by Evil Erin, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 12.18 [No title. Photo suspected to be from 1960 Better Homes and Gardens, 1960 “Decorating Ideas” issue], uploaded by Ethan, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 12.19 Portrait of Friedrich Engels, by photographer William Hall (1826–ca. 1898), via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 12.20 A trans-masculine gender non-conforming person and transfeminine nonbinary person drinking coffee in bed, by Zackary Drucker, via the The Gender Spectrum Collection. is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 licence .

- Figure 12.21 Female patient with sleep hysteria from Nouvelle iconographie de la Salpêtriêre/Société de neurologie de Paris, 1906-18 in the Wellcome Collection, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY 4.0 licence.